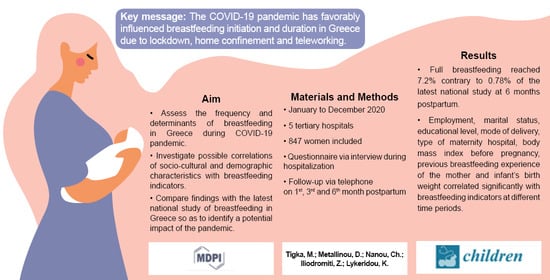

Frequency and Determinants of Breastfeeding in Greece: A Prospective Cohort Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- General and Maternity Hospital “HELENA VENIZELOU” (24285/29 October 2019)

- “ATTIKON” General University Hospital (570/1 October 2019)

- “ALEXANDRA” General Hospital (511/20 July 2020)

- “IASO” General Maternity and Gynecology Clinic (30 May 2019)

- “LETO” General, Maternity and Gynecology Clinic (174a/5 June 2019)

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Definitions of Breastfeeding

- Breastfeeding (BF), hereafter referred to as ‘any breastfeeding’, implies that the child receives breast milk (direct from the breast or expressed). The infant is allowed to receive any food or liquid including non-human milk.

- Exclusive Breastfeeding (EBF) implies that the infant receives only breast milk, including expressed breast milk or milk from a wet nurse, and allows the infant to receive drops and syrups (vitamins, minerals and medicines), but does not allow anything else.

- Predominant Breastfeeding (PBF) implies that the infant receives breast milk (including milk expressed or from wet nurse) as the predominant source of nourishment, and also allows liquids (water, and water-based drinks, fruit juice and oral rehydration solution), ritual fluids and drops or syrups (vitamins, minerals and medicines). Non-human milk and food-based fluids are forbidden when defining PBF.

- Full Breastfeeding (FBF) is defined as exclusive and predominant breastfeeding together.

- Mixed Breastfeeding (MBF) implies that the infant receives breast milk, allowing liquid and non-human milk intake.

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Sample Characteristics

3.2. Breastfeeding Indicators

- Any Breastfeeding (ABF): The percentage of infants who were breastfeeding the fourth day of life (usual day of discharge in Greece) was 94.1% and reached 84% at the end of the first month. In the following months, a small drop was observed in the breastfeeding rates, as 69.2% of the infants were still breastfeeding in the third completed month of life. At the end of the six month follow-up, 53.1% of the infants were still breastfeeding.

- Full Breastfeeding: The percentage of infants who were fully breastfed the day of discharge was 53.5% and reached 47.2% at the end of the first month. A gradual decline was observed in the following period, as 40.7% of the infants continued FBF at the third completed month of life. Then, there was a rapid reduction in the rate and the percentage fell to 7.2% at the end of the six month of life.

- Breastfeeding without human-milk substitute: The fourth day of life, 53.5% of the infants were breastfeeding without human-milk substitute. This percentage fell to 47.2% and 40.7% at the end of the first and third month, respectively. At the end of the six month of life, 30.7% of the infants were breastfeeding without receiving or having ever received any human-milk substitute.

- Mixed Breastfeeding: On the fourth day of life, many mothers (40.6%) were breastfeeding and also giving a human-milk substitute to their infants. A decrease in this percentage was observed at the end of the first (36.8%) and third (28.5%) month of life, since some of the women stopped giving a human-milk substitute to their infant and continued with FBF. At the end of the sixth months, however, the percentage of MBF rose again (45.9%), implying that some women started giving a human-milk substitute anew.

- Introduction of solid/semi-solid foods: Information regarding the introduction of solid/semi-solids foods was obtained at the six-month follow-up from 450 women out of the 847 who took part in the study. The number of women who responded was smaller due to the fact that only mothers who continued breastfeeding were contacted at this final follow-up stage. The introduction of solid/semi-solid foods was detected to have started already from the beginning of the fourth month of life (1.7%) and there was a vertical increase in the percentages in the following months. In the fifth month, most of the infants (83.3%) had received solid/semi-solid foods or fruit juice, while the percentage reached 100% in the sixth completed month of life.

- Breastfeeding cessation: As far as breastfeeding cessation is concerned, our results showed that a minority of women (5.9%) had stopped breastfeeding until the fourth postpartum day. This percentage rose to 16%, 30.8% and 46.9% at the end of the first-, third- and sixth- month follow-up, respectively.

3.3. Causes of Breastfeeding Cessation

3.4. Factors Related to Breastfeeding Indicators

- OR = 5.9 (95% C.I.: 4.1, 8.5), OR = 12.9 (95% C.I.: 8.2, 20.2) and OR = 11.7 (95% C.I.: 2.8, 49.1) to fully breastfeed their infant in the first, third and sixth month postpartum, respectively (p ≤ 0.001).

- OR = 66.6 (95% C.I.: 38.2, 116.1) to follow any breastfeeding at six months postpartum (p < 0.001).

- OR = 31.6 (95% C.I.: 15.8, 63.2) to breastfeed their infant without giving any human-milk substitute at six months postpartum (p < 0.001).

3.5. Comparison of the Present Study with the Latest National Study in Greece

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McAdams, R.M. Beauty of Breastfeeding. J. Hum. Lact. 2021, 37, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Giannì, M.L. Human milk: Composition and health benefits. Pediatr. Med. Chir. 2017, 39, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spatz, D.L. Breastfeeding is the cornerstone of childhood nutrition. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 41, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosi, A.T.B.; Eriksen, K.G.; Sobko, T.; Wijnhoven, T.M.; Breda, J. Breastfeeding practices and policies in WHO European Region Member States. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Ciampo, L.A.; Del Ciampo, I.R.L. Breastfeeding and the Benefits of Lactation for Women’s Health. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2018, 40, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lau, C. Breastfeeding Challenges and the Preterm Mother-Infant Dyad: A Conceptual Model. Breastfeed. Med. 2018, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44117/9789241597494_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/49801/file/From-the-first-hour-of-life-ENG.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Neves, P.A.R.; Vaz, J.S.; Maia, F.S.; Baker, P.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Piwoz, E.; Rollins, N.; Victora, C.G. Rates and time trends in the consumption of breastmilk, formula, and animal milk by children younger than 2 years from 2000 to 2019: Analysis of 113 countries. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/breastfeeding/ (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- WHO. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/maternal-and-newborn-health/news/news/2015/08/who-european-region-has-lowest-global-breastfeeding-rates (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Theurich, M.A.; Davanzo, R.; Busck-Rasmussen, M.; Díaz-Gómez, N.M.; Brennan, C.; Kylberg, E.; Bærug, A.; McHugh, L.; Weikert, C.; Abraham, K.; et al. Breastfeeding Rates and Programs in Europe: A Survey of 11 National Breastfeeding Committees and Representatives. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, V.; Lee, A.H.; Scott, J.A.; Karkee, R.; Binns, C.W. Implications of methodological differences in measuring the rates of exclusive breastfeeding in Nepal: Findings from literature review and cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iliodromiti, Z.; Zografaki, I.; Papamichail, D.; Stavrou, T.; Gaki, E.; Ekizoglou, C.; Nteka, E.; Mavrika, P.; Zidropoulos, S.; Panagiotopoulos, T.; et al. Increase of breast-feeding in the past decade in Greece, but still low uptake: Cross-sectional studies in 2007 and 2017. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavoulari, E.F.; Benetou, V.; Vlastarakos, P.V.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Chrousos, G.; Kreatsas, G.; Gryparis, A.; Linos, A. Factors affecting breastfeeding duration in Greece: What is important? World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2016, 5, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, R.; Partridge, E.; Kairm, L.R.; Kuhn-Riordon, K.M.; Silva, A.I.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Chantry, C.J.; Underwood, M.A.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Blumberg, D. Protecting Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/nutrition/nutrition-infocus/breastfeeding-advice-during-covid-19-outbreak.html (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Calil, V.M.L.T.; Krebs, V.L.J.; Carvalho, W.B. Guidance on breastfeeding during the Covid-19 pandemic. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2020, 66, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaceci, S.; Giusti, A.; De Angelis, A.; Della Barba, M.I.; De Vincenti, A.Y.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R. Medications, “Natural” Products, and Pharmacovigilance during Breastfeeding: A Mixed-Methods Study on Women’s Opinions. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirm, E.; Schwagermann, M.P.; Tobi, H.; de Jong-van den Berg, L.T. Drug use during breastfeeding. A survey from the Netherlands. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsanidou, E.; Gougoula, V.; Tselebonis, A.; Kontogiorgis, C.; Constantinidis, T.C.; Nena, E. Socio-demographic Factors Affecting Initiation and Duration of Breastfeeding in a Culturally Diverse Area of North Eastern Greece. Folia Med. Plovdiv 2019, 61, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vassilaki, M.; Chatzi, L.; Bagkeris, E.; Papadopoulou, E.; Karachaliou, M.; Koutis, A.; Philalithis, A.; Kogevinas, M. Smoking and caesarean deliveries: Major negative predictors for breastfeeding in the mother-child cohort in Crete, Greece (Rhea study). Matern. Child. Nutr. 2014, 10, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakoula, C.; Nicolaidou, P.; Veltsista, A.; Prezerakou, A.; Moustaki, M.; Kavadias, G.; Lazaris, D.; Fretzayas, A.; Krikos, X.; Karpathios, T.; et al. Does exclusive breastfeeding increase after hospital discharge? A Greek study. J. Hum. Lact. 2007, 23, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester-Knauss, C.; Merten, S.; Weiss, C.; Ackermann-Liebrich, U.; Zemp Stutz, E. The baby-friendly hospital initiative in Switzerland: Trends over a 9-year period. J. Hum. Lact. 2013, 29, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Latorre, G.; Martinelli, D.; Guida, P.; Masi, E.; De Benedictis, R.; Maggio, L. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on exclusive breastfeeding in non-infected mothers. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, M.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Van Calsteren, K.; Eerdekens, A.; Allegaert, K.; Foulon, V. SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Results from an Observational Study in Primary Care in Belgium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.; Shenker, N. Experiences of breastfeeding during COVID-19: Lessons for future practical and emotional support. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2021, 17, e13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, E.C.; Li, R.; Scanlon, K.S.; Perrine, C.G.; Grummer-Strawn, L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e726–e732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, C.R.; Dodds, L.; Legge, A.; Bryanton, J.; Semenic, S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can. J. Public Health. 2014, 105, e179–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliadou, M.; Lykeridou, K.; Prezerakos, P.; Swift, E.M.; Tziaferi, S.G. Measuring the Effectiveness of a Midwife-led Education Programme in Terms of Breastfeeding Knowledge and Self-efficacy, Attitudes Towards Breastfeeding, and Perceived Barriers of Breastfeeding Among Pregnant Women. Mater. Sociomed. 2018, 30, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchini-Raies, C.; Márquez-Doren, F.; Garay Unjidos, N.; Contreras Véliz, J.; Jara Suazo, D.; Calabacero Florechaes, C.; Campos Romero, S.; Lopez-Dicastillo, O. Care during Breastfeeding: Perceptions of Mothers and Health Professionals. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2019, 37, e09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Antoniou, E.; Orovou, E.; Iliadou, M.; Sarella, A.; Palaska, E.; Sarantaki, A.; Iatrakis, G.; Dagla, M. Factors Associated with the Type of Cesarean Section in Greece and Their Correlation with International Guidelines. Acta Inform. Med. 2021, 29, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedefaw, G.; Goedert, M.H.; Abebe, E.; Demis, A. Effect of cesarean section on initiation of breast feeding: Findings from 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, E.; Santhakumaran, S.; Gale, C.; Philipps, L.H.; Modi, N.; Hyde, M.J. Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Economou, M.; Kolokotroni, O.; Paphiti-Demetriou, I.; Kouta, C.; Lambrinou, E.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Hadjiona, V.; Tryfonos, F.; Philippou, E.; Middleton, N. Prevalence of breast-feeding and exclusive breast-feeding at 48 h after birth and up to the sixth month in Cyprus: The BrEaST start in life project. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baumgartner, T.; Bhamidipalli, S.S.; Guise, D.; Daggy, J.; Parker, C.B.; Westermann, M.; Parry, S.; Grobman, W.A.; Mercer, B.M.; Simhan, H.N.; et al. nuMoM2b study. Psychosocial and Sociodemographic Contributors to Breastfeeding Intention in First-Time Mothers. Matern. Child. Health J. 2020, 24, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Krebs, N.F.; Young, B.E.; Cabana, M.D.; Erdmann, P.; Hays, N.P.; Bezold, C.P.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Turini, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 190–196.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santana, G.S.; Giugliani, E.R.J.; Vieira, T.O.; Vieira, G.O. Factors associated with breastfeeding maintenance for 12 months or more: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Rio J. 2018, 94, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habtewold, T.D.; Endalamaw, A.; Mohammed, S.H.; Mulugeta, H.; Dessie, G.; Kassa, G.M.; Asmare, Y.; Tadese, M.; Alemu, Y.M.; Sharew, N.T.; et al. Sociodemographic Factors Predicting Exclusive Breastfeeding in Ethiopia: Evidence from a Meta-analysis of Studies Conducted in the Past 10 Years. Matern. Child. Health J. 2021, 25, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangrio, E.; Persson, K.; Bramhagen, A.C. Sociodemographic, physical, mental and social factors in the cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months: A systematic review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, T.; Woldemichael, K.; Jarso, H.; Bekele, B.B. Exclusive breastfeeding cessation and associated factors among employed mothers in Dukem town, Central Ethiopia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shafaei, F.S.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Havizari, S. The effect of prenatal counseling on breastfeeding self-efficacy and frequency of breastfeeding problems in mothers with previous unsuccessful breastfeeding: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Ouyang, Y.Q.; Redding, S.R. Previous breastfeeding experience and its influence on breastfeeding outcomes in subsequent births: A systematic review. Women Birth 2019, 32, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Greek | 774 (91.4) |

| Other | 73 (8.6) | |

| Education | None/Elementary | 8 (0.9) |

| Junior High/High school | 155 (18.3) | |

| College | 142 (16.8) | |

| University | 400 (47.2) | |

| Postgraduate studies | 142 (16.8) | |

| Marital status | Married | 808 (95.4) |

| Single | 39 (4.6) | |

| Living with a partner | Yes | 845 (99.8) |

| No | 2 (0.2) | |

| Residence | Attica | 661 (78.0) |

| Provinces | 186 (22.0) | |

| Employment before pregnancy | Yes | 685 (80.9) |

| No | 162 (19.1) | |

| Employment at sixth month after delivery | Yes | 306 (36.1) |

| No | 541(63.9) | |

| Work suspension due to COVID-19 pandemic | 85 (10.1) | |

| Teleworking due to COVID-19 pandemic | 133 (15.7) | |

| Maternity leave | 152 (17.9) | |

| Not employed | 171 (20.2) | |

| Type of hospital | Private | 464 (54.8) |

| Public | 383 (45.2) | |

| Gravida | Primigravida | 443 (52.3) |

| Secondgravida | 326 (38.5) | |

| Multigravida | 78 (9.2) | |

| Mode of delivery | Vaginal birth | 281 (33.2) |

| Caesarean section | 566 (66.8) | |

| Type of pregnancy | Singleton | 834 (98.5) |

| Twin | 13 (1.5) | |

| Newborn’s sex | Female Male | 414 (48.2) 445 (51.8) |

| Gestational age of the newborn | Preterm < 34 weeks Late preterm 34–36+6 weeks Term 37–41+6 weeks | 17 (2.0) 66 (7.7) 776 (90.3) |

| Birth weight of the newborn < 2500 gr | Yes No | 64 (7.5) 795 (92.5) |

| Variable | Median (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (all women) | 34.0 (17.0, 44.0) | 33.7 ± 4.7 | 847 |

| Age (primigravida) | 33.0 (17.0, 44.0) | 32.5 ± 4.7 | 443 |

| Duration of pregnancy (weeks) | 38.4 (30.0, 42.0) | 38.3 ± 1.5 | 847 |

| BMI before pregnancy | 22.9 (15.9, 50.7) | 24.2 ± 5.0 | 847 |

| BMI before delivery | 27.7 (19.0, 54.7) | 28.6 ± 4.8 | 847 |

| Birth weight of the newborn | 3160.0 (1290.0, 4900.0) | 3134.4 ± 451.2 | 859 |

| Breastfeeding duration (days) | 180 (0, 181) | 123.88 ± 70.08 | 847 |

| No Smoking before pregnancy—Breastfeeding duration | 180 (0, 181) | 130.17 ± 67.13 | 581 |

| Smoking before pregnancy (Yes)—Breastfeeding duration | 135 (0, 181) | 110.12 ± 74.43 | 266 |

| Smoking before pregnancy (Total)—Breastfeeding duration | 180 (0, 181) | 123.88 ± 70.08 | 847 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Breast-related causes | ||

| Perceived low milk quantity | 180 | 45.3 |

| Nipple soreness and cracking- Mastodynia | 9 | 2.3 |

| Mastitis | 10 | 2.5 |

| Flat nipples | 6 | 1.5 |

| Nipple discharge-dermatitis of the nipple | 1 | 0.3 |

| Infant’s ineffective attachment to the breast | 17 | 4.3 |

| Mother-related causes | ||

| Choice | 34 | 8.6 |

| Medication intake | 57 | 14.4 |

| Smoking | 11 | 2.8 |

| Caffeine consumption | 1 | 0.3 |

| Return to work | 12 | 3.0 |

| Disease | 6 | 1.5 |

| Initiation of pregnancy | 2 | 0.5 |

| Difficulty in time management, Fatigue, Poor sense of self-efficacy | 21 | 5.6 |

| Bad breastfeeding experience | 5 | 1.3 |

| Infant-related causes | ||

| Hospitalization | 6 | 1.5 |

| Poor weight gain | 5 | 1.3 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 4 | 1.0 |

| Jaundice | 1 | 0.3 |

| Infant’s preference to non-human milk | 5 | 1.3 |

| Possible allergy to dairy products | 2 | 0.5 |

| Total | 397 | 100.0 |

| Infant’s Age | FBF (%) | BFWHMS (%) | ABF (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Τigka et al. | ΙCH | Τigka et al. | ΙCH | Τigka et al. | ΙCH | |

| 4 days a/1 week b | 53.5 | 51.13 | 53.5 | 51.13 | 94.1 | 90.84 |

| 1 month | 47.2 | 42.16 | 47.2 | 42.16 | 84.0 | 79.89 |

| 3 months | 40.7 | 32.16 | 40.7 | 32.16 | 69.2 | 63.47 |

| 6 months | 7.2 | 0.78 | 30.7 | 23.53 | 53.1 | 45.39 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tigka, M.; Metallinou, D.; Nanou, C.; Iliodromiti, Z.; Lykeridou, K. Frequency and Determinants of Breastfeeding in Greece: A Prospective Cohort Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2022, 9, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9010043

Tigka M, Metallinou D, Nanou C, Iliodromiti Z, Lykeridou K. Frequency and Determinants of Breastfeeding in Greece: A Prospective Cohort Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children. 2022; 9(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleTigka, Maria, Dimitra Metallinou, Christina Nanou, Zoi Iliodromiti, and Katerina Lykeridou. 2022. "Frequency and Determinants of Breastfeeding in Greece: A Prospective Cohort Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Children 9, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9010043