Street Food in Malaysia: What Are the Sodium Levels?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

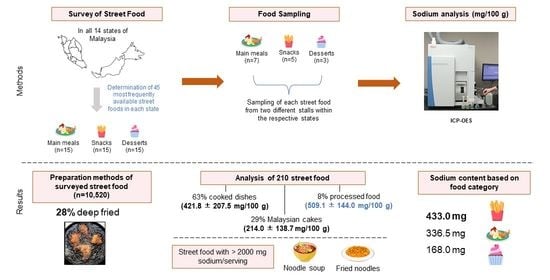

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase I: Survey of Street Foods in All States of Malaysia

2.2. Phase II: Food Sampling

2.2.1. Sampling the Three Categories of Street Food Samples for Each State

2.2.2. Preparation of Street Food Samples for Sodium Analysis

2.2.3. Sodium Content Classification

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- European Commission. Noncommunicable Diseases—NCDs. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/foresight/topic/shifting-health-challenges/non-communicable-diseases-ncds_en (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Institute for Public Health (IPH). Population-Based Salt Intake Survey to Support the National Salt Reduction Programme For Malaysia (Malaysian Community Salt Survey—MyCoSS). Available online: https://iku.moh.gov.my/images/IKU/Document/SALT-FULL_Report.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Public Health (IPH). National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019 (NHMS 2019). Vol. I: Non-Communicable Diseases, Risk Factors & Other Health Problems; Institute for Public Health: Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Seaghdha, C.M.; Perkovic, V.; Lam, T.H.; McGinn, S.; Barzi, F.; Gu, D.F.; Cass, A.; Suh, I.; Muntner, P.; Giles, G.G.; et al. Blood pressure is a major risk factor for renal death: An analysis of participants from the Asia-Pacific region. Hypertension 2009, 54, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donnell, M.J.; Xavier, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Chin, S.L.; Rao-Melacini, P.; Rangarajan, S.; Islam, S.; Pais, P.; McQueen, M.J.; et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): A case-control study. Lancet 2010, 376, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Reducing Salt Intake in Malaysia: An Interim Evaluation of What Works; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steyn, N.P.; McHiza, Z.; Hill, J.; Davids, Y.D.; Venter, I.; Hinrichsen, E.; Opperman, M.; Rumbelow, J.; Jacobs, P. Nutritional contribution of street foods to the diet of people in developing countries: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khongtong, J.; Ab Karim, S.; Othman, M.; Bolong, J. Consumption pattern and consumers’ opinion toward street food in Nakhon Si Thammarat province. Thail. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia, Current Population Estimates, Malaysia 2022. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/pdfPrev&id=dTZXanV6UUdyUEQ0SHNWOVhpSXNMUT09 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Statista 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/455880/urbanization-in-malaysia (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Food & Agriculture Organization. Selling Street and Snack Foods. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i2474e/i2474e.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Tee, E.S.; Isma, M.N.; Nasir, M.A.; Khatijah, I. Nutrient Composition of Malaysian Foods, 4th ed.; Institute for Medical Research: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1997; ISBN 967-99909-8-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier, E.; Chekri, R.; Zinck, J.; Guérin, T.; Noël, L. Simultaneous determination of 31 elements in foodstuffs by ICP-MS after closed-vessel microwave digestion: Method validation based on the accuracy profile. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 41, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide To Creating A Front-Of-Pack Nutrition Label. 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/207588/FINAL_VERSION_OF_THE_2013_FOP_GUIDANCE_-_WEB.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Wong, A.S.C.; Coyle, D.H.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Louie, J.C.Y. Sodium concentration of pre-packaged foods sold in Hong Kong. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2804–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Standards of the People’s Republic of China. Foods with Low-Sodium Content; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of The People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009; 448p. [Google Scholar]

- Njaya, T. Operations of street food vendors and their impact on sustainable urban life in high density suburbs of Harare, in Zimbabwe. Asian J. Econ. Model. 2014, 2, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, F.; Mou, L.T.; Rahmat, S.R.; Gunaratne, M.S. Paddy, rice and food security in Malaysia: A review of climate change impacts. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1818373. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M.; Alamprese, C.; Ratti, S. Tocopherols and tocotrienols as free radical scavengers in refined vegetable oils and their stability during deep-fat frying. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, K.; Tomihe Kunitake, M.; Kazue Aracava, K.; Silvia Favaro Trindade, C. Changes in food caused by deep fat frying—A review. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2013, 63, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tarmizi, S.F.M.; Daud, N.M.; Rahman, H.A. Malaysian ready-to-eat cooked dishes: Consumption patterns among adults and nutrient composition of selected highly consumed dishes. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2020, 49, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, N.; Alistair, T.L.J.; Lim, H.W.; Nopianti, R. Some quality characteristics of Malaysian commercial fish sausage. Pak. J. Nutr. 2012, 11, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haron, H.; Hiew, I.; Shahar, S.; Michael, V.; Ambak, R.A. Survey on salt content labeling of the processed food available in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wan Md. Hatta, W.N.N.M. The Authentic of ‘Keropok lekor’ Process. Arts Des. Stud. 2015, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Murad, N.S.; Ismail, M.A.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R. The effect of mixing time and mixing sequence during processing on the physicochemical and sensory properties of keropok lekor. J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 9, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zim, A.F.M.I.U.; Akter, A.; Ali, M.S.; Anik, W.A.; Ahmed, S.; Zamri, A.I.B. Proximate composition, texture analysis and sensory evaluation of keropok lekor formulated with herbs and spices. Food Res. 2019, 3, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.H.; Man, C.S.; Othman, F.; He, F.J.; Salleh, R.; Noor, N.S.M.; Kozil, W.N.K.W.; MacGregor, G.; Aris, T. High sodium food consumption pattern among Malaysian population. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, S.; You, Y.X.; Zainuddin, N.S.; Michael, V.; Ambak, R.; Haron, H.; He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Sodium content in sauces—A major contributor of sodium intake in Malaysia: A cross-sectional survey. Br. Med. J. Open 2019, 9, e025068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, W.L.; Azlan, A.; Noh, M.F.M. Sodium and potassium contents in selected salts and sauces. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 2181–2186. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C. The psychology of condiments: A review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 11, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Boobyer, C.; Borgonha, Z.; van den Heuvel, E.; Appleton, K.M. Adding flavours: Use of and attitudes towards sauces and seasonings in a sample of community-dwelling UK older adults. Foods 2021, 10, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.G. Asian Noodle Manufacturing: Ingredients, Technology, and Quality; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wieser, H.; Koehler, P.; Scherf, K.A. Wheat-An Exceptional Crop: Botanical Features, Chemistry, Utilization, Nutritional and Health Aspects. Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khor, G.L.; Hsu-Hage, B.H.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Dietary practices in nutritional transition: The case of Malaysian urban Chinese. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1998, 36, 463–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, N.; Li, Y.; Tan, M.; Zhang, P.; He, F.J. Sodium content of restaurant dishes in China: A cross-sectional survey. Nutr. J. 2022, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, A.; Abdullah, N.; Ishak, N. Chemical properties of leftover coconut pulp gluten free flour. Asian J. Arts 2020, 2, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, S.R.; Omar, S.N. Malaysian heritage food (MHF): A review on its unique food culture, tradition and present lifestyle. Int. J. Herit. Art Multimed. 2018, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruzaman, M.Y.B.; Ab Karim, S.; Ishak, F.A.B.C.; Arshad, M.M.B. The diversity of traditional Malay kuih in Malaysia and its potential. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, M.N.A.; Ab Karim, S.; Ishak, F.A.C.; Arshad, M.M. Past and present practices of the Malay food heritage and culture in Malaysia. J. Ethn. Foods 2017, 4, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, M.; Singh, G.; Greer, R.; Cudhea, F.; Matsushita, K.; Micha, R.; Brady, T.; Zhao, D.; Huang, L.; Tian, M.; et al. Estimated population wide benefits and risks in China of lowering sodium through potassium enriched salt substitution: Modeling study. BMJ 2020, 369, m824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions | Coasts | States | Number of Districts Surveyed | Number of Locations Surveyed | Street Foods Category | Total Street Food by States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Meals | Snacks | Desserts | ||||||

| West Malaysia | West Coast | Selangor | 7 | 17 | 792 | 1000 | 553 | 2345 |

| Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur | 7 | 14 | 883 | 935 | 328 | 2146 | ||

| Negeri Sembilan | 1 | 6 | 333 | 305 | 164 | 802 | ||

| Melaka | 1 | 5 | 203 | 480 | 156 | 839 | ||

| Johor | 8 | 194 | 207 | 220 | 143 | 570 | ||

| Kedah | 3 | 11 | 118 | 64 | 35 | 217 | ||

| Perlis | 2 | 8 | 42 | 47 | 20 | 109 | ||

| Perak | 11 | 40 | 90 | 65 | 37 | 192 | ||

| Penang | 4 | 34 | 113 | 44 | 43 | 200 | ||

| East Coast | Terengganu | 7 | 10 | 495 | 504 | 396 | 1395 | |

| Pahang | 8 | 14 | 362 | 356 | 241 | 959 | ||

| Kelantan | 2 | 4 | 92 | 102 | 172 | 366 | ||

| East Malaysia | Not applicable | Sabah | 4 | 8 | 54 | 55 | 28 | 137 |

| Sarawak | 3 | 15 | 103 | 57 | 83 | 243 | ||

| Total | 68 | 380 | 3887 | 4234 | 2399 | 10520 | ||

| Food Category | Percentage (%) | Average Sodium Content (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|---|

| Snacks | 40 | 433.0 ± 198.1 a |

| Main meals | 37 | 336.5 ± 148.2 a |

| Desserts | 23 | 168.0 ± 134.7 b |

| Food Group | Percentage (%) | Average sodium content (mg/100 g) |

| Processed foods | 8 | 509.1 ± 144.0 a |

| Cooked dishes | 63 | 421.8 ± 207.5 a |

| Local cakes | 29 | 214.0 ± 138.7 b |

| No | Name of Street Food (n = Number of States in Which the Street Food Was Sampled) | Street Food Category | mg Sodium/100 g (Mean ± std dev) | mg Sodium/ Serving (Household Measurement) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fried fish ball (n = 3) | Snack | 815.0 ± 47.7 | 1530.9 (6 pieces) |

| 2 | Fried chicken with cheese (n = 1) | Snack | 706.0 ± 24.0 | 1087.2 (1 piece) |

| 3 | Fried crab meatball (n = 2) | Snack | 690.5 ± 18.4 | 553.6 (6 pieces) |

| 4 | Fried sausage (n = 3) | Snack | 690.3 ± 74.4 | 683.4 (3 pieces) |

| 5 | Fried chicken ball (n = 1) | Snack | 605.5 ± 12.0 | 601.3 (6 pieces) |

| 6 | Beef burger (n = 1) | Main meal | 584.0 ± 2.8 | 584.0 (1 piece) |

| 7 | Fried sausage with cheese (n = 1) | Snack | 563.0 ± 9.9 | 802.3 (3 pieces) |

| 8 | Chicken nuggets (n = 5) | Snack | 519.1 ± 73.8 | 327.0 (3 pieces) |

| 9 | Pizza (n = 1) | Snack | 485.0 ± 12.7 | 5432.0 (1 whole regular) |

| 10 | Chicken burger (n = 3) | Main meal | 451.8 ± 102.0 | 682.3 (1 piece) |

| High Sodium Content (>600 mg/100 g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name of Street Food (n = Number of States in Which the Street Food Was Sampled) | Street Food Category | mg Sodium/100 g (Mean ± Std Dev) | mg Sodium/ Serving (Household Measurement) |

| 1 | Fried noodles (n = 10) | Main meal | 704.2 ± 225.4 | 2185.5 (1 plate) |

| 2 | Kolo mee (n = 1) | Main meal | 625.0 ± 1.4 | 1152.5 (1 bowl) |

| Medium Sodium Content (120–599 mg/100 g) | ||||

| No. | Name of Street Food (n = Number of States in Which the Street Food Was Sampled) | Street Food Category | mg Sodium/100 g (Mean ± Std Dev) | mg Sodium/ Serving (Household Measurement) |

| 1 | Bakso (n = 1) | Main meal | 468.5 ± 3.5 | 2576.8 (1 bowl) |

| 2 | Fried kuey teow (n = 7) | Main meal | 437.1 ± 78.6 | 1477.8 (1 plate) |

| 3 | Noodle soup (n = 1) | Main meal | 431.0 ± 29.7 | 2249.8 (1 bowl) |

| 4 | Char kuey teow (n = 2) | Main meal | 418.3 ± 127.6 | 1565.5 (1 plate) |

| 5 | Fried vermicelli @ fried mihun (n = 11) | Main meal | 398.6 ± 133.6 | 797.2 (1 plate) |

| 6 | Soto (n = 1) | Main meal | 377.0 ± 21.2 | 3168.7 (1 bowl) |

| 7 | Fried rice (n = 2) | Main meal | 374.8 ± 38.5 | 749.5 (1 plate) |

| 8 | Vermicelli soup @ mihun sup (n = 3) | Main meal | 360.0 ± 78.8 | 2162.6 (1 bowl) |

| 9 | Nasi lemak with fried chicken (n = 4) | Main meal | 349.1 ± 76.2 | 1431.5 (1 plate) |

| 10 | Nasi tomato (n = 1) | Main meal | 345.5 ± 2.1 | 1935.7 (1 plate) |

| 11 | Noodles with gravy (curry/soy sauce) (n = 4) | Main meal | 336.6 ± 248.4 | 1830.8 (1 bowl) |

| 12 | Nasi lemak (n = 12) | Main meal | 321.7 ± 104.7 | 643.4 (1 plate) |

| 13 | Kuey teow soup (n = 1) | Main meal | 307.0 ± 2.8 | 2076.4 (1 bowl) |

| 14 | Laksa (Penang style) (n = 5) | Main meal | 306.6 ± 93.1 | 1966.6 (1 bowl) |

| 15 | Nasi minyak (n = 2) | Main meal | 304.0 ± 46.0 | 1128.2 (1 plate) |

| 16 | Nasi kerabu (n = 2) | Main meal | 298.5 ± 64.3 | 916.1 (1 plate) |

| 17 | Chicken rice (n = 3) | Main meal | 298.5 ± 25.1 | 746.3 (1 plate) |

| 18 | Laksa (Perak style) (n = 1) | Main meal | 288.0 ± 0.0 | 1789.9 (1 bowl) |

| 19 | Glutinous rice with rendang (meat cooked with spices) (n = 1) | Main meal | 285.5 ± 17.7 | 467.7 (1 set) |

| 20 | Chicken porridge (n = 2) | Main meal | 272.5 ± 0.7 | 452.4 (1 bowl) |

| 21 | Rice porridge (n = 3) | Main meal | 245.5 ± 49.7 | 407.5 (1 bowl) |

| 22 | Glutinous rice with fried fish (n = 1) | Main meal | 216.0 ± 8.5 | 335.1 (1 pack) |

| 23 | Spaghetti bolognese (n = 1) | Main meal | 215.5 ± 13.4 | 1131.4 (1 plate) |

| 24 | Laksam (n = 1) | Main meal | 185.5 ± 0.7 | 519.7 (1 bowl) |

| Street Foods with Medium Sodium Content (120–599 mg/100 g Sample) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name of Street Food (n = Number of States in Which the Street Food Was Sampled) | Street Food Category | mg Sodium/100 g (Mean ± Std Dev) | mg Sodium/Serving (Household Measurement) |

| 1 | Apam balik with cheese (n = 1) | Dessert | 586.5 ± 12.0 | 1343.1 (1 piece) |

| 2 | Kebab (n = 2) | Main meal | 531.5 ± 89.1 | 616.5 (1 piece) |

| 3 | Kerepek (n = 1) | Snack | 512.5 ± 61.5 | 71.8 (1 piece) |

| 4 | Takoyaki (n = 4) | Snack | 502.4 ± 95.3 | 926.0 (6 pieces) |

| 5 | Fried chicken (n = 10) | Snack | 464.9 ± 118.3 | 715.9 (1 piece) |

| 6 | Fried chicken (non-meat parts) (n = 1) | Snack | 461.5 ± 72.8 | 113.1 (4 small pieces) |

| 7 | Roti john (n = 2) | Main meal | 412.0 ± 59.4 | 696.3 (3 pieces) |

| 8 | Satay (n = 2) | Snack | 395.3 ± 177.8 | 296.4 (5 sticks) |

| 9 | Satar (n = 1) | Snack | 390.5 ± 0.7 | 338.3 (3 pieces) |

| 10 | Kuih kacang (n = 1) | Dessert | 384.5 ± 16.3 | 339.9 (3 pieces) |

| 11 | Cakoi (n = 2) | Snack | 376.3 ± 223.1 | 508.4 (3 pieces) |

| 12 | Fried popiah (n = 1) | Snack | 350.0 ± 7.1 | 147.0 (1 piece) |

| 13 | Pulut panggang (n = 1) | Snack | 349.5 ± 3.5 | 174.8 (1 piece) |

| 14 | Putu piring (n = 1) | Dessert | 334.5 ± 57.3 | 184.0 (1 piece) |

| 15 | Kuih bom (n = 1) | Dessert | 327.0 ± 4.2 | 143.9 (1 piece) |

| 16 | Curry puff (n = 8) | Snack | 305.0 ± 87.0 | 146.5 (1 piece) |

| 16 | Banana fritters with cheese (n = 1) | Dessert | 293.0 ± 4.2 | 193.4 (3 pieces) |

| 17 | Murtabak (n = 2) | Snack | 292.3 ± 188.4 | 825.6 (1 piece) |

| 18 | Jering rebus (n = 1) | Snack | 291.5 ± 0.7 | 145.8 (4 pieces) |

| 19 | Kuih seri muka (n = 2) | Dessert | 271.3 ± 73.2 | 260.4 (1 piece) |

| 20 | French fries with sauce (n = 1) | Snack | 262.0 ± 7.1 | 175.5 (1 small serving) |

| 21 | Apam balik telur (n = 1) | Snack | 262.0 ± 2.8 | 600.0 (1 large piece) |

| 22 | Roti canai (flat bread) (n = 2) | Main meal | 262.0 ± 154.9 | 220.1 (1 piece) |

| 23 | Kuih akok (n = 2) | Dessert | 259.3 ± 20.2 | 375.3 (4 pieces) |

| 24 | Donut (n = 4) | Dessert | 254.9 ± 158.1 | 188.6 (1 piece) |

| 25 | Apam balik (n = 4) | Dessert | 253.9 ± 76.1 | 581.4 (1 large piece) |

| 26 | Kuih cara berlauk ayam (n = 1) | Snack | 246.5 ± 3.5 | 310.6 (4 small pieces) |

| 27 | Net crepes (Roti jala) (n = 2) | Main meal | 240.8 ± 1.1 | 584.9 (1 pack) |

| 28 | Kuih tepung gomak (n = 1) | Snack | 235.0 ± 12.7 | 276.7 (4 pieces) |

| 29 | Grilled chicken (small pieces) (n = 1) | Snack | 229.5 ± 4.9 | 581.0 (4 small pieces) |

| 30 | Corn (savory) (n = 2) | Snack | 220.9 ± 242.0 | 1361.3 (1 sheaf) |

| 31 | Egg tart (n = 1) | Dessert | 204.5 ± 9.2 | 242.9 (1 piece) |

| 32 | Kuih puteri ayu (n = 1) | Dessert | 194.0 ± 2.8 | 276.2 (4 pieces) |

| 33 | Banana fritters (n = 4) | Dessert | 160.3 ± 66.8 | 105.8 (3 pieces) |

| 34 | Chee cheong fun (n = 1) | Snack | 146.0 ± 1.4 | 826.0 (1 plate) |

| 35 | Beh hua chee (n = 1) | Snack | 138.5 ± 12.0 | 305.4 (3 pieces) |

| 36 | Kuih sagu (n = 1) | Dessert | 138.0 ± 0.0 | 93.8 (1 piece) |

| 37 | Kuih cek mek molek (n = 1) | Dessert | 125.5 ± 0.7 | 128.9 (4 pieces) |

| 38 | Popcorn (n = 1) | Dessert | 121.5 ± 6.4 | 245.4 (1 container) |

| Street Foods with Low Sodium Content (<120 mg/100 g Sample) | ||||

| No. | Name of Street Food (n = Number of States in Which the Street Food Was Sampled) | Street Food Category | mg Sodium/100 g (Mean ± Std Dev) | mg Sodium/Serving (Household Measurement) |

| 1 | Kuih keria (n = 1) | Dessert | 119.5 ± 2.1 | 37.0 (1 piece) |

| 2 | Cubed rice with peanut gravy (nasi impit) (n = 1) | Main meal | 117.5 ± 0.7 | 58.8 (8 cubes) |

| 3 | Kuih lepat (n = 2) | Dessert | 109.2 ± 44.3 | 126.6 (1 piece) |

| 4 | Kuih calak kuda (n = 1) | Dessert | 104.0 ± 0.0 | 99.8 (4 pieces) |

| 5 | Kuih buah Melaka (n = 1) | Dessert | 89.9 ± 0.6 | 13.5 (1 piece) |

| 6 | Kuih lapis (n = 2) | Dessert | 89.6 ± 93.9 | 89.6 (1 piece) |

| 7 | Cekodok (n = 1) | Dessert | 84.7 ± 33.0 | 25.4 (3 pieces) |

| 8 | Steamed baozi with sweet fillings (n = 2) | Dessert | 69.1 ± 27.5 | 34.6 (1 piece) |

| 9 | Peneram (n = 1) | Dessert | 59.1 ± 1.6 | 18.9 (5 small pieces) |

| 10 | Cendol (n = 2) | Dessert | 56.9 ± 2.8 | 431.7 (1 bowl) |

| 11 | Kuih apam (n = 1) | Dessert | 56.1 ± 1.3 | 22.4 (3 pieces) |

| 12 | Kuih jelurut (n = 1) | Dessert | 49.8 ± 2.1 | 101.6 (4 pieces) |

| 13 | Tau fu fa (n = 1) | Dessert | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 23.6 (1 container) |

| 14 | Kuih penjaram (n = 1) | Dessert | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 9.1 (4 pieces) |

| 15 | Kuih angku (n = 1) | Dessert | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 14.1 (4 pieces) |

| 16 | Putu (n = 1) | Main meal | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 7.2 (1 piece) |

| 17 | Sianglag (n = 1) | Main meal | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.9 (1 pack) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haron, H.; Zainal Arifen, Z.N.; Shahar, S.; Mohamad, H.; Mohd Yazid, S.F.Z.; Michael, V.; Abeyasinghe, R.; Taketo, T.; Trieu, K. Street Food in Malaysia: What Are the Sodium Levels? Foods 2022, 11, 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11233791

Haron H, Zainal Arifen ZN, Shahar S, Mohamad H, Mohd Yazid SFZ, Michael V, Abeyasinghe R, Taketo T, Trieu K. Street Food in Malaysia: What Are the Sodium Levels? Foods. 2022; 11(23):3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11233791

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaron, Hasnah, Zainorain Natasha Zainal Arifen, Suzana Shahar, Hamdan Mohamad, Siti Farrah Zaidah Mohd Yazid, Viola Michael, Rabindra Abeyasinghe, Tanaka Taketo, and Kathy Trieu. 2022. "Street Food in Malaysia: What Are the Sodium Levels?" Foods 11, no. 23: 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11233791