Financial Interdependence: A Social Perspective

Definition

:1. Introduction

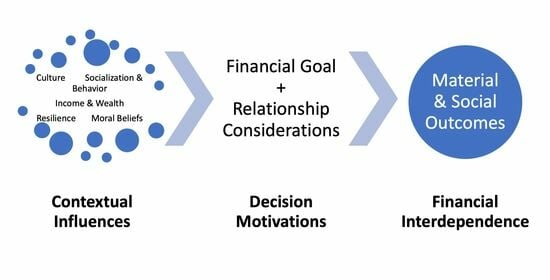

2. Theoretical Frameworks and Themes

2.1. Frameworks

2.1.1. Interdependence Theory

2.1.2. Life Course Theory

2.1.3. Person-in-Environment Perspective

2.1.4. Other Theories and Perspectives

- Social exchange theory [11]: individuals navigate relationships via FI and the associated material and relational costs and benefits;

- Feminist and conflict theories [11]: considerations of dependence and power shape the nature of FI and the extent to which it may lead to equitable and empowering relationships or domination and control;

- Transtheoretical model and stages of change [24]: the emotional development of an individual who starts out with a dependence, either providing or receiving in a manner that is emotionally unhealthy, and moves to a healthy balance of personal responsibility for self and others;

- Experiential learning theory [27]: the practice of FI is either reinforced or diminished based upon the perception of the outcome and if, how, or when it should be conducted in the future;

- Financial capability [28]: the features of FI may present as reasons, ways, and means for achieving financial well-being.

2.2. Culture

2.3. Socialization and Behavior

2.4. Income and Wealth

2.5. Resilience

2.6. Religion, Spirituality, and Moral Principles

3. Applications and Implications

4. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdul Mutalib, A.S.; Dahlan, A.H.; Danis, A. Financial Interdependence among Malay Older People in the Community: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2017, 2, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Why We Need Interdependence Theory. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 2049–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry-McKibbin, R.; Hsiao, C.Y.-L.; Martin, V.L. Measuring Financial Interdependence in Asset Markets with an Application to Eurozone Equities. J. Bank. Financ. 2021, 122, 105985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianca, A. What Is Financial Interdependence? Available online: https://bizfluent.com/info-8615171-financial-interdependence.html (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Bouman, F.J.A. Rosca: On the Origin of the Species/Rosca: Sur L’origine Du Phenomène. Sav. Dev. 1995, 19, 117–148. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Cosío, A. ‘Informal’ Financial Practices in the South Bronx: Family, Compadres, and Acquaintances. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Puppa, F.; Ambrosini, M. ‘Implicit’ Remittances in Family Relationships: The Case of Bangladeshis in Italy and Beyond. Glob. Netw. 2022, 22, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruthi, B.; Watkins, K.; McCoy, M.; Muruthi, J.R.; Kiprono, F.J. “I Feel Happy That I Can Be Useful to Others”: Preliminary Study of East African Women and Their Remittance Behavior. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 38, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, R.A.; Keister, L.A. The Lasting Effect of Intergenerational Wealth Transfers: Human Capital, Family Formation, and Wealth. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 68, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H. Time and Financial Transfers within and beyond the Family. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2006, 27, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.R.; Henderson, A.C. Family Theories: Foundations and Applications; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, E.A.; Gerdes, K.E.; Steiner, S. An Introduction to the Profession of Social Work: Becoming a Change Agent, 6th ed.; Cengage Empowerment Series; Cengage Learning; Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-337-56710-7. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.M.; Olive, P. Financial Coaching: Defining an Emerging Field. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research; Xiao, J.J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-28885-7. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. The Grameen Bank. Sci. Am. 1999, 281, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, S.; (Potawatomi and Odawa of Michigan from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Denver, Colorado, United States). Personal Communication, 2023.

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Health in Old Age: A Scoping Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Norlund, R.D.; Newman-Norlund, S.E.; Sayers, S.; McLain, A.C.; Riccardi, N.; Fridriksson, J. Effects of Social Isolation on Quality of Life in Elderly Adults. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.; McDermott, F. Social Work from inside and between Complex Systems: Perspectives on Person-in-Environment for Today’s Social Work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2010, 40, 2414–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E. Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much; Times Books, Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Friedline, T.; Wood, A.K.; Morrow, S. Financial Education as Political Education: A Framework for Targeting Systems as Sites of Change. J. Community Pract. 2022, 30, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J. Integrating Family Resilience and Family Stress Theory. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, K.F.; Shippee, T.P. Aging and Cumulative Inequality: How Does Inequality Get under the Skin? Gerontologist 2009, 49, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rand, A.M. The Precious and the Precocious: Understanding Cumulative Disadvantage and Cumulative Advantage over the Life Course. Gerontologist 1996, 36, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. The Transtheoretical Approach. In Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration; Norcross, J.C., Goldfried, M.R., Eds.; Oxford Series in Clinical Psychology; Oxford University Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, M.A.; Parrott, E.; Ahn, S.Y.; Serido, J.; Shim, S. Young Adults’ Life Outcomes and Well-Being: Perceived Financial Socialization from Parents, the Romantic Partner, and Young Adults’ Own Financial Behaviors. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2018, 39, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmunson, C.G.; Danes, S.M. Family Financial Socialization: Theory and Critical Review. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2011, 32, 644–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, A.B.; Runyan, S.D.; Jorgensen, B.L.; Marks, L.D.; Li, X.; Hill, E.J. Practice Makes Perfect: Experiential Learning as a Method for Financial Socialization. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherraden, M. Building Blocks of Financial Capability. In Financial Capability and Asset Development: Research, Education, Policy, and Practice; Birkenmaier, J., Sherraden, M., Curley, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- shona264. What Is the Importance of Giving First Salary to Your Parents? Available online: http://www.mylot.com/post/2201127/what-is-the-importance-of-giving-first-salary-to-your-parents (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Pru Life UK Should You Give Your Parents Your First Paycheck? Available online: https://www.prulifeuk.com.ph/en/explore-pulse/health-financial-wellness/should-you-give-your-parents-your-first-paycheck/index.html (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Dang, M. Their Children Are Their Retirement Plans. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/blogs-podcasts-websites/their-children-are-retirement-plans/docview/2767396755/se-2?accountid=28267 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Mangoma, A.; Wilson-Prangley, A. Black Tax: Understanding the Financial Transfers of the Emerging Black Middle Class. Dev. South. Afr. 2019, 36, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, M.; Grier-Reed, T. The Tanda: An Informal Financial Practice at the Intersection of Culture and Financial Management for Mexican American Families. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, M.S. Savings Associations. In Urban Poverty in the Caribbean: French Martinique as a Social Laboratory; Laguerre, M.S., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 1990; pp. 113–140. ISBN 978-1-349-20890-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bilecen, B. ‘Altın Günü’: Migrant Women’s Social Protection Networks. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijia, Z.; Horita, M. Rule Preferences for Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs): Household Surveys from China. Internet J. Soc. Soc. Manag. Syst. 2020, 12, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Morduch, J.; Schneider, R. The Financial Diaries; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Demosthenous, C.; Robertson, B.; Cabraal, A.; Singh, S. Cultural Identity and Financial Literacy: Australian Aboriginal Experiences of Money and Money Management; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman, T.; Charles, B.; Stevens, B.; Wright, B.; John, S.; Ervin, B.; Joe, J.; Ninguelook, G.; Heeringa, K.; Nu, J.; et al. Changes in Sharing and Participation Are Important Predictors of the Health of Traditional Harvest Practices in Indigenous Communities in Alaska. Hum. Ecol. 2022, 50, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, A.B.; Kelley, H.H. Financial Socialization: A Decade in Review. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.J.; Smith, T.E.; Shelton, V.M.; Richards, K.V. Three Interventions for Financial Therapy: Fostering an Examination of Financial Behaviors and Beliefs. J. Financ. Ther. 2015, 6, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeshima, G.; Klontz, B.T. Cognitive-Behavioral Financial Therapy. In Financial Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice; Klontz, B.T., Britt, S.L., Archuleta, K.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Despard, M.R.; Chowa, G. The Role of Parents in Introducing Children to Financial Services: Evidence from Ghana-YouthSave. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 38, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari-Clark, J.; Rose, T. Financial Behavioral Health and Investment Risk Willingness: Implications for the Racial Wealth Gap. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, G.L.; Stylianou, A.M.; Hetling, A.; Postmus, J.L. Developing and Validating the Scale of Economic Self-Efficacy. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 3011–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lown, J.M. Outstanding AFCPE® Conference Paper: Development and Validation of a Financial Self-Efficacy Scale. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2011, 22, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, C. All Our Kin; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, M. Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor. Am. J. Sociol. 2012, 117, 1295–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J.; Ogden, T.; Schneider, R. An Invisible Finance Sector: How Households Use Financial Tools of Their Own Making; U.S. Financial Diaries Project; Financial Access Initiative and Center for Financial Services Innovation: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten, R.; Elder, G.; Pearce, L. Living on the Edge: An American Generation’s Journey through the Twentieth Century; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel, N. Rethinking Families and Community: The Color, Class, and Centrality of Extended Kin Ties. Sociol. Forum 2011, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J.; Siwicki, J. In and out of Poverty: Episodic Poverty and Income Volatility in the US Financial Diaries. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2017, 91, 390–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021; Federal Reserve Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, A.; Rucci, M. The Financial Resilience of Households: 22 Country Study with New Estimates, Breakdowns by Household Characteristics and a Review of Policy Options; Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion—London School of Economics: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, B.; Xiao, J.J. Financial Resiliency before, during, and after the Great Recession: Results of an Online Study. J. Consum. Educ. 2011, 28, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A.; Schneider, D.J.; Tufano, P. Financially Fragile Households: Evidence and Implications; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R. Families under Stress: Adjustment to the Crises of War Separation and Return; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Rosino, M. ABC-X Model of Family Stress and Coping. Wiley Blackwell Encycl. Fam. Stud. 2016, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, K.; Reeve, R.; Connolly, C.; Marjolin, A.; Salignac, F.; Ho, K. Financial Resilience in Australia 2015; Centre for Social Impact (CSI)–University of New South Wales, for National Australia Bank: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, K.; Kumar, S.; Rao, P.; Colombage, S.; Sharma, A. Financial Distress and COVID-19: Evidence from Working Individuals in India. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2021, 13, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.; Xiao, J.J. Refereed Poster: Personal Finance Resiliency Assessment Quiz. In Proceedings of the Eastern Family Economics and Resource Management Association; 2006. Available online: https://www.fermascholar.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/18-personal-finance-resiliency-assessment.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Salignac, F.; Marjolin, A.; Reeve, R.; Muir, K. Conceptualizing and Measuring Financial Resilience: A Multidimensional Framework. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 145, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD/INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/oecd-infe-2020-international-survey-of-adult-financial-literacy.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Nembhard, J.G. Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-271-06426-0. [Google Scholar]

- Huet, T. Can Coops Go Global? Mondragon Is Trying. Available online: https://dollarsandsense.org/archives/1997/1197huet.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Chavunduka, D.M.; Huizer, G.; Khumalo, T.D.; Thede, N. Khuluma Usenza: The Story of O.R.A.P in Zimbabwe’s Rural Development; ORAP: Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- ORAP. Zenzele ORAP Zenzele—The Organisation of Rural Associations for Progress. Available online: https://orapzenzele.org/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Ma’ani, B.R.; Ewing, S.M. Laws of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas; George Ronald: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-85398-476-7. [Google Scholar]

- Otterman, S. 2 New Yorkers Erased $1.5 Million in Medical Debt for Hundreds of Strangers. The New York Times, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, S.D.; Usman, M.; Majid, A.; Lakhan, G.R. Distribution of Wealth an Islamic Perspective: Theoretical Consideration. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 23, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal House of Justice. Letter to the Baha’is of the World. 1 March 2017. Available online: https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/20170301_001/1#712004157 (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Canale, A.; Archuleta, K.L.; Klontz, B.T. Money Disorders. In Financial Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice; Klontz, B.T., Britt, S.L., Archuleta, K.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge, G.L.; Stylianou, A.M.; Postmus, J.L.; Johnson, L. Domestic Violence/Intimate Partner Violence and Issues of Financial Abuse and Control: What Does Financial Empowerment Look Like? In The Routledge Handbook on Financial Social Work: Direct Practice with Vulnerable Populations; Callahan, C., Frey, J.J., Imboden, R., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lample, P. Revelation & Social Reality: Learning to Translate What Is Written into Reality; Palabra Publications: West Palm Beach, FL, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-890101-70-1. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.C.; Burnes, D.P.R.; Caccamise, P.L.; Mason, A.; Henderson, C.R.; Wells, M.T.; Berman, J.; Cook, A.M.; Shukoff, D.; Brownell, P.; et al. Financial Exploitation of Older Adults: A Population-Based Prevalence Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz-Hamilton, A.; Zurlo, K.A. Financial Abuse and Victimization of Older Adults. In The Routledge Handbook on Financial Social Work: Direct Practice with Vulnerable Populations; Callahan, C., Frey, J.J., Imboden, R., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Development Institute, First Nations Oweesta Corporation. Building Native Communities: Financial Skills for Families, 5th ed.; First Nations Development Institute, First Nations Oweesta Corporation: Longmont, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rouf, K. The Impact of the Grameen Bank upon the Patriarchal Family and Community Relations of Women Borrowers in Bangladesh [Doctoral Thesis]; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011; ISBN 0-494-78102-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Spangler, T.L.; Gutter, M.S. Extended Families: Support, Socialization, and Stress. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 45, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anvari-Clark, J.; Miller, J. Financial Interdependence: A Social Perspective. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 996-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030072

Anvari-Clark J, Miller J. Financial Interdependence: A Social Perspective. Encyclopedia. 2023; 3(3):996-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnvari-Clark, Jeffrey, and Julie Miller. 2023. "Financial Interdependence: A Social Perspective" Encyclopedia 3, no. 3: 996-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030072