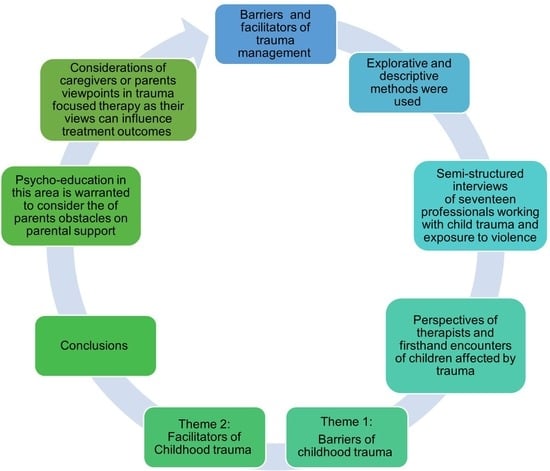

Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators in the Management of Childhood Trauma and Violence Exposure Intervention in the Vhembe District of the Limpopo Province, South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

- The aim of the study was to explore and describe the barriers and facilitators to managing childhood trauma and exposure to violence in the Vhembe district.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Population, Recruitment, and Sampling Data Collection

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Sample Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Patient-Based Barriers

3.1.1. Fear of Perpetrators

“Wa tseba ge e le bana ba bannyane [You know when it comes to young children] for them to go and report or tell someone in the family, …that maybe it’s your sister, my sister is abusing me, they are scared of them, of those people because they know that they will beat them when they get home and ask why did you tell those people that I beat you or I don’t give you food”(P1)

3.1.2. Reluctant to Consult

“This client was raped for some time, and she revealed this to a friend, and the friend informed the teacher, the teacher informed the parent, and she was brought here; when she got here, she said no, I need no help, and the only person who needs help is my mom, but I could see gore [that] the child needs help, but then the child says I don’t”(P4)

3.1.3. Financial Challenges

“In my experience, they default due to financial issues, or due to…, maybe they have been moved to another area”(P14)

“Majority of our people are struggling; they do not have money to come for their treatment, so that’s the challenge we are facing”(P3)

3.1.4. Unsupportive Parents

“I would say sometimes it’s the commitment of parents. Some parents do not prioritise the child, so they bring it once. When they are supposed to get them for follow-up, the parent is out of town or cannot find anyone to bring the child or things like that. Another one would be if parents are separated. Sometimes, the child is with another parent, and the parent does not take matters to... It’s mostly parents”(P11)

“Parents are not YOH!’’ (frustrated) compliant, especially after the first and second appointments; remember now that we will be doing the first session. After that, we will inform the parents that we will do feedback sessions and explain the assessment’s meaning. They would change guardians, miss appointments and make excuses”(P9)

3.1.5. Unsupportive Work and School Regulations

“Also, parents of the children experiencing trauma would also experience challenges of getting leave of absence from work to bring children to attend psychotherapy sessions, and schools are making it difficult for children to come for follow-up sessions. Just adding on that, working parents getting time off from work is a bit difficult. If it’s a school going child, the school doesn’t want the child to be absent from school or even leave early. So, follow-up is a serious problem”(P10).

3.2. Healthcare Provider Barriers

3.2.1. Professional Boundaries

“…because if you check the case, if you check the incident… The incident happened for some time, she was raped multiple times, so when she came in, she said no, I need no help, I think, she said no, she didn’t, she said I’m ok, I don’t need help, but according to the law I’m not allowed to force her. If she said no, …”(P4)

3.2.2. Delays in Referral Route

“Cases are received from the district and referred to our supervisors, who allocate them to us. The courts will expect the victim impact report and give us only two weeks to conclude the report, which is not enough time. In most cases, you might find that we only interviewed the child once and did not gather enough information”(P15).

“With those ones ‘eish’ (frustrated), the child protection unit would refer the child to our offices. You will find that I am working on a victim impact report of a child that was raped 10 years ago. You will find that a child has already forgotten or was coping, but now you will be reminding that child about something that they forgot or have found a way to cope with it, and during the interview they become emotional”(P17)

3.2.3. Inadequate Education on Case Management and Referral

“Firstly, referrals. Most referrals go to SAPS, where I think there might be challenges because, at times, they do not refer the cases to relevant professionals. Only after the second incident do we become aware of the first occurrence. There is a need for more education not only for communities but also for different departments involved”(P16).

3.3. Facilitators in Managing Childhood Trauma and Violence

3.3.1. Continuous Training and Workshops for Healthcare Workers Working with Childhood Trauma and Exposure to Violence

“Uhmm… (long pause). No, I haven’t had training like a specific course related to trauma; I think because I am a Clinical psychologist and the scope of practice that was covered during the time of studying and internship”(P9)

“I remember in 2019, …before the COVID and stuff. I attended this other workshop, which focused on, you know…children overcoming trauma, but that was in 2019. Since then, I haven’t been to any other training except the one I went to recently, which was about, what was it about, hmm…, child offenders. That is the one I attended last year”(P14)

3.3.2. Employment of More Victim Advocates

“We need more people to be employed as victim advocates, and these people will improve the lives of many victims”(P2)

“No, except for the victim advocate to just call the family if the child is gone back home, she must call them and ask if the child is ok. So, victim advocates must be employed in all centres”(P1)

3.3.3. Awareness Campaigns

“We can conduct campaigns to share the information with those people because sometimes you may find that what this client has experienced, there are some learners who are experiencing the same thing”(P4)

“We do campaigns for prevention and care and provide support in the community, informing the community about what to do when the child experiences trauma and how to report it. With care, …will be regarding providing a safe space for the child away from the perpetrators to ensure that they are not alone. We are there for them”(P15)

4. Discussions

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Preventing Violence against Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Unicef 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2023 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Makongoza, M.; Kiguwa, P.; Mayisela, S. Intimate Partner Violence in Cohabiting Relationships: Young Women’s Voices from Rural Vhembe District, South Africa. In Cohabitation and the Evolving Nature of Intimate and Family Relationships; Emerald Publishing Limited: England, UK, 2023; Volume 24, pp. 211–235. [Google Scholar]

- Rikhotso, R.; Netangaheni, T.R.; Mhlanga, N.L. Psychosocial effects of gender-based violence among women in Vhembe district: A qualitative study. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2023, 29, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vhembe District Municipality; 2019/20 IDP Review; StatsSA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019.

- South African Police Service Crime Statistics. Crime Research and Statistics. 2012. Available online: http://www.saps.gov.za/statistics/reports/crimestats/2012/categories/total_sexual_offences.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Tsheole, P.; Makhado, L.; Maphula, A. Childhood trauma and exposure to violence interventions: The need for effective and feasible evidence-based interventions. Children 2023, 10, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsheole, P.; Makhado, L.; Maphula, A.; Sepeng, N.V. Development and validation of an intervention for childhood trauma and exposure to violence in Vhembe District, South Africa. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, L.; Fanslow, J.; Gulliver, P.; McIntosh, T. Intergenerational impact of violence exposure: Emotional-behavioural and school difficulties in children aged 5–17. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 771834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziv, Y.; Kupermintz, H. The effects of exposure to political and domestic violence on preschool children and their mothers. Int. J. Psychol. 2019, 56, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asagba, R.; Noibi, O.; Ogueji, I. Gender differences in children’s exposure to domestic violence in Nigeria. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2021, 15, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rensburg, A.J.; Myburgh, C.; Szabo, C.; Poggenpoel, M. The role of spirituality in specialist psychiatry: A review of the medical literature. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2013, 16, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A.W.; Bystritsky, A.; Russo, J.E.; Craske, M.G.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Stein, M.B.; Roy-Byrne, P.P. Beliefs about psychotropic medication and psychotherapy among primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2005, 21, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandl, E.J.; Dietrich, N.; Mell, N.; Winkler, J.G.; Gutwinski, S.; Bretz, H.J.; Schouler-Ocak, M. Attitudes towards psychopharmacology and psychotherapy in psychiatric patients with and without migration background. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugmore, N. The development of psychoanalytic parent–infant/child psychotherapy in South Africa: Adaptive responses to contextual challenges. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2012, 24, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugmore, N. The development of parent-infant/child psychotherapy in South Africa: A review of the history from infancy towards maturity. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2011, 23, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nöthling, J.; Suliman, S.; Martin, L.; Simmons, C.; Seedat, S. Differences in abuse, neglect, and exposure to community violence in adolescents with and without PTSD and depression. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 34, 4357–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bain, K. “New Beginnings” in South African shelters for the homeless: Piloting of a group psychotherapy intervention for high-risk mother–infant dyads. Infant Ment. Health J. 2014, 35, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Chen, P.; Zhou, H.; Ruan, J.; Chen, D.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y. The effect of childhood trauma on suicide risk: The chain mediating effects of resilience and mental distress. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yin, Y.; Cui, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Yao, Y. The mediating and moderating effects of resilience between childhood trauma and geriatric depressive symptoms among Chinese community-dwelling older adults. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1137600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasinghe, D. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) as a coaching research methodology. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, D.; Hanlon, C.; Fekadu, A.; Tekola, B.; Baheretibeb, Y.; Hoekstra, R.A. Stigma, explanatory models, and unmet needs of caregivers of children with developmental disorders in a low-income African country: A cross-sectional facility-based survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, S.; Bockstal-Fieulaine, B.; Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Besche-Richard, C.; Boujut, E.; Johnson Harrison, A.; Cappe, E. Evaluation of an Autism Training in a Much-Needed Context: The Case of France. Autism Adulthood 2023, 5, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautrin, J. Rapport sur le Vécu Des Autistes et de Leurs Familles en France à L’aube du XXIème Siècle; Éditions Autisme: Limoges, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rajcumar, N.R.; Paruk, S. Knowledge and misconceptions of parents of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder at a hospital in South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2020, 62, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosreis, S.; Zito, J.M.; Safer, D.J.; Soeken, K.L.; Mitchell, J.W.; Ellwood, L.C. Parental perceptions and satisfaction with stimulant medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2003, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.; Lambert, H. Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: Mechanisms of risk and resilience. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 14, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freyd, J.; DePrince, A.; Gleaves, D. The state of betrayal trauma theory: Reply to mcnally—Conceptual issues, and future directions. Memory 2007, 15, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, C.; Field, N. Unspoken: Child-perpetrator dynamic in the context of intrafamilial child sexual abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP3585–NP3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Bisson, J.B.; Saade, S.; Obeid, R.; Kofner, B.; Harrison, A.J.; Daou, N.; Tricarico, N.; Santos, J.D.; Pinkava, W.; et al. If you want to develop an effective autism training, ask autistic students to help you. Autism 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Brooks, P.J.; Someki, F.; Obeid, R.; Shane-Simpson, C.; Kapp, S.K.; Daou, N.; Smith, D.S. Changing college students’ conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2553–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.J.; Long, K.A.; Manji, K.P.; Blane, K.K. Development of a brief intervention to improve knowledge of autism and behavioral strategies among parents in Tanzania. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 54, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Daou, N.; Sanchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Kapp, S.K.; Obeid, R.; Brooks, P.J.; Someki, F.; Silton, N.; Abi-Habib, R. Factors underlying cross-cultural differences in stigma toward autism among college students in Lebanon and the United States. Autism 2019, 23, 1993–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, D.; Hanlon, C.; Araya, M.; Davey, B.; Hoekstra, R.A.; Fekadu, A. Training needs and perspectives of community health workers in relation to integrating child mental health care into primary health care in a rural setting in sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Autism Spectrum Disorders & Other Developmental Disorders from Raising Awareness to Building Capacity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Obeid, R.; Saade, S. An urgent call for action: Lebanon’s children are falling through the cracks after economic collapse and a destructive blast. Glob. Ment. Health 2022, 9, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsheole, P.; Makhado, L.; Maphula, A.; Sepeng, N.V. Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators in the Management of Childhood Trauma and Violence Exposure Intervention in the Vhembe District of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Children 2024, 11, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050516

Tsheole P, Makhado L, Maphula A, Sepeng NV. Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators in the Management of Childhood Trauma and Violence Exposure Intervention in the Vhembe District of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Children. 2024; 11(5):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050516

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsheole, Petunia, Lufuno Makhado, Angelina Maphula, and Nombulelo Veronica Sepeng. 2024. "Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators in the Management of Childhood Trauma and Violence Exposure Intervention in the Vhembe District of the Limpopo Province, South Africa" Children 11, no. 5: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050516