Parent Experiences in the NICU and Transition to Home

Abstract

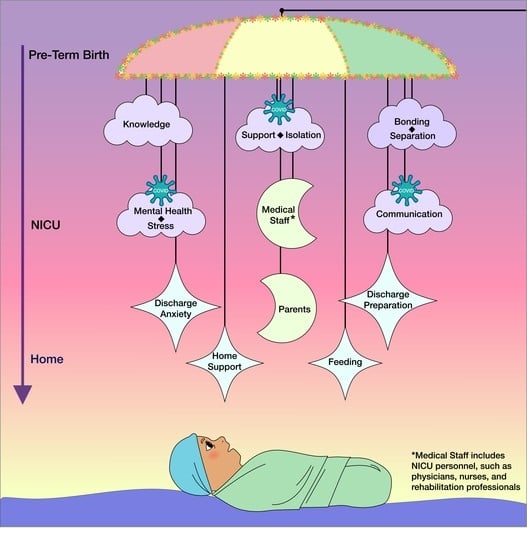

:1. Introduction

Research Questions

- (1)

- How do parents describe their experience while their preterm child was in the NICU?

- (1a)

- How did COVID-19 impact parents’ experiences while their child was in the NICU?

- (2)

- How do parents describe their transition from NICU to home?

- (2a)

- How did COVID-19 impact parents’ transition from NICU to home?

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Experience While in NICU

You know, to be completely honest, I was just actually wrapping my mind around being pregnant ... I was starting to show. So, I hadn’t really thought too far ahead into what life would look like with a newborn but that’s okay. She came when she came… I didn’t really picture a lot because like I said I was just trying to focus on the stage I was in at that point. I pictured, you know, just a big baby. A bigger baby. Just more time to relax, more time to not be as worried with everything that she does. Look at her development where she is right now versus having to adjust her age. Is she 9 weeks or is she negative 2 weeks. You know, is she all those kinds of things? Just, I kind of pictured it being a little bit easier. (P1)

Yeah, not being able to have my hands on my child and having a whole lot of people being able to see her and be around her. I couldn’t see her for a very long time… Her dad got to see her when she- when she came out, I didn’t get to see anything, I didn’t see her face, or nothing. Yeah, they took her straight to NICU. That was a lot for me. (P2)

Well it was obviously my first experience with a sick baby I would say. Both my first two kids who were born, we never had any medical issues…it was a completely different experience obviously., I was still having a baby and that was exciting to me. Of course I knew about some risk factors and I was scared. But definitely I did not expect what I saw when I entered the room, and I totally freaked out and I just wanted to run and forget about all this. (P3)

I feel like we really did get to bond, you know, it would be sad once I had to go back home cause I didn’t want it to get too late, but that was the only thing-I really did feel like I got to bond with her. (P5)

Parents described the competency and helpfulness of the medical staff, however they also discussed wanting to parent their own child, and how it was different because of the NICU environment. For example, a mother shared, “Yes, she was taken care of, but I wanted her to just be with her mom and I’m hoping that’s what she felt like too. Like, “I just wanna be with my mom” (P6).

Um, I knew, I knew a little bit of things because I’ve been an aunt at a very young age, so I kind of knew like a little bit of things…So it was like the things that I really knew, they still kind of applied but they didn’t. (P8)

When parents were part of discussions with medical professionals about their child, they described challenges with processing all of the information, “Honestly I really can’t remember. It wasn’t a lot of information with her that I can remember, no. A whole lot of it. (P7)

I took a very active role in the NICU and I was present, engaged with the nurses, engaged with the therapists, you know, I was there. I tried to ask questions, just be present. And I think that naturally lent itself for them to educate more if I’m sitting there going “tell me everything, I want to know. (P1)

I got a lot of second-hand information. I would speak with the father of my child, he would always have all of this information and I would be there everyday and they wouldn’t tell me the things that they would tell him so that was very frustrating…. My mom also had the code to access information and she would also be doing the same thing so I’m like, well, how come nobody’s mentioning these things to me and I’m here the most…So I didn’t really like that too much. (P2)

I’ve kind of blocked out the NICU experience, I feel like it may be a trauma response, but I don’t think about it very much, and when I do think about it, I think about it in very vague terms, I don’t think about the specifics very much. (P9)

Parents described reaching out but not having access to what was needed, “I asked for help but towards the end it was just like kind of, all me.” (P8) and “there was one point about midway through our NICU journey, I had a breakdown, cause I was so sad and I wanted to talk to someone” (P9).

We had certain obstacles where we wouldn’t get updated by some NICU nurses or just for the smallest things but like we explained to them, we live so far away you know the little things that happened may not mean much, you know, on a normal circumstance but we live so far away so any information that we can get to keep us- just informed- is appreciated. (P4)

3.1.1. Support Impacting Experience in NICU

I would say that- she had the best nurses that- honestly, I can’t even explain how great they were … Even like, going beyond what was expected of them, always asking—do you need anything, you know just making conversation, making me feel like I’m not alone. (P5)

Maybe just somebody to talk to, I think they actually do have that available, I just never called, … I just never utilized it, that might’ve been something I should’ve probably done but…talking to a stranger maybe is a little bit harder …maybe if it had come from somebody that I had trusted or … somebody that I had a good relationship with. (P11)

Several parents shared that they were able to seek out the support they needed from professionals they knew prior to the birth of their child, “before I delivered I had a counselor and so after I delivered early, I started seeing the counselor more. (P12).

Our NICU was not like open space, everyone had their own rooms so mostly I stayed in my room and I had my two...I knew parents, like their faces, but it wasn’t like you could stop there and talk in the corridor. It’s mostly doctors and nurses running here and there. (P3)

And they’re a support system for you, just to have somebody to talk to that has been through it. I guess cause it’s like when you’re in it it’s hard cause you try to explain it to other people what you’re going through, and [spouse] and I can’t talk to people, like our friends that had just had babies or have had babies cause it’s totally different. It’s totally different than a normal experience. (P11)

3.1.2. Impacts of COVID-19 on the Parents’ Experience While in the NICU

There was one person that actually (spouse’s name) and I did really like …he was an Episcopal priest, [he] would come by and check on (spouse’s name) and I and the girls, but I think you know, due to the Corona virus he wasn’t in there as much towards after. Visitation was limited and things like that. (P11)

Umm, I don’t know, I guess just how *pause* everything *pause* was so quick. I guess cause COVID is here, and you know, things are different. I didn’t really get a chance to meet a doctor, and my birth, was- it was, unexpec- *pause* I didn’t expect for things to go the way that they did. (P2)

3.2. Transition from NICU to Home

That last month the girls were in there, I know it was kind of tough, emotionally, it was, I was ready for them to come home and it was past their due date I guess that’s when I started to break down a little bit when it was past their due date cause they say that they usually come home around their due dates so I guess that was a little hard for me. (P11)

Many other parents found the idea of leaving the NICU anxiety provoking,

I didn’t know what to expect. I was so excited the day I was able to bring her home but I was anxious too and just like “is she gonna be okay?” And I felt like for me the transition was easy but I also know that I just wanted to do my best because of the experience she had in the NICU. (P6)

You kind of have this long journey in the NICU and it’s so long and day by day and boring, and just a little bit of growth, and then its “oh she’s going home tomorrow.” So, it’s kind of that transition, and you’re preparing for that transition always in the back of your mind, but it just comes really fast. (P1)

Cause they go from being taken care of 24/7 to just being at home with you. So it was nerve wracking. But she was fine, I don’t really remember any real issues that came up. It was more, I was just nervous leading up to her discharge. (P9)

I was scared because it’s something that’s a totally new experience and the baby that I didn’t know how to raise for the last four months, my nurse was more of a mother to him than I was at this point. So I was worried and didn’t know about the new environment and stuff. (P3)

But, like really, at the end, when it came down to him coming home, it was like uh, “Oh really, like, is he gonna be our baby now?” You know, I was like, “oh wait a minute, wait, he could stay for a little bit longer. I ain’t got nothing ready yet.” (P4)

But I would say that just maybe, I don’t know, having a little more prep even though you’re prepping the whole time, the actual thinking through “okay so if I’m actually gonna be mixing formula, I’m gonna need a bottle for that. If I’m gonna be washing I need drying racks. I need a syringe, I don’t have a syringe.” You know, all those things, the logistical, how am I gonna do what they do at my house. Maybe more like a trial run. I know some hospitals do like the rooming-in, we didn’t do that at my hospital. But, that would’ve been nicer cause we were scrambling “okay well they have all the supplies, we don’t have all the supplies. What do we do?” (P1)

Yes, they [nurses] answered a lot of my questions. I would tell them as time got closer for her to come home how scared I was and they just let me know that they’re here if I need anything and that it’s a great experience and that I can do it. (P5)

3.2.1. First few Weeks at Home

When we got home, we had like a little, you know, a little disagreement. Oh, I don’t know, I think we were just so, like, “oh my goodness- how do I feed the bottle, how do I do it,” you know, just because it’s a whole new environment. We don’t have the nurses, we don’t have the doctors to tell us everything. But I think after a week I was just in the groove of it. (P4)

I really just take care of her and protect her and every day with her is amazing with me, for me. It’s just seeing her grow, seeing her develop more, trying to do more than what everybody really figured that she would really do. She came home doing everything that a normal- she came home in 5 months. (P7)

Their digestive systems to be advanced enough now where it’s like okay now we can feed them at the same time and they’re not throwing up their feeds every time. Cause that was a big thing for the girls too when they first came home. They would- that was always scary too because they’d take their feed and they’d throw up and it’s like, okay, did they get enough? And, you know, so that was a little scary there for the first week or so. (P11)

Really, to me, caring for a newborn is built-in, you to know how to do it and understand how to do it. But for a preemie newborn that’s coming home with a feeding tube, to me, I feel like is more stressful to a regular baby coming home cause you have more to do with them, more that comes along with them. But, at the end of the day, you still, you know, you’re fine with it. That’s how we always been. We just go with the flow. We fine with it. They well taken care of. It’s just, it comes with a lot but it’s worth it. (P7)

Feeding has been quite a challenge, and growing. So we have been doing different medications and different combinations of food, breast milk, formula, positions, working with speech therapy to get her to not have pain when she eats so she’ll want to eat so she’ll grow. So, that’s been our biggest challenge. But everything is perfect. She’s not on oxygen, she doesn’t have any tubes or lines or monitors or anything. She’s just a perfect little baby who doesn’t want to eat. (P1)

3.2.2. Impacts of COVID-19 on the Transition Process

We thought that was hard and now the girls are home and so we have twins and yeah, every three hours, um, waking up every three hours and then on top of the Coronavirus, it’s been quite challenging, cause you can’t really get help from anybody…We thought our moms were going to be more helpful and [spouse’s] mom, she’s scared to leave her apartment and everything like that, and my mom is kind of the opposite, I don’t think taking it as seriously as she should. (P11)

Havin’ a COVID baby…he really got adjusted to seeing people like we doin’ now, video time, you know. His grandmother, my grandmother, my mom, you know everybody. So he loves the camera and he’ll show off for the camera, he’ll talk, he’ll play, and stuff. (P4)

Well, it’s been a little bit confusing, like whether I should send my son to school or not, cause I’m not that worried about my son getting COVID, cause you know it is not that common in 3 year olds to get a very serious form of it. But you know, I’m not really sure how susceptible she is to it. And no one really does. That’s been the hardest, worrying about pathogens. You know preemies are different, but she’s been a good baby so far. She’s sleeping well, once we got the reflux controlled. She really started sleeping nicely at night. (P9)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice and Policy

4.2. Implications for Research

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- As you reflect on your journey over the past few months, what stands out the most to you?

- (2)

- What did you know about infant development and parent-infant relationships prior to the birth of your child?

- (a).

- How did you know this information? Was it related to your educational experience, occupation, previous experience parenting, or other factors?

- (b).

- What did you envision when you pictured the birth of your child and the first few weeks at home?

- (3)

- What supports did you have as you transitioned home from the NICU?

- (a).

- Probe if no immediate response: This could include developmental or medical information, contact information, planning for logistics with medical follow-up, transportation, etc.

- (b).

- What supports would have been useful?

- (4)

- What are your child’s current needs, related to their medical history?

- (5)

- Due to the NICU experience and the specific needs you just described, how do you view your role as mom or dad? What are the important day-to-day events?

- (6)

- Who is currently supporting you and your child based on your child’s specific needs? This could include medical personnel, therapists, community agencies, etc.

- (a).

- Who comprises your emotional support network? Do you have local support?

- (b).

- Who comprises your informational support network? Who do you turn to when you have questions about your child?

- (c).

- Are your material needs met or what needs do you have? For example, do you have access to all the medical equipment needed to support your child, have transportation needs, or has your work schedule/hours changed due to the support needs for your child?

- (7)

- What do you know about early intervention or Part C services?

- (a).

- Prompt if no immediate response: This is a program for infants and toddlers with or at-risk for disabilities and developmental delays. Your child may qualify to receive services due to their preterm birth.

- (b).

- Describe any contact you have you had with Early Intervention / Part C. This could include a conversation with a service coordinator prior to discharge from the NICU, assessments, or visits at home with an educator or therapist.

- (c).

- (When was the first point of contact with EI/Part C?

- (d).

- Do you have an IFSP developed?

- (8)

- As you think about supporting your child’s growth and development, what sources of information have been useful?

- (a).

- Probe: These could include conversations with other parents, medical staff, or therapists, reading books, looking at websites, etc.

- (9)

- SPEEDI_Early Participants only: Was the frequency of the visits too much, just right, or not enough? Why?

- (a).

- You recently completed Phase 1, which was the part of the study in the NICU when you met with the therapist 5 times in 2–3 weeks -

- How convenient was it to schedule visits while in the NICU?

- What were the biggest barriers to scheduling visits?

- How many caregivers participated directly in SPEEDI visits?

- As a caregiver that was present during SPEEDI visits, did you feel capable to share information with others (i.e., non-attending parent, grandparent)? What would have been beneficial for you in sharing the information?

- Were you able to implement what you learned from the therapist into your daily interaction with you child immediately? Or did you feel like it only worked during therapy or it took time for the work to pay off?

- (10)

- What are your favorite activities to do with your child?

- (11)

- What concerns do you have about your child’s development?

- (12)

- Do you have any concerns about your ability to meet your child’s needs?

- (a).

- Do you have any concerns about your ability to bond and care for your child?

- (13)

- Are there any other aspects of the transition home from the NICU or parenting during these first few months that I should know?

- (a).

- Probe: You may want to reflect on if parenting was different than you expected it to be, in regards to the medical component as well as your ability to socialize with friends/family, view yourself as a mom/dad/caregiver, support your other children, work, engage in previous routines (exercise, etc.)

References

- 2022 March of Dimes Report Card. Available online: https://marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/2022-MarchofDimes-ReportCard-UnitedStates.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Ricci, M.F.; Shah, P.S.; Moddemann, D.; Alvaro, R.; Ng, E.; Lee, S.K.; Synnes, A.; Network, C.N. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Infants < 29 Weeks’ Gestation Born in Canada Between 2009 and 2016. J. Pediatr. 2022, 247, 60–66.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badawi, N.; McIntyre, S.; Hunt, R.W. Perinatal care with a view to preventing cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givrad, S.; Hartzell, G.; Scala, M. Promoting infant mental health in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): A review of nurturing factors and interventions for NICU infant-parent relationships. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 154, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonya, J.; Feldman, K.; Brown, K.; Stein, M.; Keim, S.; Boone, K.; Rumpf, W.; Ray, W.; Chawla, N.; Butter, E. Human interaction in the NICU and its association with outcomes on the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 127, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgoulas, A.; Jones, L.; Laudiano-Dray, M.P.; Meek, J.; Fabrizi, L.; Whitehead, K. Sleep–wake regulation in preterm and term infants. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, J.K.; Gutierrez, T. Musculoskeletal implications of preterm infant positioning in the NICU. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2002, 16, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, R.E. Sensitive parenting: A key moderator of neonatal cortical dysmaturation and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born very preterm. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 92, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.V.; Chau, V.; Synnes, A.; Miller, S.P.; Grunau, R.E. Brain development and maternal behavior in relation to cognitive and language outcomes in preterm-born children. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 92, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberger, E.; Canvasser, J.; Hall, S.L. Enhancing NICU parent engagement and empowerment. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 27, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knighton, A.J.; Bass, E.J. Implementing family-centered rounds in hospital pediatric settings: A scoping review. Hosp. Pediatr. 2021, 11, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, P.A.; Albanese, A.; Grunberg, V.A.; Chuo, J.; Patterson, C.A. Quality improvement and research across fetal and neonatal care settings. In Behavioral Health Services with High-Risk Infants and Families: Meeting the Needs of Patients, Families, and Providers in Fetal, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, and Neonatal Follow-Up Settings; Dempsy, A., Cole, J., Saxton, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, E.; Apaydin, Z.K.; Alay, B.; Dincer, Z.; Cigri, E. COVID-19 history increases the anxiety of mothers with children in intensive care during the pandemic in Turkey. Children 2022, 9, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.K.; Cho, I.Y.; Yun, J.Y.; Park, B. Factors influencing neonatal intensive care unit nurses’ parent partnership development. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 68, e27–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Kase, J. The evolution of parental self-efficacy in knowledge and skill in the home care of preterm infants. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Individ. Med. 2017, 6, e060118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Lee, E.; Kim, K.; Namkoong, K.; Park, E.; Rha, D. Progress of PTSD symptoms following birth: A prospective study in mothers of high-risk infants. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veenendaal, N.R.; Labrie, N.H.M.; Mader, S.; van Kempen, A.A.M.W.; van der Schoor, S.R.D.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Group, C.S. An international study on implementation and facilitators and barriers for parent-infant closeness in neonatal units. Pediatr. Investig. 2022, 6, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Spittle, A.; Anderson, P.J.; O’Brien, K. A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after the preterm birth of their infant. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumello, C.; Candelori, C.; Cofini, M.; Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L.; Paciello, M.; Babore, A. Mothers’ depression, anxiety, and mental representations after preterm birth: A study during the infant’s hospitalization in a neonatal intensive care unit. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ionio, C.; Colombo, C.; Brazzoduro, V.; Mascheroni, E.; Confalonieri, E.; Castoldi, F.; Lista, G. Mothers and fathers in NICU: The impact of preterm birth on parental distress. Eur. J. Psychol. 2016, 12, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, J.; Fowler, C.; Petty, J.; Whiting, L. The transition home of extremely premature babies: An integrative review. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 27, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, C.F.; Lee, Y.; Kim, H.N. Paternal and maternal concerns for their very low-birth-weight infants transitioning from the NICU to home. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2014, 28, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C.; Harvey, M. “We weren’t prepared for this”: Parents’ experiences of information and support following the premature birth of their infant. Infants Young Child. 2019, 32, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, B.; Pinto, N. Optimizing discharge from intensive care and follow-up strategies for pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lakshmanan, A.; Kubicek, K.; Williams, R.; Robles, M.; Vanderbilt, D.L.; Mirzaian, C.B.; Friedlich, P.S.; Kipke, M. Viewpoints from families for improving transition from NICU-to-home for infants with medical complexity at a safety net hospital: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feehan, K.; Kehinde, F.; Sachs, K.; Mossabeb, R.; Berhane, Z.; Pachter, L.M.; Brody, S.; Turchi, R.M. Development of a multidisciplinary medical home program for NICU graduates. Matern. Child Health J. 2020, 24, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raho, L.; Bucci, S.; Bevilacqua, F.; Grimaldi, T.; Dotta, A.; Bagolan, P.; Aite, L. The NICU during COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on maternal pediatric medical traumatic stress (PMTS). Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 39, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Zutshi, A. Trauma-informed care in the neonatal intensive care unit: Through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus 2022, 14, e30307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, L.; Biban, P.; Janos, J.; Lavelli, M.; Langfus, J.; Tsai, A.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Stefana, A. The collateral impact of COVID-19 emergency on Neonatal Intensive Care Units and family-centered care: Challenges and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 630594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, C.; Ferrari, A.; Siskind, D.; Whiteford, H.; Harris, M. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Holditch-Davis, D.; Miles, M.S. Effects of maternal depressive symptoms and infant gender on the interactions between mothers and their medically at-risk infants. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 37, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erdei, C.; Feldman, N.; Koire, A.; Mittal, L.; Liu, C.H.J. COVID-19 pandemic experiences and maternal stress in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Children 2022, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merritt, L.; Verklan, M.T. The implications of COVID-19 on family-centered care in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2022, 41, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.D.; Swanson, J.R. Visitation restrictions: Is it right and how do we support families in the NICU during COVID-19? J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy Mahoney, A.; White, R.D.; Velasquez, A.; Barrett, T.S.; Clark, R.H.; Ahmad, K.A. Impact of restrictions on parental presence in neonatal intensive care units related to coronavirus disease 2019. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Kazmi, S.H.; Schneider, S.; Angert, R. Virtual care across the Neonatal Intensive Care continuum. Cureus 2023, 15, e35183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, J.L.; Sauers-Ford, H.S.; Williams, J.; Ranu, J.; Tancredi, D.J.; Hoffman, K.R. Virtual family-centered rounds in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusing, S.C.; Burnsed, J.C.; Brown, S.E.; Harper, A.D.; Hendricks-Munoz, K.D.; Stevenson, R.D.; Thacker, L.R., II; Molinini, R.M. Efficacy of supporting play exploration and early development intervention in the first months of life for infants born very preterm: 3-Arm randomized clinical trial protocol. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Maietta, R.C. Qualitative research. In Handbook of Research Design & Social Measurement, 6th ed.; Miller, D.C., Salkind, N.J., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Given, L.M. Phenomenology. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish, F.; Gillespie, A.; Zittoun, T. Collaborative analysis of qualitative data. SAGE Handb. Qual. Data Anal. 2013, 79, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brantlinger, E.; Jimenez, R.; Klingner, J.; Pugach, M.; Richardson, V. Qualitative studies in special education. Except. Children. 2005, 71, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “Big-Tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Woo, D.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, M.; Kim, D.H. Development of healthcare service design concepts for NICU parental education. Children 2021, 8, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz, D.S.; Baxt, C.; Evans, J.R. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2010, 17, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givrad, S.; Dowtin, L.L.; Scala, M.; Hall, S.L. Recognizing and mitigating infant distress in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J. Neonatal Nurs. 2020, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.C.; Love, K.; Goyer, E. NICU discharge preparation and transition planning: Guidelines and recommendations. J. Perinatol. 2022, 42, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, I.B.; Craig, J.W.; Zeanah, P. NICU discharge planning and beyond: Recommendations for parent psychosocial support. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, S24–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Novak, J.L.; Vittner, D. Parent engagement in the NICU. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 27, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; Waddington, C.; O’Brien, K. Family integrated care for preterm infants. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2020, 32, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der voort, A.; Juffer, F.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. Sensitive parenting is the foundation for secure attachment relationships and positive social-emotional development of children. J. Child. Serv. 2014, 9, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouldes, T.A. Fostering resilience to very preterm birth through the caregiving environment. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2238095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treyvaud, K.; Thompson, D.K.; Kelly, C.E.; Loh, W.Y.; Inder, T.E.; Cheong, J.L.; Doyle, L.W.; Anderson, P.J. Early parenting is associated with the developing brains of children born very preterm. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 35, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, E.C.; Hofheimer, J.A.; O’Shea, T.M.; Kilbride, H.; Carter, B.S.; Check, J.; Helderman, J.; Neal, C.R.; Pastyrnak, S.; Smith, L.M.; et al. Analysis of neonatal neurobehavior and developmental outcomes among preterm infants. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2222249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adair, R.H. Social-emotional development in early childhood: Normative, NICU considerations, and application in NICU follow-up programs for at-risk infants and their families. In Follow-Up for NICU Graduates: Promoting Positive Developmental and Behavioral Outcomes for At-Risk Infants; Needelman, H., Jackson, B.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, L.S.; Kriz, R.M.; Bisgaard, R.; Gay, C.L.; Sossaman, S.; Sossaman, J.; Cormier, D.M.; Joe, P.; Sasinski, J.K.; Kim, J.H. Parent readiness for their preterm infant’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit discharge. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 37, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporali, C.; Pisoni, C.; Naboni, C.; Provenzi, L.; Orcesi, S. Challenges and opportunities for early intervention and neurodevelopmental follow-up in preterm infants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child: Care Health Dev. 2021, 47, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcullen, M.L.; Kandasamy, Y.; Evans, M.; Kanagasignam, Y.; Atkinson, I.; van der Valk, S.; Vignarajan, J.; Baxter, M. Parents using live streaming video cameras to view infants in a regional NICU: Impacts upon bonding, anxiety and stress. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2022, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardo, G.; Riccitelli, M.; Giordano, M.; Proietti, F.; Sordino, D.; Longini, M.; Buonocore, G.; Perrone, S. Rooming-in reduces salivary cortisol level of newborn. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 2845352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratantoni, K.; Soghier, L.; Kritikos, K.; Jacangelo, J.; Herrera, N.; Tuchman, L.; Glass, P.; Streisand, R.; Jacobs, M. Giving parents support: A randomized trial of peer support for parents after NICU discharge. J. Perinatol. 2022, 42, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Race | ||

| Mother (n = 12) | Father (n = 12) | |

| Asian | 1 | 1 |

| Black/African American | 4 | 6 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 |

| White | 5 | 4 |

| Biracial | 1 | 0 |

| Not Reported | 1 | 1 |

| Highest Educational Level | ||

| Mother (n = 12) | Father (n = 12) | |

| Some High School | 1 | 1 |

| High School/GED | 2 | 3 |

| Some College | 1 | 2 |

| Associate’s degree | 0 | 1 |

| 4 year degree | 4 | 1 |

| Graduate degree | 3 | 3 |

| Not reported | 1 | 1 |

| Birth Weight | |

| 600–699 | 1 |

| 700–799 | 4 |

| 800–899 | 2 |

| 900–999 | 3 |

| 1000–1099 | 2 |

| Weeks Gestation | |

| 24 | 1 |

| 25 | 1 |

| 26 | 4 |

| 27 | 5 |

| 28 | 1 |

| Days in NICU | |

| 56–62 | 1 |

| 63–76 | 1 |

| 77–90 | 1 |

| 91–104 | 3 |

| 105–118 | 1 |

| 119–132 | 3 |

| 133–146 | 0 |

| 147–160 | 1 |

| 161–174 | 0 |

| 175 | 1 |

| Assisted Ventilation | |

| None | 0 |

| 1–2 days | 0 |

| 3–14 days | 1 |

| 15–28 days | 2 |

| 29 or more days | 9 |

| Periventricular Hemorrhage | |

| None | 9 |

| Grade I or II | 1 |

| Grade III or IV | 2 |

| Neonatal Medical Index | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 9 |

| Necrotizing Enterocolitis | |

| No | 9 |

| Yes | 3 |

| Race | |

| Asian | 1 |

| Black/African American | 4 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 |

| White | 4 |

| Biracial | 2 |

| Not Reported | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spence, C.M.; Stuyvenberg, C.L.; Kane, A.E.; Burnsed, J.; Dusing, S.C. Parent Experiences in the NICU and Transition to Home. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20116050

Spence CM, Stuyvenberg CL, Kane AE, Burnsed J, Dusing SC. Parent Experiences in the NICU and Transition to Home. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):6050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20116050

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpence, Christine M., Corri L. Stuyvenberg, Audrey E. Kane, Jennifer Burnsed, and Stacey C. Dusing. 2023. "Parent Experiences in the NICU and Transition to Home" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 6050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20116050