1. Introduction

The relationship between emotion and social organization has been a topic of interest in anthropology since Durkheim’s emphasis on sentiments in the constitution of society [

1]. Recent decades have seen anthropologists focus on emotion as an independent area of study, exploring questions about the universality of basic emotions and the cross-cultural validity of Western psychological categories [

2,

3]. Studies have revealed that emotions are intertwined with culture, language, and social life, challenging the idea of a distinct emotional domain included in the dimension of individual experience [

4]. They have refined distinctions and explored applications of emotions in various contexts, shedding light on different aspects of social life, including market activity [

5], political struggle [

6], and social sufferance [

7], topics which were previously scantly explored [

8]. In so doing, they addressed questions about the intersection of emotions with social life.

This chapter explores a concept developed in the framework of this debate, the “affective economy”, aimed at shedding light on the interactions between individuals, communities, their activities, and their environment. While this term was introduced into the current debate of social sciences through the work of Ahmed [

9], over the years, it has seen various uses and interpretations, which this entry describes. In particular, through the analysis of this concept, in these pages, I will attempt to provide a comprehensive account of the different ways in which affects enter the social space influencing the actions and the understanding of individuals and communities.

Before beginning this analysis, it will be useful to clarify the semantic perimeter of two key terms that will be widely used in this entry, emotions (and affections) and affects, since their meanings have been widely debated and pose challenges, often being used as synonyms in common speech. In this entry, the words emotions (and affections) and affects have distinct meanings. Here, building on an established understanding of emotions in anthropology, emotions are understood as culturally bounded dimensions of experience that may differ from culture to culture or from community to community [

10]. Specifically, “emotions are presumed to be a form of social construction […while affects are] the force that moves bodies of all kinds […] into and out of states of being. Affect is not ontologically distinct from or secondary to cognition or meaning.” [

11]. In the following pages, I will specify the meanings assigned to the words, when unclear or overlapping, to offer the most accessible the discussion and easy understanding of the cultural process at stake.

This entry opens by introducing the cultural context in which the concept of affective economy was introduced, thus delving into its original formulation and foundation to indicate some of the areas of research where it has been used. Thus, it explores some of the limitations this theoretical tool presents, indicating a possible integration of the different interpretations given to affective economy to make it possible for this concept to encompass the entire process through which affects turn into emotions and then into cultural objects that circulate within and transform society. To clarify the theoretical contribution of this concept and its heuristic use, this entry closes with an example of an application to explore the current consumption practices linked with diamonds.

This entry is the result of a narrative literary review conducted on scientific publications related to the social sciences [

12]. Detailed information can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

2. The Context

A common image of what an economy is revolves around the exchange of labor, capital, and goods, as if it were something governed by sheer rationality and detached from any aspect concerning the culture and place where the action takes place [

13]. This understanding underpins a rhetoric built on an idealized universal idea of humanity, portrayed by the

homo economicus: an individual free from any constraints, making every economic choice based on rational decision making, aiming for efficiency and profit maximization [

14].

Social sciences, and specifically economic anthropology [

15], have repeatedly highlighted the limits of this implicit tenet of economic understanding and neoclassical economics. For example, during the 1950s and 1960s, the debate between formalists and substantivists in anthropology questioned the limits of economic universalism, drawing attention to the moral, ethical, and social specificities of each community as fundamental dimensions shaping economic processes [

16]. More recently, during the 1990s and early 2000s, the rekindled debate concerning the spirit of the gift indicated the complexity of motivations that lead and govern and form of economic exchange [

17]. Overall, as explained by Karl Polanyi, the economy, rather than being a domain separated from the life of the community, is embedded in it, and its forms respond to its needs, beliefs, and expectations [

18]. In the economic crisis of 2007–2008 [

19] and subsequent years, the debate on embeddedness gained renewed vigor, and embeddedness emerged as a category to discuss the limits and dynamics of new financial processes and instruments [

20] and a direction for delving with greater attention into the analysis of local dynamics. Completing this reflection that reconnects economy to place and people, behavioral economics and neuroeconomics, which are the recent disciplines that explore the interface between economics, psychology, and neuroscience to empirically study human behaviors, emphasized the centrality of emotions, contingencies, and the specificity of individual intellectual processes in shaping economic actions [

21,

22]. Considering this prominent debate that embraces the social sciences, the limitations of a rationalistic and universalistic description of the economy appear starkly requiring of new theoretical tools and approaches to analyze and describe the dynamics that unfold with an economic transaction. In this regard, this entry focuses on the concept of affective economy as a tool to investigate the cultural interconnectedness that links communities and places to economies and is expressed through affects, which are the experiential, emotional, and embodied dimensions of human interactions and experiences of the surrounding.

3. The Concept

While the term “affective economy” had already been introduced in the 1970s to study the role of non-rational factors in economic decision making [

23], the concept was established in the academic debate thanks to Ahmed and her “The Cultural Politics of Emotion” [

9]. Ahmed offered her contribution in a period when the debate in social sciences had started questioning the main assumptions of neoclassical theory and, in particular, the idea of the market as a reality separated from and untouched by the socio-cultural context in which action takes place. Different from Michel Callon, Yuval Millo, and Fabian Muniesa [

24], and the other scholars inspired by the Actor–Network Theory who dominated the scene [

25,

26,

27,

28] and explored the tools on which modern markets are based, from the composition of financial indices to the structure of stock exchange operations, demonstrating the social relevance and impact of these instruments, Ahmed explores the role of emotions as a type of social infrastructure of political and economic actions [

29].

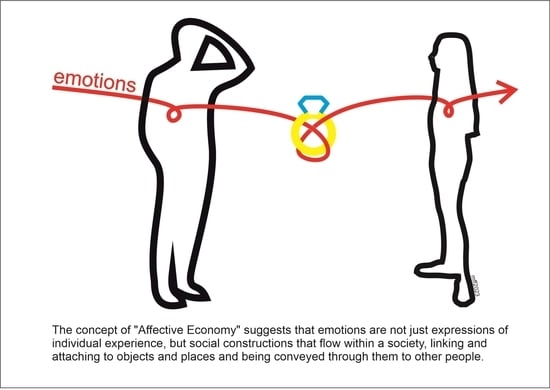

Ahmed introduces the concept of “affective economies” to describe how emotions enter the public life of society as objects that circulate and contribute to the construction and maintenance of the social order, particularly concerning gender, race, and sexuality. She points out that an affective economy implies that emotions do not exclusively reside within any individual or entity. Instead, ‘the subject’ merely serves as a single point within a network of exchanges, rather than being its source or destination. This holds significance, as it indicates that emotions like hate, with their sideways and backward shifts, are not confined to a subject’s boundaries. Consequently, the unconscious is not the unconscious of an individual, but rather the deficiency of presence, or the inability to be present, which shapes the interconnectedness of subjects, objects, signs, and others. In light of this, affective economies encompass social, material, and psychological dimensions [

9]. In Ahmed’s terms, emotions are not merely individual and private experiences but are social facts that enable individuals and communities in their actions, economic practices included. Thus, they work as part of and respond to the socio-political structure in which the individual is embedded.

The nuanced account provided by Ahmed highlights how emotions should be considered for the inter- and super-subjective role that makes them not only part of the economic reality but also a building element of the socialized space. This approach follows a heuristic tradition consolidated by the works of Yi-Fu Tuan. In this respect, Tuan’s “Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values” [

30] and, subsequently, “Landscape of Fear” [

31] explored the complex relationship between people and their environments and demonstrated that affects, such as fear, are not just an irrational reaction to external circumstances, such as the presence of immediate threats, but rather social and cultural constructs influenced by historical, cultural, and societal factors, specifically through physical and cultural interactions and people’s relationship with their surroundings. Echoing Tuan’s work, the contribution of Ahmed [

9] describes the process of the social construction of affections and sheds light on how the emotions “stick” to surfaces and bodies, affecting the activities that involve them once one interacts with them. From this perspective, in recent years, Ahmed’s work has formed the basis of a stream of studies that, as indicated by Elaine Lynn-Ee Ho [

32], investigates how social identities are scripted in and by space [

33,

34], how one’s emotional wellbeing can be enhanced through the affective atmosphere of specific places [

35,

36], or how emotions can intersect with and shape mobility [

37,

38]. Similarly, the concept has been used to explore economic facts and their signification within a certain community or social group [

39,

40,

41].

The concept of affective economy has been utilized as an analytical instrument within qualitative research. It has become associated with the analysis of data originating from in-depth interviews and focus groups, as well as observation or participant observation. Specifically, these studies investigated, on the one hand, the intricate web of relationships and meanings that interconnect objects (both tangible and intangible), places, and actions with narratives related to and prompting specific emotions. On the other, they explored how a narrative of specific emotions becomes intertwined with a network of objects, places, and actions. This qualitative approach has functioned to communicate and emphasize the open and fluid nature of this web of relationships, albeit at the expense of extensive quantitative and large-scale studies.

4. Further Developments

Despite the success of this concept as a heuristic key for social analysis, scholars have pointed towards some limitations of its original formulation. In particular, as Analiese Richard and Daromir Rudnyckyj [

39] highlighted, in Ahmed’s work, all the economies of affects appear as “closed, self-regulating circuits” in which affections are pre-defined, circulating entities. This understanding, where emotions are essentialized into neatly defined, universal pseudo-objects [

42], appears incapable of fully describing the creative, generative, and open-ended dimension of culture and of a social space. In response to this, based on distinct ethnographic case studies, they proposed considering affections as a cultural medium through which interactions and economic actions are negotiated. Moreover, in the ethnographies of Richard and Rudnyckyi, affects are not (pre-)defined objects circulating in each environment, but rather the results of a grassroots process of symbolic interaction among the members of a community that give shape to affections. In this respect, the works of Kathleen Stewart further this line of reasoning [

43]. Stewart suggests the fulcrum of an affective economy should be affects and not emotions. Following Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari [

44], the anthropologist suggests that affects permeate the social field in which the subject and community operate, constituting the affective atmosphere in which they are immerged [

45] and that has an effect on their actions and ways of understanding the world, as indicated by Ben Anderson [

46]. In this process, individuals and communities relate with the affects and make sense of them; through the interaction between the atmospheric and the personal, emotions are recognized and defined on the basis of the cultural categories shared by individuals and their communities [

11]. At the same time, the individuals make sense of and relate to the environment in which they live, and the activities that occur therein, including those considered to be of economic pertinence. Following Steward, although with a different lexicon, affective economies are not only about the social life of emotions, using the famous definition by Arjun Appadurai [

47], but are also about dwellings. Tim Ingold [

48,

49,

50] has repeatedly stressed how dwelling represents an immersive relational dimension through which the individual and the community interface with their surroundings. If, for Ingold, this form of being-in-the-world can be expressed through the concept meshwork, a dynamic and interconnected web of relationships between humans and their environment, emphasizing active and ongoing engagement with the world [

51], Nicola Perullo expands this concept and emphasizes that dwelling is the dynamic result of multiple correspondences established between all the elements of an environment [

52]; affects and emotions are manifestations of this relationship and its individual and communitarian understanding. Although this reflection apparently moves away from the economic reality and embraces an existential perspective, following it, affective economies can be understood as an individual and collective exercise of becoming aware of, discussing, and shaping this inter-objective interconnectivity. In this case, a new set of questions arises about why economic objects and actions can better attract attention and kindle a collective reflection, thus opening a window for further ethnographic research concerning the hierarchies of value of the communities.

5. An Application: Diamonds and Love

An example would be useful in clarifying the different levels of analysis. In so doing, I will borrow from my ongoing research on jewelry making that began over a decade ago in Italy [

53]. In particular, I focus on one key object in the international jewelry imagination and market: diamonds.

A diamond is a precious gemstone known for its exceptional brilliance, hardness, and beauty. It is composed of carbon atoms arranged in a crystal cubic structure that gives it the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any natural material. Typically, diamonds are transparent or translucent, though the presence of impurities (i.e., the presence of traces of other elements, such as boron and nitrogen, within the articulate) tints them with different shades of colors such as blue, yellow, brown [

54]. Despite the recent development of artificial diamonds [

55], the bulk of diamonds in the market are natural and excavated from deposits located in Angola, Australia, Canada, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Russia, South Africa, Zimbabwe.

If the history of the diamond industry has been widely studied as a key example of the employment of anti-competitive business practices aimed at creating artificial scarcity [

56], for the sake of this entry, they are relevant for their strict correlation with emotion. Since the 1930s, when De Beers, the world’s largest diamond company, sought to promote the consumption of diamonds in the expanding American market, businesses have launched an imposing advertising campaign linking the use of diamonds to love and marriage [

57]. The motto: a diamond is forever [

58]. The campaign had success in creating a strong association between the commodity and the emotion that reverberates globally in the present. Without entering the market dynamics and taking for granted the strength of this association, the lens of the affective economy sheds light on different social dynamics that interconnect the precious stone with affects and emotions.

The first level is the most evident one: the one that links an emotion, love, and a ritual, that of engagement and marriage, to a specific gemstone in an intense and significant association. In recent decades, this association has proved so strong that it has naturalized into a consumption practice and become a standard driver of diamond consumption [

58]. However, with the increasing uncertainty linked with the duration of marriages, this association is proving particularly limiting for the current diamond market. While millennials and younger generations increasingly perceive marriage as an uncertain terrain, they are increasingly shying away from diamonds, preferring different materials and objects to communicate affection [

59]. In this sense, as social customs and practices transform and the meaning of a codified emotion is questioned, consumption practices also change, transforming the market.

This first level of analysis, which is closely associable with Ahmed’s and is widely explored in marketing and business administration studies, opens further questions concerning the ways in which consumers create an association between what they feel and the objects around them. During my fieldwork, investigating the motivation behind the purchase of a solitaire or a trilogy ring, among younger consumers (under 30) in Italy, it was common to hear very diverse answers that spanned from “it is a must” to “she asked for it” and “it does not represent what I am and what I feel”. This variety highlights the plurality of sources which the consumer draws on in defining their own choice: from direct experiences to the media, examples among peers, and previous generations. As suggested by Daniel Miller [

60], through this comparison, as well as the analysis of the material possibilities, the consumer has to access particular goods, as well as the relationship with the other person who receives the object, and an individual path of signification is forged, associating objects with emotions and vice versa. Emotions, on the other hand, are not inherently codified and can take on nuances of meaning tied to the specific community of reference, one’s religion, and ethics. Hence the necessity of ethnographic analysis.

In the face of this, a further level of inquiry opens. This interrogates the motivations that lead, for example, to the need to purchase and donate an object to express emotion, for example, the “invisible forces” that permeate society and shape its political and economic structure, as Nigel Thrift pointed out [

61]. These forces are the affects indicated by Steward, and their study allows us to better understand the specificities of the affective atmosphere in which individuals live and that defines the social field in which they move.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

The chapter presented the concept of the affective economy, its foundation, and critiques. This concept is a powerful heuristic tool for exploring the cultural process through which communities make sense of their environment, their (economic) activities, and their communal life. In this regard, it focuses on the cultural meanings, expectations, and social role played by and underpinning all economic actions, as well as their relationships with a given community and place, rather than the econometric results of these very activities. If the formulation of this theoretical concept was carried out in a moment of discussion about the limits of neoclassical economic theory and, in particular, the limits of utilitarian rationality, at the same time, it helps us to engage in reflections concerning the social role and social life of emotions in each community and in a given period of time.

The concept of the affective economy, introduced by Ahmed, challenged the notion of emotions as isolated individual experiences and highlighted their deep entanglement with social, cultural, and political contexts. In this respect, the debate around the affective economy suggests three main levels on which analysis can be conducted, as the example of diamond markets also indicates. First, emotions, as cultural objects, circulate within a given community, affecting its life, as in Ahmed’s work. Then, this affects how emotions are identified and defined, because of a rationalization and subjective communitarian expression of these relations, as explained by Richard and Rudnyckyi. Then, one can explore how affects, as atmospheric forces, act on the bodies, for example, in shaping their direction, intensity, and strength, and how bodies relate to affects in an emerging correlation identified through the language of emotions, as suggested by Stewart. Far from being mutually exclusive, these three levels are interconnected and mutually reinforce each other, defining the cultural and social horizon in which the life of an individual and their community develops.

Considering the potentialities offered by the affective economy for the analysis of an economy, this concept leads researchers to question and delve into the contextual reality in which economic actions take place. Above all, it guides the researcher to explore the meanings attributed to objects, places, and actions that are part of an economic transaction and how these meanings play an infrastructural role in the economy.

Thus, despite the limitations of its original formulation, this concept appears to be an interesting tool to add to the methodological tool kit of contemporary research, enabling us to unravel the socio-cultural dynamics underlying the multifaceted relationships between individuals, communities, and their surroundings, as well as the emergence and impacts of affects and emotions.

Looking towards the future, based on the present application of this concept, it is evident, first and foremost, that there is potential to extend its scope of utilization to encompass quantitative studies. In cases where the concept enables the identification of strong correlations between objects and emotions, as elucidated by the example of diamonds, these extensive studies can better delineate and prove the social and cultural biographies of an emotion or an object. Consequently, they can support endeavors in marketing, communication, and product development, aiming to fully enhance the meanings associated with them.

Furthermore, this concept can be employed in studies that can be diachronic, on the one hand, aiming to explore the evolution of meanings attributed to specific objects or emotions over time, and synchronic, on the other hand, aiming to more precisely define the characteristics assumed by these objects and emotions in different communities and places. These studies can create new opportunities for consistent temporal and geographical comparisons, enhancing our overall ethnological understanding of objects, places, actions, and emotions. Not all of these may be useful for calculating the econometric impact of specific economic activities but are crucial for fathoming the cultural basis on which an economy lies.