Traditional Italian Agri-Food Products: A Unique Tool with Untapped Potential

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

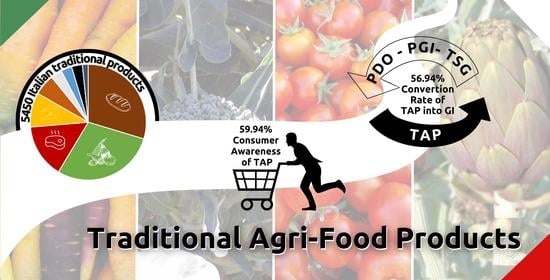

3.1. TAP Recognition: The Literature Research Results

3.2. TAP in Italy: Bureaucratic Procedures and Figures

3.3. Consumer Knowledge and Awareness of TAPs

3.4. TAP and European Quality Regimes: An Analysis and Comparison

- ‘Protected Designation of Origin’ (PDO): A name that identifies a product: (a) originating in a specific place, region, or in exceptional cases, a country; (b) whose quality or characteristics are essentially or exclusively due to a particular geographical environment with its inherent natural and human factors; and (c) the production steps of which all take place in the defined geographical area;

- ‘Protected Geographical Indication’ (PGI): A name that identifies a product: (a) originating in a specific place, region or country; (b) whose given quality, reputation or other characteristic is essentially attributable to its geographical origin; and (c) at least one of the production steps of which takes place in the defined geographical area;

- ‘Traditional Specialty Guaranteed’ (TSG): A name that describes a specific product or foodstuff (a) that results from a mode of production, processing or composition corresponding to traditional practices for that product or foodstuff or (b) is produced from raw materials or ingredients that are traditionally used (article 18, paragraph 1). Furthermore, for a name to be registered as a traditional specialty guaranteed, it shall: (a) have been traditionally used to refer to the specific product; or (b) identify the traditional character or specific character of the product (article 18, paragraph 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. TAP Denomination for Protection and Valorisation of Traditional Agri-Food Products: SWOT Analysis

4.2. A Focus on the Protection and Valorisation of Traditional Agri-Food Vegetable Products

4.3. Italian Traditional Agri-Food Products: Future Evolutions of TAP Recognition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristics | TAP | PDO | PGI | TSG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditionality and connection to the territory (years) * | Yes (25 years) | Yes (25 years—also non-continuous) | Yes (25 years—also non-continuous) | Yes (30 years) |

| Guaranteed local origin | No | Yes (all stages of production) | Yes (at least one production stage) | No |

| Subject entitled to register | Autonomous region or province, public and private entities | Association consisting mainly of producers or processors involved in production (c.d. «group») | Association consisting mainly of producers or processors involved in production (c.d. «group») | Association consisting mainly of producers or processors involved in production (c.d. «group») |

| Requirements for registration * | (a) Name of the product and any other names (b) Brief description of the product (c) Area of origin of the product and territory concerned (d) Nutritional aspects (e) Description of the processing, storage and maturing methods (f) Materials, specific equipment used for preparation and conditioning (g) Description of the processing, storage and maturing rooms (h) Evidence that the methods have been applied uniformly and according to traditional rules for a period of not less than 25 years (i) Production holdings (j) Promotion initiatives | (a) Constitutive act and/or articles of association, resolution of the assembly referring to the application (b) Name to be protected (c) Description of the product, including main physical, chemical, microbiological and organoleptic characteristics (d) Definition of the defined geographical area (e) Evidence that the product originates in the defined geographical area (f) Description of the method of production and, where applicable, local, fair and consistent methods, as well as information on packaging (g) Elements establishing the link between the quality or characteristics of the product and the geographical environment (h) Historical report, accompanied by bibliographical references, proving the production for at least twenty-five years, even if not continuous, of the product, as well as the established use, in trade or in common parlance, of the name for which registration is sought * (i) Socio-economic report containing the quantity produced with reference to the last three years of production and the number of companies involved (current and potential) (j) Cartography on a scale sufficient to permit identification of the production area and its boundaries (k) Name and address of the inspection authority or body (l) Possible specific labelling rules | (a) Constitutive act and/or articles of association, resolution of the assembly referring to the application (b) Name to be protected (c) Description of the product, including main physical, chemical, microbiological and organoleptic characteristics (d) Definition of the defined geographical area (e) Evidence that the product originates in the defined geographical area (f) Description of the method of production and, where applicable, local, fair and consistent methods, as well as information on packaging (g) Elements establishing the link between a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the product and the geographical environment (h) Historical report, accompanied by bibliographical references, proving the production for at least twenty-five years, even if not continuous, of the product, as well as the established use, in trade or in common parlance, of the name for which registration is sought * (i) Socio-economic report containing the quantity produced with reference to the last three years of production and the number of companies involved (current and potential) (j) Cartography on a scale sufficient to permit identification of the production area and its boundaries (k) Name and address of the inspection authority or body (l) Possible specific labelling rules | (a) Constitutive act and/or articles of association, resolution of the assembly referring to the application (b) Name to be protected (c) Description of the product, including the main physical, chemical, microbiological and organoleptic characteristics and demonstration of the product’s specificity (d) Description of the production method to be followed by the producers comply with, including, where applicable, the nature and characteristics of the raw materials or ingredients used and the method of production of the product (e) Key elements attesting to the traditional character of the product (f) Historical report, accompanied by bibliographical references, proving that the product is obtained by a method of production, processing or composition corresponding to traditional practice for that product or foodstuff or obtained from raw materials or ingredients used traditionally, as well as the use established in the trade or in common parlance of the name for which registration is sought (g) Socio-economic report containing the quantity produced with reference to the last three years of production and the number of companies involved (current and potential) (h) Possible specific labelling rules |

| Product Specification | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Protection of the registered name | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Monitoring organisation | Absent | Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies—Department of the Central Inspectorate for the protection of quality and repression of frauds of agri-food products; monitoring organisations authorised according to article 14, paragraph 6, L.526/99; protection consortium according to article 14, paragraph 15, L.526/99, in compliance with article 34–40, Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012. | Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies—Department of the Central Inspectorate for the protection of quality and repression of frauds of agri-food products; monitoring organisations authorised according to article 14, paragraph 6, L.526/99; protection consortium according to article 14, paragraph 15, L.526/99, in compliance with article 34–40, Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012. | Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies—Department of the Central Inspectorate for the protection of quality and repression of frauds of agri-food products; monitoring organisations authorised according to article 14, paragraph 6, L.526/99; protection consortium according to article 14, paragraph 15, L.526/99, in compliance with article 34–40, Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012. |

| Labelling indications | No trademark. Is possible to insert in the label the indication ‘Product on the List of Traditional Agri-Food Products’. | Name of the product; indication of protection (PDO); EU PDO protection symbol; control information; logo of the product or of the Protection Consortium (where present), ex-article 12, Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 and article 13, Regulation (EU) n. 668/2014. | Name of the product; indication of protection (PGI); EU PGI protection symbol; control information; logo of the product or of the Protection Consortium (where present), ex-article, 12 Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 and article 13, Regulation (EU) n. 668/2014. | Name of the product; indication of protection (TSG); EU TSG protection symbol; control information; logo of the product or of the Protection Consortium (where present), ex-article 12, Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 and article 13, Regulation (EU) n. 668/2014. |

| Number of registered products (Italy) | 5450 | 173 | 142 | 4 |

| Number of registered vegetable products (Italy) | 911 | 19 | 37 | 0 |

| Average time for registration in days (Italy) | 365 ** | 1107 | 621 | N.R. *** |

References

- Renna, M.; Signore, A.; Santamaria, P. I Prodotti Agroalimentari Tradizionali (PAT), Espressione Del Territorio e Del Patrimonio Culturale Italiano. Italus Hortus 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalkos, D.; Kosma, I.S.; Chasioti, E.; Skendi, A.; Papageorgiou, M.; Guiné, R.P.F. Consumers’ Attitude and Perception toward Traditional Foods of Northwest Greece during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURISPES. 29° Rapporto Italia. Percorsi di Ricerca Nella Società Italiana; Minerva Edizioni: Bologna, Italy, 2017; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Nemes, G.; Chiffoleau, Y.; Zollet, S.; Collison, M.; Benedek, Z.; Colantuono, F.; Dulsrud, A.; Fiore, M.; Holtkamp, C.; Kim, T.Y.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Alternative and Local Food Systems and the Potential for the Sustainability Transition: Insights from 13 Countries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Cities and Local Governments at the Forefront in Building Inclusive and Resilient Food Systems. In Key Results from the FAO Survey “Urban Food Systems and COVID-19”; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, P.; Ronchi, L. Varietà da conservazione in Italia: Lo stato dell’arte per le specie orticole. Italus Hortus 2016, 23, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalis, S.; Valdramidis, V.P.; Argyropoulos, D.; Ahrne, L.; Chen, J.; Cullen, P.J.; Cummins, E.; Datta, A.K.; Emmanouilidis, C.; Foster, T.; et al. Perspectives from CO+RE: How COVID-19 changed our food systems and food security paradigms. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Sacchi, G.; Carfora, V. Resilience effects in food consumption behaviour at the time of COVID-19: Perspectives from Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany, D.; Canales, E.; Low, S.A.; Boys, K. Local food supply chain dynamics and resilience during COVID-19. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Disruption & Uncertainty—The State of Grocery Retail 2021, Europe; McKinsey & Company: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Case for a Local Farming and Direct Sales Labelling Scheme. Brussels, 13 December 2013, COM (2013), 866 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:be106719-60e5-11e3-ab0f-01aa75ed71a1.0008.01/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Law n. 61 of 17 May 2022. Norms for the Valorisation and Promotion of Agricultural and Food Products at Zero Kilometre and Those From Short Supply Chain (Published in the Official Journal n. 135 of 11 June 2022). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/06/11/22G00070/sg (accessed on 2 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Guerrero, L.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Xicola, J.; Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Sajdakowska, M.; Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Issanchou, S.; Contel, M.; et al. Consumer-driven definition of traditional food products and innovation in traditional foods. A qualitative cross-cultural study. Appetite 2009, 52, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. CORDIS EU Research Results. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/16264 (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Ministerial Decree n. 350 of 8 September 1999. Regulation Containing Rules for the Identification of Traditional Products Pursuant to Article 8, Paragraph 1, of Legislative Decree n. 173 of 30 April 1998 (Published in the Official Journal n. 240 of 12 October 1999). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1999/10/12/099G0423/sg (accessed on 2 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Legislative Decree n. 173 of 30 April 1998. Provisions on the Containment of Production Costs and the Structural Strengthening of Agricultural Enterprises, Pursuant to Article 55, Paragraphs 14 and 15, of Law n. 449 of 27 December 1997 (Published in Official Journal n. 129 of 5 June 1998). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1998-06-05&atto.codiceRedazionale=098G0223&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 2 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Bentivoglio, D.; Bucci, G.; Finco, A. Farmers’ general image and attitudes to traditional mountain food labelled: A SWOT analysis. Qual.-Access Success 2019, 20, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rocillo-Aquino, Z.; Cervantes-Escoto, F.; Leos-Rodríguez, J.A.; Cruz-Delgado, D.; Espinoza-Ortega, A. What is a traditional food? Conceptual evolution from four dimensions. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union, L 343, Volume 55, 14 December 2012. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32012R1151 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Marino, M.; Bianchi, P.; Bocci, R.; Bravi, R.; Ragione, I.; Di Matteo, A.; Fideghelli, C.; Fontana, M.; Macchia, M.; Maggioni, L.; et al. Linee Guida per la Conservazione e la Caratterizzazione Della Biodiversità Vegetale di Interesse per L’agricoltura; INEA—Istituto Nazionale di Economia Agraria: Roma, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Celano, G.; Costantino, G.; Calasso, M.; Randazzo, C.; Minervini, F. Distinctive Traits of Four Apulian Traditional Agri-Food Product (TAP) Cheeses Manufactured at the Same Dairy Plant. Foods 2022, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerial Decree 25 February 2022. Update of the National List of Traditional Agri-Food Products Pursuant to Article 12(1) of Law n. 238 of 12 December 2016 (Published in Official Journal n. 67 of 21 March 2022, Ordinary Supplement n. 12). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2022/03/21/67/so/12/sg/pdf (accessed on 13 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Ministerial Circular n. 10 of 21 December 1999. Criteria and Modalities for the Preparation of the Lists of the Regions and Autonomous Provinces of traditional Food Products-Ministerial Decree n. 350 of 8 September 1999. Available online: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/sites/default/files/media/documenti/2018-11/circ_10.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Ministerial Decree 18 July 2000. National List of Traditional Agri-Food Products (Published in Official Journal n. 194 of 21 August 2000). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2000-08-21&atto.codiceRedazionale=00A10395&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 2 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Mania, M.; Nedumaran, G. Consumer perception and SWOT analysis of organic food products. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual International Research Conference, Faculty of Management and Commerce of South Eastern University, Sri Lanka, South Asia, 25 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chalupová, M.; Rojík, S.; Kotoučková, H.; Kauerová, L. Food labels (quality, origin, and sustainability): The experience of Czech producers. Sustainability 2020, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoli, D.; Sanvictores, T.; An, J. SWOT Analysis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cafiero, C.; Palladino, M.; Marcianò, C.; Romeo, G. Traditional agri-food products as a leverage to motivate tourists: A meta-analysis of tourism-information websites. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2019, 13, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerial Circular of 3 July 2000. Publication of the List of Traditional Products. Prot. no 62359. Available online: https://www.regione.puglia.it/documents/2096627/0/Circolare+del+3+luglio+2000.pdf/81172d38-81a7-3153-95a4-a12af200e593?t=1652868749778 (accessed on 9 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Ministerial Decree of 9 April 2008. Identification of Italian Agri-Food Products as An Expression of Italian Cultural Heritage (Published in the Official Journal n. 93 of 19 April 2008). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2008-04-19&atto.codiceRedazionale=08A02593 (accessed on 8 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Sampalean, N.I.; Rama, D.; Visentin, G. An investigation into Italian consumers’ awareness, perception, knowledge of European Union quality certifications, and consumption of agri-food products carrying those certifications. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2021, 10, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee of the Regions. Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on ‘Promoting and Protecting Local Products—A Trump-Card for the Regions. Official Journal of the European Communities, C 34, Volume 40, 3 February 1997. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:51996IR0054 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- ouncil Regulation (EEC) n. 2081/92 of 14 July 1992 on the Protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Communities, L 208, Volume 35. 24 July 1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:31992R2081 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Council Regulation (EEC) No 2082/92 of 14 July 1992 on Certificates of Specific Character for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Communities, L 208, Volume 35. 24 July 1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:31992R2082 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) n. 664/2014 of 18 December 2013 supplementing Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to the Establishment of the Union Symbols for Protected Designations of Origin, Protected Geographical Indications and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed and with Regard to Certain Rules on Sourcing, Certain Procedural Rules and Certain Additional Transitional Rules. Official Journal of the European Union, L 179, Volume 57, 19 June 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32014R0664 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 665/2014 of 11 March 2014 Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to Conditions of Use of the Optional Quality Term ‘Mountain Product’. Official Journal of the European Union, L 179, Volume 57, 19 June 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32014R0665 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) n. 668/2014 of 13 June 2014 Laying Down Rules for the Application of Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union, L 179, Volume 57, 19 June 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32014R0668 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Ministerial Decree 14 October 2013. Decree Laying Down National Provisions for the Implementation of Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs as Regards PDOs, PGIs and TSGs (published in Official Journal n. 251 of 25 October 2013). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2013/10/25/13A08515/sg (accessed on 2 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies. Ministerial Note 27 November 2007. prot. 22514.

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document Evaluation of Geographical Indications and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed Protected in the EU. Brussels, 20 December 2021, SWD (2021), 427 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=SWD:2021:427:FIN&from=EN (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- CREA. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/-/crea-l-agro-alimentare-italiano-settore-chiave-dell-economia-leader-in-europa-per-valore-aggiunto-agricolo-1 (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Fortis, M.; Sartori, A.; Corradini, S.; Carminati, M. Il Settore Agroalimentare Italiano; Fondazione Edison—Fondazione Argentina Altobelli: Bologna, Itaily, 2022; p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Cialfa, E.; Leclercq, C.; Toti, E. The Mediterranean Diet revisited. Focus on fruit and vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 1994, 45, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, E.; Carocho, M.; Di Gioia, F.; Petropoulos, S.A. The beneficial health effects of vegetables and wild edible greens: The case of the Mediterranean Diet and its sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, A.; Santamaria, P. Biodiversity in vegetable crops, a heritage to save: The case of Puglia Region. Ital. J. Agron. 2013, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on European Union Geographical Indications for Wine, Spirit Drinks and Agricultural Products, and Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products, amending Regulations (EU) n. 1308/2013, (EU) n. 2017/1001 and (EU) n. 2019/787 and Repealing Regulation (EU) n. 1151/2012. Brussels, 31 March 2022, COM (2022), 134 final, 2022/0089 (COD). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022PC0134 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Apulia Region. Regional Law 11 December 2013, n. 39. Protection of Native Genetic Resources of Agricultural, Forestry and Zootechnical Interest (Published in Official Bulletin of the Apulia Region n. 166 of 17 December 2013). Available online: https://biodiversitapuglia.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/B.U.R.P.-n.166-del-17122013.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Cilardi, A.M.; Trotta, L.; Santamaria, P. Registro Regionale delle Risorse Genetiche Autoctone; Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro: Bari, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-88-6629-033-9. [Google Scholar]

- Law n. 194 of 1 December 2015. Provisions for the Protection and Enhancement of Biodiversity of Agricultural and Food Interest (Published in Official Journal n. 288 of 11 December 2015). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2015/12/11/15G00210/sg%20 (accessed on 12 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Cefola, M.; Pace, B.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P.; Signore, A.; Serio, F. Compositional analysis and antioxidant profile of yellow, orange and purple Polignano carrots. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2012, 24, 284–291. [Google Scholar]

- Renna, M.; Serio, F.; Signore, A.; Santamaria, P. The yellow–purple Polignano carrot (Daucus Carota L.): A multicoloured landrace from the Puglia region (Southern Italy) at risk of genetic erosion. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2014, 61, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signore, A.; Renna, M.; D’Imperio, M.; Serio, F.; Santamaria, P. Preliminary evidences of biofortification with iodine of “Carota di Polignano”, an Italian carrot landrace. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renna, M.; Durante, M.; Gonnella, M.; Buttaro, D.; D’Imperio, M.; Mita, G.; Serio, F. Quality and nutritional evaluation of Regina Tomato, a traditional long-storage landrace of Puglia (Southern Italy). Agriculture 2018, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renna, M.; D’Imperio, M.; Gonnella, M.; Durante, M.; Parente, A.; Mita, G.; Santamaria, P.; Serio, F. Morphological and chemical profile of three Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) landraces of a semi-arid mediterranean environment. Plants 2019, 8, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Didonna, A.; Colonna, M.A.; Renna, M.; Signore, A.; Santamaria, P. Atlante Dei Prodotti Agroalimentari Tradizionali di Puglia; Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro: Bari, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-88-6629-038-4. [Google Scholar]

- ANSA. Available online: https://www.ansa.it/canale_terraegusto/notizie/ministero_delle_politiche_agricole/2022/09/06/nasce-fondo-tutela-5450-prodotti-agroalimentari-tradizionali_d107ed3d-d2be-43bc-a677-5e10d57c70df.html (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Lazio Region. Regional Council Resolution n. 722 of 13 October 2020. Approval of the Public Announcement: ‘COVID-19-Bonus Lazio km Zero (0)-Measures to Support Catering Activities that Serve Typical and Quality Food Products from the Region’s Territory’ (Published in the Official Bulletin of the Lazio Region n. 127 of 20 October 2020). Available online: https://www.regione.lazio.it/sites/default/files/documentazione/AGC_DD_G09375_13_07_2021.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023). (In Italian).

- Santeramo, F.G.; Manno, R.; Tappi, M.; Lamonaca, E. Trademarks and territorial marketing: Retrospective and prospective analyses of the trademark “Prodotti Di Qualità”. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2022, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencati, A.; Zsolnai, L. Collaborative enterprise and sustainability: The case of Slow Food. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaďuďová, J.; Tomaškin, J.; Ševčíková, J.; Andráš, P.; Drimal, M. The Importance of Environmental Food Quality Labels for Regional Producers: A Slovak Case Study. Foods 2002, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Title | Aim of Study | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renna et al. [1] | 2018 | Traditional Agrifood Products: An Expression of Italian Cultural Heritage | Analysing the numbers and uses of TAP recognition in relation to vegetable landraces. | The article proposes the TAP denomination as a useful leverage for the promotion of “made in Italy”. Calling for the formulation of a model of enhancement, including a simple labelling regime and the creation of a national atlas of TAPs. |

| Cafiero et al. [28] | 2020 | Traditional Agri-Food Products as a Leverage to Motivate Tourists: A Meta-Analysis of Tourism-Information Websites | Provide evidence on the extent to which traditional agri-food products (TAPs) constitute leverage to promote tourism in the province of Reggio Calabria, Italy. | The database on the TFPs of the province of Reggio Calabria permits easy reading of the geographical distribution of the different categories of products, useful as a resource for further studies and as a local development policy support tool. |

| Region | (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 149 | 30 | 17 | 11.41% |

| Aosta Valley | 36 | 2 | 0 | 0.00% |

| Apulia | 329 | 127 | 100 | 30.40% |

| Basilicata | 211 | 81 | 52 | 24.64% |

| Bolzano Aut.Pr. | 102 | 18 | 6 | 5.88% |

| Calabria | 269 | 73 | 37 | 13.75% |

| Campania | 580 | 240 | 126 | 21.72% |

| Emilia-Romagna | 398 | 58 | 19 | 4.77% |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 181 | 49 | 32 | 17.68% |

| Lazio | 456 | 110 | 73 | 16.01% |

| Liguria | 300 | 105 | 45 | 15.00% |

| Lombardy | 268 | 34 | 18 | 6.72% |

| Marche | 154 | 42 | 13 | 8.44% |

| Molise | 159 | 30 | 22 | 13.84% |

| Piedmont | 342 | 94 | 70 | 20.47% |

| Sardinia | 222 | 58 | 23 | 10.36% |

| Sicily | 269 | 81 | 35 | 13.01% |

| Trento Aut.Pr. | 105 | 16 | 11 | 10.48% |

| Tuscany | 464 | 194 | 122 | 26.29% |

| Umbria | 69 | 12 | 11 | 15.94% |

| Veneto | 387 | 123 | 79 | 20.41% |

| Total | 5450 | 1577 | 911 | 16.72% |

| Variable | Levels | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 216 | 68.1% |

| Male | 101 | 31.9% | |

| Age (in years) | <18 | 1 | 0.3% |

| 18–35 | 73 | 23.0% | |

| 35–64 | 217 | 68.5% | |

| >64 | 26 | 8.2% | |

| Education | Primary school qualification | 0 | 0.0% |

| Junior high school qualification | 21 | 6.6% | |

| High school qualification | 116 | 36.6% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 32 | 10.1% | |

| Master’s degree | 105 | 33.1% | |

| Post graduate training/PhD | 43 | 13.6% | |

| Geographical Distribution | North-West | 14 | 4.5% |

| North-East | 39 | 12.4% | |

| Centre | 14 | 4.5% | |

| South | 246 | 77.6% | |

| Islands | 3 | 1.0% | |

| Area of origin | Rural | 43 | 13.6% |

| Urban | 274 | 86.4% | |

| Economic status | Very difficult | 25 | 7.9% |

| Difficult | 22 | 6.9% | |

| Stable | 175 | 55.2% | |

| Satisfactory | 80 | 25.2% | |

| Very satisfactory | 15 | 4.7% | |

| Occupation | Employee (public or private) | 155 | 48.9% |

| Entrepreneur | 14 | 4.4% | |

| Freelance | 39 | 12.3% | |

| Housewife | 15 | 4.8% | |

| Retired | 31 | 9.8% | |

| Student | 23 | 7.3% | |

| Unemployed | 23 | 7.3% | |

| Others | 17 | 5.2% |

| Parameter | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Historical and cultural link with the territory of origin | 2.76 | 1.11 |

| Nutritional aspects | 3.28 | 1.09 |

| Organic product | 2.48 | 1.06 |

| Price | 2.65 | 0.78 |

| Product of certified origin (PDO, PGI, etc.) | 2.57 | 1.08 |

| Regional origin of the product | 3.14 | 1.08 |

| Seasonality | 3.59 | 1.04 |

| Parameter | (LVP) | (SD) | (TVP) | (SD) | (S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthier product | 3.17 | 1.00 | 3.14 | 0.98 | |

| Higher-quality product | 3.18 | 0.95 | 3.07 | 0.92 | * |

| Higher level of food safety | 2.99 | 0.98 | 2.97 | 0.93 | |

| Improved nutritional values | 3.06 | 1.04 | 3.05 | 0.99 | |

| Increased respect for local farmers’ rights | 3.17 | 1.02 | 2.99 | 1.05 | *** |

| More expensive product | 2.64 | 1.04 | 2.67 | 1.01 | |

| More sustainable product | 3.46 | 0.99 | 3.18 | 1.04 | *** |

| Class of Product | (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit, vegetables and cereals fresh or processed | 120 | 96 | 65 | 52.85% | 67.71% | 30.09% |

| Cheeses | 56 | 25 | 18 | 14.63% | 72.00% | 8.33% |

| Meat products (cooked, salted, smoked, etc.) | 43 | 19 | 13 | 10.57% | 68.42% | 6.02% |

| Bread, pastry, cakes, confectionery, etc. | 16 | 15 | 9 | 7.32% | 60.00% | 4.17% |

| Fresh fish, mollusks and crustaceans | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4.07% | 83.33% | 2.31% |

| Pasta | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3.25% | 80.00% | 1.85% |

| Oils and fats (butter, margarine, oil, etc.) | 49 | 28 | 3 | 2.44% | 10.71% | 1.39% |

| Other products of Annex I of the Treaty | 7 | 7 | 2 | 1.63% | 28.57% | 0.93% |

| Other products of animal origin | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0.81% | 20.00% | 0.46% |

| Fresh meat (and offal) | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0.81% | 20.00% | 0.46% |

| Chocolate and derived products | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.81% | 100.00% | 0.46% |

| Aromatised wines | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | n.c. | 0.00% |

| Prepared dishes | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.81% | 50.00% | 0.46% |

| Essential oils | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Salt | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Total | 319 | 216 | 123 | 100% | 56.94% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Didonna, A.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P. Traditional Italian Agri-Food Products: A Unique Tool with Untapped Potential. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071313

Didonna A, Renna M, Santamaria P. Traditional Italian Agri-Food Products: A Unique Tool with Untapped Potential. Agriculture. 2023; 13(7):1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071313

Chicago/Turabian StyleDidonna, Adriano, Massimiliano Renna, and Pietro Santamaria. 2023. "Traditional Italian Agri-Food Products: A Unique Tool with Untapped Potential" Agriculture 13, no. 7: 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071313