Bridging Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Potential Role for Ketogenesis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

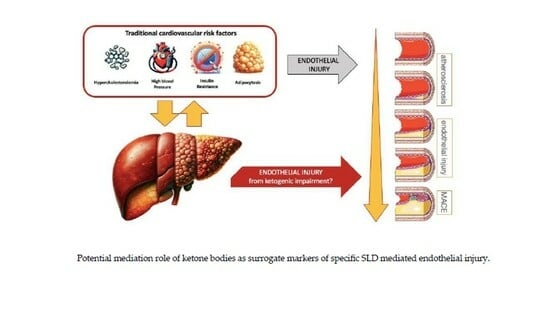

2. Liver Steatotic Disease as a Potential Residual Cardiovascular Risk Factor

3. Metabolic Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Role in Ketogenesis Impairment

3.1. Ketogenesis Impairment in MASLD

3.2. Ketogenesis Impairment in Cardiovascular Disease

3.3. Impaired Ketogenesis: Bridging Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, E153–E639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmis, A.; Vardas, P.; Townsend, N.; Torbica, A.; Katus, H.; De Smedt, D.; Gale, C.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Petersen, S.E.; Huculeci, R.; et al. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 716–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2013–2020 Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2013. Available online: www.who.int (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N.B.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Black, T.; Brewer, L.C.; Foraker, R.E.; Grandner, M.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Marma Perak, A.; Sharma, G.; et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, E18–E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaye, B.; Tafflet, M.; Arveiler, D.; Montaye, M.; Wagner, A.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Ke, F.; Evans, A.; Amouyel, P.; Ferrieres, J.; et al. Ideal Cardiovascular Health and Incident Cardiovascular Disease: Heterogeneity across Event Subtypes and Mediating Effect of Blood Biomarkers: The PRIME Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthakis, V.; Enserro, D.M.; Murabito, J.M.; Polak, J.F.; Wollert, K.C.; Januzzi, J.L.; Wang, T.J.; Tofler, G.; Vasan, R. Ideal cardiovascular health: Associations with biomarkers and subclinical disease and impact on incidence of cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation 2014, 130, 1676–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, T.S.; Ning, H.; Daviglus, M.L.; Liu, K.; Burke, G.L.; Cushman, M.; Eng, J.; Folsom, A.R.; Lutsey, P.L.; Nettleton, J.A.; et al. Association of Cardiovascular Health with Subclinical Disease and Incident Events: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottinger, T.D.; Khan, S.S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tindle, H.A.; Allison, M.; Wells, G.; Shadyab, A.H.; Nassir, R.; Warsinger Martin, L.; et al. Association of cardiovascular health and epigenetic age acceleration. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, B.T.; Gao, T.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Hwang, S.J.; Liu, L.; Nannini, D.; Horvath, S.; Lu, A.T.; Bai Allen, N.; et al. Epigenetic Age Acceleration Reflects Long-Term Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2021, 129, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnussen, C.; Ojeda, F.M.; Leong, D.P.; Alegre-Diaz, J.; Amouyel, P.; Aviles-Santa, L.; De Bacquer, D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A.; Bobak, M.; et al. Global Impact of Modifiable Risk Factors on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hegele, R.A.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Chapman, M.J.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Kuivenhoven, J.A.; Averna, M.; Borén, J.; Bruckert, E.; Catapano, A.L.; Descamps, O.S.; et al. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: Implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, U.; Parhofer, K.G.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Hegele, R.A. Clinical review on triglycerides. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, V.; Aguiar, C.; Alsayed, N.; Chibber, Y.S.; Elbadawi, H.; Ezhov, M.; Hermans, M.P.; Chandra Pandey, R.; Ray, K.K.; Tokgözoglu, L.; et al. Non-HDL-cholesterol in dyslipidemia: Review of the state-of-the-art literature and outlook. Atherosclerosis 2023, 383, 117312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willeit, P.; Yeang, C.; Moriarty, P.M.; Tschiderer, L.; Varvel, S.A.; McConnell, J.P.; Tsimikas, S. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Corrected for Lipoprotein(a) Cholesterol, Risk Thresholds, and Cardiovascular Events. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, 16318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinder, M.; DeCastro, M.L.; Azizi, H.; Cermakova, L.; Jackson, L.M.; Frohlich, J.; John Mancini, G.B.; Francis, G.A.; Brunham, L.R. Ascertainment Bias in the Association between Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2682–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsted, A.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Benn, M.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. High lipoprotein(a) as a possible cause of clinical familial hypercholesterolaemia: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis—An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, D.I.; Holmes, M.V.; Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Engmann, J.E.L.; Shah, T.; Sofat, R.; Guo, Y.; Chung, C.; Peasey, A.; Pfister, T.; et al. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: A mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet 2012, 379, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Ridker, P.M.; Hennekens, C.H.; Buring, J.E.; Rifai, N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Angelopoulos, A.; Papanikolaou, P.; Simantiris, S.; Oikonomou, E.K.; Vamvakaris, K.; Koumpoura, A.; Farmaki, M.; Trivella, M.; Vlachopoulos, C.; et al. Biomarkers of Vascular Inflammation for Cardiovascular Risk Prognostication: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2022, 15, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniades, C.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Deanfield, J. Imaging Residual Inflammatory Cardiovascular Risk. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/6/748/5533079 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Figueroa, A.L.; Abdelbaky, A.; Truong, Q.A.; Corsini, E.; MacNabb, M.H.; Lavender, Z.R.; Lawler, M.A.; Grinspoon, S.K.; Brady, T.J.; Nasir, K.; et al. Measurement of Arterial Activity on Routine FDG PET/CT Images Improves Prediction of Risk of Future CV Events. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, B.; Fernández-Ortiz, A.; Fernández-Friera, L.; García-Lunar, I.; Andrés, V.; Fuster, V. Progression of Early Subclinical Atherosclerosis (PESA) Study: JACC Focus Seminar 7/8. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Friera, L.; Fuster, V.; López-Melgar, B.; Oliva, B.; Sánchez-González, J.; Macías, A.; Pérez-Asenjo, B.; Zamudio, D.; Alonso-Farto, J.C.; España, S.; et al. Vascular Inflammation in Subclinical Atherosclerosis Detected by Hybrid PET/MRI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Urbistondo, D.; Beltrán, A.; Beloqui, O.; Huerta, A. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of systemic endothelial dysfunction in asymptomatic subjects. Nefrologia 2016, 36, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, P.B.; Welty, F.K.; Miller, M.; Chait, A.; Hammond, G.; Ahmad, Z.; Cohen, D.E.; Horton, J.D.; Pressman, G.S.; Toth, P.P.; et al. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, e168–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.; Tacke, F.; Arrese, M.; Chander Sharma, B.; Mostafa, I.; Bugianesi, E.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Yilmaz, Y.; George, J.; Fan, J.; et al. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019, 69, 2672–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.; Anstee, Q.M.; Marietti, M.; Hardy, T.; Henry, L.; Eslam, M.; George, J.; Bugianesi, E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Nexus of Metabolic and Hepatic Diseases. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: Integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Liu, Z.X.; Qu, X.; Elder, B.D.; Bilz, S.; Befroy, D.; Romanelli, A.J.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32345–32353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, A.; Beddow, S.A.; Geisler, J.G.; Kahn, M.; Zhang, X.-m.; Monia, B.P.; Bhanot, S.; Shulman, G.I. Inhibition of protein kinase Cepsilon prevents hepatic insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.T.; Corey, K.E.; Chung, R.T.; Loomba, R.; Benjamin, E.J. Hepatic Fibrosis Associates with Multiple Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors: The Framingham Heart Study. Hepatology 2021, 73, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo, S.; Carbone, M.; Invernizzi, P.; Perseghin, G. Exploring the landscape of steatotic liver disease in the general US population. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 2425–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.D.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Somers, V.; Kim, S.U.; Chahal, C.A.A.; Wong, V.W.; Cai, J.; Shapiro, M.D.; Eslam, M.; et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on MAFLD and the risk of CVD. Hepatol. Int. 2023, 17, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.L.; Tavaglione, F.; Romeo, S.; Charlton, M. Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo, S.; Cannistraci, R.; Mazzetti, S.; Mortara, A.; Perseghin, G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Liver Fibrosis and Cardiovascular Disease in the Adult US Population. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 711484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Loomis, A.K.; Van Der Lei, J.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Ansell, D.; Pasqua, A.; Lapi, F.; Rijnbeek, P.; Mosseveld, M.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident acute myocardial infarction and stroke: Findings from matched cohort study of 18 million European adults. BMJ 2019, 367, l5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.G.; Roelstraete, B.; Hagström, H.; Sundström, J.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and incident major adverse cardiovascular events: Results from a nationwide histology cohort. Gut 2022, 71, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Simons, P.I.H.G.; Wesselius, A.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Brouwers, M.C.G.J. Relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease: A Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology 2023, 77, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, G.; Day, C.P.; Dufour, J.F.; Canbay, A.; Nobili, V.; Ratziu, V.; Tilg, H.; Roden, M.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; et al. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, G.; Enea, M.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Viganò, M.; Bugianesi, E.; Wong, V.W.S.; Fracanzani, A.L.; Sebastiani, G.; Boursier, J.; Berzigotti, A.; et al. Liver-related and extrahepatic events in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A retrospective competing risks analysis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castera, L.; Friedrich-Rust, M.; Loomba, R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1264–1281.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Diaz-Del-Campo, N.; Martínez-Urbistondo, D.; Bugianesi, E.; Martínez, J.A. Diagnostic scores and scales for appraising Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and omics perspectives for precision medicine. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2022, 25, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urbistondo, D.; del Villar, R.S.; Argemí, J.; Daimiel, L.; Ramos-López, O.; San-Cristobal, R.; Villares, P.; Martinez, J.A. Antioxidant Lifestyle, Co-Morbidities and Quality of Life Empowerment Concerning Liver Fibrosis. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Urbistondo, D.; San Cristóbal, R.; Villares, P.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Babio, N.; Corella, D.; del Val, J.L.; Ordovás, J.M.; Alonso-Gómez, A.M.; Wärnberg, J.; et al. Role of NAFLD on the Health Related QoL Response to Lifestyle in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: The PREDIMED Plus Cohort. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 868795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urbistondo, D.; Huerta, A.; Navarro-González, D.; Sánchez-Iñigo, L.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Landecho, M.F.; Martinez, J.A.; Pastrana-Delgado, J.C. Estimation of fatty liver disease clinical role on glucose metabolic remodelling phenotypes and T2DM onset. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e14036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urbistondo, D.; D’Avola, D.; Navarro-González, D.; Sanchez-Iñigo, L.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Perez-Diaz-del-Campo, N.; Bugianesi, E.; Martinez, J.A.; Pastrana, J.C. Interactive Role of Surrogate Liver Fibrosis Assessment and Insulin Resistance on the Incidence of Major Cardiovascular Events. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Csermely, A.; Petracca, G.; Beatrice, G.; Corey, K.E.; Simon, T.G.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Byrne, C.D.; Bonora, E.; Targher, G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Risk of Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, M.; Younossi, Z.M. Independent association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease in the US population. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haring, R.; Wallaschofski, H.; Nauck, M.; Dörr, M.; Baumeister, S.E.; Völzke, H. Ultrasonographic hepatic steatosis increases prediction of mortality risk from elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Choi, S.Y.; Park, E.H.; Lee, W.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, W.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, J.-H.; Jeong, S.-H.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with coronary artery calcification. Hepatology 2012, 56, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Bertolini, L.; Padovani, R.; Rodella, S.; Tessari, R.; Zenari, L.; Day, C.; Arcaro, G. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, T.; Eslam, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Yamamura, S.; Kawaguchi, A.; Nakano, D.; Koseki, M.; Yoshinaga, S.; Takahashi, H.; Anzai, K.; et al. MAFLD better predicts the progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk than NAFLD: Generalized estimating equation approach. Hepatol. Res. 2021, 51, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, M.; Kojima, T.; Takeda, N.; Nagata, C.; Takeda, J.; Sarui, H.; Kawahito, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Suetsugu, A.; Kato, T.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a novel predictor of cardiovascular disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitaka, H.; Hamaguchi, M.; Kojima, T.; Fukuda, T.; Ohbora, A.; Fukui, M. Nonoverweight nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and incident cardiovascular disease: A post hoc analysis of a cohort study. Medicine 2017, 96, e6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.S.; Wong, G.L.H.; Yip, G.W.K.; Lo, A.O.S.; Limquiaco, J.; Chu, W.C.W.; Chim, A.M.-L.; Yu, C.M.; Yu, J.; Chan, F.K.-L.; et al. Coronary artery disease and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2011, 60, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.D.; Nasir, K.; Conceição, R.D.; Sarwar, A.; Carvalho, J.A.M.; Blumenthal, R.S. Hepatic steatosis is associated with a greater prevalence of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic men. Atherosclerosis 2007, 194, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Mingolla, L.; Rigolon, R.; Pichiri, I.; Cavalieri, V.; Zoppini, G.; Lippi, G.; Bonora, E.; Targher, G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in adult patients with type 1 diabetes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 225, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfood Haddad, T.; Hamdeh, S.; Kanmanthareddy, A.; Alla, V.M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the risk of clinical cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2017, 11 (Suppl. S1), S209–S216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhou, X.D.; Wu, S.J.; Hu, X.Q.; Tang, B.; Van Poucke, S.; Pan, X.Y.; Wu, W.J.; Gu, X.M.; Fu, S.W.; et al. Synergistic increase in cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 30, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinger, J.L.; Pencina, K.M.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Seshadri, S.; Fox, C.S.; O´Donnell, C.J.; Speliotes, E.K. Hepatic steatosis and cardiovascular disease outcomes: An analysis of the Framingham Heart Study. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assy, N.; Djibre, A.; Farah, R.; Grosovski, M.; Marmor, A. Presence of coronary plaques in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Radiology 2010, 254, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Nien, C.K.; Yang, C.C.; Yeh, Y.H. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery calcification. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Koo, B.K.; Kim, W.; Kim, W.H. Histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Hepatol. Int. 2021, 15, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstedt, M.; Hagström, H.; Nasr, P.; Fredrikson, M.; Stål, P.; Kechagias, S.; Hultcrantz, R. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.S.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, B.K.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease identifies subjects with cardiovascular risk better than non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, R.; Giral, P.; Khan, J.F.; Rosenbaum, D.; Housset, C.; Poynard, T.; Ratziu, V.; LIDO Study Group. Fatty liver is an independent predictor of early carotid atherosclerosis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, E.H.; Lee, M.J.; Bae, I.Y.; Jung, C.H.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, W.J. Association between noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis and coronary artery calcification progression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, G.; Di Marco, V.; Buscemi, C.; Mazzola, G.; Randazzo, C.; Spatola, F.; Craxi, A.; Buscemi, S.; Petta, S. Interplay between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk in an asymptomatic general population. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 2389–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooli, R.G.R.; Ramakrishnan, S.K. Emerging Role of Hepatic Ketogenesis in Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 946474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, E.; Chevli, P.A.; Islam, T.; German, C.A.; Otvos, J.; Yeboah, J.; Rodriguez, F.; deFilippi, C.; Lima, J.A.C.; Blaha, M.; et al. Circulating ketone bodies and cardiovascular outcomes: The MESA study. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.; Møller, N.; Gormsen, L.C.; Tolbod, L.P.; Hansson, N.H.; Sorensen, J.; Harms, H.J.; Frokiaer, J.; Eiskjaer, H.; Jespersen, N.R.; et al. Cardiovascular Effects of Treatment with the Ketone Body 3-Hydroxybutyrate in Chronic Heart Failure Patients. Circulation 2019, 139, 2129–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.R.; Kim, D.H.; Park, M.H.; Lee, B.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, E.K.; Chung, K.W.; Kim, S.M.; Im, D.S.; Chung, H.Y. β-Hydroxybutyrate suppresses inflammasome formation by ameliorating endoplasmic reticulum stress via AMPK activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66444–66454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, D.G.; Schugar, R.C.; Crawford, P.A. Ketone body metabolism and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 304, H1060–H1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalska, P.; Crawford, P.A. Multi-dimensional Roles of Ketone Bodies in Fuel Metabolism, Signaling, and Therapeutics. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koliaki, C.; Roden, M. Hepatic energy metabolism in human diabetes mellitus, obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2013, 379, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, D.G.; Ercal, B.; Huang, X.; Leid, J.M.; D’Avignon, D.A.; Graham, M.J.; Dietzen, D.J.; Brunt, E.M.; Patti, G.J.; Crawford, P.A. Ketogenesis prevents diet-induced fatty liver injury and hyperglycemia. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 5175–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunny, N.E.; Parks, E.J.; Browning, J.D.; Burgess, S.C. Excessive hepatic mitochondrial TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis in humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Fletcher, J.A.; Deja, S.; Inigo-Vollmer, M.; Burgess, S.C.; Browning, J.D. Persistent fasting lipogenesis links impaired ketogenesis with citrate synthesis in humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e167442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoiswohl, G.; Stefanovic-Racic, M.; Menke, M.N.; Wills, R.C.; Surlow, B.A.; Basantani, M.K.; Sitnick, M.T.; Cai, L.; Yazbeck, C.F.; Stolz, D.B.; et al. Impact of reduced ATGL-mediated adipocyte lipolysis on obesity-associated insulin resistance and inflammation in male mice. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 3610–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begriche, K.; Igoudjil, A.; Pessayre, D.; Fromenty, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH: Causes, consequences and possible means to prevent it. Mitochondrion 2006, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, F.; Gastaldelli, A.; Svegliati Baroni, G.; Tell, G.; Tiribelli, C. Molecular basis and mechanisms of progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Trends Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Lefebvre, P.; Staels, B. Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, M.; Shu, X.; Guo, B.; Jia, T.; Feng, J.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Cardiac Metabolism, Reprogramming, and Diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2023, 17, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, T.R.; Puchalska, P.; Crawford, P.A.; Kelly, D.P. Ketones and the Heart: Metabolic Principles and Therapeutic Implications. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 882–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. Critical Reanalysis of the Mechanisms Underlying the Cardiorenal Benefits of SGLT2 Inhibitors and Reaffirmation of the Nutrient Deprivation Signaling/Autophagy Hypothesis. Circulation 2022, 146, 1383–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Delgado, A.P.; Arteaga Herrera, E.; Tumbaco Mite, C.; Delgado Cedeno, P.; Van Loon, M.C.; Badimon, J.J. Renal and Cardiovascular Metabolic Impact Caused by Ketogenesis of the SGLT2 Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolwicz, S.C. Ketone Body Metabolism in the Ischemic Heart. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 789458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanikarla-Marie, P.; Jain, S.K. Hyperketonemia and ketosis increase the risk of complications in type 1 diabetes. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 95, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterhoff, J.; Tian, R. Metabolic mechanisms in physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: New paradigms and challenges. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 812–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, T.; Hirschey, M.D.; Newman, J.; He, W.; Shirakawa, K.; Le Moan, N.; Grueter, C.A.; Lim, H.; Saunders, L.R.; Stevens, R.D.; et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science 2013, 339, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, A.; Garcia, E.; van den Berg, E.H.; Flores-Guerrero, J.L.; Gruppen, E.G.; Groothof, D.; Westenbrink, B.D.; Connelly, M.A.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Dullart, R.P.F. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, circulating ketone bodies and all-cause mortality in a general population-based cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggini, M.; Morelli, M.; Buzzigoli, E.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Bugianesi, E.; Gastaldelli, A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its connection with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1544–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navab, M.; Gharavi, N.; Watson, A.D. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Margaritis, M.; Lee, R.; Channon, K.; Antoniades, C. Statins as Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Atherogenesis: Molecular Mechanisms and Lessons from the Recent Clinical Trials. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, B.J.; Cox, P.J.; Evans, R.D.; Santer, P.; Miller, J.J.; Faull, O.K.; Magor-Elliot, S.; Hiyama, S.; Stirling, M.; Clarke, K. On the metabolism of exogenous ketones in humans. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminhotto, R.D.O.; Komino, A.C.M.; De Fatima Silva, F.; Andreotti, S.; Sertié, R.A.L.; Boltes Reis, G.; Lima, F.B. Oral β-hydroxybutyrate increases ketonemia, decreases visceral adipocyte volume and improves serum lipid profile in Wistar rats. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myette-Côté, É.; Caldwell, H.G.; Ainslie, P.N.; Clarke, K.; Little, J.P. A ketone monoester drink reduces the glycemic response to an oral glucose challenge in individuals with obesity: A randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myette-Côté, É.; Neudorf, H.; Rafiei, H.; Clarke, K.; Little, J.P. Prior ingestion of exogenous ketone monoester attenuates the glycaemic response to an oral glucose tolerance test in healthy young individuals. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ari, C.; Murdun, C.; Koutnik, A.P.; Goldhagen, C.R.; Rogers, C.; Park, C.; Bharwani, S.; Diamond, D.M.; Kindy, M.S.; D´Agostino, D.P.; et al. Exogenous ketones lower blood glucose level in rested and exercised rodent models. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, F.F.; Iqbal, N.; Seshadri, P.; Chicano, K.L.; Daily, D.A.; McGrory, J.; Williams, T.; Williams, M.; Gracely, E.J.; Stern, L. A Low-Carbohydrate as Compared with a Low-Fat Diet in Severe Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2074–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Benelli, M.; Brancaleoni, M.; Dainelli, G.; Merlini, D.; Negri, R. Middle and Long-Term Impact of a Very Low-Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diet on Cardiometabolic Factors: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional, Clinical Study. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2015, 22, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzaroma, E.; Toldo, S.; Farkas, D.; Seropian, I.M.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Salloum, F.N.; Kannan, H.R.; Menna, A.C.; Voelkel, N.F.; Abbate, A. The inflammasome promotes adverse cardiac remodeling following acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19725–19730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormsen, L.C.; Svart, M.; Thomsen, H.H.; Søndergaard, E.; Vendelbo, M.H.; Christensen, N.; Tolbod, L.P.; Harms, H.J.; Nielsen, R.; Wiggers, H.; et al. Ketone body infusion with 3-hydroxybutyrate reduces myocardial glucose uptake and increases blood flow in humans: A positron emission tomography study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, S. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Z. Fur Gefassmedizin 2016, 13, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, H.Y.; Karnchanasorn, R.; Chuang, L.M.; Chiu, K. Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Related Events in the Canagliflozin Type 2 Diabetes Clinical Program. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, A.L.; Buschur, E.O.; Buse, J.B.; Cohan, P.; Diner, J.C.; Hirsch, I.B. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: A potential complication of treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1687–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrannini, E.; Muscelli, E.; Frascerra, S.; Baldi, S.; Mari, A.; Heise, T.; Broedl, U.C.; Woerle, H.J. Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, J.C.; Verdin, E. β-hydroxybutyrate: Much more than a metabolite. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMPA-Kidney Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Dhingra, N.K.; Butler, J.; Anker, S.D.; Ferreira, J.P.; Filippatos, G.S.; Januzzi, J.; Lam, C.; Sattar, N.; Pell, B.; et al. Empagliflozin in the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in addition to background therapies and therapeutic combinations (EMPEROR-Reduced): A post-hoc analysis of a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Jamal Siddiqi, T.; Brueckmann, M.; Böhm, M.; Chopra, V.K.; Ferreira, J.P.; Januzzi, J.L.; Kaul, S.; Piña, I.L.; et al. Empagliflozin, Health Status, and Quality of Life in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: The EMPEROR-Preserved Trial. Circulation 2022, 145, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnostic NAFLD | Reference | Patients, n | Type of Study | Impact of the NAFLD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | ||||

| Stepanova and Younossi, 2012 [54] | 20,050 | Prospective | OR, 1.23 for CVD events | |

| Haring et al., 2009 [55] | 4160 | Prospective | HR, 6.22 for all-cause mortality and CVD | |

| Kim et al., 2012 [56] | 4023 | Cross-sectional | OR, 1.32 for CAC > 10 | |

| Targher et al., 2007 [57] | 2839 | Cross-sectional | OR, 1.49 for DKA DBP, and cerebrovascular disease in type 2 DM | |

| Tsutsumi T et al., 2021 [58] | 2306 | Prospective | HR, 1.08 independently with worsening CVD | |

| Hamaguchi et al., 2007 [59] | 1637 | Prospective | HR, 4.1 for nonfatal CVD events | |

| Yoshitaka and al, 2017 [60] | 1647 | Prospective | HR, 10.4 not overweight, 3.1 overweight for incident CV events | |

| Wong et al., 2011 [61] | 612 | Prospective | OR, 2.31 for significant coronary artery disease (>50% obstruction) | |

| Santos et al., 2007 [62] | 505 | Cross-sectional | OR, 1.73 for coronary calcification | |

| Mantovani et al., 2016 [63] | 286 | Retrospective | OR, 6.73 for incident cardiovascular events in type 1 diabetes | |

| CT | ||||

| Mahfood Hadad et al., 2016 [64] | 25,837 (11 studies) | Meta-analysis | RR, 1.77 for incident CVD, 1.43 for cardiovascular mortality | |

| Zhou et al., 2018 [65] | 8346 (6 studies) | Meta-analysis | OR, 2.20 for incident CVD in patients with diabetes | |

| Mellinger et al., 2015 [66] | 3014 | Cross-sectional | OR, 1.20 for CAC score >90th percentile for age | |

| Assy et al., 2010 [67] | 61 | Cross-sectional | OR, 2.03 for coronary calcification | |

| Ultrasound/CT | ||||

| Chen et al., 2010 [68] | 295 | Cross-sectional | OR, 2.46 for CAC > 100 | |

| Liver biopsy | ||||

| Simon et al., 2022 [42] | 422 | Prospective | HR, 2.15 for MACE | |

| Ji Hye Park et al., 2021 [69] | 398 | Cross-sectional | OR, 4.07 increased risk of ASCVD for NASH OR, 8.11 increased risk of ASCVD for advanced fibrosis | |

| Ekstedt et al., 2015 [70] | 229 | Retrospective | HR, 1.55 for CVD mortality | |

| Fatty Liver Index | ||||

| Chun HS et al., 2023 [71] | 78,762 | Cross-sectional | OR, 1.10 for CVD history in MAFLD OR, 1.40 for high probability of ASCVD in MAFLD OR, 1.22 for high probability of ASCVD in NAFLD | |

| Pais et al., 2016 [72] | 5671 | Retrospective | The severity of NAFLD correlates with CIMT and the severity of carotid plaque | |

| Lee J et al., 2020 [73] | 1173 | Prospective | OR, 1.70 for CAC progression in patients with NAFLD | |

| Pennisi et al., 2021 [74] | 542 | Cross-sectional | OR, 1.62 risk factors for ASCVD in patients with steatosis OR, 1.67 risk factors for ASCVD in patients with severe fibrosis | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

del Villar-Carrero, R.S.; Blanco, A.; Ruiz, L.D.; García-Blanco, M.J.; Segovia, R.C.; de la Garza, R.G.; Martínez-Urbistondo, D. Bridging Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Potential Role for Ketogenesis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030692

del Villar-Carrero RS, Blanco A, Ruiz LD, García-Blanco MJ, Segovia RC, de la Garza RG, Martínez-Urbistondo D. Bridging Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Potential Role for Ketogenesis. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(3):692. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030692

Chicago/Turabian Styledel Villar-Carrero, Rafael Suárez, Agustín Blanco, Lidia Daimiel Ruiz, Maria J. García-Blanco, Ramón Costa Segovia, Rocío García de la Garza, and Diego Martínez-Urbistondo. 2024. "Bridging Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Potential Role for Ketogenesis" Biomedicines 12, no. 3: 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030692