Fluorescence Sensors Based on Hydroxycarbazole for the Determination of Neurodegeneration-Related Halide Anions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Information

2.2. Synthesis

2.3. Spectrofluorimetric Study of Sensors

2.3.1. General Procedure

2.3.2. Solvatochromic Effect Study

2.3.3. Excited-State Proton Transfer Reactions in Organic and Aqueous Solvents

2.4. Anion Sensing and Recognition

2.5. Fluoride and Chloride Determination in Real Samples by Using 1-Hydroxycarbazole (2c) as Fluorescence Sensor

2.6. Study of the Anion Interaction by NMR

2.7. Computational Studies of the Anion Chemosensor by Molecular Modelling

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Fluorescence Behaviour of Carbazole Derivatives

3.3. Excited-State Proton Transfer (ESPT) Reactions of Carbazole Derivatives

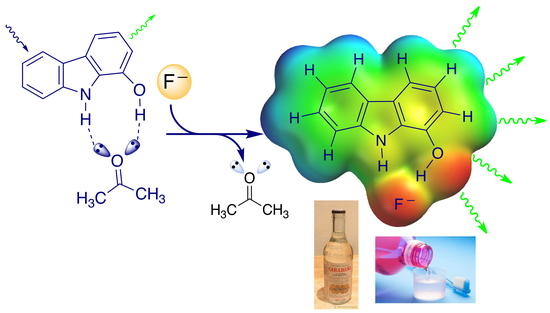

3.4. Anion Sensing and Recognition

3.5. Determination of the Affinity Constants Anion–Sensor 2c

3.6. Anion Recognition Studies by 1H-NMR

3.7. Molecular Modelling Studies

3.8. Analytical Application of 2c as “Turn-On” Fluorescence Sensor

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goschorska, M.; Gutowska, I.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Piotrowska, K.; Metryka, E.; Safranow, K.; Chlubek, D. Influence of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors Used in Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment on the Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes and the Concentration of Glutathione in THP-1 Macrophages under Fluoride-Induced Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, P.; Mojumder, D.; De Toledo, J.; Lucius, R.; Wilms, H. Pathophysiological processes in multiple sclerosis: Focus on nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 and emerging pathways. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. ROS in cancer: The burning question. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Perry, G.; Lee, H.; Zhu, X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goschorska, M.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Gutowska, I.; Metryka, E.; Skórka-Majewicz, M.; Chlubek, D. Potential Role of Fluoride in the Etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, A.; Portero-Otin, M.; Pamplona, R.; Ferrer, I. Protein Targets of oxidative damage in human neurodegenerative diseases with abnormal protein aggregates. Brain Pathol. 2010, 20, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, A.; Ringer, C.; Bilkei-Gorzo, A.; Weihe, E.; Roeper, J.; Schütz, B. Downregulation of the Potassium Chloride Cotransporter KCC2 in Vulnerable Motoneurons in the SOD1-G93A Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozovaya, N.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Hammond, C. Striatal dual cholinergic/GABAergic transmission in Parkinson disease: Friends or foes? Cell Stress 2018, 2, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnárovits, L.; Takács, E. Rate constants of dichloride radical anion reactions with molecules of environmental interest in aqueous solution: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 41552–41575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, L.; Yin, Z.; Song, X.; Ruan, T.; Hua, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Ning, H. Fluoride-induced alterations of synapse-related proteins in the cerebral cortex of ICR offspring mouse brain. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.; Siddiqi, M.H.; Khan, K.; Zahra, K.; Naqvi, A.N. Haematological evaluation of sodium fluoride toxicity in oryctolagus cuniculus. Toxicol. Rep. 2017, 4, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Smith, K.D.; Davis, J.H.; Gordon, P.B.; Breaker, R.R.; Strobel, S.A. Eukaryotic resistance to fluoride toxicity mediated by a widespread family of fluoride export proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19018–19023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duvva, L.K.; Panga, K.K.; Dhakate, R.; Himabindu, V. Health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride toxicity in ground water contamination in the semi-arid area of Medchal, South India. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, N.R.; Strobel, S.A. Principles of fluoride toxicity and the cellular response: A review. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Mukherjee, K.; Ghosh, S.K.; Saha, B. Sources and toxicity of fluoride in the environment. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 2881–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearcy, K.; Elphick, J.; Burnett-Seidel, C. Toxicity of fluoride to aquatic species and evaluation of toxicity modifying factors. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 1642–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, O.; Arreola-Mendoza, L.; Del Razo, L.M. Molecular mechanisms of fluoride toxicity. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2010, 188, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russ, T.C.; Killin, L.O.J.; Hannah, J.; Batty, G.D.; Deary, I.J.; Starr, J.M. Aluminium and fluoride in drinking water in relation to later dementia risk. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 216, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinawy, A.A. Synergistic oxidative impact of aluminum chloride and sodium fluoride exposure during early stages of brain development in the rat. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 10951–10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhi, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Xia, H.; Liu, X. Light-emitting conjugated microporous polymers based on excited- state intramolecular proton transfer strategy and selective switch- off sensing of anions. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 3040–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, S.; Xu, L.; Feng, X. Fluoride anion sensing mechanism of 2-(quinolin-2-yl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one chemosensor based on inhibition of excited state intramolecular ultrafast proton transfer. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2020, 33, e4116–e4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.-W.; Wang, F.; Liang, Y.-H. TDDFT study on the sensing mechanism of a fluorescent sensor for fluoride anion: Inhibition of the ESPT process. Spectrochim. Acta A 2015, 149, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagaraj, K.; Pitchumani, K. Highly Selective “Turn-On” Fluorescent and Colorimetric Sensing of Fluoride Ion Using 2-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydroquinolin-4(1H)-one based on Excited-State Proton Transfer. Chem.–Asian J. 2014, 9, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, A.; Purkayastha, P.; Chattopadhyay, N. Photoprocesses of excited molecules in confined liquid environments: An overview. J. Photoch. Photobiol. C 2007, 8, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Goswami, S. 2-Hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde: A versatile building block for the development of sensors in supramolecular chemistry and molecularrecognition. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 2017, 245, 1062–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, L.; Licchelli, M.; Perotti, A.; Poggi, A.; Rabaioli, G.; Sacchi, D.; Taglietti, A. Fluorescent molecular sensing of amino acids bearing an aromatic residue. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2001, 2, 2108–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, L.; Poggi, A. Anion recognition by coordinative interactions:metal–amine complexes as receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1681–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibrandi, G.; Amendola, V.; Bergamaschi, G.; Fabbrizzi, L.; Licchelli, M. Bistren cryptands and cryptates: Versatile receptors for anion inclusion and recognition in water. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 3510–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Du, J.; Hu, M.; Fan, J.; Peng, X. Fluorescent chemodosimeters using “mild” chemical events for the detection of small anions and cations in biological and environmental media. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4511–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, P.A.; Caltagirone, C. Anion sensing by small molecules and molecular ensembles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4212–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Kim, J.S.; Sessler, J.L. Small molecule-based ratiometric fluorescence probes for cations, anions, and biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4185–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xie, Y. Fluorescent and colorimetric ion probes based on conjugated oligopyrroles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Huang, L.; Shen, Q.; Yang, N.-D.; Pu, C.; Shao, J.; Li, L.; Yu, C.; Huang, W. Small-molecule fluorescent probes based on covalent assembly strategy for chemoselective bioimaging. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 1393–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, B.; Kim, B.; Zhang, Y.; Frazer, A.; Belfield, K.D. Highly selective fluorescence turn-on sensor for fluoride detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter 2013, 5, 2920–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Yoon, J. Fluorescence and Colorimetric Chemosensors for Fluoride-Ion Detection. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5511–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, P.A. Synthetic indole, carbazole, biindole and indolocarbazole-based receptors: Applications in anion complexation and sensing. Chem. Commun. 2008, 4525–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, G.E. Fluorescence quenching of carbazoles. J. Phys. Chem. 1980, 84, 2940–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, N. Excited state proton transfer of carbazole. A convenient way to study microheterogeneous environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2003, 4, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, L.; Jammi, S.; Punniyamurthy, T. Novel CuO nanoparticle catalyzed C–N cross coupling of amines with iodobenzene. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3397–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, R.B.; Betham, M. N-H Carbazole Synthesis from 2-Chloroanilines via Consecutive Amination and C–H Activation. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 9403–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Rewcastle, G.W.; Vazquez de Miguel, L.M. Improved syntheses of substituted carbazoles and benzocarbazoles via lithiation of the (dialkylamino) methyl (aminal) derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, K.A. Binding Constants. In The Measurement of Molecular Complex Stability; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kubik, S. Anion recognition in water. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3648–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, P.A.; Howea, E.N.W.; Wua, X.; Spooner, M.J. Anion receptor chemistry: Highlights from 2016. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 375, 333–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschaert, N.; Caltagirone, C.; Van Rossom, W.; Gale, P.A. Applications of Supramolecular Anion Recognition. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8038–8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.-F.; Wang, J.-H.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Y.-B. Anion complexation and sensing using modified urea and thiourea-based receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3729–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaur, N.; Kaur, G.; Fegade, U.A.; Singh, A.; Sahoo, S.K.; Kuwar, A.S.; Singh, N. Anion sensing with chemosensors having multiple NH recognition units. TrAC-Trend Anal. Chem. 2017, 95, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.H.R.; Donnelly, D.M.X.; Finet, J.-P.; Guiry, P.J. Aryllead triacetates: Regioselective reagents for N-arylation of amines. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1991, 1, 2095–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, V.; Martín, M.A.; Menéndez, J.C. Synthesis of Oxygenated Carbazoles by Palladium-Mediated Oxidative Double C-H Activation of Diarylamines Assisted by Microwave Irradiation. Synlett 2006, 2375–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, V.; Martín, M.A.; Menéndez, J.C. Acid-Free Synthesis of Carbazoles and Carbazolequinones by IntramolecularPd-Catalyzed, Microwave-Assisted Oxidative Biaryl Coupling Reactions–Efficient Syntheses of Murrayafoline A, 2-Methoxy-3-methylcarbazole, and Glycozolidine. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2009, 4614–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illos, R.A.; Shamir, D.; Shimon, L.J.W.; Zilbermann, I.; Bittner, S. N-Dansyl-carbazoloquinone: A chemical and electrochemical fluorescent switch. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 5543–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohne, C.; Ihmels, H.; Waidelich, M.; Yihwa, C. N-acylureido functionality as acceptor substituent in solvatochromic fluorescence probes: Detection of carboxylic acids, alcohols, and fluoride ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17158–17159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonesi, S.M.; Erra-Balsells, R. Electronic spectroscopy of carbazole and N-and C-substituted carbazoles in homogeneous media and in solid matrix. J. Lumin. 2001, 93, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Chattopadhyay, N.; Nath, D.; Kundu, T.; Chowdhury, M. Excited-state proton transfer kinetics of carbazole. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1985, 121, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbai, M.; Ait Lyazidi, S.; Lerner, D.A.; del Castillo, B.; Martín, M.A. Modified β-cylclodextrins as enhancers of fluorescence emission of carbazole alkaloid derivatives. Anal. Chim. Acta 1995, 303, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denekamp, C.; Suwinska, K.; Salman, H.; Abraham, Y.; Eichen, Y.; Ari, J.B. Anion-Binding Properties of the Tripyrrolemethane Group: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidtchen, F.P. Surprises in the energetics of host–guest anion binding to Calix [4] pyrrole. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, F.M.; Seter, M.; Lewcenko, N.; Barnett, N.W. Fluorescent anion sensors based on 4-amino-1, 8-naphthalimide that employ the 4-amino N–H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 5241–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cametti, M.; Rissanen, K. Recognition and sensing of fluoride anion. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2809–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custecean, R.; Delmau, L.H.; Moyer, B.A.; Sessler, J.L.; Cho, W.S.; Gross, D.; Bates, G.W.; Brooks, S.J.; Light, M.E.; Gale, P.A. Calix [4] pyrrole: An Old yet New Ion-Pair Receptor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2537–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, D.; Cowley, A.; Beer, P.D.; Curiel, D.; Cowley, A.; Beer, P.D. Indolocarbazoles: A new family of anion sensors. Chem. Commun. 2005, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, L.; León, A.; Olives, A.I.; del Castillo, B.; Martin, M.A. Spectrofluorimetric determination of stoichiometry and association constants of the complexes of harmane and harmine with beta-cyclodextrin and chemically modified beta-cyclodextrins. Talanta 2003, 60, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Paul, A.K.; Stoeckli-Evans, H. A family of highly selective fluorescent sensors for fluoride based on excited state proton transfer mechanism. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 202, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Bai, Y.; Ma, L.; Yan, X.-P. Synthesis and characterization of indolocarbazole-quinoxalines with flat rigid structure for sensing fluoride and acetate anions. Org. Biomol Chem. 2008, 6, 1751–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxami, V.; Kumar, S. Colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescence sensing of fluoride ions based on competitive intra-and intermolecular proton transfer. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 3083–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, T.; Sivaraman, G.; Iniya, M.; Siva, A.; Chellappa, D. Aminobenzohydrazide based colorimetric and “turn-on” fluorescence chemosensor for selective recognition of fluoride. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 876, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, J.; Hamase, K.; Zaitsu, K. Evaluation of a simple and novel fluorescent anion sensor, 4-quinolone, and modification of the emission color by substitutions based on molecular orbital calculations. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 10065–10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-S.; Ahn, K.H. Fluorescence “turn-on” sensing of carboxylate anions with oligothiophene-based o-(carboxamido) trifluoroacetophenones. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6831–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, C.; Bates, G.W.; Gale, P.H.; Light, M.E. Anion binding vs. sulfonamide deprotonation in functionalised ureas. Chem. Commun. 2008, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michał, J.; Chmielewski, M.J.; Charon, M.; Jurczak, J. 1,8-Diamino-3,6-dichlorocarbazole: A Promising Building Block for Anion Receptors. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3501–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Janosik, T.; Wahlström, N.; Bergman, J. Recent progress in the chemistry and applications of indolocarbazoles. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 9159–9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortino, S.; Conoci, S. Selective binding of 2-anthrylmethylpyrrole with fluoride: Fluorescence and theoretical studies. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 323, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | λex (nm) | λem (nm) | FI 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 297 | 352 | 0.22 |

| 2a | 256, 292 | 338 | 10.0 |

| 2b | 258, 290, 324, 336 | 364 | 62.5 |

| 2c | 252, 290 | 368 | 71.0 |

| 2d | 256, 302 | 348 | 42.6 |

| 2e | 256, 302 | 350 | 100 |

| 3 | 294 | 326 | 0.04 |

| Complex | Free Energy (kJ mol−1) | Difference to Acetone (kJ mol−1) | Ligand-NH Distance (Å) | Ligand-OH Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2c-acetone | −79.48 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 1.83 |

| 2c-F− | −484.67 | 405.19 | 1.54 | 1.21 |

| 2c-CN− | −213.29 | 133.81 | 1.93 | 1.65 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Ruiz, V.; Cores, Á.; Caja, M.M.; Sridharan, V.; Villacampa, M.; Martín, M.A.; Olives, A.I.; Menéndez, J.C. Fluorescence Sensors Based on Hydroxycarbazole for the Determination of Neurodegeneration-Related Halide Anions. Biosensors 2022, 12, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12030175

González-Ruiz V, Cores Á, Caja MM, Sridharan V, Villacampa M, Martín MA, Olives AI, Menéndez JC. Fluorescence Sensors Based on Hydroxycarbazole for the Determination of Neurodegeneration-Related Halide Anions. Biosensors. 2022; 12(3):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12030175

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Ruiz, Víctor, Ángel Cores, M. Mar Caja, Vellaisamy Sridharan, Mercedes Villacampa, M. Antonia Martín, Ana I. Olives, and J. Carlos Menéndez. 2022. "Fluorescence Sensors Based on Hydroxycarbazole for the Determination of Neurodegeneration-Related Halide Anions" Biosensors 12, no. 3: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12030175