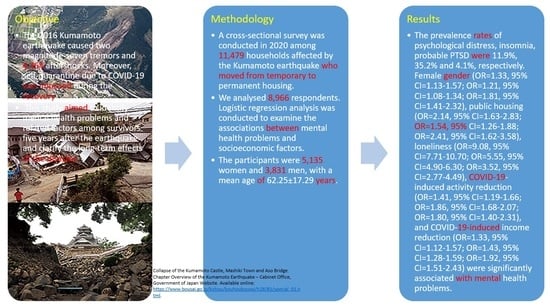

Depression, Insomnia, and Probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Survivors of the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake and Related Factors during the Recovery Period Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Mental Health Problems

2.2.1. Psychological Distress (K6)

2.2.2. Insomnia (Athens Insomnia Scale)

2.2.3. Probable PTSD

2.3. Other Variables

2.3.1. Attributes

2.3.2. Housing Conditions

2.3.3. Social Relationships

2.3.4. Self-Reported Impact of COVID-19

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence Rates of Mental Health Problems

4.2. Factors Associated with Mental Health Problems

4.2.1. Attributes

4.2.2. Type of Permanent Housing

4.2.3. Social Relationships

4.2.4. Factors Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.3. Limitations and Significance of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Japan Meteorological Agency. The 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake -Portal-. Available online: https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/en/2016_Kumamoto_Earthquake/2016_Kumamoto_Earthquake.html (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Japanese).

- Chapter Overview of the Kumamoto Earthquake—Kumamoto City Website. Available online: https://www.city.kumamoto.jp/common/UploadFileDsp.aspx?c_id=5&id=19060&sub_id=1&flid=134903 (accessed on 31 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Hashimoto, M.; Savage, M.; Nishimura, T.; Horikawa, H.; Tsutsumi, H. 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence and its impact on earthquake science and hazard assessment. Earth Planets Space 2017, 69, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mainichi Shimbun. Strongest Aftershock since April Jolts Kumamoto. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20160613/p2a/00m/0na/001000c (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Fire and Disaster Management Agency, Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Earthquake with Seismic Origin in the Kumamoto District, Kumamoto Prefecture; Report No. 120; Fire and Disaster Management Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. Available online: https://www.fdma.go.jp/bn/2016/detail/960.html (accessed on 31 January 2022). (In Japanese)

- Passing on Memories of the Kumamoto Earthquake for the Future to Learn from Its Gallery-Style Field Museum. Available online: https://kumamotojishin-museum.com/about/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Ando, S.; Kuwabara, H.; Araki, T.; Kanehara, A.; Tanaka, S.; Morishima, R.; Kondo, S.; Kasai, K. Mental health problems in a community after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011: A systematic review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, J.; Funakoshi, S.; Tomita, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsuoka, H. Longitudinal characteristics of resilience among adolescents: A high school student cohort study to assess the psychological impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sato, K.; Amemiya, A.; Haseda, M.; Takagi, D.; Kanamori, M.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N. Postdisaster changes in social capital and mental health: A natural experiment from the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 189, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ergün, D.; Şenyüz, S. Prolonged grief disorder among bereaved survivors after the 2011 Van Earthquake in Turkey. Death Stud. 2021, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaratou, H.; Paparrigopoulos, T.; Anomitri, C.; Alexandropoulou, N.; Galanos, G.; Papageorgiou, C. Sleep problems six-months after continuous earthquake activity in a Greek island. Psychiatriki 2018, 29, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.; Ospina-Duque, J.; Barrera-Valencia, M.; Escobar-Rincón, J.; Ardila-Gutiérrez, M.; Metzler, T.; Marmar, C. Posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression symptoms, and psychosocial treatment needs in Colombians internally displaced by armed conflict: A mixed-method evaluation. Psychol. Trauma 2011, 3, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orui, M.; Saeki, S.; Harada, S.; Hayashi, M. Practical report of disaster-related mental health interventions following the Great East Japan Earthquake during the COVID-19 pandemic: Potential for suicide prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, I.C.N.; Dos Santos Costa, A.C.; Islam, Z.; Jain, S.; Goyal, S.; Mohanan, P.; Essar, M.Y.; Ahmad, S. Typhoons during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: Impact of a double crises on mental health. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 1–4, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Medved, S.; Imširagić, A.S.; Salopek, I.; Puljić, D.; Handl, H.; Kovač, M.; Peleš, A.M.; Štimac Grbic, D.; Romančuk, L.; MuŽić, R.; et al. Case series: Managing severe mental illness in disaster situation: The Croatian experience after 2020 earthquake. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 795661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, F.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Fang, Y.; Pham, T.S.; Liu, X.; Fan, F. Bidirectional associations between insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depressive symptoms among adolescent earthquake survivors: A longitudinal multiwave cohort study. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistical Survey Division, Kumamoto Prefecture. Kumamoto Prefecture Population Estimation Report (Annual Report). Available online: https://www.pref.kumamoto.jp/soshiki/20/78661.html (accessed on 25 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Sugisawa, H.; Shinoda, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Kumagai, T. Cognition and Implementation of disaster preparedness among Japanese dialysis facilities. Int. J. Nephrol. 2021, 2021, 6691350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kawakami, N.; Saitoh, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakane, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Iwata, N.; Uda, H.; Nakane, H.; et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Tanji, F.; Zhang, S.; Sugawara, Y.; Tsuji, I. The impact of psychological distress on incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: The Ohsaki Cohort 2006 study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Institute of Health and Nutrition Health Japan21 (2nd Round). Analysis and Evaluation Project. Available online: https://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/kenkounippon21/kenkounippon21/genjouchi.html (accessed on 25 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Hagiwara, Y.; Sekiguchi, T.; Sugawara, Y.; Yabe, Y.; Koide, M.; Itaya, N.; Yoshida, S.; Sogi, Y.; Tsuchiya, M.; Tsuji, I.; et al. Association between sleep disturbance and new-onset subjective knee pain in Great East Japan Earthquake survivors: A prospective cohort study in the Miyagi prefecture. J. Orthop. Sci. 2018, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Fukasawa, M.; Obara, A.; Kim, Y. Mental health distress and related factors among prefectural public servants seven months after the great East Japan Earthquake. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Sugawara, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Sugiyama, K.; Kaiho, Y.; Tanji, F.; Tsuji, I. Association between housing type and γ-GTP increase after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 189, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, I.; Nakajima, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Inoue, Y. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Athens Insomnia Scale. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 67, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. Athens Insomnia Scale: Validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 48, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, Y.; Nishitani, N.; Sakakibara, H. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in blue-collar and white-collar male workers. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2015, 57, 130–139. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Foa, E.B.; Cashman, L.; Jaycox, L.; Perry, K. The validation of a self-report measure of post-traumatic stress disorder: The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol. Assess. 1997, 9, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.; Ujiie, Y.; Nagae, N.; Niwa, M.; Kamo, T.; Lin, M.; Hirohata, S.; Kim, Y. A new short version of the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale: Validity among Japanese adults with and without PTSD. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017, 8, 1364119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Itoh, M.; Ujiie, Y.; Nagae, N.; Niwa, M.; Kamo, T.; Lin, M.; Hirohata, S.; Kim, Y. The Japanese version of the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale: Validity in participants with and without traumatic experiences. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017, 25, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Ueki, M.; Yamada, M.; Tamiya, G.; Motoike, I.N.; Saigusa, D.; Sakurai, M.; Nagami, F.; Ogishima, S.; Koshiba, S.; et al. Improved metabolomic data-based prediction of depressive symptoms using nonlinear machine learning with feature selection. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, H.; Study on Mental Health of Disaster Victims. Survey on the Health Status of the Victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake in Miyagi Prefecture. Comprehensive Research Project on Health, Safety and Crisis Management Measures. Subsidy for Research Project to Promote Health and Labor Administration (H25-Kenki-Specification-002(Reconstruction). Report of the Research Project. 2019. Available online: https://www.ch-center.med.tohoku.ac.jp/report-pdf/h30-report.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Kumamoto Prefectural Government, Department of Health and Welfare, Child and Disability Welfare Bureau, Support Division for Persons with Disabilities. Results of the 1st Mental and Physical Health Survey. Available online: https://www.pref.kumamoto.jp/uploaded/life/84992_111376_misc.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022). (In Japanese)

- Hayashi, H. Survey on the Health Status of Victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Special Research. Health, Labor and Welfare Science Research Grant, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Special Research Project (H23-Tokubetsu-Shitei-002). Report of the Research Project. 2012. Available online: https://www.ch-center.med.tohoku.ac.jp/report-pdf/h23-report.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022). (In Japanese).

- Tsuchiya, M.; Aida, J.; Hagiwara, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Sato, M.; Watanabe, T.; Tomita, H.; Nemoto, E.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Periodontal disease is associated with insomnia among victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake: A panel study initiated three months after the disaster. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2015, 237, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogg, D.; Kingham, S.; Wilson, T.M.; Ardagh, M. The effects of relocation and level of affectedness on mood and anxiety symptom treatments after the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 152, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumamoto City. Precinct-Based Health Town Development. Available online: https://www.city.kumamoto.jp.e.fm.hp.transer.com/hpkiji/pub/detail.aspx?c_id=5&type=top&id=31602 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Japan Meteorological Agency. Local Government Seismic Intensity Meter Waveforms. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/eqev/data/kyoshin/jishin/1604150003_kumamoto/index2.html (accessed on 22 March 2022). (In Japanese).

- Tempesta, D.; Curcio, G.; De Gennaro, L.; Ferrara, M. Long-term impact of earthquakes on sleep quality. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Tadakawa, M.; Koga, S.; Nagase, S.; Yaegashi, N. Premenstrual symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder in Japanese high school students 9 months after the great East-Japan earthquake. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2013, 230, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; He, H.; Qu, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among adult survivors 8 years after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, Y.; Aida, J.; Tsuji, T.; Miyaguni, Y.; Tani, Y.; Koyama, S.; Matsuyama, Y.; Sato, Y.; Tsuboya, T.; Nagamine, Y.; et al. Does type of residential housing matter for depressive symptoms in the aftermath of a disaster? Insights from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kotozaki, Y.; Tanno, K.; Sakata, K.; Takusari, E.; Otsuka, K.; Tomita, H.; Sasaki, R.; Takanashi, N.; Mikami, T.; Hozawa, A.; et al. Association between the social isolation and depressive symptoms after the great East Japan earthquake: Findings from the baseline survey of the TMM CommCohort study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Sekiguchi, T.; Yabe, Y.; Hagiwara, Y.; Tsuji, I. Social trust predicts sleep disorder at 6 years after the Great East Japan earthquake: Data from a prospective cohort study. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Cutrona, C.E. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bris, P.; Bendito, F. Impact of Japanese post-disaster Temporary Housing Areas’ (THAs) design on mental and social health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| n = 8966 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 3831 | 42.7 |

| Female | 5135 | 57.3 | |

| Age | Mean ± sd (years) | 62.25 | ±17.29 |

| 18–64 years old | 4208 | 46.9 | |

| 65 years old | 4758 | 53.1 | |

| Cohabitant | None | 1805 | 20.1 |

| Yes | 7077 | 78.9 | |

| Temporary housing category | Prefabricated temporary housing | 544 | 6.1 |

| Temporary housing in the private sectors | 7892 | 88.0 | |

| Temporary housing in the public sectors | 528 | 5.9 | |

| Current residence | Owned house | 5072 | 56.6 |

| Houses for rent | 2383 | 26.6 | |

| Public housing | 1116 | 12.4 | |

| Public housing for disaster | 116 | 1.3 | |

| Hospitals and institutions | 66 | 0.7 | |

| Other | 159 | 1.8 | |

| Change of residential school district | None | 5462 | 61.8 |

| Yes | 3065 | 34.7 | |

| I don’t know | 312 | 3.5 | |

| Mental illness | None | 5687 | 63.4 |

| Yes | 469 | 5.2 | |

| Loneliness | None | 6913 | 77.1 |

| Yes | 1867 | 20.8 | |

| Community participation | No information of such events | 1111 | 12.4 |

| None | 5677 | 63.3 | |

| Yes | 1991 | 22.2 | |

| Decrease in activity opportunities due to COVID-19 | None | 4418 | 49.3 |

| Yes | 4316 | 48.1 | |

| Decrease in income due to COVID-19 | None | 5533 | 61.7 |

| Yes | 2956 | 33.0 |

| n = 8966 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| K6 score | |||

| K6 ≥ 5 | 2663 | 32.8 | |

| K6 ≥ 10 | 964 | 11.9 | |

| K6 ≥ 13 | 428 | 5.3 | |

| Psychological distress (K6 ≥ 10) | |||

| None | 7158 | 88.1 | |

| Yes | 964 | 11.9 | |

| Insomnia (AIS-J ≥ 6) | |||

| None | 5398 | 64.8 | |

| Yes | 2932 | 35.2 | |

| Probable PTSD | |||

| None | 8601 | 95.9 | |

| Yes | 365 | 4.1 | |

| n = 8966 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distress | Insomnia | Probable PTSD | ||||||||||||||

| Applicable | Not Applicable | Applicable | Not Applicable | Applicable | Not Applicable | |||||||||||

| n = 964 | n = 7158 | p Value | n = 2932 | n = 5398 | p Value | n = 365 | n = 8601 | p Value | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Gender | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Male | 354 | 36.7 | 3140 | 43.9 | 1168 | 39.8 | 2436 | 45.1 | 111 | 30.4 | 3720 | 43.3 | ||||

| Female | 610 | 63.3 | 4018 | 56.1 | 1764 | 60.2 | 2962 | 54.9 | 254 | 69.6 | 4881 | 56.7 | ||||

| The elderly | 0.304 | <0.001 | 0.002 | |||||||||||||

| None (18–64 years old) | 499 | 51.8 | 3579 | 50.0 | 1326 | 45.2 | 2735 | 50.7 | 142 | 38.9 | 4066 | 47.3 | ||||

| Yes (over 65 years) | 465 | 48.2 | 3579 | 50.0 | 1606 | 54.8 | 2663 | 49.3 | 223 | 61.1 | 4535 | 52.7 | ||||

| Live-in | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 667 | 69.6 | 5843 | 82.0 | 2172 | 74.6 | 4492 | 83.6 | 252 | 69.4 | 6825 | 80.1 | ||||

| None | 292 | 30.4 | 1282 | 18.0 | 739 | 25.4 | 881 | 16.4 | 111 | 30.6 | 1694 | 19.9 | ||||

| Temporary housing category | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.016 | |||||||||||||

| Prefabricated temporary housing | 58 | 6.0 | 410 | 5.7 | 171 | 5.8 | 318 | 5.9 | 30 | 8.2 | 514 | 6.0 | ||||

| Temporary housing (rental) | 810 | 84.1 | 6385 | 89.2 | 2536 | 86.5 | 4824 | 89.4 | 304 | 83.3 | 7588 | 88.2 | ||||

| Temporar housing (public sectors) | 95 | 9.9 | 362 | 5.1 | 224 | 7.6 | 255 | 4.7 | 31 | 8.5 | 497 | 5.8 | ||||

| Current residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Owned house | 382 | 39.7 | 4295 | 60.2 | 1452 | 49.7 | 3324 | 61.9 | 144 | 39.7 | 4928 | 57.6 | ||||

| Houses for rent | 317 | 32.9 | 1860 | 26.1 | 864 | 29.6 | 1367 | 25.4 | 119 | 32.8 | 2264 | 26.5 | ||||

| Public housing | 221 | 22.9 | 747 | 10.5 | 488 | 16.7 | 512 | 9.5 | 79 | 21.8 | 1037 | 12.1 | ||||

| Public housing for disaster | 17 | 1.8 | 71 | 1.0 | 41 | 1.4 | 59 | 1.1 | 12 | 3.3 | 104 | 1.2 | ||||

| Other | 26 | 2.7 | 156 | 2.2 | 77 | 2.6 | 112 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.5 | 216 | 2.5 | ||||

| Change of residential school district | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| None | 454 | 50.4 | 4528 | 65.8 | 1617 | 58.4 | 3504 | 67.5 | 189 | 54.9 | 5273 | 64.4 | ||||

| Yes | 446 | 49.6 | 2350 | 34.2 | 1152 | 41.6 | 1688 | 32.5 | 155 | 45.1 | 2910 | 35.6 | ||||

| Loneliness | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| None | 317 | 33.6 | 6050 | 85.2 | 1686 | 57.8 | 4862 | 90.3 | 171 | 47.5 | 6742 | 80.1 | ||||

| Yes | 627 | 66.4 | 1054 | 14.8 | 1229 | 42.2 | 521 | 9.7 | 189 | 52.5 | 1678 | 19.9 | ||||

| Community participation | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.842 | |||||||||||||

| No information of such events | 172 | 18.2 | 857 | 12.1 | 440 | 15.1 | 605 | 11.3 | 46 | 13.0 | 1065 | 12.6 | ||||

| None | 665 | 70.4 | 4566 | 64.5 | 1985 | 68.2 | 3383 | 63.1 | 233 | 65.6 | 5444 | 64.6 | ||||

| Yes | 107 | 11.3 | 1660 | 23.4 | 485 | 16.7 | 1377 | 25.7 | 76 | 21.4 | 1915 | 22.7 | ||||

| Decrease in activity opportunities due to COVID-19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| None | 355 | 38.0 | 3675 | 52.0 | 1141 | 39.4 | 3027 | 56.5 | 116 | 32.3 | 4302 | 51.4 | ||||

| Yes | 579 | 62.0 | 3398 | 48.0 | 1754 | 60.6 | 2327 | 43.5 | 243 | 67.7 | 4073 | 48.6 | ||||

| Decrease in income due to COVID-19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| None | 507 | 56.3 | 4602 | 66.3 | 1662 | 59.3 | 3564 | 68.0 | 174 | 51.0 | 5359 | 65.8 | ||||

| Yes | 394 | 43.7 | 2335 | 33.7 | 1143 | 40.7 | 1677 | 32.0 | 167 | 49.0 | 2789 | 34.2 | ||||

| n = 8966 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distress | Insomnia | Probable PTSD | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | ||

| Gender (ref: male) | |||||||

| 1.33 | 1.13–1.57 | 1.21 | 1.08–1.34 | 1.81 | 1.41–2.32 | ||

| The elderly (ref: none) | |||||||

| 0.90 | 0.76–1.06 | 1.36 | 1.22–1.52 | 1.49 | 1.16–1.90 | ||

| Cohabitant (ref: yes) | |||||||

| 1.07 | 0.88–1.31 | 1.20 | 1.04–1.38 | 1.03 | 0.78–1.37 | ||

| Temporary housing category (ref: public housing) | |||||||

| Prefabricated temporary housing | 0.89 | 0.57–1.39 | 1.00 | 0.73–1.37 | 1.38 | 0.77–2.48 | |

| Rental | 0.78 | 0.57–1.05 | 0.90 | 0.72–1.14 | 0.86 | 0.56–1.34 | |

| Current residence (ref: owned house) | |||||||

| Houses for rent | 1.50 | 1.21–1.87 | 1.15 | 0.99–1.33 | 1.95 | 1.41–2.69 | |

| Public housing | 2.14 | 1.63–2.83 | 1.54 | 1.26–1.88 | 2.41 | 1.62–3.58 | |

| Public housing for disaster | 2.16 | 1.08–4.32 | 1.19 | 0.73–1.93 | 2.75 | 1.23–6.16 | |

| Hospitals and institutions | 0.68 | 0.19–2.43 | 0.63 | 0.29–1.36 | 1.48 | 0.33–6.53 | |

| Other | 1.37 | 0.76–2.48 | 1.52 | 1.04–2.24 | 1.50 | 0.64–3.54 | |

| Change of residential school district (ref: unknown) | |||||||

| None | 0.99 | 0.66–1.50 | 0.89 | 0.66–1.20 | 2.07 | 1.01–4.28 | |

| Yes | 0.93 | 0.63–1.37 | 0.89 | 0.66–1.19 | 1.55 | 0.77–3.14 | |

| Loneliness (ref: none) | 9.08 | 7.71–10.70 | 5.55 | 4.90–6.30 | 3.52 | 2.77–4.49 | |

| Community participation (ref: yes) | |||||||

| No information of such events | 1.84 | 1.36–2.50 | 1.56 | 1.29–1.89 | 0.79 | 0.52–1.20 | |

| None | 1.74 | 1.36–2.22 | 1.53 | 1.34–1.75 | 0.88 | 0.65–1.18 | |

| Decrease in activity opportunities due to COVID-19 (ref: none) | |||||||

| 1.41 | 1.19–1.66 | 1.86 | 1.68–2.07 | 1.80 | 1.40–2.31 | ||

| Decrease in income due to COVID-19 (ref: none) | |||||||

| 1.33 | 1.12–1.57 | 1.43 | 1.28–1.59 | 1.92 | 1.51–2.43 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ide-Okochi, A.; Samiso, T.; Kanamori, Y.; He, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Fujimura, K. Depression, Insomnia, and Probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Survivors of the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake and Related Factors during the Recovery Period Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074403

Ide-Okochi A, Samiso T, Kanamori Y, He M, Sakaguchi M, Fujimura K. Depression, Insomnia, and Probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Survivors of the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake and Related Factors during the Recovery Period Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074403

Chicago/Turabian StyleIde-Okochi, Ayako, Tomonori Samiso, Yumie Kanamori, Mu He, Mika Sakaguchi, and Kazumi Fujimura. 2022. "Depression, Insomnia, and Probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Survivors of the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake and Related Factors during the Recovery Period Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074403