In Silico Identification and Biological Evaluation of Antioxidant Food Components Endowed with Human Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII Inhibition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Molecular Modeling Studies

2.2. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibition Assay

2.3. Inhibition Growth Assay

3. Results

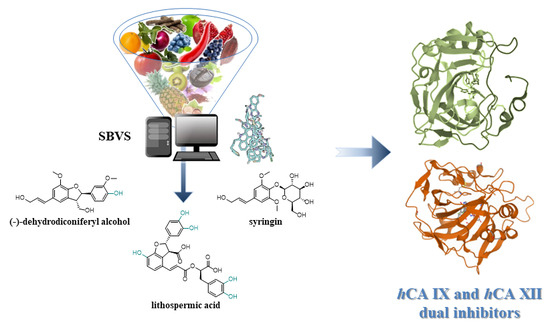

3.1. Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

3.2. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibition Assay

- (i)

- As for compound 14, the data reported in Table 1 clearly showed the tumor-associated hCA XII isoform was 3.5-fold more potently inhibited when compared to the hCA IX (KIs of 0.092 and 0.32 µM, respectively) with a selectivity index (SI; KI hCA IX/KI hCA XII) of 3.5.

- (ii)

- The same kinetic profile was also recovered for 6, although enhanced enzymatic SIs were observed. The tumor-associated hCA XII resulted inhibited 27.0-fold more potently when compared to the IX (KIs of 0.096 and 2.59 µM, respectively).

- (iii)

- Compound 12 was already investigated as a potential inhibitor hCA on the widely expressed hCAs, I and II, and on the tumor-associated IX and XII from some authors of this manuscript and the data reported in Table 1 were in good agreement [28]. It is worth considering that an impressive hCA XII selective inhibition was obtained from such a substance, thus being the most potent and selective against such a tumor-associated isoform (KIs of 0.31 and 0.0048 µM for the hCA IX and XII, respectively).

3.3. Docking Pose and Thermodynamic Analysis of the Best Hits

3.4. Cell Viability Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Supuran, C.T. How many carbonic anhydrase inhibition mechanisms exist? J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboge, M.Y.; McKenna, R.; Frost, S.C. Advances in Anti-Cancer Drug Development Targeting Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII. Top. Anticancer Res. 2015, 5, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T. Exploring the multiple binding modes of inhibitors to carbonic anhydrases for novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug. Discov. 2020, 15, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrases-an overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T. Advances in structure-based drug discovery of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2017, 12, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T.; Scozzafava, A. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2000, 10, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, S.M.; Supuran, C.T.; De Simone, G. Anticancer carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: A patent review (2008–2013). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2013, 23, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboge, M.Y.; Mahon, B.P.; McKenna, R.; Frost, S.C. Carbonic Anhydrases: Role in pH Control and Cancer. Metabolites 2018, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, J.C.; Chiche, J.; Grellier, C.; Lopez, M.; Bornaghi, L.F.; Maresca, A.; Supuran, C.T.; Pouyssegur, J.; Poulsen, S.A. Targeting hypoxic tumor cell viability with carbohydrate-based carbonic anhydrase IX and XII inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6905–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guler, O.O.; De Simone, G.; Supuran, C.T. Drug design studies of the novel antitumor targets carbonic anhydrase IX and XII. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, B.P.; Bhatt, A.; Socorro, L.; Driscoll, J.M.; Okoh, C.; Lomelino, C.L.; Mboge, M.Y.; Kurian, J.J.; Tu, C.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; et al. The Structure of Carbonic Anhydrase IX Is Adapted for Low-pH Catalysis. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 4642–4653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tu, C.; Wang, H.; Silverman, D.N.; Frost, S.C. Catalysis and pH control by membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase IX in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 15789–15796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pacchiano, F.; Carta, F.; McDonald, P.C.; Lou, Y.; Vullo, D.; Scozzafava, A.; Dedhar, S.; Supuran, C.T. Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides potently inhibit carbonic anhydrase IX and show antimetastatic activity in a model of breast cancer metastasis. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1896–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, J.S.; Lin, C.W.; Chuang, C.Y.; Su, S.C.; Lin, S.H.; Yang, S.F. Carbonic anhydrase IX overexpression regulates the migration and progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 9517–9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocentini, A.; Ceruso, M.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T. 7-Aryl-triazolyl-substituted sulfocoumarins are potent, selective inhibitors of the tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase IX and XII. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ozensoy, O.; Puccetti, L.; Fasolis, G.; Arslan, O.; Scozzafava, A.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Inhibition of the tumor-associated isozymes IX and XII with a library of aromatic and heteroaromatic sulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4862–4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.S.; Abou-Seri, S.M.; Tanc, M.; Elaasser, M.M.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A.; Supuran, C.T. Isatin-pyrazole benzenesulfonamide hybrids potently inhibit tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase isoforms IX and XII. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 103, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Supuran, C.T.; Winum, J.Y. Carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors in cancer therapy: An update. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, A.; Beyza Ozturk Sarikaya, S.; Gulcin, I.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of mammalian isoforms I-XIV with a series of natural product polyphenols and phenolic acids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2159–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk Sarikaya, S.B.; Topal, F.; Senturk, M.; Gulcin, I.; Supuran, C.T. In vitro inhibition of alpha-carbonic anhydrase isozymes by some phenolic compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 4259–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scozzafava, A.; Passaponti, M.; Supuran, C.T.; Gulcin, I. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Guaiacol and catechol derivatives effectively inhibit certain human carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes (hCA I, II, IX and XII). J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2015, 30, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagai, H.; Kim, Y.H. Cancer prevention from the perspective of global cancer burden patterns. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.who.int (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Guise, C.P.; Mowday, A.M.; Ashoorzadeh, A.; Yuan, R.; Lin, W.H.; Wu, D.H.; Smaill, J.B.; Patterson, A.V.; Ding, K. Bioreductive prodrugs as cancer therapeutics: Targeting tumor hypoxia. Chin. J. Cancer 2014, 33, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Simone, G.; Vitale, R.M.; Di Fiore, A.; Pedone, C.; Scozzafava, A.; Montero, J.L.; Winum, J.Y.; Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Hypoxia-activatable sulfonamides incorporating disulfide bonds that target the tumor-associated isoform IX. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5544–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rami, M.; Dubois, L.; Parvathaneni, N.K.; Alterio, V.; van Kuijk, S.J.; Monti, S.M.; Lambin, P.; De Simone, G.; Supuran, C.T.; Winum, J.Y. Hypoxia-targeting carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors by a new series of nitroimidazole-sulfonamides/sulfamides/sulfamates. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 8512–8520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karioti, A.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T. An Update on Natural Products with Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitory Activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 1570–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karioti, A.; Ceruso, M.; Carta, F.; Bilia, A.R.; Supuran, C.T. New natural product carbonic anhydrase inhibitors incorporating phenol moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 7219–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Bourne, P.E. Developing multi-target therapeutics to fine-tune the evolutionary dynamics of the cancer ecosystem. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raghavendra, N.M.; Pingili, D.; Kadasi, S.; Mettu, A.; Prasad, S. Dual or multi-targeting inhibitors: The next generation anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1277–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Pollard, J.W. Targeting macrophages: Therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.; Rocca, R.; Juli, G.; Costa, G.; Maruca, A.; Artese, A.; Caracciolo, D.; Tagliaferri, P.; Alcaro, S.; Tassone, P.; et al. A drug repurposing screening reveals a novel epigenetic activity of hydroxychloroquine. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alterio, V.; Di Fiore, A.; D’Ambrosio, K.; Supuran, C.T.; De Simone, G. Multiple binding modes of inhibitors to carbonic anhydrases: How to design specific drugs targeting 15 different isoforms? Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4421–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gidaro, M.C.; Astorino, C.; Petzer, A.; Carradori, S.; Alcaro, F.; Costa, G.; Artese, A.; Rafele, G.; Russo, F.M.; Petzer, J.P.; et al. Kaempferol as Selective Human MAO-A Inhibitor: Analytical Detection in Calabrian Red Wines, Biological and Molecular Modeling Studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruca, A.; Lanzillotta, D.; Rocca, R.; Lupia, A.; Costa, G.; Catalano, R.; Moraca, F.; Gaudio, E.; Ortuso, F.; Artese, A.; et al. Multi-Targeting Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Essential Oils as Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2020, 25, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocca, R.; Moraca, F.; Costa, G.; Talarico, C.; Ortuso, F.; Da Ros, S.; Nicoletto, G.; Sissi, C.; Alcaro, S.; Artese, A. In Silico Identification of Piperidinyl-amine Derivatives as Novel Dual Binders of Oncogene c-myc/c-Kit G-quadruplexes. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, G.; Rocca, R.; Corona, A.; Grandi, N.; Moraca, F.; Romeo, I.; Talarico, C.; Gagliardi, M.G.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Ortuso, F.; et al. Novel natural non-nucleoside inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase identified by shape- and structure-based virtual screening techniques. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 161, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Carta, F.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Artese, A.; Ortuso, F.; Moraca, F.; Rocca, R.; Romeo, I.; Lupia, A.; Maruca, A.; et al. A computer-assisted discovery of novel potential anti-obesity compounds as selective carbonic anhydrase VA inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, R.; Moraca, F.; Costa, G.; Nadai, M.; Scalabrin, M.; Talarico, C.; Distinto, S.; Maccioni, E.; Ortuso, F.; Artese, A.; et al. Identification of G-quadruplex DNA/RNA binders: Structure-based virtual screening and biophysical characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, G.; Rocca, R.; Moraca, F.; Talarico, C.; Romeo, I.; Ortuso, F.; Alcaro, S.; Artese, A. A Comparative Docking Strategy to Identify Polyphenolic Derivatives as Promising Antineoplastic Binders of G-quadruplex DNA c-myc and bcl-2 Sequences. Mol. Inform. 2016, 35, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.; Moraca, F.; Amato, J.; Cristofari, C.; Rigo, R.; Via, L.D.; Rocca, R.; Lupia, A.; Maruca, A.; Costa, G.; et al. Targeting multiple G-quadruplex-forming DNA sequences: Design, biophysical and biological evaluations of indolo-naphthyridine scaffold derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 182, 111627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagetta, D.; Maruca, A.; Lupia, A.; Mesiti, F.; Catalano, R.; Romeo, I.; Moraca, F.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Costa, G.; Artese, A.; et al. Mediterranean products as promising source of multi-target agents in the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 186, 111903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruca, A.; Catalano, R.; Bagetta, D.; Mesiti, F.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Romeo, I.; Moraca, F.; Rocca, R.; Ortuso, F.; Artese, A.; et al. The Mediterranean Diet as source of bioactive compounds with multi-targeting anti-cancer profile. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.foodb.ca (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Leitans, J.; Kazaks, A.; Balode, A.; Ivanova, J.; Zalubovskis, R.; Supuran, C.T.; Tars, K. Efficient Expression and Crystallization System of Cancer-Associated Carbonic Anhydrase Isoform IX. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 9004–9009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smirnov, A.; Manakova, E.; Grazulis, S. Crystal Structure of Human Carbonic Anhydrase Isozyme XII with 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoro-4-(propylthio)benzenesulfonamide; RCSB PDB; 2018. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/5MSA (accessed on 21 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger. Protein Preparation Wizard; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger. Prime; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger. LigPrep; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger. Glide; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadi, F.; Richards, N.G.J.; Guida, W.C.; Liskamp, R.; Lipton, M.; Caufield, C.; Chang, G.; Hendrickson, T.; Still, W.C. MacroModel—An integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. J. Comput. Chem. 1990, 11, 440–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger. MacroModel; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifah, R.G. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop-flow kinetic studies on the native human isoenzymes B and C. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 2561–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Berrino, E.; Angeli, A.; Zhdanov, D.D.; Kiryukhina, A.P.; Milaneschi, A.; De Luca, A.; Bozdag, M.; Carradori, S.; Selleri, S.; Bartolucci, G.; et al. Azidothymidine “Clicked” into 1,2,3-Triazoles: First Report on Carbonic Anhydrase-Telomerase Dual-Hybrid Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 7392–7409. [Google Scholar]

- Angeli, A.; Carta, F.; Donnini, S.; Capperucci, A.; Ferraroni, M.; Tanini, D.; Supuran, C.T. Selenolesterase enzyme activity of carbonic anhydrases. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2020, 56, 4444–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, A.; Mendes, M.; Cabral, C.; Mare, R.; Paolino, D.; Vitorino, C. Hybrid Nanostructured Films for Topical Administration of Simvastatin as Coadjuvant Treatment of Melanoma. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 3396–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger. Maestro Graphics User Interface; Schrödinger LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riafrecha, L.E.; Bua, S.; Supuran, C.T.; Colinas, P.A. Synthesis and carbonic anhydrase inhibitory effects of new N-glycosylsulfonamides incorporating the phenol moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 3892–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Jeong, J.H. A convenient synthesis of an anti-Helicobacter pylori agent, dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2006, 29, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Choi, J.; Choi, H.; Ryu, J.H.; Jeong, J.; Park, E.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S. Dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol isolated from Cucurbita moschata shows anti-adipogenic and anti-lipogenic effects in 3T3-L1 cells and primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 8839–8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 expression by dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol (DHCA) through the AMPK-Nrf2 dependent pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 281, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Ko, K.R.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, D.S.; Nam, I.J.; Lim, S.; Kim, S. Dehydrodiconiferyl Alcohol Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation and Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss through Acting as an Estrogen Receptor Agonist. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Choi, J.; Kim, S. Effective suppression of pro-inflammatory molecules by DHCA via IKK-NF-kappaB pathway, in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 3353–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Cen, Y.; Yang, D.; Qi, Z.; Hou, Z.; Han, S.; Cai, Z.; Liu, K. Bivariate Correlation Analysis of the Chemometric Profiles of Chinese Wild Salvia miltiorrhiza Based on UPLC-Qqq-MS and Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2018, 23, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villalva, M.; Jaime, L.; Aguado, E.; Nieto, J.A.; Reglero, G.; Santoyo, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities from the Basolateral Fraction of Caco-2 Cells Exposed to a Rosmarinic Acid Enriched Extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-Safi, N.-E.; Kollmann, A.; Khlifi, S.; Ducrot, P.-H. Antioxidative effect of compounds isolated from Globularia alypum L. structure–activity relationship. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.S.; Hsu, F.L.; Liu, I.M. Role of sympathetic tone in the loss of syringin-induced plasma glucose lowering action in conscious Wistar rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 445, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| KI (µM) * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Chemical Structure | Hit | hCA I | hCA II | hCA IX | hCA XII |

| 6 | >100 | >100 | 2.59 | 0.096 |

| 12 | >100 [28] | >100 [28] | 0.31 | 0.0048 [28] |

| 14 | >100 | >100 | 0.32 | 0.092 |

| AAZ | 0.250 | 0.012 | 0.026 | 0.0057 | |

| hCA IX | hCA XII | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hit | HB | SB | GC | S | C | HB | SB | GC | S | C |

| 6 | 3 | 0 | 179 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 222 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 8 | 0 | 167 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 291 | 0 | 1 |

| 14 | 3 | 0 | 224 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 222 | 0 | 0 |

| hCA IX | hCA XII | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hit | FooDB ID | ΔE | ΔEElec | ΔEvdW | ΔESolv | ΔE | ΔEElec | ΔEvdW | ΔESolv |

| 6 | FDB021188 | −37.89 | −71.80 | −17.28 | 46.18 | −43.75 | −110.89 | −25.64 | 81.26 |

| 12 | FDB006174 | −23.42 | −59.74 | −12.72 | 37.79 | −31.83 | −227.57 | −28.01 | 206.77 |

| 14 | FDB011657 | −31.22 | −36.62 | −22.44 | 26.06 | −43.81 | −105.69 | −22.33 | 73.05 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, G.; Maruca, A.; Rocca, R.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Berrino, E.; Carta, F.; Mesiti, F.; Salatino, A.; Lanzillotta, D.; Trapasso, F.; et al. In Silico Identification and Biological Evaluation of Antioxidant Food Components Endowed with Human Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII Inhibition. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9090775

Costa G, Maruca A, Rocca R, Ambrosio FA, Berrino E, Carta F, Mesiti F, Salatino A, Lanzillotta D, Trapasso F, et al. In Silico Identification and Biological Evaluation of Antioxidant Food Components Endowed with Human Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII Inhibition. Antioxidants. 2020; 9(9):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9090775

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Giosuè, Annalisa Maruca, Roberta Rocca, Francesca Alessandra Ambrosio, Emanuela Berrino, Fabrizio Carta, Francesco Mesiti, Alessandro Salatino, Delia Lanzillotta, Francesco Trapasso, and et al. 2020. "In Silico Identification and Biological Evaluation of Antioxidant Food Components Endowed with Human Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII Inhibition" Antioxidants 9, no. 9: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9090775