Sugarcane Straw Polyphenols as Potential Food and Nutraceutical Ingredient

Abstract

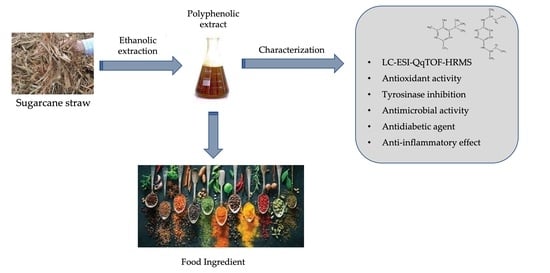

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Byproduct Material

2.3. Extraction and Isolation of Phenolic Compounds from Sugarcane Straw

2.4. Phenolic Compounds and Organic Acid Identification and Quantification by LC-ESI-UHR-QqTOF-MS

2.5. Antioxidant Capacity Evaluation

2.5.1. ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay

2.5.2. DPPH Radical Cation Decolorization Assay

2.6. Minimal Inhibitory and Bactericidal Concentrations Determination

2.7. Inhibition of Tyrosinase Activity Quantification

2.8. Antidiabetic Activity Quantification

2.8.1. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

2.8.2. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) Inhibition Assay

2.9. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

2.10. Caco-2 Monolayer Immunomodulation

2.11. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sugarcane Straw Phenolic Compound Profile

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity

3.4. Effect on Tyrosinase Inhibition

3.5. Antidiabetic Potential

3.6. Influence of Extract on Caco-2 Cell Viability

3.7. Anti-Inflammatory Effect

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, S.E.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, S.; Farag, M.A. More than sweet: A phytochemical and pharmacological review of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.). Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurício Duarte-Almeida, J.; Novoa, A.V.; Linares, A.F.; Lajolo, F.M.; Inés Genovese, M. Antioxidant Activity of Phenolics Compounds From Sugar Cane (Saccharum officinarum L.) Juice. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2006, 61, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.J.; Oliveira, A.L.; Pedrosa, S.S.; Pintado, M.; Madureira, A.R. Potential of sugarcane extracts as cosmetic and skincare ingredients. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 169, 113625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.; Milessi, T.S.; Mulinari, D.R.; Lopes, M.S.; da Costa, S.M.; Candido, R.G. Sugarcane straw as a potential second generation feedstock for biorefinery and white biotechnology applications. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 144, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F. Antioxidants in food and food antioxidants. Food Nahrung 2000, 44, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, N.; Lee, C.H.; Wong, S.L.; Fauzi, C.E.; Zamri, N.M.; Lee, T.H. Prevention of Enzymatic Browning by Natural Extracts and Genome-Editing: A Review on Recent Progress. Molecules 2022, 27, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Fonseca, A.M.A.; Amaro, A.L.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Oliveira, A.; Santos, S.A.O.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Rocha, S.M.; Isidoro, N.; Pintado, M. Natural-based antioxidant extracts as potential mitigators of fruit browning. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corato, U. Improving the shelf-life and quality of fresh and minimally-processed fruits and vegetables for a modern food industry: A comprehensive critical review from the traditional technologies into the most promising advancements. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 940–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Smolen, J.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Combeet, B. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC): Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: A pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 2016, 387, 1513–1530, In this Article, Catherine Pelletier. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, B.; Yan, Y.; Liang, J.; Guan, X. Bound Polyphenols from Red Quinoa Prevailed over Free Polyphenols in Reducing Postprandial Blood Glucose Rises by Inhibiting α-Glucosidase Activity and Starch Digestion. Nutrients 2022, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Inoue, T.; Yasuda, N.; Sato, Y.; Nagakura, T.; Takenaka, O.; Clark, R.; Saeki, T.; Tanaka, I. Comparison of Efficacies of a Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Inhibitor and α-Glucosidase Inhibitors in Oral Carbohydrate and Meal Tolerance Tests and the Effects of Their Combination in Mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 104, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, W.; Mats, L.; Liu, R.; Deng, Z.; Tsao, R. Anti-Inflammatory Effect and Cellular Transport Mechanism of Phenolics from Common Bean (Phaseolus vulga L.) Milk and Yogurts in Caco-2 Mono- and Caco-2/EA.hy926 Co-Culture Models. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldes, A.B.; Vecino, X.; Cruz, J.M. Nutraceuticals and Food Additives; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 9780444636775. [Google Scholar]

- Augustin, M.A.; Sanguansri, L. Challenges in Developing Delivery Systems for Food Additives, Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, B.; Falco, V.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Bacelar, E.; Peixoto, F.; Correia, C. Effects of Elevated CO2 on Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): Volatile Composition, Phenolic Content, and in Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Red Wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.A.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Costa, E.M.; Fernandes, J.C.; Tavaria, F.K.; Araruna, F.B.; Eiras, C.; Eaton, P.; Leite, J.R.S.A.; Manuela Pintado, M. Study of antimicrobial activity and atomic force microscopy imaging of the action mechanism of cashew tree gum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-I.; Apostolidis, E.; Shetty, K. In vitro studies of eggplant (Solanum melongena) phenolics as inhibitors of key enzymes relevant for type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 2981–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/36406.html (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Costa, E.M.; Pereira, C.F.; Ribeiro, A.A.; Casanova, F.; Freixo, R.; Pintado, M.; Ramos, O.L. Characterization and Evaluation of Commercial Carboxymethyl Cellulose Potential as an Active Ingredient for Cosmetics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Costa, E.M.; Silva, S.; Rodriguez-Alcalá, L.M.; Gomes, A.M.; Pintado, M. Pomegranate Oil’s Potential as an Anti-Obesity Ingredient. Molecules 2022, 27, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, I.D.; Baker, J.M.; Ward, J.L.; Beale, M.H.; Creste, S.; Cavalheiro, A.J. Metabolite Profiling of Sugarcane Genotypes and Identification of Flavonoid Glycosides and Phenolic Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4198–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deseo, M.A.; Elkins, A.; Rochfort, S.; Kitchen, B. Antioxidant activity and polyphenol composition of sugarcane molasses extract. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Su, S.; Zhou, H.; Yan, H.; Ye, J.; Zhao, Z.; You, L.; Fu, X. Antioxidant/antihyperglycemic activity of phenolics from sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) bagasse and identification by UHPLC-HR-TOFMS. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 101, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.; Granell, P.; Tárraga, S.; López-Gresa, P.; Conejero, V.; Bellés, J.M.; Rodrigo, I.; Lisón, P. Salicylic acid and gentisic acid induce RNA silencing-related genes and plant resistance to RNA pathogens. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechchate, H.; Es-safi, I.; Al Kamaly, O.M.; Bousta, D. Insight into Gentisic Acid Antidiabetic Potential Using In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Molecules 2021, 26, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimani, B.G.; Kerekes, E.B.; Szebenyi, C.; Krisch, J.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Papp, T.; Takó, M. In Vitro Activity of Selected Phenolic Compounds against Planktonic and Biofilm Cells of Food-Contaminating Yeasts. Foods 2021, 10, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyota, E.; Mazzafera, P.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F. Analysis of Soluble Lignin in Sugarcane by Ultrahigh Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry with a Do-It-Yourself Oligomer Database. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 7015–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilani-Jaziri, S.; Mokdad-Bzeouich, I.; Krifa, M.; Nasr, N.; Ghedira, K.; Chekir-Ghedira, L. Immunomodulatory and cellular anti-oxidant activities of caffeic, ferulic, and p-coumaric phenolic acids: A structure–activity relationship study. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 40, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajko, E.; Kalinowska, M.; Borowski, P.; Siergiejczyk, L.; Lewandowski, W. 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid: A spectroscopic study and biological screening for antimicrobial activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, D.J.; Wurms, K.V.; Labbé, C.; Bélanger, R.R. Synthesis of C-glycosyl flavonoid phytoalexins as a site-specific response to fungal penetration in cucumber. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003, 63, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulas, V.; Papoti, V.T.; Exarchou, V.; Tsimidou, M.Z.; Gerothanassis, I.P. Contribution of Flavonoids to the Overall Radical Scavenging Activity of Olive (Olea europaea L.) Leaf Polar Extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3303–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeff, J.; Joubert, J.; Malan, S.F.; van Dyk, S. Antioxidant properties of 4-quinolones and structurally related flavones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kaur, M.; Silakari, O. Flavones: An important scaffold for medicinal chemistry. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 84, 206–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, K.; Kurokawa, M.; Obuchi, M.; Li, Y.; Yamada, R.; Sadanari, H.; Matsubara, K.; Watanabe, K.; Koketsu, M.; Tuchida, Y.; et al. Anti-Influenza Virus Activity of Tricin, 4′,5,7-trihydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxyflavone. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2011, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, G.G.; Gao, S.; Lee, J.K.; Chan, Y.-Y.; Wong, E.C.; Zheng, T.; Li, X.-X.; Shaw, P.-C.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Lau, C.B. A Natural Flavone Tricin from Grains Can Alleviate Tumor Growth and Lung Metastasis in Colorectal Tumor Mice. Molecules 2020, 25, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, T.; Yasui, Y.; Sugie, S.; Koketsu, M.; Watanabe, K.; Tanaka, T. Dietary tricin suppresses inflammation-related colon carcinogenesis in male Crj: CD-1 mice. Cancer Prev. Res. 2009, 2, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.; Imm, J.Y. Antiobesity Effect of Tricin, a Methylated Cereal Flavone, in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obese Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 9989–9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Yang, X.; Flavel, M.; Shields, Z.P.-I.; Kitchen, B. Antioxidant and Anti-Diabetic Functions of a Polyphenol-Rich Sugarcane Extract. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauberte, L.; Telysheva, G.; Cravotto, G.; Andersone, A.; Janceva, S.; Dizhbite, T.; Arshanitsa, A.; Jurkjane, V.; Vevere, L.; Grillo, G.; et al. Lignin—Derived antioxidants as value-added products obtained under cavitation treatments of the wheat straw processing for sugar production. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 126369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.-F.; Cha, K.H.; Lee, E.H.; Pan, C.-H.; Um, B.-H. Optimization, bio accessibility of tricin and anti-oxidative activity of extract from black bamboo leaves. Free Radic. Antioxid. 2016, 6, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Chen, S.G.; Yue, G.G.L.; Kwok, H.F.; Lee, J.K.M.; Zheng, T.; Shaw, P.C.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Lau, C.B.S. Natural flavone tricin exerted anti-inflammatory activity in macrophage via NF-κB pathway and ameliorated acute colitis in mice. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalini, V.; Jayalekshmi, A.; Helen, A. Mechanism of anti-inflammatory effect of tricin, a flavonoid isolated from Njavara rice bran in LPS induced hPBMCs and carrageenan induced rats. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 66, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solyanik, G.I.; Zulphigarov, O.S.; Prokhorova, I.V.; Pyaskovskaya, O.N.; Kolesnik, D.L.; Atamanyuk, V.P. A Comparative Study on Pharmacokinetics of Tricin, a Flavone from Gramineous Plants with Antiviral Activity. J. Biosci. Med. 2021, 09, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołosiak, R.; Drużyńska, B.; Derewiaka, D.; Piecyk, M.; Majewska, E.; Ciecierska, M.; Worobiej, E.; Pakosz, P. Verification of the Conditions for Determination of Antioxidant Activity by ABTS and DPPH Assays—A Practical Approach. Molecules 2022, 27, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Lu, B. Phytochemical contents and antioxidant capacities of different parts of two sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) cultivars. Food Chem. 2014, 151, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Flavel, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, O.C.Y.; Downey, L.; Stough, C.; Kitchen, B. A polyphenol rich sugarcane extract as a modulator for inflammation and neurological disorders. PharmaNutrition 2020, 12, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, U.S.; Ghosh, S.B.; De, S.; Suprasanna, P.; Devasagayam, T.P.A.; Bapat, V.A. Antioxidant activity in sugarcane juice and its protective role against radiation induced DNA damage. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Costa, E.M.; Costa, M.R.; Pereira, M.F.; Pereira, J.O.; Soares, J.C.; Pintado, M.M. Aqueous extracts of Vaccinium corymbosum as inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus. Food Control 2015, 51, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin-Karaca, H.; Newman, M.C. Antimicrobial efficacy of plant phenolic compounds against Salmonella and Escherichia Coli. Food Biosci. 2015, 11, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, S. The antibiotic activity and mechanisms of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) bagasse extract against food-borne pathogens. Food Chem. 2015, 185, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Georgescu, C.; Turcuş, V.; Olah, N.K.; Mathe, E. An overview of natural antimicrobials role in food. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, M.; Riaz, M.; Kanwal, N.; Mahmood, I.; Khan, A.; Bokhari, T.H.; Afzal, M. Evolution of Cytotoxicity, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Studies of Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) Roots Extracts. J. Chem. Soc. Pakistan 2017, 39, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.L.S.; Gondim, S.; Gómez-García, R.; Ribeiro, T.; Pintado, M. Olive leaf phenolic extract from two Portuguese cultivars–bioactivities for potential food and cosmetic application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Biswas, R.; Sharma, A.; Banerjee, S.; Biswas, S.; Katiyar, C.K. Validation of medicinal herbs for anti-tyrosinase potential. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-M.; Wang, H.-C.; El-Shazly, M.; Leu, Y.-L.; Cheng, M.-C.; Lee, C.-L.; Chang, F.-R.; Wu, Y.-C. Antioxidant and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Constituents from a Desugared Sugar Cane Extract, a Byproduct of Sugar Production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9219–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Yang, X.; Flavel, M.; Shields, Z.P.; Neoh, J.; Bowen, M.-L.; Kitchen, B. Age-Deterring and Skin Care Function of a Polyphenol Rich Sugarcane Concentrate. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S. Tyrosinase Inhibitors of Pulsatilla cernua Root-Derived Materials. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, M.; Chazarra, S.; Escribano, J.; Cabanes, J.; García-Carmona, F. Competitive Inhibition of Mushroom Tyrosinase by 4-Substituted Benzaldehydes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4060–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.-Y.; Ishiguro, K.; Kubo, I. Tyrosinase inhibitory p-Coumaric acid from Ginseng leaves. Phyther. Res. 1999, 13, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, K.; Kishimoto, N.; Kakino, Y.; Mochida, K.; Fujita, T. In Vitro Antioxidative Effects and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activities of Seven Hydroxycinnamoyl Derivatives in Green Coffee Beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4893–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; Oshima, T.; Koshio, K.; Itsuzaki, Y.; Anzai, J. Tyrosinase Inhibitor from Black Rice Bran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6953–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, J.S.; Dawso, S.R.; Hubbard, E.R.; Meyers, T.E.; Strothkamp, K.G. Inhibitor Binding to the Binuclear Active Site of Tyrosinase: Temperature, pH, and Solvent Deuterium Isotope Effects. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 5739–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S. An Updated Review of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 2440–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashraf, Z.; Rafiq, M.; Seo, S.-Y.; Babar, M.M.; Zaidi, N.-S.S. Synthesis, kinetic mechanism and docking studies of vanillin derivatives as inhibitors of mushroom tyrosinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 5870–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, Y.N.; Hwang, S.H.; Wang, Z.; Lim, S.S. Screening of Peruvian Medicinal Plants for Tyrosinase Inhibitory Properties: Identification of Tyrosinase Inhibitors in Hypericum laricifolium Juss. Molecules 2017, 22, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, C.P.; Chang, C.H.; Liang, C.C.; Hung, K.Y.; Hsieh, C.W. In Vitro Antioxidant Activities, Free Radical Scavenging Capacity, and Tyrosinase Inhibitory of Flavonoid Compounds and Ferulic Acid from Spiranthes sinensis (Pers.) Ames. Molecules 2014, 19, 4681–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Menichini, F. Natural and Synthetic Tyrosinase Inhibitors as Antibrowning Agents: An Update. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012, 11, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagesan, K.; Thennarasu, P.; Kumar, V.; Sankarnarayanan, S.; Balsamy, T. Identification of α-glucosidase inhibitors from Psidium guajava leaves and Syzygium cumini Linn. seeds. Int. J. Pharma Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 316–322. [Google Scholar]

- Boue, S.M.; Daigle, K.W.; Chen, M.-H.; Cao, H.; Heiman, M.L. Antidiabetic potential of purple and red rice (Oryza sativa L.) bran extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5345–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, K.; Zhang, J.; Bowyer, M.C.; Brunton, N.; Gibney, E.R.; Lyng, J. Fruit, vegetables, and mushrooms for the preparation of extracts with α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition properties: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmal, M.; Wadhwa, R. Alpha Glucosidase Inhibitors; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Taslimi, P.; Gulçin, İ. Antidiabetic potential: In vitro inhibition effects of some natural phenolic compounds on α-glycosidase and α-amylase enzymes. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2017, 31, e21956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Yu, S.; Zeng, F.; Wu, X. Phenolics content and inhibitory effect of sugarcane molasses on α-glucosidase and α-amylase in vitro. Sugar Tech 2016, 18, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Zhang, R.; Dong, L.; Chi, J.; Huang, F.; Dong, L.; Zhang, M.; Jia, X. α-Glucosidase inhibitors from brown rice bound phenolics extracts (BRBPE): Identification and mechanism. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tian, J.; Yang, W.; Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Fang, H.; Zhang, H.; Ye, X. Inhibition mechanism of ferulic acid against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Food Chem. 2020, 317, 126346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Zheng, B.; Yuan, Y.; Luo, D.; Fan, J. Comparative evaluation on phenolic profiles, antioxidant properties and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects of different milling fractions of foxtail millet. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 99, 103217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, F.; Xing, J.; Tsao, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S. Screening and structural characterization of α-glucosidase inhibitors from hawthorn leaf flavonoids extract by ultrafiltration LC-DAD-MSn and SORI-CID FTICR MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 20, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Lin, S.; Gong, D. Inhibitory Mechanism of Apigenin on α-Glucosidase and Synergy Analysis of Flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 6939–6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, A.D.; Aggarwal, A.S.; Harle, U.N.; Deshpande, A.D. DPP IV inhibitors: Successes, failures and future prospects. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2011, 5, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-masri, I.M.; Mohammad, M.K.; Tahaa, M.O. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) is one of the mechanisms explaining the hypoglycemic effect of berberine. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duez, H.; Cariou, B.; Staels, B. DPP-4 inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Imai, M.; Yamane, T.; Kozuka, M.; Takenaka, S.; Sakamoto, T.; Ishida, T.; Nakagaki, T.; Nakano, Y.; Inui, H. Caffeoylquinic acids from aronia juice inhibit both dipeptidyl peptidase IV and α-glucosidase activities. LWT 2020, 129, 109544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Cai, S.; Muhoza, B.; Qi, B.; Li, Y. Advance in dietary polyphenols as dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors to alleviate type 2 diabetes mellitus: Aspects from structure-activity relationship and characterization methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–16, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Li, T.; He, X.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; McClements, D.J. Analysis of inhibitory interaction between epigallocatechin gallate and alpha-glucosidase: A spectroscopy and molecular simulation study. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 230, 118023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Ouyang, J. Inhibitory effects of acorn (Quercus variabilis Blume) kernel-derived polyphenols on the activities of α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.R.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Alves, G.; Falcão, A.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A.; Silva, L.R. Valorisation of Prunus avium L. By-Products: Phenolic Composition and Effect on Caco-2 Cells Viability. Foods 2021, 10, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.G.; Ng, S.C. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burgos-Edwards, A.; Martín-Pérez, L.; Jiménez-Aspee, F.; Theoduloz, C.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Larrosa, M. Anti-inflammatory effect of polyphenols from Chilean currants (Ribes magellanicum and R. punctatum) after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on Caco-2 cells: Anti-inflammatory activity of in vitro digested Chilean currants. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 59, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.M.; Macedo, G.A.; Macedo, J.A. Biotransformed grape pomace as a potential source of anti-inflammatory polyphenolics: Effects in Caco-2 cells. Food Biosci. 2020, 35, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon De La Lastra, C.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.-C.; McIntosh, M.K. Potential mechanisms by which polyphenol-rich grapes prevent obesity-mediated inflammation and metabolic diseases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011, 31, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stote, K.S.; Clevidence, B.A.; Novotny, J.A.; Henderson, T.; Radecki, S.V.; Baer, D.J. Effect of cocoa and green tea on biomarkers of glucose regulation, oxidative stress, inflammation and hemostasis in obese adults at risk for insulin resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ambriz-Pérez, D.L.; Leyva-López, N.; Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Heredia, J.B. Phenolic compounds: Natural alternative in inflammation treatment. A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1131412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Jeong, S.-N.; Kim, Y.-C.; Kim, E.-C. Anti-inflammatory effects of apigenin on nicotine- and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human periodontal ligament cells via heme oxygenase-1. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.N.; Brenner, M.C.; Punessen, N.; Snodgrass, M.; Byars, C.; Arora, Y.; Linseman, D.A. Comparison of the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of the anthocyanin metabolites, protocatechuic acid and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 6297080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, N.; Liu, Q. Ferulic Acid Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Barrier Dysfunction via MicroRNA-200c-3p-Mediated Activation of PI3K/AKT Pathway in Caco-2 Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.S.; Satsu, H.; Bae, M.-J.; Zhao, Z.; Ogiwara, H.; Totsuka, M.; Shimizu, M. Anti-inflammatory effect of chlorogenic acid on the IL-8 production in Caco-2 cells and the dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis symptoms in C57BL/6 mice. Food Chem. 2015, 168, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, N.; Kitts, D.D. Chlorogenic Acid (CGA) Isomers Alleviate Interleukin 8 (IL-8) Production in Caco-2 Cells by Decreasing Phosphorylation of p38 and Increasing Cell Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romier-Crouzet, B.; van de Walle, J.; During, A.; Joly, A.; Rousseau, C.; Henry, O.; Larondelle, Y.; Schneider, Y.-J. Inhibition of inflammatory mediators by polyphenolic plant extracts in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucio-Noble, D.; Kautto, L.; Krisp, C.; Ball, M.S.; Molloy, M.P. Polyphenol extracts from dried sugarcane inhibit inflammatory mediators in an in vitro colon cancer model. J. Proteomics 2018, 177, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proposed Name | Formula-H | m/z Theoretical Mass [M−H]− | m/z Measured Mass [M−H]− | Error (ppm) | MS/MS Fragments (m/z) | Concentration (µg/g Dry Extract) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | |||||||

| 1 | 1-O-Vanilloyl-β-D-glucose | C14H17O9 | 329.0869 | 329.0878 | 2.6 | 167 | 306.55 ± 58.97 |

| 2 | Protocatechuic acid | C7H5O4 | 153.0184 | 153.0193 | 3.3 | 109, 153 | 24.79 ± 3.70 |

| 3 | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid isomer 1 | C7H5O4 | 153.0184 | 153.0193 | 3.2 | 109, 153 | 13.49 ± 1.34 |

| 4 | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid isomer 2 | C7H5O4 | 153.0181 | 153.0193 | 3.3 | 65, 109 | 301.78 ± 49.36 |

| 5 | Gentisic acid 2-O-β-glucoside | C13H14O9 | 315.0713 | 315.0722 | 2.7 | 108, 152 | 34.89 ± 9.66 |

| 6 | Gentisic acid 5-O-β-glucoside | C13H14O9 | 315.0712 | 315.0722 | 2.9 | 109, 153 | 32.96 ± 6.97 |

| 7 | Protocatechuic acid 4-β-glucoside | C13H14O9 | 315.0716 | 315.0722 | 1.6 | 109, 153 | 9.91 ± 2.32 |

| 8 | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H5O3 | 137.0235 | 137.0244 | 4.6 | 137 | 21.99 ± 3.44 |

| 9 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H5O3 | 137.0233 | 137.0244 | 4.5 | 93, 137 | 53.69 ± 5.00 |

| 10 | 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H5O2 | 121.0285 | 121.0295 | 3.0 | 121 | 316.04 ± 40.13 |

| 11 | Syringic acid | C9H9O5 | 197.0445 | 197.0455 | −1.9 | 123 | 97.21 ± 13.50 |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | |||||||

| 12 | Neochlorogenic acid | C16H17O9 | 353.0866 | 353.0878 | 3.4 | 135, 179, 191 | 239.43 ± 62.19 |

| 13 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H17O9 | 353.0864 | 353.0878 | 4.0 | 191 | 407.28 ± 78.46 |

| 14 | 4-Caffeoylquinic acid isomer 1 | C16H17O9 | 353.0866 | 353.0878 | 3.5 | 135, 173, 179, 191 | 200.28 ± 37.50 |

| 15 | 4-Caffeoylquinic acid isomer 2 | C16H17O9 | 353.0864 | 353.0865 | 0.2 | 191 | 211.58 ± 19.16 |

| 16 | cis-5-O-p-Coumaroylquinic acid isomer 1 | C16H17O8 | 337.0919 | 337.0929 | 3.1 | 93, 163, 173, 191 | 27.46 ± 3.46 |

| 17 | cis-5-O-p-Coumaroylquinic acid isomer 2 | C16H17O8 | 337.0919 | 337.0929 | 3.1 | 191 | 12.41 ± 1.70 |

| 18 | 5-O-Feruloylquinic acid | C17H19O9 | 367.1021 | 367.1035 | 3.8 | 134, 193 | 439.01 ± 97.24 |

| 19 | trans-3-Feruloylquinic acid | C17H19O9 | 367.1023 | 367.1030 | 3.5 | 173 | 247.79 ± 34.89 |

| 20 | Caffeic acid | C9H7O4 | 179.0337 | 179.0350 | −0.5 | 135, 179 | 106.33 ± 16.53 |

| 21 | Ferulic acid | C10H9O4 | 193.0391 | 193.0506 | 4.3 | 134, 161, 193 | 60.28 ± 5.64 |

| 22 | p-Coumaric acid | C9H7O3 | 163.0401 | 163.0401 | −1.0 | 119 | 221.30 ± 31.28 |

| 23 | Caffeoylquinic acid | C16H17O9 | 515.1220 | 515.1202 | 2.3 | 515 | 134.07 ± 15.60 |

| 24 | 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | C25H23O12 | 515.1196 | 515.1202 | 2.3 | 173, 179, 191, 335, 353 | 42.99 ± 1.77 |

| 25 | Caffeoylshikimic acid isomer 1 | C16H15O8 | 335.071 | 335.0772 | −0.6 | 135, 161, 179 | 18.28 ± 1.43 |

| 26 | Caffeoylshikimic acid isomer 2 | C16H15O8 | 335.071 | 335.0772 | −0.5 | 135, 161, 179 | 22.81 ± 0.86 |

| Flavonoids | |||||||

| 27 | Apigenin-8-C-glucoside isomer 1 | C21H19O10 | 431.1917 | 431.1923 | 1.4 | 89, 179 | 50.97 ± 7.67 |

| 28 | Apigenin-8-C-glucoside isomer 2 | C21H19O10 | 431.1912 | 431.1923 | 2.5 | 311, 341, 431 | 288.09 ± 40.42 |

| 29 | Apigenin-8-C-glucoside isomer 3 | C21H19O10 | 431.0982 | 431.1923 | 2.4 | 311, 341 | 37.18 ± 1.98 |

| 30 | Apigenin-8-C-glucoside isomer 4 | C21H19O10 | 431.0975 | 431.0984 | 2.1 | 311, 341 | 112.33 ± 4.81 |

| 31 | Apigenin-8-C-glucoside isomer 5 | C21H19O10 | 431.0984 | 431.0984 | 0.0 | 327, 341, 357 | 18.84 ± 1.75 |

| 32 | Apigenin-8-C-glucoside isomer 6 | C21H19O10 | 431.1352 | 431.0984 | 0.0 | 327, 357 | 88.45 ± 2.87 |

| 33 | Isovitexin 2″-O-arabinoside | C26H27O14 | 563.1401 | 563.1406 | 1.9 | 353, 443 | 28.27 ± 1.68 |

| 34 | Isoschaftoside | C26H27O14 | 563.1395 | 563.1406 | 1.9 | 353, 473 | 257.76 ± 30.24 |

| 35 | Neoschaftoside | C26H27O14 | 563.1403 | 563.1406 | 0.5 | 399, 473 | 43.61 ± 3.82 |

| 36 | Apigenin-6-C-arabinoside-8-C-glucoside | C26H27O14 | 563.1397 | 563.1379 | −3.1 | 293, 413 | 63.86 ± 4.24 |

| 37 | Luteolin-8-C-glucoside isomer 1 | C21H19O11 | 447.0920 | 447.0933 | 2.9 | 327, 357 | 156.30 ± 8.42 |

| 38 | Luteolin-8-C-glucoside isomer 2 | C21H19O11 | 447.0920 | 447.0933 | 2.9 | 327, 357 | 87.15 ± 14.71 |

| 39 | Vitexin 2″-O-beta-L-rhamnoside | C27H29O14 | 577.1559 | 577.1563 | 0.7 | 293, 413 | 62.21 ± 0.86 |

| 40 | Apigenin 7-O-neohesperidoside | C27H29O14 | 577.1556 | 577.1563 | 1.2 | 293, 413, 473 | 59.86 ± 0.86 |

| 41 | Luteolin | C15H9O6 | 285.0407 | 285.0405 | −1.0 | 285 | 66.56 ± 1.30 |

| 42 | 6-Methoxyluteolin 7-rhamnoside isomer 1 | C22H21O11 | 461.1083 | 461.1089 | 1.4 | 461 | 42.85 ± 4.38 |

| 43 | 6-Methoxyluteolin 7-rhamnoside isomer 2 | C22H21O11 | 461.1088 | 461.1136 | 2.3 | 341, 371 | 36.61 ± 0.98 |

| 44 | Tricin-O-neohesperoside isomer 1 | C29H33O16 | 637.1772 | 637.1774 | −3.9 | 329 | 60.07 ± 0.11 |

| 45 | Tricin-O-neohesperoside isomer 2 | C29H33O16 | 637.1775 | 637.1638 | −0.1 | 329 | 53.80 ± 0.64 |

| 46 | Tricin-7-O-glucoside | C25H31O10 | 491.1919 | 491.1823 | 0.7 | 329 | 132.62 ± 7.58 |

| 47 | Tricin-7-O-rhamnosyl-glucuronide | C29H31O17 | 651.1570 | 651.1567 | −0.4 | 329 | 76.29 ± 1.34 |

| 48 | Tricin-4-(O-erythro) ether glucoside isomer 1 | C33H35O16 | 687.1941 | 687.1786 | 3.1 | 165, 195, 329, 491, 525 | 84.31 ± 3.25 |

| 49 | Tricin-4-(O-erythro) ether glucoside isomer 2 | C33H35O16 | 687.1937 | 687.1786 | 3.0 | 165, 195, 329, 491, 526 | 69.40 ± 4.25 |

| 50 | Tricin | C17H13O7 | 329.0664 | 329.0667 | 1.0 | 299 | 248.14 ± 3.40 |

| Standard | Concentration Range (µg/mL) | Equation Curve | Determination Coeficiente (R2) | LOD (µg/mL) | LOQ (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitexin | 0.06–1.96 | y = 10889817 x + 98542 | 0.96 | 0.23 | 0.71 |

| Diosmetin | 0.06–1.90 | y = 3875491 x + 774787 | 0.96 | 0.66 | 2.00 |

| Isoschaftoside | 0.02–0.70 | y = 9619455 x + 380002 | 0.98 | 0.17 | 0.53 |

| Orientin | 0.03–0.95 | y = 3245142 x + 223820 | 0.98 | 0.28 | 0.84 |

| Vitexin-2-O-rhamnoside | 0.06–1.96 | y = 3617818 x + 550052 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 0.84 |

| Tricin | 0.01–0.47 | y = 8999089 x + 145571 | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.42 |

| Luteolin | 0.06–1.96 | y = 6729048 x + 1778703 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 2.25 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 0.09–1.40 | y = 1586510 x + 60821 | 0.99 | 0.29 | 0.72 |

| Vanillic acid | 0.02–0.64 | y = 1045485 x − 46131 | 0.99 | 0.24 | 0.72 |

| p-Coumaric acid | 0.14–1.14 | y = 3125587 x + 40037 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 1.33 |

| Caffeic acid | 0.15–1.24 | y = 2508428 x + 118063 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 2.42 |

| Ferulic acid | 0.13–1.07 | y = 1143919 x + 25137 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 1.45 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.12–0.95 | y = 779052 x + 52629 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 2.59 |

| 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 0.15–1.18 | y = 1852876 x + 85535 | 0.99 | 0.40 | 1.21 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | 0.15–1.19 | y = 8654434 x − 50043 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 1.13 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 0.14–1.12 | y = 5072196 x − 20201 | 0.99 | 0.11 | 0.34 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde | 0.14–1.20 | y = 2190795 x + 65616 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 1.07 |

| Syringic acid | 0.16–1.26 | y = 405197 x + 14954 | 0.93 | 1.15 | 3.49 |

| Antioxidant Activity | ABTS | DPPH |

|---|---|---|

| (mg TE/g Dry Extract) | ||

| Sugarcane straw extract | 53.1 ± 0.0 | 33.0 ± 0.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, A.L.S.; Carvalho, M.J.; Oliveira, D.L.; Costa, E.; Pintado, M.; Madureira, A.R. Sugarcane Straw Polyphenols as Potential Food and Nutraceutical Ingredient. Foods 2022, 11, 4025. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11244025

Oliveira ALS, Carvalho MJ, Oliveira DL, Costa E, Pintado M, Madureira AR. Sugarcane Straw Polyphenols as Potential Food and Nutraceutical Ingredient. Foods. 2022; 11(24):4025. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11244025

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Ana L. S., Maria João Carvalho, Diana Luazi Oliveira, Eduardo Costa, Manuela Pintado, and Ana Raquel Madureira. 2022. "Sugarcane Straw Polyphenols as Potential Food and Nutraceutical Ingredient" Foods 11, no. 24: 4025. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11244025