Role of Chemerin in Cardiovascular Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Search Strategy

2. Cardiovascular Disease (CVDs)

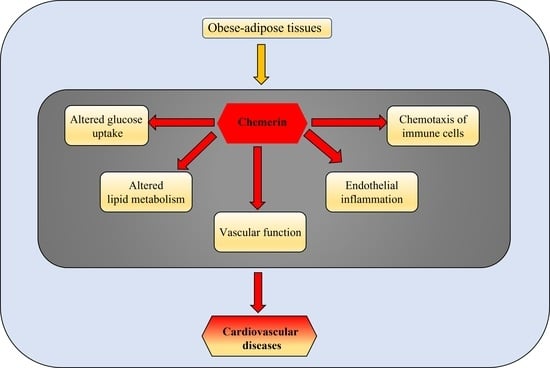

3. Chemerin

3.1. Chemerin and CVDs

3.1.1. Evidence from Human Studies Supporting Chemerin’s Role in CVDs

3.1.2. Chemerin Roles in CVDs: Evidence from Animal Studies

4. Perspectives for the Development of Chemerin-Targeting Therapeutic Agents

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, A.A.; Stoian, A.P. Metabolic Syndrome: From Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karastergiou, K.; Mohamed-Ali, V. The autocrine and paracrine roles of adipokines. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 318, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pardo, M.; Roca-Rivada, A.; Seoane, L.M.; Casanueva, F.F. Obesidomics: Contribution of adipose tissue secretome analysis to obesity research. Endocrine 2012, 41, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Fuster, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines: A link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizvi, A.A.; Nikolic, D.; Sallam, H.S.; Montalto, G.; Rizzo, M.; Abate, N. Adipokines and lipoproteins: Modulation by antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic agents. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2014, 12, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Mattu, H.S.; Chatha, K.; Randeva, H.S. Chemerin in human cardiovascular disease. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 110, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, N.; Sallam, H.S.; Rizzo, M.; Nikolic, D.; Obradovic, M.; Bjelogrlic, P.; Isenovic, E.R. Resistin: An inflammatory cytokine. Role in cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4961–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, M.; Stepien, A.; Wlazel, R.N.; Paradowski, M.; Rizzo, M.; Banach, M.; Rysz, J. Predictors of insulin resistance in patients with obesity: A pilot study. Angiology 2014, 65, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goralski, K.B.; McCarthy, T.C.; Hanniman, E.A.; Zabel, B.A.; Butcher, E.C.; Parlee, S.D.; Muruganandan, S.; Sinal, C.J. Chemerin, a novel adipokine that regulates adipogenesis and adipocyte metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 28175–28188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zabel, B.A.; Kwitniewski, M.; Banas, M.; Zabieglo, K.; Murzyn, K.; Cichy, J. Chemerin regulation and role in host defense. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, T.; Oppenheim, J.J. Chemerin reveals its chimeric nature. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2187–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ernst, M.C.; Sinal, C.J. Chemerin: At the crossroads of inflammation and obesity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2010, 21, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rourke, J.L.; Dranse, H.J.; Sinal, C.J. Towards an integrative approach to understanding the role of chemerin in human health and disease. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2013, 14, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, J.; Gu, W.; Dai, M.; Shi, J.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Ning, G. The association of serum chemerin level with risk of coronary artery disease in Chinese adults. Endocrine 2012, 41, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Ji, W.; Zhang, Y. Elevated serum chemerin levels are associated with the presence of coronary artery disease in patients with metabolic syndrome. Intern. Med. 2011, 50, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Kou, W.; Ji, S.; Shen, R.; Ji, H.; Zhuang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Peng, W.; Yu, X.; et al. Prognostic value of plasma adipokine chemerin in patients with coronary artery disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 968349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiroglou, S.G.; Kostopoulos, C.G.; Varakis, J.N.; Papadaki, H.H. Adipokines in periaortic and epicardial adipose tissue: Differential expression and relation to atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2010, 17, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Choi, H.Y.; Yang, S.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Seo, J.A.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, N.H.; Choi, K.M.; Choi, D.S.; Baik, S.H. Circulating chemerin level is independently correlated with arterial stiffness. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2012, 19, 59–66; discussion 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lehrke, M.; Becker, A.; Greif, M.; Stark, R.; Laubender, R.P.; von Ziegler, F.; Lebherz, C.; Tittus, J.; Reiser, M.; Becker, C.; et al. Chemerin is associated with markers of inflammation and components of the metabolic syndrome but does not predict coronary atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 161, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flora, G.D.; Nayak, M.K. A Brief Review of Cardiovascular Diseases, Associated Risk Factors and Current Treatment Regimes. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 4063–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquera, S.; Pedroza-Tobías, A.; Medina, C.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Lozano, R.; Moran, A.E. Global Overview of the Epidemiology of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2015, 46, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, A.A.; Popovic, D.S.; Papanas, N.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Al Mahmeed, W.; Sahebkar, A.; Janez, A.; Rizzo, M. Current and emerging drugs for the treatment of atherosclerosis: The evidence to date. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 20, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.D.; Leitinger, N.; Navab, M.; Faull, K.F.; Hörkkö, S.; Witztum, J.L.; Palinski, W.; Schwenke, D.; Salomon, R.G.; Sha, W.; et al. Structural identification by mass spectrometry of oxidized phospholipids in minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein that induce monocyte/endothelial interactions and evidence for their presence in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 13597–13607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Libby, P.; Theroux, P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation 2005, 111, 3481–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Y.M. CD36, a scavenger receptor implicated in atherosclerosis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2014, 46, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizzo, M.; Corrado, E.; Coppola, G.; Muratori, I.; Novo, G.; Novo, S. Markers of inflammation are strong predictors of subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis in women with hypertension. Coron. Artery Dis. 2009, 20, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardu, C.; Paolisso, G.; Marfella, R. Inflammatory Related Cardiovascular Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targets. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaddagh, A.; Martin, S.S.; Leucker, T.M.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Lowenstein, C.J.; Jones, S.R.; Toth, P.P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, N.; Du, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X. Visfatin Amplifies Cardiac Inflammation and Aggravates Cardiac Injury via the NF-κB p65 Signaling Pathway in LPS-Treated Mice. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 3306559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trpkovic, A.; Obradovic, M.; Petrovic, N.; Davidovic, R.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Isenovic, E.R. C-Reactive Protein. In Encyclopedia of Signaling Molecules; Choi, S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- LaPointe, M.C.; Isenović, E. Interleukin-1beta regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 involves the p42/44 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes. Hypertension 1999, 33, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marfella, R.; Grella, R.; Rizzo, M.R.; Barbieri, M.; Grella, R.; Ferraraccio, F.; Cacciapuoti, F.; Mazzarella, G.; Ferraro, N.; D’Andrea, F.; et al. Role of subcutaneous abdominal fat on cardiac function and proinflammatory cytokines in premenopausal obese women. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2009, 63, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sardu, C.; Pieretti, G.; D’Onofrio, N.; Ciccarelli, F.; Paolisso, P.; Passavanti, M.B.; Marfella, R.; Cioffi, M.; Mone, P.; Dalise, A.M.; et al. Inflammatory Cytokines and SIRT1 Levels in Subcutaneous Abdominal Fat: Relationship With Cardiac Performance in Overweight Pre-diabetics Patients. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sardu, C.; Carreras, G.; Katsanos, S.; Kamperidis, V.; Pace, M.C.; Passavanti, M.B.; Fava, I.; Paolisso, P.; Pieretti, G.; Nicoletti, G.F.; et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with a poor outcome in patients affected by outflow tract premature ventricular contractions treated by catheter ablation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2014, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, J.H.; Korcarz, C.E.; Hurst, R.T.; Lonn, E.; Kendall, C.B.; Mohler, E.R.; Najjar, S.S.; Rembold, C.M.; Post, W.S. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: A consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2008, 21, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Cebrián, S.; González-Muniesa, P.; Milagro, F.I.; Martínez, J.A. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs in adipose tissue and obesity: Emerging roles as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuryłowicz, A.; Wicik, Z.; Owczarz, M.; Jonas, M.I.; Kotlarek, M.; Świerniak, M.; Lisik, W.; Jonas, M.; Noszczyk, B.; Puzianowska-Kuźnicka, M. NGS Reveals Molecular Pathways Affected by Obesity and Weight Loss-Related Changes in miRNA Levels in Adipose Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Yu, J.; Li, G.; Sun, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, H.; Hong, Z. MiR-27a promotes insulin resistance and mediates glucose metabolism by targeting PPAR-γ-mediated PI3K/AKT signaling. Aging 2019, 11, 7510–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortuza, R.; Feng, B.; Chakrabarti, S. miR-195 regulates SIRT1-mediated changes in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Qin, D.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Han, Q. MiR-195-5p Promotes Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy by Targeting MFN2 and FBXW7. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1580982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardu, C.; Trotta, M.C.; Pieretti, G.; Gatta, G.; Ferraro, G.; Nicoletti, G.F.; Onofrio, N.D.; Balestrieri, M.L.; Amico, M.D.; Abbatecola, A.; et al. MicroRNAs modulation and clinical outcomes at 1 year of follow-up in obese patients with pre-diabetes treated with metformin vs. placebo. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Kuosma, E.; Ferrie, J.E.; Luukkonen, R.; Nyberg, S.T.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Brunner, E.J.; Fransson, E.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Overweight, obesity, and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: Pooled analysis of individual-level data for 120,813 adults from 16 cohort studies from the USA and Europe. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e277–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saklayen, M.G. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rohde, K.; Keller, M.; la Cour Poulsen, L.; Blüher, M.; Kovacs, P.; Böttcher, Y. Genetics and epigenetics in obesity. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2019, 92, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallis, N.; Raffan, E. The Genetic Basis of Obesity and Related Metabolic Diseases in Humans and Companion Animals. Genes 2020, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Soskic, S.; Essack, M.; Arya, S.; Stewart, A.J.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Leptin and Obesity: Role and Clinical Implication. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 585887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzirad, R.; González-Muniesa, P.; Ghasemi, A. Hypoxia in Obesity and Diabetes: Potential Therapeutic Effects of Hyperoxia and Nitrate. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 5350267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiki, N.; Athyros, V.G.; Karagiannis, A.; Mikhailidis, D.P. Characteristics other than the diagnostic criteria associated with metabolic syndrome: An overview. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, M.; van Greevenbroek, M.M.; van der Kallen, C.J.; Ferreira, I.; Blaak, E.E.; Feskens, E.J.; Jansen, E.H.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Stehouwer, C.D. Low-grade inflammation can partly explain the association between the metabolic syndrome and either coronary artery disease or severity of peripheral arterial disease: The CODAM study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 39, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsalamandris, S.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Papamikroulis, G.-A.; Vogiatzi, G.; Papaioannou, S.; Deftereos, S.; Tousoulis, D. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetes: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Eur. Cardiol. 2019, 14, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Rosa, S.; Arcidiacono, B.; Chiefari, E.; Brunetti, A.; Indolfi, C.; Foti, D.P. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiovascular Disease: Genetic and Epigenetic Links. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E.; Toth, P.P.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Abate, N.; Aronne, L.J.; Brown, W.V.; Gonzalez-Campoy, J.M.; Jones, S.R.; Kumar, R.; La Forge, R.; et al. Obesity, adiposity, and dyslipidemia: A consensus statement from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2013, 7, 304–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguilera, C.M.; Gil-Campos, M.; Canete, R.; Gil, A. Alterations in plasma and tissue lipids associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Clin. Sci. 2008, 114, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Blaha, M.J.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; Deo, R.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Floyd, J.; Fornage, M.; Gillespie, C.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e146–e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navar-Boggan, A.M.; Peterson, E.D.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Neely, B.; Sniderman, A.D.; Pencina, M.J. Hyperlipidemia in early adulthood increases long-term risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation 2015, 131, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaric, B.; Obradovic, M.; Trpkovic, A.; Banach, M.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Isenovic, E.R. Endothelial Dysfunction in Dyslipidaemia: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macvanin, M.; Obradovic, M.; Zafirovic, S.; Stanimirovic, J.; Isenovic, E.R. The role of miRNAs in metabolic diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.A.; Stoian, A.P. Lipoproteins and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update on the Clinical Significance of Atherogenic Small, Dense LDL and New Therapeutical Options. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradovic, M.; Sudar, E.; Zafirovic, S.; Stanimirovic, J.; Labudovic-Borovic, M.; Isenovic, E.R. Estradiol in vivo induces changes in cardiomyocytes size in obese rats. Angiology 2015, 66, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solinas, G.; Karin, M. JNK1 and IKKbeta: Molecular links between obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Faseb J. 2010, 24, 2596–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stienstra, R.; Tack, C.J.; Kanneganti, T.D.; Joosten, L.A.; Netea, M.G. The inflammasome puts obesity in the danger zone. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, G.; Aroor, A.R.; Martinez-Lemus, L.A.; Sowers, J.R. Overnutrition, mTOR signaling, and cardiovascular diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2014, 307, R1198–R1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zafirovic, S.; Obradovic, M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Jovanovic, A.; Stanimirovic, J.; Stewart, A.J.; Pitt, S.J.; Isenovic, E.R. 17β-Estradiol protects against the effects of a high fat diet on cardiac glucose, lipid and nitric oxide metabolism in rats. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 446, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, H. Adipocytokines in obesity and metabolic disease. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 220, 13–0339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; Garcia-Cardena, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pignatelli, P.; Menichelli, D.; Pastori, D.; Violi, F. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease: New insights. Kardiol. Pol. 2018, 14, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toth, P.P. Insulin resistance, small LDL particles, and risk for atherosclerotic disease. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekic, J.; Zeljkovic, A. Atherosclerosis Development and Progression: The Role of Atherogenic Small, Dense LDL. Medicina 2022, 58, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treeck, O.; Buechler, C.; Ortmann, O. Chemerin and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buechler, C.; Feder, S.; Haberl, E.M.; Aslanidis, C. Chemerin Isoforms and Activity in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagpal, S.; Patel, S.; Jacobe, H.; DiSepio, D.; Ghosn, C.; Malhotra, M.; Teng, M.; Duvic, M.; Chandraratna, R.A. Tazarotene-induced gene 2 (TIG2), a novel retinoid-responsive gene in skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1997, 109, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, W.J.; Zabel, B.A.; Pachynski, R.K. Mechanisms and Functions of Chemerin in Cancer: Potential Roles in Therapeutic Intervention. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zabel, B.A.; Allen, S.J.; Kulig, P.; Allen, J.A.; Cichy, J.; Handel, T.M.; Butcher, E.C. Chemerin activation by serine proteases of the coagulation, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34661–34666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferland, D.J.; Mullick, A.E.; Watts, S.W. Chemerin as a Driver of Hypertension: A Consideration. Am. J. Hypertens. 2020, 33, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittamer, V.; Franssen, J.-D.; Vulcano, M.; Mirjolet, J.-F.; Le Poul, E.; Migeotte, I.; Brézillon, S.; Tyldesley, R.; Blanpain, C.; Detheux, M. Specific recruitment of antigen-presenting cells by chemerin, a novel processed ligand from human inflammatory fluids. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Oksvold, P.; Kampf, C.; Djureinovic, D.; Odeberg, J.; Habuka, M.; Tahmasebpoor, S.; Danielsson, A.; Edlund, K.; et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteom. MCP 2014, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwiecien, K.; Brzoza, P. The methylation status of the chemerin promoter region located from - 252 to + 258 bp regulates constitutive but not acute-phase cytokine-inducible chemerin expression levels. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzeczyńska-Moncznik, J.; Stefańska, A.; Zabel, B.A.; Kapińska-Mrowiecka, M.; Butcher, E.C.; Cichy, J. Chemerin and the recruitment of NK cells to diseased skin. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2009, 56, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachynski, R.K.; Wang, P.; Salazar, N.; Zheng, Y.; Nease, L.; Rosalez, J.; Leong, W.I.; Virdi, G.; Rennier, K.; Shin, W.J.; et al. Chemerin Suppresses Breast Cancer Growth by Recruiting Immune Effector Cells into the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niklowitz, P.; Rothermel, J.; Lass, N.; Barth, A.; Reinehr, T. Link between chemerin, central obesity, and parameters of the Metabolic Syndrome: Findings from a longitudinal study in obese children participating in a lifestyle intervention. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlee, S.D.; Ernst, M.C.; Muruganandan, S.; Sinal, C.J.; Goralski, K.B. Serum chemerin levels vary with time of day and are modified by obesity and tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2590–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bauer, S.; Wanninger, J.; Schmidhofer, S.; Weigert, J.; Neumeier, M.; Dorn, C.; Hellerbrand, C.; Zimara, N.; Schäffler, A.; Aslanidis, C.; et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) activation after excess triglyceride storage induces chemerin in hypertrophic adipocytes. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhu, R.; Yang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, D.; et al. Identification of chemerin as a novel FXR target gene down-regulated in the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muruganandan, S.; Parlee, S.D.; Rourke, J.L.; Ernst, M.C.; Goralski, K.B.; Sinal, C.J. Chemerin, a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) target gene that promotes mesenchymal stem cell adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 23982–23995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattern, A.; Zellmann, T.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Processing, signaling, and physiological function of chemerin. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Shen, W.-J.; Morser, J.; Leung, L.L. Dynamic and tissue-specific proteolytic processing of chemerin in obese mice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Zabel, B.A.; Myles, T.; Allen, S.J.; Handel, T.M.; Lee, P.P.; Butcher, E.C.; Leung, L.L. Regulation of chemerin bioactivity by plasma carboxypeptidase N, carboxypeptidase B (activated thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor), and platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, S.S.; Eisenberg, D.; Zhao, L.; Adams, C.; Leib, R.; Morser, J.; Leung, L. Chemerin activation in human obesity. Obesity 2016, 24, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferland, D.J.; Seitz, B.; Darios, E.S.; Thompson, J.M.; Yeh, S.T.; Mullick, A.E.; Watts, S.W. Whole-Body but Not Hepatic Knockdown of Chemerin by Antisense Oligonucleotide Decreases Blood Pressure in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 365, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Leung, L.L.; Morser, J. Chemerin Forms: Their Generation and Activity. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Bury, L.; Gresele, P.; Berube, C.; Leung, L.L.; Morser, J. Prochemerin cleavage by factor XIa links coagulation and inflammation. Blood 2018, 131, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watts, S.W.; Dorrance, A.M.; Penfold, M.E.; Rourke, J.L.; Sinal, C.J.; Seitz, B.; Sullivan, T.J.; Charvat, T.T.; Thompson, J.M.; Burnett, R.; et al. Chemerin connects fat to arterial contraction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darios, E.S.; Winner, B.M.; Charvat, T.; Krasinksi, A.; Punna, S.; Watts, S.W. The adipokine chemerin amplifies electrical field-stimulated contraction in the isolated rat superior mesenteric artery. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2016, 311, H498–H507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, A.J.; Yang, P.; Read, C.; Kuc, R.E.; Yang, L.; Taylor, E.J.; Taylor, C.W.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P. Chemerin Elicits Potent Constrictor Actions via Chemokine-Like Receptor 1 (CMKLR1), not G-Protein-Coupled Receptor 1 (GPR1), in Human and Rat Vasculature. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e004421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muruganandan, S.; Roman, A.A.; Sinal, C.J. Role of chemerin/CMKLR1 signaling in adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis of bone marrow stem cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondue, B.; Wittamer, V.; Parmentier, M. Chemerin and its receptors in leukocyte trafficking, inflammation and metabolism. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-L.; Ren, L.-R.; Sun, L.-F.; Huang, C.; Xiao, T.-X.; Wang, B.-B.; Chen, J.; Zabel, B.A.; Ren, P.; Zhang, J.V. The role of GPR1 signaling in mice corpus luteum. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zabel, B.A.; Nakae, S.; Zúñiga, L.; Kim, J.-Y.; Ohyama, T.; Alt, C.; Pan, J.; Suto, H.; Soler, D.; Allen, S.J. Mast cell–expressed orphan receptor CCRL2 binds chemerin and is required for optimal induction of IgE-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2207–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Henau, O.; Degroot, G.-N.; Imbault, V.; Robert, V.; De Poorter, C.; McHeik, S.; Galés, C.; Parmentier, M.; Springael, J.-Y. Signaling Properties of Chemerin Receptors CMKLR1, GPR1 and CCRL2. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rourke, J.L.; Muruganandan, S.; Dranse, H.J.; McMullen, N.M.; Sinal, C.J. Gpr1 is an active chemerin receptor influencing glucose homeostasis in obese mice. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 222, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, T.F.; Czerniak, A.S.; Weiß, T.; Schoeder, C.T.; Wolf, P.; Seitz, O.; Meiler, J.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Ligand-binding and -scavenging of the chemerin receptor GPR1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6265–6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotti, C.; Gagliostro, V.; Bosisio, D.; Del Prete, A.; Tiberio, L.; Thelen, M.; Sozzani, S. The atypical receptor CCRL2 (CC Chemokine Receptor-Like 2) does not act as a decoy receptor in endothelial cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schioppa, T.; Sozio, F.; Barbazza, I.; Scutera, S.; Bosisio, D.; Sozzani, S.; Del Prete, A. Molecular Basis for CCRL2 Regulation of Leukocyte Migration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 615031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, B.A.; Zuniga, L.; Ohyama, T.; Allen, S.J.; Cichy, J.; Handel, T.M.; Butcher, E.C. Chemoattractants, extracellular proteases, and the integrated host defense response. Exp. Hematol. 2006, 34, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yu, F.; Xiong, Y.; Wei, W.; Ma, H.; Nisi, F.; Song, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, D.; Yuan, G.; et al. Chemerin enhances the adhesion and migration of human endothelial progenitor cells and increases lipid accumulation in mice with atherosclerosis. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, M.; Edinger, A.L.; Stordeur, P.; Rucker, J.; Verhasselt, V.; Sharron, M.; Govaerts, C.; Mollereau, C.; Vassart, G.; Doms, R.W.; et al. ChemR23, a putative chemoattractant receptor, is expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages and is a coreceptor for SIV and some primary HIV-1 strains. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998, 28, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, B.A.; Silverio, A.M.; Butcher, E.C. Chemokine-like receptor 1 expression and chemerin-directed chemotaxis distinguish plasmacytoid from myeloid dendritic cells in human blood. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamawaki, H.; Kameshima, S.; Usui, T.; Okada, M.; Hara, Y. A novel adipocytokine, chemerin exerts anti-inflammatory roles in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 423, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Adya, R.; Tan, B.K.; Chen, J.; Randeva, H.S. Identification of chemerin receptor (ChemR23) in human endothelial cells: Chemerin-induced endothelial angiogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozaoglu, K.; Curran, J.E.; Stocker, C.J.; Zaibi, M.S.; Segal, D.; Konstantopoulos, N.; Morrison, S.; Carless, M.; Dyer, T.D.; Cole, S.A.; et al. Chemerin, a novel adipokine in the regulation of angiogenesis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 2476–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferland, D.J.; Watts, S.W. Chemerin: A comprehensive review elucidating the need for cardiovascular research. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 99, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neves, K.B.; Lobato, N.S.; Lopes, R.A.; Filgueira, F.P.; Zanotto, C.Z.; Oliveira, A.M.; Tostes, R.C. Chemerin reduces vascular nitric oxide/cGMP signalling in rat aorta: A link to vascular dysfunction in obesity? Clin. Sci. 2014, 127, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didion, S.P.; Heistad, D.D.; Faraci, F.M. Mechanisms That Produce Nitric Oxide–Mediated Relaxation of Cerebral Arteries during Atherosclerosis. Stroke 2001, 32, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siragusa, M.; Fleming, I. The eNOS signalosome and its link to endothelial dysfunction. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2016, 468, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, L. Role of Chemerin/ChemR23 axis as an emerging therapeutic perspective on obesity-related vascular dysfunction. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N.; Naruse, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Miyabe, M.; Saiki, T.; Enomoto, A.; Takahashi, M.; Matsubara, T. Chemerin promotes angiogenesis in vivo. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corre, I.; Paris, F.; Huot, J. The p38 pathway, a major pleiotropic cascade that transduces stress and metastatic signals in endothelial cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 55684–55714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luangsay, S.; Wittamer, V.; Bondue, B.; De Henau, O.; Rouger, L.; Brait, M.; Franssen, J.D.; de Nadai, P.; Huaux, F.; Parmentier, M. Mouse ChemR23 is expressed in dendritic cell subsets and macrophages, and mediates an anti-inflammatory activity of chemerin in a lung disease model. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6489–6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Haybar, H.; Shahrabi, S.; Rezaeeyan, H.; Shirzad, R.; Saki, N. Endothelial Cells: From Dysfunction Mechanism to Pharmacological Effect in Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2019, 19, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.K.; Kaur, J.; Adya, R.; Miras, A.D.; Mattu, H.S.; Hattersley, J.G.; Kaltsas, G.; Tan, B.K.; Randeva, H.S. Chemerin induces endothelial cell inflammation: Activation of nuclear factor-kappa beta and monocyte-endothelial adhesion. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16678–16690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neves, K.B.; Nguyen Dinh Cat, A.; Lopes, R.A.; Rios, F.J.; Anagnostopoulou, A.; Lobato, N.S.; de Oliveira, A.M.; Tostes, R.C.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Chemerin Regulates Crosstalk Between Adipocytes and Vascular Cells Through Nox. Hypertension 2015, 66, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, K.; Friebe, D.; Ullrich, T.; Kratzsch, J.; Dittrich, K.; Herberth, G.; Adams, V.; Kiess, W.; Erbs, S.; Körner, A. Chemerin as a mediator between obesity and vascular inflammation in children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E556–E564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, W.; Tian, C.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Gao, P.; Liu, J. Oxidative stress mediates chemerin-induced autophagy in endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 55, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Mei, X.; Chen, S.Y. Smooth Muscle Cells in Vascular Remodeling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, e247–e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Cai, W.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Tang, X. Chemerin stimulates aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration via activation of autophagy in VSMCs of metabolic hypertension rats. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Kunimoto, H.; Kazama, K.; Takai, M.; Oda, M.; Okada, M.; Yamawaki, H. Chemerin promotes the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle and increases mouse blood pressure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 309, H1017–H1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanthazi, A.; Jespers, P.; Vegh, G.; Dubois, C.; Hubesch, G.; Springael, J.Y.; Dewachter, L.; Mc Entee, K. Chemerin Added to Endothelin-1 Promotes Rat Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Migration. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Z.; Yang, B.; Yi, J.; Zhu, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Hussain, R.; et al. Exposure to Fluoride induces apoptosis in liver of ducks by regulating Cyt-C/Caspase 3/9 signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 224, 112662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, K.; Nigro, P.; Berk, B.C. Oxidative stress and vascular smooth muscle cell growth: A mechanistic linkage by cyclophilin A. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, S.; Zhang, E.; Senapati, P.; Amaram, V.; Reddy, M.A.; Stapleton, K.; Leung, A.; Lanting, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; et al. A Novel Angiotensin II-Induced Long Noncoding RNA Giver Regulates Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Proliferation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, X.; Sun, B.; Zhao, S. Mitoquinone attenuates vascular calcification by suppressing oxidative stress and reducing apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells via the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Schurgers, L.J.; Shiels, P.G.; Stenvinkel, P. Early vascular ageing in chronic kidney disease: Impact of inflammation, vitamin K, senescence and genomic damage. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, ii31–ii37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Er, L.K.; Hsu, L.A. Circulating Chemerin Levels, but not the RARRES2 Polymorphisms, Predict the Long-Term Outcome of Angiographically Confirmed Coronary Artery Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eichelmann, F.; Schulze, M.B.; Wittenbecher, C.; Menzel, J.; Weikert, C.; di Giuseppe, R.; Biemann, R.; Isermann, B.; Fritsche, A.; Boeing, H.; et al. Chemerin as a Biomarker Linking Inflammation and Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, C.G.; Spiroglou, S.G.; Varakis, J.N.; Apostolakis, E.; Papadaki, H.H. Chemerin and CMKLR1 expression in human arteries and periadventitial fat: A possible role for local chemerin in atherosclerosis? BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2014, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, P.H.; Tsang, L.; Woodiwiss, A.J.; Norton, G.R.; Solomon, A. Circulating concentrations of the novel adipokine chemerin are associated with cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 41, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Q. Association of serum chemerin concentrations with the presence of atrial fibrillation. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 54, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Tao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Qian, Z.; Lu, X. Serum Chemerin as a Novel Prognostic Indicator in Chronic Heart Failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kammerer, A.; Staab, H.; Herberg, M.; Kerner, C.; Klöting, N.; Aust, G. Increased circulating chemerin in patients with advanced carotid stenosis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2018, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Müssig, K.; Staiger, H.; Machicao, F.; Thamer, C.; Machann, J.; Schick, F.; Claussen, C.D.; Stefan, N.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U. RARRES2, encoding the novel adipokine chemerin, is a genetic determinant of disproportionate regional body fat distribution: A comparative magnetic resonance imaging study. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2009, 58, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministrini, S.; Ricci, M.A.; Nulli Migliola, E.; De Vuono, S.; D’Abbondanza, M.; Paganelli, M.T.; Vaudo, G.; Siepi, D.; Lupattelli, G. Chemerin predicts carotid intima-media thickening in severe obesity. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 50, e13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Dayem, S.M.; Battah, A.A.; El Bohy Ael, M.; El Shehaby, A.; El Ghaffar, E.A. Relationship of plasma level of chemerin and vaspin to early atherosclerotic changes and cardiac autonomic neuropathy in adolescent type 1 diabetic patients. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. JPEM 2015, 28, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, Z.; Kelishadi, R.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J. The comparison of chemerin, adiponectin and lipid profile indices in obese and non-obese adolescents. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2016, 10, S43–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hah, Y.J.; Kim, N.K.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, H.S.; Hur, S.H.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, Y.N.; Park, K.G. Relationship between Chemerin Levels and Cardiometabolic Parameters and Degree of Coronary Stenosis in Korean Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Diabetes Metab. J. 2011, 35, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molina Mdel, C.; Faria, C.P.; Montero, M.P.; Cade, N.V.; Mill, J.G. Cardiovascular risk factors in 7-to-10-year-old children in Vitória, Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 2010, 26, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferranti, S.D.d.; Steinberger, J.; Ameduri, R.; Baker, A.; Gooding, H.; Kelly, A.S.; Mietus-Snyder, M.; Mitsnefes, M.M.; Peterson, A.L.; St-Pierre, J.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in High-Risk Pediatric Patients: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e603–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.-S.; Jiang, H.; Xie, Y.; Wei, Q.-P.; Yin, X.-F.; Ye, J.-H.; Quan, X.-Z.; Lan, Y.-L.; Zhao, M.; Tian, X.-L.; et al. Chemerin promotes the pathogenesis of preeclampsia by activating CMKLR1/p-Akt/CEBPα axis and inducing M1 macrophage polarization. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2022, 38, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Hong, Z.; Xia, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L. Analysis of the expression levels of chemerin, ox-LDL, MMP-9, and PAPP-A in ICVD patients and their relationship with the severity of neurological impairment. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Q.; Lin, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yu, K.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, L.; Shi, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Chang, C.; et al. Chemerin is a novel biomarker of acute coronary syndrome but not of stable angina pectoris. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gu, P.; Cheng, M.; Hui, X.; Lu, B.; Jiang, W.; Shi, Z. Elevating circulation chemerin level is associated with endothelial dysfunction and early atherosclerotic changes in essential hypertensive patients. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, M.; Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Januś, D.; Furtak, A.; Małek, A.; Sztefko, K.; Starzyk, J.B. Circulating chemerin level may be associated with early vascular pathology in obese children without overt arterial hypertension—Preliminary results. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. JPEM 2020, 33, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.D. Neural control of the circulation. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2011, 35, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omori, A.; Goshima, M.; Kakuda, C.; Kodama, T.; Otani, K.; Okada, M.; Yamawaki, H. Chemerin-9-induced contraction was enhanced through the upregulation of smooth muscle chemokine-like receptor 1 in isolated pulmonary artery of pulmonary arterial hypertensive rats. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, K.; Canpolat, U.; Akın, Ş.; Dural, M.; Karakaya, J.; Aytemir, K.; Özer, N.; Gürlek, A. Chemerin is not associated with subclinical atherosclerosis markers in prediabetes and diabetes. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2016, 16, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zylla, S.; Dörr, M.; Völzke, H.; Schminke, U.; Felix, S.B.; Nauck, M.; Friedrich, N. Association of Circulating Chemerin with Subclinical Parameters of Atherosclerosis: Results of a Population-Based Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yu, K.; Wu, B.; Zhong, Y.; Zeng, Q. The elevated levels of plasma chemerin and C-reactive protein in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi = Chin. J. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 31, 953–956. [Google Scholar]

- Aronis, K.N.; Sahin-Efe, A.; Chamberland, J.P.; Spiro, A., 3rd; Vokonas, P.; Mantzoros, C.S. Chemerin levels as predictor of acute coronary events: A case-control study nested within the veterans affairs normative aging study. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2014, 63, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghetti, G.; von Lewinski, D.; Eaton, D.M.; Sourij, H.; Houser, S.R.; Wallner, M. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Current and Future Therapies. Beyond Glycemic Control. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Guo, B.; Chang, L.; Li, Y. Chemerin Induces Insulin Resistance in Rat Cardiomyocytes in Part through the ERK1/2 Signaling Pathway. Pharmacology 2014, 94, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamparter, J.; Raum, P.; Pfeiffer, N.; Peto, T.; Höhn, R.; Elflein, H.; Wild, P.; Schulz, A.; Schneider, A.; Mirshahi, A. Prevalence and associations of diabetic retinopathy in a large cohort of prediabetic subjects: The Gutenberg Health Study. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2014, 28, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, L.-L.; Song, H. Chemerin promotes microangiopathy in diabetic retinopathy via activation of ChemR23 in rat primary microvascular endothelial cells. Mol. Vis. 2021, 27, 575–587. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Penas, D.; Feijóo-Bandín, S.; García-Rúa, V.; Mosquera-Leal, A.; Durán, D.; Varela, A.; Portolés, M.; Roselló-Lletí, E.; Rivera, M.; Diéguez, C.; et al. The Adipokine Chemerin Induces Apoptosis in Cardiomyocytes. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Sagara, A.; Otani, K.; Okada, M.; Yamawaki, H. Chemerin-9 stimulates migration in rat cardiac fibroblasts in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 912, 174566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Fu, C.; Liu, W.; Liang, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Sheng, Q.; Liu, P. Chemerin-induced angiogenesis and adipogenesis in 3 T3-L1 preadipocytes is mediated by lncRNA Meg3 through regulating Dickkopf-3 by sponging miR-217. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 385, 114815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferland, D.J.; Garver, H.; Contreras, G.A.; Fink, G.D.; Watts, S.W. Chemerin contributes to in vivo adipogenesis in a location-specific manner. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watts, S.W.; Darios, E.S.; Mullick, A.E.; Garver, H.; Saunders, T.L.; Hughes, E.D.; Filipiak, W.E.; Zeidler, M.G.; McMullen, N.; Sinal, C.J.; et al. The chemerin knockout rat reveals chemerin dependence in female, but not male, experimental hypertension. Faseb J. 2018, 32, fj201800479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, E.D.; Watts, S.W. Endogenous Chemerin from PVAT Amplifies Electrical Field-Stimulated Arterial Contraction: Use of the Chemerin Knockout Rat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vorst, E.P.C.; Mandl, M.; Müller, M.; Neideck, C.; Jansen, Y.; Hristov, M.; Gencer, S.; Peters, L.J.F.; Meiler, S.; Feld, M.; et al. Hematopoietic ChemR23 (Chemerin Receptor 23) Fuels Atherosclerosis by Sustaining an M1 Macrophage-Phenotype and Guidance of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells to Murine Lesions-Brief Report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Xiong, W.; Luo, Y.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Cao, Y.; Dong, S. Adipokine Chemerin Stimulates Progression of Atherosclerosis in ApoE(-/-) Mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7157865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachine, N.A.; Elnekiedy, A.A.; Megallaa, M.H.; Khalil, G.I.; Sadaka, M.A.; Rohoma, K.H.; Kassab, H.S. Serum chemerin and high-sensitivity C reactive protein as markers of subclinical atherosclerosis in Egyptian patients with type 2 diabetes. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 7, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, K.B.; Nguyen Dinh Cat, A.; Alves-Lopes, R.; Harvey, K.Y.; Costa, R.M.D.; Lobato, N.S.; Montezano, A.C.; Oliveira, A.M.; Touyz, R.M.; Tostes, R.C. Chemerin receptor blockade improves vascular function in diabetic obese mice via redox-sensitive and Akt-dependent pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H1851–H1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jannaway, M.; Torrens, C.; Warner, J.A.; Sampson, A.P. Resolvin E1, resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 inhibit constriction of rat thoracic aorta and human pulmonary artery induced by the thromboxane mimetic U46619. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralski, K.B.; Sinal, C.J. Elucidation of chemerin and chemokine-like receptor-1 function in adipocytes by adenoviral-mediated shRNA knockdown of gene expression. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 460, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Teng, R.J.; Guan, T.; Eis, A.; Kaul, S.; Konduri, G.G.; Shi, Y. Role of autophagy in angiogenesis in aortic endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012, 302, C383–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carracedo, M.; Artiach, G.; Arnardottir, H.; Bäck, M. The resolution of inflammation through omega-3 fatty acids in atherosclerosis, intimal hyperplasia, and vascular calcification. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bäck, M.; Hansson, G.K. Omega-3 fatty acids, cardiovascular risk, and the resolution of inflammation. Faseb J. 2019, 33, 1536–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasturk, H.; Abdallah, R.; Kantarci, A.; Nguyen, D.; Giordano, N.; Hamilton, J.; Van Dyke, T.E. Resolvin E1 (RvE1) Attenuates Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation in Diet and Inflammation-Induced Atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carracedo, M.; Artiach, G.; Witasp, A.; Clària, J.; Carlström, M.; Laguna-Fernandez, A.; Stenvinkel, P.; Bäck, M. The G-protein coupled receptor ChemR23 determines smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching to enhance high phosphate-induced vascular calcification. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sato, K.; Yoshizawa, H.; Seki, T.; Shirai, R.; Yamashita, T.; Okano, T.; Shibata, K.; Wakamatsu, M.J.; Mori, Y.; Morita, T. Chemerin-9, a potent agonist of chemerin receptor (ChemR23), prevents atherogenesis. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 1779–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Han, C. Chemerin-9 Attenuates Experimental Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Formation in ApoE(-/-) Mice. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 6629204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ge, X.; Robinson, W.H.; Morser, J. Chemerin 156F, generated by chymase cleavage of prochemerin, is elevated in joint fluids of arthritis patients. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spirk, M.; Zimny, S.; Neumann, M.; McMullen, N.; Sinal, C.J.; Buechler, C. Chemerin-156 is the Active Isoform in Human Hepatic Stellate Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferland, D.J.; Flood, E.D.; Garver, H.; Yeh, S.T.; Riney, S.; Mullick, A.E.; Fink, G.D.; Watts, S.W. Different blood pressure responses in hypertensive rats following chemerin mRNA inhibition in dietary high fat compared to dietary high-salt conditions. Physiol. Genom. 2019, 51, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient’s Gender and Age (Mean ± SD or Median and Range) | CVDs | Chemerin Levels | CV- Associated Disorders/Parameters and Chemerin Correlation | Reference |

| male and female 11.6 ± 2.0 | ↑ BMI | ↑ (serum) | BMI, waist circumference, leptin, body fat insulin, HDL-C and TC | [85] |

| male and female 48.4 ± 10.9 | dyslipidemia, hypertension | ↑ (plasma) | RARRES2 gene polymorphism, hs-CRP | [138] |

| male and female 43.5 ± 13.0 | rheumatoid factor-positive, hypertension | ↑ (plasma) | Hs-CRP, leptin, vascular adhesion molecule, monocyte chemoattractant protein | [141] |

| male and female 60.54 ± 9.64 | arterial fibrillation | ↑ (serum) | arterial fibrillation, BMI, SBP, DBP, TC, LDL-C, creatinine, hs-CRP and left atrial diameter | [142] |

| male and female 66 (58–75) | hypertension, chronic heart failure, diabetes, hyperlipidemia | ↑ (serum) | heart failure, diabetes, hs-CRP, hypertension | [143] |

| male and female 66.9 ± 0.6 | coronary artery disease | ↑ (plasma) | TC, hsCRP, peripheral leukocyte count, TNF-α | [144] |

| male and female 45.5 (18–69) | ↑ BMI, impaired glucose tolerance | ↑RARRES2 expression (whole blood) | visceral fat mass | [145] |

| male and female 44.0 ± 10.1 | hypertension, diabetes, ↑ BMI | ↑ (plasma) | waist circumference, HOMA-IR, fat mass, HbA1c, cIMT | [146] |

| male and female 16.3 ± 1.5 | atherosclerotic lesions and cardiac autonomic neuropathy, diabetes type 1 | ↑ (serum) | vaspin and LDL-C | [147] |

| female 13.9 ± 1.8 | ↑ BMI | ↑ (serum) | TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and fat mass | [148] |

| male and female 62.2 ± 10.0 | coronary stenosis, hypertension, diabetes | ↑ (serum) | fasting glucose, TC, LDL-C, hs-CRP, degree of coronary artery stenosis | [149] |

| Cell Culture Model | Chemerin Concentrations | Duration of Stimulation | CV-Associated Disorders/Parameters–Chemerin Correlation | Reference |

| human microvascular endothelial cells | 10 nM | 2 h | ↑ endothelial cell adhesion, protein expression and secretion, activates NF-KB | [125] |

| human microvascular endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells | 50 ng/mL | 5, 15, 30, 60 min and 2, 8, 24 h | ↑ O2·−, ↑ H2O2, ↑ Nox 1, ↑ Nox 4 and ↑ miRNA expression, ↑ phosphorylation of SAPK/JNK and ERK1/2, ↓ eNOS, ↓ NO and apoptosis | [126] |

| human peripheral blood mononuclear cells | 2.5, 25, 50 and 100 ng/mL | 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. | ↑ adhesion and migration abilities of endothelial progenitor cells | [138] |

| Animals (Gender) | Tissues | CV-Associated Disorders/Parameters–Chemerin Correlation | Reference | |

| chemerin knockout Sprague Dawley rat (female) | thoracic aorta | blood pressure modification | [171] | |

| chemerin knockout Sprague Dawley rat (female) | plasma, mesenteric adipocytes | ↓ visceral adiposity | [170] | |

| chemerin knockout Sprague Dawley rat (female) | superior mesenteric arteries | ↓ vascular tone | [172] | |

| Cell Culture Model | Chemerin Concentrations | Duration of Stimulation | CV-Associated Disorders/Parameters–Chemerin Correlation | Reference |

| rat vascular smooth muscle cells | 1–300 ng/mL | 24 h | ↑ vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration | [131] |

| Sprague Dawley rat’s cardiomyocytes | 10 and 100 ng/mL | 24 h | impaired insulin signalling and induced insulin resistance | [164] |

| Sprague Dawley rat’s cardiomyocytes | 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 nM | 6–48 h | cardiomyocytes apoptosis | [167] |

| mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocytes | 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 ng/mL | 48 h | miRNA-217 suppression (correlated with fat accumulation), induced preadipocytes differentiation into adipocytes, ↑ Meg3 lncRNA | [169] |

| Wistar rat’s cardiac fibroblasts | 100 ng/mL | 12 h | fibroblast migration, ↑ ROS | [168] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macvanin, M.T.; Rizzo, M.; Radovanovic, J.; Sonmez, A.; Paneni, F.; Isenovic, E.R. Role of Chemerin in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112970

Macvanin MT, Rizzo M, Radovanovic J, Sonmez A, Paneni F, Isenovic ER. Role of Chemerin in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(11):2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112970

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacvanin, Mirjana T., Manfredi Rizzo, Jelena Radovanovic, Alper Sonmez, Francesco Paneni, and Esma R. Isenovic. 2022. "Role of Chemerin in Cardiovascular Diseases" Biomedicines 10, no. 11: 2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112970