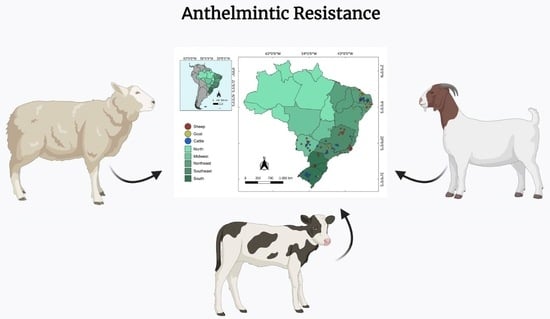

An Overview of Anthelmintic Resistance in Domestic Ruminants in Brazil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

Review Procedures and Map Construction

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anthelmintic Resistance in Small Ruminants

3.2. Anthelmintic Resistance in Cattle

| Region/State | Municipality | Anthelmintics | Number of Animals | Diagnostic Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern | |||||

| RS | NI | ALB, OXF | 16 | FECRT | [37] |

| SC | NI | IVE, LEV, ALB | 2340 | FECRT | [112] |

| RS | São Pedro do Sul | IVE, DOR, ABA, MOX, ALB | 149 | FECRT | [113] |

| RS | Butiá | IVE | 144 | Necropsy | [67] |

| RS | São Martinho da Serra, Dilermando de Aguiar, Cacequi, São Gabriel, Itaqui, São Borja, Santiago and São Vicente do Sul | IVE, DOR, EPR, MOX, LEV, ALB, FEB, CLO, NIT, DIS, ALB + CLO, DOR + CLO | 1704 | FECRT | [114] |

| RS | São Gabriel, São Martinho da Serra and Dilermando de | IVE, DOR, MON, LEV, ALB, CLO | 384 | FECRT | [56] |

| RS | São Gabriel | IVE, DOR, ABA, EPR, MOX | 70 | FECRT | [115] |

| Southeastern | |||||

| SP | NI | IVE | 187 | FECRT | [116] |

| SP | Castilho | MOX | 20 | FECRT | [117] |

| MG | NI | IVE | 24 | Necropsy | [68] |

| MG | Teófilo Otoni | IVE, ALB, ABA, DOR | 84 | FECRT | [118] |

| MG/SP | Candeias, Formiga, Pimenta, Caldas, Prata, Jaboticabal and São José do Rio Pardo | IVE | 144 | Necropsy | [67] |

| MG | NI | IVE, MOX | 40 | FECRT/Necropsy | [69] |

| SP | Jaú, Botucatu and Avaré | IVE | 99 | FECRT | [119] |

| Midwest | |||||

| MS | NI | IVE, MOX | NI | FECRT | [70] |

| MS | Bandeirantes, Campo Grande, Porto Mortinho and Nova Alvorada do Sul | IVE | NI | LMIT | [120] |

| MS | NI | DOR, IVE | 24 | FECRT/Necropsy | [71] |

| MS | Ribas do Rio Pardo | MOX, IVE, ABA, ABA + IVE | 300 | FECRT | [121] |

| Northeastern | |||||

| PB | NI | IVE, ALB, OXF, LEV, TET, CLO, DIS, PYR, MOR | 200 | FECRT | [72] |

| PB | Uiraúna, Aroeira, S. J. Rio do Peixe, Caturité, Barra de Santana, Soledade, Lagoa, Patos, Bom Sucesso, Campina Grande, Santa Cruz, Boa Vista, Gado Bravo, Barra de Santa Rosa, Brejo do Cruz, Joca Claudino, Catolé do Rocha, Belém do Brejo do Cruz, Souza and Aparecida | ALB, IVE, CLO, LEV | 800 | FECRT | [29] |

4. Current Methods for Detection of AR

5. How to Prevent AR Development?

6. Conclusion Remarks and Perspective for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Income, N.; Tongshoob, J.; Taksinoros, S.; Adisakwattana, P.; Rotejanaprasert, C.; Maneekan, P.; Kosoltanapiwat, N. Helminth infections in cattle and goats in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, with focus on strongyle nematode infections. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Vineer, H.R.; Redman, E.; Morosetti, A.; Chen, R.; McFarland, C.; Colwell, D.D.; Morgan, E.R.; Gilleard, J.S. An improved model for the population dynamics of cattle gastrointestinal nematodes on pasture: Parameterisation and field validation for Ostertagia ostertagi and Cooperia oncophora in northern temperate zones. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 310, 109777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagas, A.C.S.; Tupy, O.; Santos, I.B.D.; Esteves, S.N. Economic impact of gastrointestinal nematodes in Morada Nova sheep in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2022, 31, e008722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuir-Baraja, A.E.; Cibot, F.; Llobat, L.; Garijo, M.M. Anthelmintic resistance: Is a solution possible? Exp. Parasitol. 2021, 230, 108169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.D.; Feitosa, T.F.; Vilela, V.L.; Azevedo, S.S.; Almeida Neto, J.L.; Morais, D.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Athayde, A.C. Prevalence and risk factors associated with goat gastrointestinal helminthiasis in the Sertão region of Paraíba State, Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.A.; Bassetto, C.C.; Amarante, M.R.V.; Albuquerque, A.C.A.; Starling, R.Z.C.; Amarante, A.F.T.D. Helminth infections and hybridization between Haemonchus contortus and Haemonchus placei in sheep from Santana do Livramento, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2018, 27, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.B.; Anholeto, L.A.; Sousa, G.A.; Nucci, A.S.; Gainza, Y.A.; Figueiredo, A.; Santos, L.A.L.; Minho, A.P.; Barioni-Junior, W.; Esteves, S.N.; et al. Investigating the benefits of targeted selective treatment according to average daily weight gain against gastrointestinal nematodes in Morada Nova lambs. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flay, K.J.; Hill, F.I.; Muguiro, D.H. A Review: Haemonchus contortus infection in pasture-based sheep production systems, with a focus on the pathogenesis of anaemia and changes in haematological parameters. Animals 2022, 12, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, R.P.; Borges, D.G.; Vieira, M.C.; Conde, M.H.; Green, M.; Amorim, M.L.; Echeverria, J.T.; Oliveira, T.L.; Moro, E.; Van Onselen, V.J.; et al. New approach for the strategic control of gastrointestinal nematodes in grazed beef cattle during the growing phase in central Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 221, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.D.S.S.C.B.; Dias, F.G.S.; Melo, A.L.T.; Carvalho, L.M.; Silva, E.N.; Araújo, J.V. Bioverm® in the control of nematodes in beef cattle raised in the central-west region of Brazil. Pathogens 2021, 10, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisi, L.; Leite, R.C.; Martins, J.R.; Barros, A.T.; Andreotti, R.; Cançado, P.H.; León, A.A.; Pereira, J.B.; Villela, H.S. Reassessment of the potential economic impact of cattle parasites in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2014, 23, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, P.A.; Ruas, J.L.; Riet-Correa, F.; Coelho, A.C.B.; Santos, B.L.; Marcolongo-Pereira, C.; Sallis, E.S.V.; Schild, A.L. Parasitic diseases of cattle and sheep in southern Brazil: Frequency and economic losses estimate. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2017, 37, 797–801. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, G.C.; Jackson, F.; Pomroy, W.E.; Prichard, R.K.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.; Silvestre, A.; Taylor, M.A.; Vercruysse, J. The detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 136, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, R.; Ducray, P.; Jung, M.; Clover, R.; Rufener, L.; Bouvier, J.; Weber, S.S.; Wenger, A.; Wieland-Berghausen, S.; Goebel, T.; et al. A new class of anthelmintics effective against drug-resistant nematodes. Nature 2008, 452, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissiha, W.; Kinde, M.Z. Anthelmintic resistance and its mechanism: A Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 5403–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgsteede, F.H.; Dercksen, D.D.; Huijbers, R. Doramectin and albendazole resistance in sheep in The Netherlands. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 144, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerle, M.C.; Mahling, M.; Pfister, K. Anthelminthic resistance of Haemonchus contortus in small ruminants in Switzerland and Southern Germany. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2009, 121, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurden, T.; Hoste, H.; Jacquiet, P.; Traversa, D.; Sotiraki, S.; Regalbono, A.F.; Tzanidakis, N.; Kostopoulou, D.; Gaillac, C.; Privat, S.; et al. Anthelmintic resistance and multidrug resistance in sheep gastro-intestinal nematodes in France, Greece and Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 201, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattaa, A.F.; Lindberg, A.L. Managing anthelmintic resistance in small ruminant livestock of resource-poor farmers in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2006, 77, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsotetsi, A.M.; Njiro, S.; Katsande, T.C.; Moyo, G.; Baloyi, F.; Mpofu, J. Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminths and anthelmintic resistance on small-scale farms in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2013, 45, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, M.; Tsotetsi-Khambule, A.M.; Moerane, R.; Mashiloane, M.L.; Thekisoe, O.M.M. Risk factors associated with occurrence of anthelmintic resistance in sheep of resource-poor farmers in Limpopo province, South Africa. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019, 51, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialch, A.; Vatsya, S.; Kumar, R.R. Detection of benzimidazole resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep and goats of sub-Himalyan region of northern India using different tests. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 198, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.R.; Begum, N.; Anisuzzaman; Alim, M.A.; Alam, M.Z. Multiple anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants in Bangladesh. Parasitol. Int. 2020, 77, 102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waghorn, T.S.; Leathwick, D.M.; Rhodes, A.P.; Lawrence, K.E.; Jackson, R.; Pomroy, W.E.; West, D.M.; Moffat, J.R. Prevalence of anthelmintic resistance on sheep farms in New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 2006, 6, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyndal-Murphy, M.; Ehrlich, W.K.; Mayer, D.G. Anthelmintic resistance in ovine gastrointestinal nematodes in inland southern Queensland. Aust. Vet. J. 2014, 92, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Playford, M.C.; Smith, A.N.; Love, S.; Besier, R.B.; Kluver, P.; Bailey, J.N. Prevalence and severity of anthelmintic resistance in ovine gastrointestinal nematodes in Australia (2009–2012). Aust. Vet. J. 2014, 12, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, S.B.; Burke, J.M.; Miller, J.E.; Terrill, T.H.; Valencia, E.; Williams, M.J.; Williamson, L.H.; Zajac, A.M.; Kaplan, R.M. Prevalence of anthelmintic resistance on sheep and goat farms in the southeastern United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 233, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falzon, L.C.; Menzies, P.I.; Shakya, K.P.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Vanleeuwen, J.; Avula, J.; Stewart, H.; Jansen, J.T.; Taylor, M.A.; Learmount, J.; et al. Anthelmintic resistance in sheep flocks in Ontario, Canada. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 193, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, L.R.B.; Sousa, L.C.; Menezes, C.S.O.; Alvares, F.B.V.; Ferreira, L.C.; Bezerra, R.A.; Athayde, A.C.R.; Feitosa, T.F.; Vilela, V.L.R. Resistance of bovine gastrointestinal nematodes to four classes of anthelmintics in the semiarid region of Paraíba state, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30, e010921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.S.; Evaristo, A.M.C.F.; Oliveira, G.M.B.; Ferreira, M.S.; Silva, D.L.R.; Azevedo, S.S.; Yamamoto, S.M.; Araújo, M.M.; Horta, M.C. Anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in sheep grazing in irrigated and dry areas in the semiarid region of northeastern Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M. Drug resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance: A status report. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 10, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Vidyashankar, A.N. An inconvenient truth: Global warming and anthelmintic resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 186, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.T.; Gonçalves, P.C. Verificação de estirpe resistente de Haemonchus resistente ao thiabendazole no Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil). Rev. FZVA 1967, 9, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria, F.A.M.; Trindade, G.N.P. Anthelmintic resistance by Haemonchus contortus to ivermectin in Brazil: A preliminary report. Vet. Rec. 1989, 124, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.S.; Gonçalves, P.C.; Costa, C.A.F.; Berne, M.E.A. Redução e esterilização de ovos de nematódeos gastrintestinais em caprinos medicados com anti-helmínticos benzimidazóis. Pesq. Agrop. Bras. 1989, 24, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, T.P.; Pompeu, J.; Miranda, D.B. Efficacy of three broad-spectrum anthelmintics against gastrointestinal nematode infections of goats. Vet. Parasitol. 1989, 34, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, A.C.; Echevarria, F.A.M. Susceptibility of Haemonchus spp. in cattle to anthelmintic treatment with Albendazole and Oxfendazole. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 1990, 10, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, J.A.; Santos, C.P. Overview of anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, L.H.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A. Status of benzimidazole resistance in intestinal nematode populations of livestock in Brazil: A systematic review. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denwood, M.J.; Kaplan, R.M.; McKendrick, I.J.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Nielsen, M.K.; Levecke, B. A statistical framework for calculating prospective sample sizes and classifying efficacy results for faecal egg count reduction tests in ruminants, horses and swine. Vet. Parasitol. 2023, 314, 109867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, M.A.M.; Costa, U.C.; Benevenga, S. Trichostrongylus colubriformis resistente ao levamisole. Rev. Cent. Cienc. Rur. Univ. Fed. St. Maria 1977, 7, 421–422. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, M.A.M.; Costa, U.C.; Benevenga, S.F. Haemonchus contortus e Ostertagia circumcincta resistente ao levamisole. Rev. Cent. Ciênc. Rurais Univ. Fed. St. Maria 1979, 9, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, M.A.M.; Costa, U.C. Resistência de Haemonchus contortus, Trichostrongylus colubriformis, Trichostrongylus colubriformis e Ostertagia spp., ao levamisole. Rev. Cent. Ciênc. Rurais Univ. Fed. St. Maria 1979, 9, 9315–9318. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, M.A.M.; Costa, U.C.; Benevenga, S.F.; Macedo, N. Resistência de Haemonchus contortus à rafoxanida, em ovinos. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 1982, 17, 1361–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria, F.; Pinheiro, A.C. Evaluation of anthelmintic resistance in sheep flocks in the municipality of Bagé. Rio Grande do Sul. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 1989, 9, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria, F.; Borba, M.F.S.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Waller, P.J.; Hansen, J.W. The prevalence of anthelmintic resistance in nematode parasites of sheep in Southern Latin America: Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 1996, 62, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaz-Soccol, V.T.; Sotomaior, C.; Souza, F.P.; Castro, E.A.; Silva, M.C.P.; Milczewski, V. Occurrence of resistance to anthelmintics in sheep in Parana State, Brazil. Vet. Rec. 1996, 139, 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, M.T.; Brodin, E.L.; Forbes, A.B.; Newcomb, K. A survey on resistance to anthelmintics in sheep stud farms of southern Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 1997, 72, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Souza, F.P.; Sotomaior, C.; Castro, E.A.; Milczewski, V.; Mocelin, G.; Silva, M.C.P. Resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes to anthelmintics in sheep (Ovis aries). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2004, 47, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.I.; Bellato, V.; Ávila, V.S.; Coutinho, G.C.; Souza, A.P. Gastro-intestinal parasites resistance in sheep to some anthelmintics in Santa Catarina state, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2002, 32, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, L.F.C.F.; Toledo, G.S.; Grecco, F.C.A.R.; Guerra, J.L. Eficácia da associação closantel albendazol e ivermectina 3,5 no controle da helmintose de ovinos da Região Norte do Estado do Paraná. UNOPAR Cient. Ciênc. Biol. Saud. 2008, 10, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Klauck, V.; Pazinato, R.; Lopes, L.S.; Cucco, D.C.; Lima, H.L.; Volpato, A.; Radavelli, W.M.; Stefani, L.C.M.; Silva, A.S.D. Trichostrongylus and Haemonchus anthelmintic resistance in naturally infected sheep from southern Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2014, 86, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra, M.C.; Teixeira, V.N.; Nascimento, L.V.; Sotomaior, C.S. Lack of efficacy of monepantel against Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 216, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T.; Costa, R.T.; Mendonça, G.; Vaz, R.Z. Eficácia anti-helmíntica comparativa do nitroxinil, levamisol, closantel, moxidectina e fenbendazole no controle parasitário em ovinos. Bol. Ind. Anim. 2017, 74, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.A.; Riet-Correa, B.; Estima-Silva, P.; Coelho, A.C.B.; Santos, B.L.D.; Costa, M.A.P.; Ruas, J.L.; Schild, A.L. Multiple anthelmintic resistance in Southern Brazil sheep flocks. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 26, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, F.; Portella, L.P.; Rodrigues, F.D.S.; Reginato, C.Z.; Cezar, A.S.; Sangioni, L.A.; Vogel, F.S. Anthelminthic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in sheep to monepantel treatment in central region of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2018, 38, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.; Marques, C.B.; Reginato, C.Z.; Bräunig, P.; Osmari, V.; Fernandes, F.; Sangioni, L.A.; Vogel, F.S.F. Field and molecular evaluation of anthelmintic resistance of nematode populations from cattle and sheep naturally infected pastured on mixed grazing areas at Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Acta Parasitol. 2020, 65, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante, A.F.T.; Barbosa, M.A.; Oliveira, M.A.G.; Carmello, M.J.; Padovanni, C.R. Efeito da administração de oxfendazol, ivermectina e levamisol sobre os exames coproparasitológicos de ovinos. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 1992, 29, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, W.B.; Panegossi, M.F.C.; Bresciani, K.D.S.; Gomes, J.F.; Kaneto, C.N.; Perri, S.H.V. Resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes to five different active principles in sheep infected naturally in São Paulo State, Brazil. Small Rumin. Res. 2019, 172, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.F.; Oliveira, L.L.D.S.; Silva, F.V.E.; Lima, W.D.S.; Pereira, C.A.J.; Rocha, R.H.F.; Santos, I.S.; Dias Júnior, J.A.; Alves, C.A. Anthelmintic resistance in sheep in the semiarid region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2023, 37, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.S.; Berne, M.E.A.; Cavalcante, A.C.R.; Costa, C.A.F. Haemonchus contortus resistance to ivermectin and netobimin in Brazilian sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 1992, 45, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.R.; Vilela, V.L.; Feitosa, T.F.; Almeida Neto, J.L.; Morais, D.F. Resistência anti-helmíntica em pequenos ruminantes do semiárido da Paraíba, Brasil. Arq. Vet. 2013, 29, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Bezerra, H.M.F.F.; Feitosa, T.F.; Vilela, V.L.R. Nematode resistance to five anthelmintic classes in naturally infected sheep herds in Northeastern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2018, 27, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahid, S.M.M.; Cavalcante, M.D.A.; Bezerra, A.C.D.; Soares, H.S.; Pereira, R.H.M. Eficácia anti-helmíntica em rebanho caprino no Estado de Alagoas, Brasil. Acta Vet. Bras. 2007, 1, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, A.C.S.; Vieira, L.S.; Aragão, W.R.; Navarro, A.M.C.; Villela, L.C.V. Anthelmintic action of eprinomectin in lactating Anglo-Nubian goats in Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 100, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, W.C.; Athayde, A.C.; Medeiros, G.R.; Lima, D.A.; Borburema, J.B.; Santos, E.M.; Vilela, V.L.R.; Azevedo, S.S. Nematóides resistentes a alguns anti-helmínticos em rebanhos caprinos no Cariri Paraibano. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2010, 30, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felippelli, G.; Lopes, W.D.; Cruz, B.C.; Teixeira, W.F.; Maciel, W.G.; Fávero, F.C.; Buzzulini, C.; Sakamoto, C.; Soares, V.E.; Gomes, L.V.; et al. Nematode resistance to ivermectin (630 and 700 μg/kg) in cattle from the Southeast and South of Brazil. Parasitol. Int. 2014, 63, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, W.D.; Santos, T.R.; Borges, F.A.; Sakamoto, C.A.; Soares, V.E.; Costa, G.H.; Camargo, G.; Pulga, M.E.; Bhushan, C.; Costa, A.J. Anthelmintic efficacy of oral trichlorfon solution against ivermectin resistant nematode strains in cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 166, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, W.D.; Teixeira, W.F.; Felippelli, G.; Cruz, B.C.; Maciel, W.G.; Soares, V.E.; Santos, T.R.; Matos, L.V.; Fávero, F.C.; Costa, A.J. Assessing resistance of ivermectin and moxidectin against nematodes in cattle naturally infected using three different methodologies. Res. Vet. Sci. 2014, 96, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliz, D.C. Anthelmintic Resistance of Gastrointestinal Nematodes in Beef Cattle in the Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil; Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul: Campo Grande, Brazil, 2011; 51p. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, F.A.; Borges, D.G.; Heckler, R.P.; Neves, J.P.; Lopes, F.G.; Onizuka, M.K. Multispecies resistance of cattle gastrointestinal nematodes to long-acting avermectin formulations in Mato Grosso do Sul. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, W.W.; Delfino, L.J.B.; Medeiros, M.C.; Silva, J.P. Multiple resistances of gastrointestinal nematodes to anthelmintic groups in cattle of semiarid of Paraíba, Brazil. Act. Vet. Bras. 2017, 1, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiel, C.A.; Saumell, C.A.; Steffan, P.E.; Rodriguez, E.M. Resistance of Cooperia to ivermectin treatments in grazing cattle of the Humid Pampa, Argentina. Vet. Parasitol. 2001, 97, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, L.F.C.F.; Pereira, A.B.L.; Yamamura, M.H. Resistência a anti-helmínticos em ovinos da região de Londrina-Paraná-Brasil. Semin. Cien. Agrárias 1998, 19, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalinski-Moraes, F.; Moretto, L.H.; Bresolin, W.S.; Gabrielli, I.; Kafer, L.; Zanchet, I.K.; Sonaglio, F.; Thomaz-Soccol, V. Resistência anti-helmíntica em rebanhos ovinos da região da associação dos municípios do alto Irani (AMAI), Oeste de Santa Catarina. Cienc. Anim. Bras. 2007, 8, 559–565. [Google Scholar]

- Cezar, A.S.; Toscan, G.; Camillo, G.; Sangioni, L.A.; Ribas, H.O.; Vogel, F.S. Multiple resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes to nine different drugs in a sheep flock in southern Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 173, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzulini, C.; Silva, A.G.S.S.; Costa, A.J.; Santos, T.R.; Borges, F.A.; Soares, V.E. Eficácia anti-helmíntica comparativa da associação albendazole, levamisole e ivermectina à moxidectina em ovinos. Pesq. Agrop. Bras. 2007, 42, 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.A.; Garcia, K.C.; Torgerson, P.R.; Amarante, A.F. Multiple resistance to anthelmintics by Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep in Brazil. Parasitol. Int. 2010, 59, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.G.; Rocha, L.O.; Arruda, S.S.; Palieraqui, J.G.; Cordeiro, R.C.; Santos, E., Jr.; Molento, M.B.; Santos, C.P. Anthelmintic efficacy and management practices in sheep farms from the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 170, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, E.R.; Silva, R.B.; Vasconcelos, V.O.; Nogueira, F.A.; Oliveira, N.J.F. Diagnóstico do controle e perfil de sensibilidade de nematódeos de ovinos ao albendazol e ao levamisol no norte de Minas Gerais. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2012, 32, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, C.J.; Niciura, S.C.; Alberti, A.L.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Barbosa, C.M.; Chiebao, D.P.; Cardoso, D.; Silva, G.S.; Pereira, J.R.; Margatho, L.F.; et al. Multidrug and multispecies resistance in sheep flocks from São Paulo state, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichuette, M.A.; Lopes, W.D.Z.; Gomes, L.V.C.; Felippelli, G.; Cruz, B.C.; Maciel, W.G.; Teixeira, W.F.P.; Buzzulini, C.; Prando, L.; Soares, V.V.E.; et al. Susceptibility of helminth species parasites of sheep and goats to different chemical compounds in Brazil. Small Rum. Res. 2015, 133, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainza, Y.A.; Santos, I.B.D.; Figueiredo, A.; Santos, L.A.L.D.; Esteves, S.N.; Barioni-Junior, W.; Minho, A.P.; Chagas, A.C.S. Anthelmintic resistance of Haemonchus contortus from sheep flocks in Brazil: Concordance of in vivo and in vitro (RESISTA-Test©) methods. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30, e025120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.V.G.; Silva, Y.H.; Martins, I.V.F.; Scott, F.B. Resistance of Haemonchus contortus to monepantel in sheep: First report in Espírito Santo, Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2021, 30, e013121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sczesny-Moraes, E.A.; Bianchin, I.; Silva, K.F.D.; Catto, J.B.; Honer, M.R.; Paiva, F. Resistência anti-helmíntica de nematóides gastrintestinais em ovinos, Mato Grosso do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2010, 30, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.C.F.L.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L.; Selaive, A.V.; Girão, M.D. Anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes from sheep and goats, in Pentecoste county, State of Ceará. Cienc. Anim. Bras. 1998, 8, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, A.C.F.L.; Reis, I.S.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L.; Vieira, L.S.; Echevarria, F.A.M.; Melo, L.M. Nematódeos resistentes a anti-helmíntico em rebanhos de ovinos e caprinos do estado do Ceará, Brasil. Cienc. Rural 2003, 33, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.C.F.L.; Rondon, F.C.M.; Reis, I.S.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L. Desenvolvimento da resistência ao oxfendazol em propriedades rurais de ovinos na região do Baixo e Médio Jaguaribe, Ceará, Brasil. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 13, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.H.M.A.; Ahid, S.M.M.; Bezerra, A.C.D.S.; Soares, H.S.; Fonseca, Z.A.A.S. Diagnosis of nematodes gastrintestinal resistance to antihelminthic in goats and sheep from Rio Grande do Norte state, Brazil. Acta Vet. Bras. 2008, 2, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, M.M.D.; Farias, M.P.O.; Romeiro, E.T.; Ferreira, D.R.A.; Alves, L.C.; Faustino, M.A.D.G. Eficácia da moxidectina, ivermectina e albendazole contra helmintos gastrintestinais em propriedades de criação caprina e ovina no estado de Pernambuco. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2010, 11, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Filho, J.V.; Ribeiro, W.L.C.; André, W.P.P.; Cavalcante, G.S.; Santos, J.M.L.; Monteiro, J.P.; Macedo, I.T.F.; Oliveira, L.M.B.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L. Phenotypic and genotypic approaches for detection of anthelmintic resistant sheep gastrointestinal nematodes from Brazilian northeast. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2021, 30, e005021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.J.T.D.; Schmidt, V.; Bastos, C.D. Atividade ovicida de dois fármacos em caprinos naturalmente parasitados por nematódeos gastrintestinais, RS, Brasil. Ciênc. Rural 2000, 30, 893–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.J.T.; Oliveira, C.M.B.M.; Gouveam, A.S.; Andrade, C.B. Macrocyclic lactone-resistant strains of Haemonchus in naturally infected goats. Cienc. Rural 2004, 34, 883–884. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Bier, D.; Fortes, F.S.; Warzensaky, P.; Bainy, A.M.; Macedo, A.A.S.; Molento, M.B. Avaliação do sistema integrado de controle parasitário em uma criação semi-intensiva de caprinos na região de Santa Catarina. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2012, 64, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra, M.C.R.; Teixeira, V.N.; Nascimento, L.V.; Ollhoff, R.D.; Sotomaior, C.S. Monepantel resistant Trichostrongylus colubriformis in goats in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2018, 11, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.S.; Cavalcante, A.C.R. Resistência anti-helmíntica em rebanhos caprinos no Estado do Ceará. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 1999, 19, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.B.; Athayde, A.C.R.; Rodrigues, O.G. Silva WW, Faria EB. Sensibilidade dos nematóides gastrintestinais de caprinos a anti-helmínticos na mesorregião do Sertão Paraibano. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2007, 27, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, W.A.C.; Ahid, S.M.M.; Vieira, L.S.; Fonseca, Z.A.A.S.; Silva, I.P. Resistência anti-helmíntica em caprinos no município de Mossoró, RN. Cienc. Anim. Bras. 2010, 11, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.L.D.S.O.; Athayde, A.C.R.; Olinto, F.A. Sensibilidade dos nematóides gastrintestinais de caprinos leiteiros à anti-helmínticos no Município de Sumé, Paraíba, Brasil. Agrop. Cient. Semiárido 2010, 9, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, S.L.; Oliveira, A.A.; Mendonça, L.R.; Lambert, S.M.; Viana, J.M.; Nishi, S.M.; Julião, F.S.; Almeida, M.A.O. Resistência anti-helmíntica em rebanhos caprinos nos biomas Caatinga e Mata Atlântica. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2015, 35, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.M.S.; Souza, E.A.R.; Dantas, A.C.S.; Silva, I.W.G.; Araújo, M.M.; Azevedo, S.S.; Sangioni, L.A.; Horta, M.C. Parasitic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats from the semiarid region of Pernambuco, Northeastern Brazil. Vet. Zootec. 2021, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.M. Biology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of livestock. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2020, 36, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Ahmad, A.A.; Li, X.; Du, A.; Hu, M. Recent research progress in china on Haemonchus contortus. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, A.C.A.; Basseto, C.C.; Almeida, F.A.; Amarante, A.F.T. Development of Haemonchus contortus resistance in sheep under suppressive or targeted selective treatment with monepantel. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 246, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenyon, F.; Jackson, F. Targeted flock/herd and individual ruminant treatment approaches. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 186, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.; Pomroy, B.; Paul, K.; Greg, S.; Barbara, A.; Moss, A. Lack of efficacy of monepantel against Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus colubriformis. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 198, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederos, A.E.; Ramos, Z.; Banchero, G.E. First report of monepantel Haemonchus contortus resistance on sheep farms in Uruguay. Parasit. Vectors. 2014, 7, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niciura, S.C.M.; Cruvinel, G.G.; Moraes, C.V.; Chagas, A.C.S.; Esteves, S.N.; Benavides, M.V.; Amarante, A.F.T. In vivo selection for Haemonchus contortus resistance to monepantel. J. Helminthol. 2020, 94, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbarre, L.C. Anthelmintic resistance in cattle nematodes in the US. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 204, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leathwick, D.M.; Luo, D. Managing anthelmintic resistance—Variability in the dose of drug reaching the target worms influences selection for resistance? Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 243, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiak, B.H.B.; Lehnen, C.B.; Rocha, R.A. Anthelmintic resistance of injectable macrocyclic lactones in cattle: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.P.D.; Ramos, C.I.; Bellato, V.; Sartor, A.A.; Schelbauer, C.A. Resistência de helmintos gastrintestinais de bovinos a anti-helmínticos no Planalto Catarinense. Ciênc. Rural 2008, 38, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cezar, A.S.; Vogel, F.S.; Sangioni, L.A.; Antonello, A.M.; Camillo, G.; Toscan, G.; Araujo, L.O.D. Ação anti-helmíntica de diferentes formulações de lactonas macrocíclicas em cepas resistentes de nematódeos de bovinos. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2010, 30, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.; Portella, L.P.; Rodrigues, F.S.; Reginato, C.Z.; Pötter, L.; Cezar, A.S.; Sangioni, L.A.; Vogel, F.S.F. Anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of beef cattle in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2016, 6, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivoto, F.L.; Cezar, A.S.; Vogel, F.S.F.; Leal, M.L.D.R. Effects of long-term indiscriminate use of macrocyclic lactones in cattle: Parasite resistance, clinical helminthosis, and production losses. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2020, 20, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutello, R.G.V.; Seno, M.C.Z.; Amarante, A.F.T. Anthelmintic resistance in cattle nematodes in northwestern São Paulo State, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 148, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condi, G.K.; Soutello, R.G.; Amarante, A.F. Moxidectin-resistant nematodes in cattle in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 61, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.S.V.L.F.; Araújo, R.N.; Costa, A.J.L.F.D.; Simões, R.F.; Lima, W.D.S. Anthelmintic resistance in a dairy cattle farm in the State of Minas Gerais. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2011, 20, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.H.; Carvalho, N.; Rinaldi, L.; Cringoli, G.; Amarante, A.F. Diagnosis of anthelmintic resistance in cattle in Brazil: A comparison of different methodologies. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 206, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, G.D.; Feliz, D.C.; Heckler, R.P.; Borges, D.G.; Onizuka, M.K.; Tavares, L.E.; Paiva, F.; Borges, F.A. Ivermectin and moxidectin resistance characterization by larval migration inhibition test in field isolates of Cooperia spp. in beef cattle, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2013, 191, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, D.G.L.; Conde, M.H.; Cunha, C.C.T.; Freitas, M.G.; Moro, E.; Borges, F.A. Moxidectin: A viable alternative for the control of ivermectin-resistant gastrointestinal nematodes in beef cattle. Acta Vet. 2022, 72, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.R.; Lopes, W.D.Z.; Buzulini, C.; Borges, F.A.; Sakamoto, C.A.M.; Lima, R.C.A.; Oliveira, G.P.; Costa, A.J. Helminth fauna of bovines from the Central-Western region, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2010, 40, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, G.C.; Stafford, K.A.; Mackay, P.H.S. Ivermectin-resistant Cooperia species from calves on a farm in Somerset. Vet. Rec. 1998, 7, 255–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, L.A.E.; Arellano, M.E.L.; Gives, P.M.; Hernandez, E.L.; Prats, V.V.; Ycuspinera, G.V. First report in Mexico on ivermectin resistance on naturally infected calves with gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet. Mex. 2008, 39, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Demeler, J.; Van Zeveren, A.M.J.; Kleinschmidt, N.; Vercruysse, J.; Höglund, J.; Koopmann, R.; Cabaret, J.; Claerebout, E.; Areskog, M.; Von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. Monitoring the efficacy of ivermectin and albendazole against gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle in Northern Europe. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 160, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasbarre, L.C.; Smith, L.L.; Lichtenfels, J.R.; Pilitt, P.A. The identification of cattle nematode parasites resistant to multiple class of anthelmintics in a commercial cattle population in the US. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 166, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, B.E.; Gasbarre, L.C.; Waite, A.; Bechtol, D.T.; Brown, M.S.; Robinson, N.A.; Olson, E.J.; Newcomb, H. Cooperia punctata: Effect on cattle productivity? Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 183, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyndal-Murphy, M.; Rogers, D.; Ehrlich, W.K.; James, P.J.; Pepper, P.M. Reduced efficacy of macrocyclic lactone treatments in controlling gastrointestinal nematode infections of weaner dairy calves in subtropical eastern Australia. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 168, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendell, D.K. Anthelmintic resistance in cattle nematodes on 13 south-west Victorian properties. Aust. Vet. J. 2010, 88, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvandini, H.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Gennari, S.M.; McManus, C.M.; Vitti, D.M.S.S. Phosphorus kinetics in calves experimentally submitted to a trickle infection with Cooperia punctata. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 163, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, G.C.; Bauer, C.; Borgsteede, F.H.; Geerts, S.; Klei, T.R.; Taylor, M.A.; Waller, P.J. World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) methods for the detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet. Parasitol. 1992, 44, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.J.; Anderson, N.; Jarrett, R.G. Detecting benzimidazole resistance with faecal egg count reduction tests and in vitro assays. Aust. Vet. J. 1989, 66, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Denwood, M.J.; Nielsen, M.K.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Torgerson, P.R.; Gilleard, J.S.; Dobson, R.J.; Vercruysse, J.; Levecke, B. World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) guideline for diagnosing anthelmintic resistance using the faecal egg count reduction test in ruminants, horses and swine. Vet. Parasitol. 2023, 318, 109936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.V.; Coles, G.C.; Jackson, F.; Bauer, C.; Borgsteede, F.; Cirak, V.Y.; Demeler, J.; Donnan, A.; Dorny, P.; Epe, C.; et al. Standardization of the egg hatch test for the detection of benzimidazole resistance in parasitic nematodes. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K. What makes a good fecal egg count technique? Vet. Parasitol. 2021, 296, 109509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cringoli, G.; Rinaldi, L.; Maurelli, M.P.; Utzinger, J. FLOTAC: New multivalent techniques for qualitative and quantitative copromicroscopic diagnosis of parasites in animals and humans. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cringoli, G.; Maurelli, M.P.; Levecke, B.; Bosco, A.; Vercruysse, J.; Utzinger, J.; Rinaldi, L. The Mini-FLOTAC technique for the diagnosis of helminth and protozoan infections in humans and animals. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotze, A.C.; Gilleard, J.S.; Doyle, S.R.; Prichard, R.K. Challenges and opportunities for the adoption of molecular diagnostics for anthelmintic resistance. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2020, 14, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, J.H.; Carlson, S.A.; Jones, D.E.; Brewer, M.T. Molecular mechanisms for anthelmintic resistance in strongyle nematode parasites of veterinary importance. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 40, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, A.; Humbert, J.F. A molecular tool for species identification and benzimidazole resistance diagnosis in larval communities of small ruminant parasites. Exp. Parasitol. 2000, 95, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niciura, S.C.; Veríssimo, C.J.; Gromboni, J.G.; Rocha, M.I.; Mello, S.S.; Barbosa, C.M.; Chiebao, D.P.; Cardoso, D.; Silva, G.S.; Otsuk, I.P.; et al. F200Y polymorphism in the β-tubulin gene in field isolates of Haemonchus contortus and risk factors of sheep flock management practices related to anthelmintic resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 190, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, A.M.; Sampaio Junior, F.D.; Pacheco, A.; Cunha, A.B.; Cruz, J.S.; Scofield, A.; Góes-Cavalcante, G. F200Y polymorphism of the β-tubulin isotype 1 gene in Haemonchus contortus and sheep flock management practices related to anthelmintic resistance in eastern Amazon. Vet Parasitol. 2016, 226, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.M.; Nishi, S.M.; Mendonça, L.R.; Souza, B.M.P.S.; Julião, F.S.; Gusmão, P.S.; Almeida, M.A.O. Genotypic profile of benzimidazole resistance associated with SNP F167Y and F200Y beta-tubulin gene in Brazilian populations of Haemonchus contortus of goats. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2017, 8, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, W.; Zaman, M.A.; Faheem, M.; Ahmed, I.; Ali, K.; Qamar, M.F.; Ishaq, H.M.; Atif, F.A. Molecular confirmation and genetic characterization of Haemonchus contortus isolate at the nuclear ribosomal ITS2 region: First update from Jhang region of Pakistan. Pak. Vet. J. 2022, 42, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Airs, P.M.; Ventura-Cordero, J.; Mvula, W.; Takahashi, T.; Van Wyk, J.; Nalivata, P.; Safalaoh, A.; Morgan, E.R. Low-cost molecular methods to characterize gastrointestinal nematode co-infections of goats in Africa. Parasite Vectors 2023, 16, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramenko, R.W.; Redman, E.M.; Lewis, R.; Yazwinski, T.A.; Wasmuth, J.D.; Gilleard, J.S. Exploring the gastrointestinal "Nemabiome": Deep amplicon sequencing to quantify the species composition of parasitic nematode communities. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramenko, R.W.; Redman, E.M.; Melville, L.; Bartley, Y.; Wit, J.; Queiroz, C.; Bartley, D.J.; Gilleard, J.S. Deep amplicon sequencing as a powerful new tool to screen for sequence polymorphisms associated with anthelmintic resistance in parasitic nematode populations. Int. J. Parasitol. 2019, 49, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperiale, F.; Lanusse, C. The Pattern of blood-milk exchange for antiparasitic drugs in dairy ruminants. Animals 2021, 11, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, S.F.D.; Schreiner, L.L.; Silva, I.P.; Franco, R.M. Residues of veterinary drugs in milk in Brazil. Ciênc. Rural 2017, 47, e20170215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, J.M.; Costa, R.G.; Araújo, A.C.P.; Albuquerque, E.C.; Cunha, A.N.; Cruz, G.R.B.D. Determining anthelmintic residues in goat milk in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Saúde Prod. Anim. 2019, 20, e04102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.O.; Cerqueira, A.P.M.; Branco, A.; Batatinha, M.J.M.; Botura, M.B. Anthelmintic activity of plants against gastrointestinal nematodes of goats: A review. Parasitology 2019, 146, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, D.; Richards, K.G.; Danaher, M.; Grant, J.; Gill, L.; Mellander, P.E.; Coxon, C.E. An analysis of the spatio-temporal occurrence of anthelmintic veterinary drug residues in groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 69, 144804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.F.; Costa Junior, L.M.; Lima, A.S.; Silva, C.R.; Ribeiro, M.N.; Mesquista, J.W.; Rocha, C.Q.; Tangerina, M.M.; Vilegas, W. Anthelmintic activity of plant extracts from Brazilian savanna. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 236, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Espinoza, M.; Boas, U.; Williams, A.R.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Simonsen, H.T.; Enemark, H.R. Sesquiterpeno lactona contendo extratos de duas cultivares de chicória forrageira (Cichorium intybus) mostram perfis químicos distintos e atividade in vitro contra Ostertagia ostertagi. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2015, 5, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klongsiriwet, C.; Quijada, J.; Williams, A.R.; Mueller-Harvey, I.; Williamson, E.M.; Hoste, H. Synergistic inhibition of Haemonchus contortus exsheathment by flavonoid monomers and condensed tannins. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2015, 5, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiba, A.R.; Kagira, J.M.; Ngotho, M.; Kimotho, J.; Maina, N. In vitro anthelmintic efficacy of nano-encapsulated bromelain against gastrointestinal nematodes of goats in Kenya. World’s Vet. J. 2022, 12, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, M.; Akhtar, T.; Zaheer, T.; Ahmad, S.; Ashraf, U.; Omar, M. Anti-parasitic Applications of Nanoparticles: A Review. Pak. Vet. J. 2022, 42, 2074–7764. [Google Scholar]

- Wasso, S.; Maina, N.; Kagira, J. Toxicity and anthelmintic efficacy of chitosan encapsulated bromelain against gastrointestinal strongyles in Small East African goats in Kenya. Vet. World 2020, 13, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, K.A.; Chishti, M.Z.; Ahmad, F.; Shawl, A.S. Anthelmintic efficacy of Achillea millifolium against gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Helminthol. 2008, 82, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, D.G.L.; Borges, F.A. Plants and their medicinal potential for controlling gastrointestinal nematodes in ruminants. Nematoda 2016, 3, e92016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, I.; Wani, Z.A.; Shahardar, R.A.; Allaie, I.M.; Shah, M.M. Integrated parasite management with special reference to gastro-intestinal nematodes. J. Parasit. Dis. 2017, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leathwick, D.M.; Besier, R.B. The management of anthelmintic resistance in grazing ruminants in Australasia—Strategies and experiences. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 204, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zvinorova, P.I.; Halimani, T.E.; Muchadeyi, F.C.; Matika, O.; Riggio, V.; Dzama, K. Breeding for resistance to gastrointestinal nematodes—The potential in low-input/output small ruminant production systems. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 225, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, T.G.; Sakanari, J.A.; Caffrey, C.R. Anthelmintic drug discovery: Into the future. J. Parasitol. 2015, 101, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, H.A. Anthelmintics Resistance; How to Overcome it? Iran J. Parasitol. 2013, 8, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

| Region/State | Municipality | Anthelmintics | Number of Animals | Diagnostic Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern | |||||

| RS | NI | THI | 308 | FECRT | [34] |

| NI | NI | LEV | NI | NI | [41] |

| NI | NI | LEV | NI | NI | [42] |

| NI | NI | LEV | 6 | Necropsy | [43] |

| RS | Uruguaina | RAF | 9 | FECRT | [44] |

| RS | Bagé | ALB, LEV | NI | FECRT | [45] |

| RS | Bagé | IVE | 89 | FECRT | [34] |

| RS | NI | ALB, LEV, IVE, CLO, ALB + LEV | NI | FECRT | [46] |

| PR | NI | ALB, CLO, LEV, FEB, IVE, TET, DIS + TET | 480 | FECRT | [47] |

| RS | NI | LEV, ALB, FEB, OXF, MEB | 870 | FECRT | [48] |

| PR | Cambé, Tamarana and Londrina | IVE, ALB, MOX | 850 | FECRT | [74] |

| PR | NI | OXF, IVE, CLO, CLO + OXF, LEV, MOX | NI | FECRT | [49] |

| SC | NI | IVE, LEV, CLO, ALB | 7529 | FECRT | [50] |

| SC | Passos Maia, Vargeão, Ponte Serrada, Faxinal dos Guedes, Xanxere and Xaxim | IVE, ALB, MOX, CLO, LEV | 450 | FECRT | [75] |

| PR | NI | CLO + ALB, IVE | 120 | FECRT | [51] |

| RS | NI | LEV, MON, ALB, IVE, NIT, DIS, TRI, CLO, IVE + LEV + ALB | 500 | FECRT | [76] |

| SC | NI | CLO, LEV, ALB, ALB + LEV | 135 | FECRT | [52] |

| PR | NI | MON | 50 | FECRT/CT | [53] |

| RS | NI | MOX, FEB | 78 | FECRT | [54] |

| RS | NI | ABA, ALB, CLO, LEV, MON, TRI | 1540 | FECRT | [55] |

| RS | São Pedro do Sul, São Gabriel and São Martinho da Serra | MON | NI | FECRT | [56] |

| RS | São Gabriel, São Martinho da Serra, Dilermando de | IVE, DOR, MON, LEV, ALB, CLO | 366 | FECRT | [57] |

| Aguiar, Bagé, Capão do Cipó, São Francisco de Assis and Santa Maria | |||||

| Southeastern | |||||

| SP | São Manuel | OXF, IVE, LEV | 540 | FECRT | [58] |

| SP | Jaboticabal | MOX | 24 | FECRT | [77] |

| SP | Pratânia | ALB, LEV, MOX, IVE, TRI, CLO | 42 | FECRT | [78] |

| RJ | Campos dos Goytacazes, Cardoso Moreira, Quissamã, São Francisco de Itabapoana, Santo Antonio de Pádua and São João da Barra | ALB, CLO, DIS, FEB, IVE, MON, NIT | 770 | FECRT | [79] |

| MG | Montes Claros, Bocaiúva, Janaúba, Pirapora, Francisco Sá, Coração de Jesus and Januária | ALB | 252 | FECRT | [80] |

| SP | NI | ALB, CLO, IVE, LEV, MON | 1617 | FECRT | [81] |

| SP | Jaboticabal, Viradouro, Pontal, Morro Agudo, Sertãozinho, Ribeirão Preto, Taquaritinga and São João da Boa Vista | IVE, MOX | 160 | Necropsy | [82] |

| SP | Araçatuba | ALB, LEV, IVE, MON, CLO, IVE + LEV + ALB | 350 | FECRT | [59] |

| SP | NI | ALB, LEV, IVE, MON, THI | 245 | FECRT/LDT | [83] |

| ES | Alegre | MON | 20 | FECRT/Necropsy | [84] |

| MG | NI | ALB, IVE, LEV | 381 | FECRT | [60] |

| Midwest | |||||

| MS | Angélica, Camapuã, Campo Grande, Corumbá, Coxim, Ivinhema, Miranda, Porto Murtinho, Ribas do Rio Pardo, São Gabriel do Oeste, Sidrolândia, Terenos, Camapuã, Campo Grande, Miranda and Porto Murtinho | ALB, CLO, IVE, LEV, MOX, TRI, ALB + IVE + LEV | 120 | FECRT | [85] |

| Northeastern | |||||

| CE | Sobral | NET, IVE | 20 | FECRT | [61] |

| CE | Pentecoste | CLO, OXF | 38 | FECRT | [86] |

| CE | Limoeiro do Norte, Palhano, Jaguaruana, Itaiçaba, Aracati, Alto Santo, Morada Nova and Jaguaribe | OXF, LEV, IVE | 768 | FECRT | [87] |

| CE | Limoeiro do Norte, Aracati e Jaguaribe | OXF | 144 | FECRT | [88] |

| RN | NI | ALB, IVE | 54 | FECRT | [89] |

| PE | Recife, Vitória de Santo Antão and Garanhuns | ALB | NI | FECRT | [90] |

| PB | Gado Bravo | IVE, LEV | 234 | FECRT | [62] |

| PB | Aparecida, Marizópolis, Patos, Souza, São José da Lagoa Tapada, São josé de Piranhas and São José do Rio do Peixe | ALB, IVE, CLO, LEV, MON | 600 | FECRT | [63] |

| CE | Caucaia | ALB, IVE, LEV | 74 | EHT, FECRT/LDT/qPCR | [91] |

| Region/State | Municipality | Anthelmintics | Number of Animals | Diagnostic Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern | |||||

| RS | Gravataí | CLO, LEV | 40 | FECRT | [92] |

| RS | Porto Alegre | IVE | 12 | FECRT | [93] |

| SC | São Francisco do Sul | ALB, ABA, CLO, NIT, LEV, MOX, IVE, IVER + LEV + ALB | 63 | FECRT | [94] |

| PR | NI | MOX | 45 | FECRT | [95] |

| Southeastern | |||||

| SP | Jaboticabal, Viradouro, Pontal, Morro Agudo, Sertãozinho, Ribeirão Preto, Taquaritinga and São João da Boa Vista | IVE, MOX | 160 | Necropsy | [82] |

| Northeastern | |||||

| CE | Sobral | OXF, FEB, ALB, THI | 25 | FECRT | [35] |

| CE | Pentecoste | IVE, CLO | 29 | FECRT | [87] |

| CE | NI | OXF, LEV | 1020 | FECRT | [96] |

| CE | Limoeiro do Norte, Palhano, Jaguaruana, Itaiçaba, Aracati, Alto Santo, Morada Nova and Jaguaribe | OXF, LEV, IVE | 336 | FECRT | [88] |

| AL | Mar Vermelho | IVE, ALB | 40 | FECRT | [64] |

| CE | Sobral | EPR | 24 | FECRT | [65] |

| PB | NI | ALB, IVE | 120 | FECRT | [97] |

| RN | NI | ALB, IVE | 54 | FECRT | [89] |

| RN | Mossoró | ALB, IVE | 1350 | FECRT | [98] |

| PB | Monteiro | ALB, IVE, LEV | 264 | FECRT | [66] |

| PE | Sertânia, Paudalho, Camocim de São Félix and Taquaritinga do Norte | ALB, IVE | NI | FECRT | [90] |

| PB | Gado Bravo | IVE | 270 | FECRT | [62] |

| PB | Sumé | ALB | 40 | FECRT | [99] |

| BA | Santa Inês, Cravolândia and Ubaíra | ALB, IVE, LEV, MOX, CLO | 360 | FECRT | [100] |

| PE | Petrolina | ALB, IVE, LEV, MOX, CLO | 420 | FECRT | [101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macedo, L.O.; Silva, S.S.; Alves, L.C.; Carvalho, G.A.; Ramos, R.A.N. An Overview of Anthelmintic Resistance in Domestic Ruminants in Brazil. Ruminants 2023, 3, 214-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants3030020

Macedo LO, Silva SS, Alves LC, Carvalho GA, Ramos RAN. An Overview of Anthelmintic Resistance in Domestic Ruminants in Brazil. Ruminants. 2023; 3(3):214-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants3030020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacedo, Lucia Oliveira, Samuel Souza Silva, Leucio Câmara Alves, Gílcia Aparecida Carvalho, and Rafael Antonio Nascimento Ramos. 2023. "An Overview of Anthelmintic Resistance in Domestic Ruminants in Brazil" Ruminants 3, no. 3: 214-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants3030020