Traumatised Children’s Perspectives on Their Lived Experience: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection Procedures

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Qualitative Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

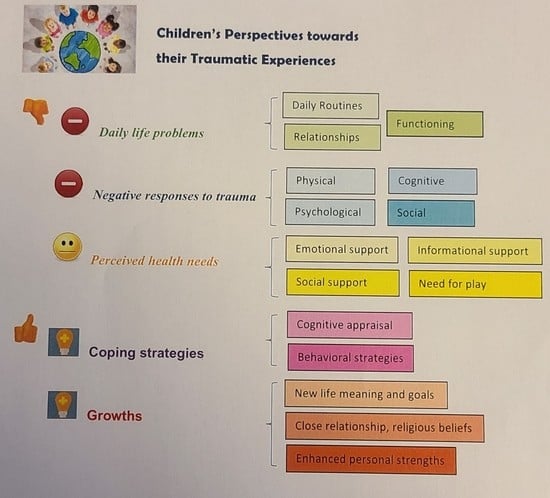

3.3. Main Findings of Qualitative Studies

3.3.1. Daily Life Problems Related to Trauma

3.3.2. Negative Responses to Trauma

Physical Aspect

Psychological Aspect

Cognitive Aspect

Behavioural Aspect

Social Aspect

3.3.3. Perceived Health Needs

3.3.4. Coping Strategies Related to Trauma and Stress

Cognitive Coping Strategies

Behavioural Coping Strategies

3.3.5. Growth from Traumatic Experience

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Pub.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alisic, E.; Jongmans, M.J.; van Wesel, F.; Kleber, R.J. Building Child Trauma Theory from Longitudinal Studies: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.J.; Arseneault, L.; Caspi, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Matthews, T.; Moffitt, T.E.; Odgers, C.L.; Stahl, D.; Teng, J.Y.; Danese, A. The Epidemiology of Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in a Representative Cohort of Young People in England and Wales. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Koenen, K.C.; Hill, E.D.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a National Sample of Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 815–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakeyar, C.; Esses, V.; Reid, G.J. The Psychosocial Needs of Refugee Children and Youth and Best Practices for Filling These Needs: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, S.M.; Bilsky, S.A.; Dutton, C.; Badour, C.L.; Feldner, M.T.; Leen-Feldner, E.W. Lifetime Histories of PTSD, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts in a Nationally Representative Sample of Adolescents: Examining Indirect Effects via the Roles of Family and Peer Social Support. J. Anxiety Disord. 2017, 49, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, K.J.; Denietolis, B.; Goodwin, B.J.; Dvir, Y. Childhood Trauma and Psychosis: An Updated Review. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 29, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.A.; Fairbank, D.W. Epidemiology of Child Traumatic Stress. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.M.; Campbell, K.; Shanley, P.; Crusto, C.A.; Connell, C.M. Building Capacity for Trauma-Informed Care in the Child Welfare System: Initial Results of a Statewide Implementation. Child Maltreat. 2016, 21, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, E.; Adamson, G.; Rosato, M.; De Cock, P.; Leavey, G. Profiles of Childhood Trauma and Psychopathology: US National Epidemiologic Survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, L.; Knutsson, S.; Huus, K.; Enskar, K. The Everyday Life of the Young Child Shortly After Receiving a Cancer Diagnosis, From Both Children’s and Parent’s Perspectives. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnie, A.G. Emerging Themes in Coping with Lifetime Stress and Implication for Stress Management Education. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118782545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wesel, F.; Boeije, H.; Alisic, E.; Drost, S. I’ll Be Working My Way Back: A Qualitative Synthesis on the Trauma Experience of Children. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2012, 4, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Asgari, Z.; Naghavi, A. The Experience of Adolescents’ Post-Traumatic Growth after Sudden Loss of Father. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M.; Kohli, A.; Remy, M.M.; Murhula, C.M.; Kurhorhwa, A.K.B.; Mirindi, A.B.; Bufole, N.M.; Banywesize, J.H.; Ntakwinja, G.M.; Kindja, G.M.; et al. Coping among Trauma-Affected Youth: A Qualitative Study. Confl. Health 2015, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, J.; Joscelyne, T. “I Thought It Was Normal”: Adolescents’ Attempts to Make Sense of Their Experiences of Domestic Violence in Their Families. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 5250–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egberts, M.R.; Geenen, R.; de Jong, A.E.; Hofland, H.W.; Van Loey, N.E. The Aftermath of Burn Injury from the Child’s Perspective: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 2464–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, C.J.; Martinez-Torteya, C.; Taing, S.; Chhim, S.; Hinton, D.E. Key Expressions of Trauma-Related Distress in Cambodian Children: A Step toward Culturally Sensitive Trauma Assessment and Intervention. Transcult. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.M. It Happened to Me: A Qualitative Analysis of Boys’ Narratives About Child Sexual Abuse. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2017, 26, 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.M.; Hagedorn, W.B. Through the Eyes of the Wounded: A Narrative Analysis of Children’s Sexual Abuse Experiences and Recovery Process. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2014, 23, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazneh, L.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Ayed, A. Resiliency Process and Socialization among Palestinian Children Exposed to Traumatic Experience: Grounded Theory Approach. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 34, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.K.; Ellestad, A.; Dyb, G. Children and Adolescents’ Self-Reported Coping Strategies during the Southeast Asian Tsunami. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 52, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Tyson, S.; Yorke, J.; Davis, N. The Impact of Injury: The Experiences of Children and Families after a Child’s Traumatic Injury. Clin. Rehabil. 2021, 35, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer-Kristensen, R.; Johansen, K.L.G. Hidden Loss: A Qualitative Explorative Study of Children Living with a Parent with Acquired Brain Injury. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Nguyen, A.J.; Russell, T.; Aules, Y.; Bolton, P. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems among Conflict-Affected Children in Kachin State, Myanmar: A Qualitative Study. Confl. Health 2018, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovato, K. Forced Separations: A Qualitative Examination of How Latino/a Adolescents Cope with Parental Deportation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 98, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, S.; Elliott, C.; McDonald, A.; Valentine, J.; Wood, F.; Girdler, S. Paediatric Burns: From the Voice of the Child. Burns 2014, 40, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.; Botha, J.; Spies, R. Voices of Middle Childhood Children Who Lost a Mother. Mortality 2021, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, P.; Lambie, J.; Hale, E. A Qualitative Study of the Emotional Coping and Support Needs of Children Living with a Parent with a Brain Injury. Brain Inj. 2017, 31, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salawali, S.H.; Susanti, H.; Daulima, N.H.C.; Putri, A.F. Posttraumatic Growth in Adolescent Survivors of Earthquake, Tsunami, and Liquefaction in Palu Indonesia: A Phenomenological Study. Pediatr. Rep. 2020, 12, 8699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyerman, E.; Eccles, F.J.R.; Gray, V.; Murray, C.D. Siblings’ Experiences of Their Relationship with a Brother or Sister with a Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 2940–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C.; Hill, J.; Knott, T.; Sault, B. Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Trauma in New Recruits and Experienced Firefighters. Stress Health 2003, 19, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheeringa, M.S.; Zeanah, C.H. A Relational Perspective on PTSD in Early Childhood. J. Trauma. Stress 2001, 14, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Fu, F.; Wu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Y. Longitudinal Relationships Between Neuroticism, Avoidant Coping, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Adolescents Following the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake in China. J. Loss Trauma 2013, 18, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, A.A.; Villalta, I.K.; Ortiz, C.D.; Gottschall, A.C.; Costa, N.M.; Weems, C.F. Social Support, Discrimination, and Coping as Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Reactions in Youth Survivors of Hurricane Katrina. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2008, 37, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.D.; Littleton, H.L.; Grills, A.E. Can People Benefit From Acute Stress? Social Support, Psychological Improvement, and Resilience After the Virginia Tech Campus Shootings. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 4, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Ein-Dor, T.; Solomon, Z. Posttraumatic Growth and Posttraumatic Distress: A Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2012, 4, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamblin, S.; Graham, D.; Bianco, J.A. Creating Trauma-Informed Schools for Rural Appalachia: The Partnerships Program for Enhancing Resiliency, Confidence and Workforce Development in Early Childhood Education. School Ment. Health 2016, 8, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, S.; Sandelowski, M. Focus on Qualitative Methods: Interviewing Children. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsson, S.; Samuelsson, I.P.; Hellström, A.-L.; Bergbom, I. Children’s Experiences of Visiting a Seriously Ill/Injured Relative on an Adult Intensive Care Unit. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 61, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, L.G.; Johnson, J. Interviewing Young Children: Explicating Our Practices and Dilemmas. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, A.C.; Kenardy, J.A.; Cobham, V.E. Trauma in Early Childhood: A Neglected Population. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutrovátz, K. Conducting Qualitative Interviews with Children—Methodological and Ethical Challenges. Corvinus J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2017, 8, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I. Consultation with Children in Hospital: Children, Parents’ and Nurses’ Perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenwald, M.; Baird, J. An Integrated Trauma-Informed, Mutual Aid Model of Group Work. Soc. Work Groups 2020, 43, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Authors, Year of Publication and Country) | Type of Trauma | Sample | Study Design | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asgari and Naghavi (2020) [15], Iran | Sudden loss of a parent | 14 children (age: 14–17) | Qualitative | In-depth and semi-structured interviews |

| Cherewick et al. (2015) [16], Democratic Republic of Congo | Violence | 30 children (age: 10–15) | Qualitative | In-depth interviews (Interview questions given, face-to-face) |

| Chester and Joscelyne (2021) [17], United Kingdom | Domestic violence | 5 children (age: 14–18) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews |

| Darcy et al. (2014) [11], Sweden | Cancer | 13 children (age: 1–6) 23 parents | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Face-to-face, parental presence) |

| Egberts et al. (2020) [18], The Netherlands | Burn injury | 8 children (age: 12–17) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Face-to-face, individual or with parental presence) |

| Figge et al. (2020) [19], Cambodia | Traumatic experiences (e.g., domestic violence) | 30 children (age: 10–13) 30 caregivers | Qualitative | In-person interviews (interview questions given) |

| Foster (2017) [20], United States | Sexual abuse | 19 children (age: 3–17) | Qualitative | Written narratives |

| Foster and Hagedorn (2014) [21], United States | Sexual abuse | 21 children (age: 6–17) | Qualitative | Written narratives |

| Harazneh et al. (2021) [22], Palestine | Political detention | 18 children (age: 12–18) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Face-to-face, individual or parental presence) |

| Jensen et al. (2013) [23], Norway | Tsunami | 56 children (age: 6–18) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (individual, face-to-face) |

| Jones et al. (2021) [24], United Kingdom | Traumatic injury | 13 children (age: 5–15) 19 parents/guardian | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews via telephone call or in-person (Joint or separate with parents/guardian) |

| Kieffer-Kristensen and Johansen (2013) [25], Denmark | Parental ABI | 14 children (age: 7–14) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Face-to-face) |

| Lee et al. (2018) [26], Myanmar | Traumatic experiences (e.g., conflict and violence) | 28 children (age: 12–17) 12 adults (parents/teachers/service providers) | Qualitative | In-depth interviews |

| Lovato (2019) [27], United States | Forced family separation (parental deportation) | 8 children (age: 14–18) 8 mothers 11 school-based staff | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Face-to-face) |

| McGarry et al. (2014) [28], Australia | Burn injury | 12 children (age: 8–15) | Qualitative | In-depth and unstructured interviews (Face-to-face, individual), record all non-verbal cues |

| Parsons et al. (2021) [29], South Africa | Loss of a parent | 22 children (age: 10–12) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Individual) |

| Rohleder et al. (2017) [30], United Kingdom | Parental ABI | 6 children (age: 9–18) 6 parents (3 with ABI) 3 support workers | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Face-to-face) |

| Salawali et al. (2020) [31], Indonesia | Natural disasters | 16 children (age: 12–18) | Qualitative | In-depth interviews (face-to-face, using field notes) |

| Tyerman et al. (2019) [32], United Kingdom | The potential loss of the injured sibling with ABI | 5 children (age: 9–12) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (Individual or with parental presence) |

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Daily life problems related to trauma | Daily routines [11,15,18,19,24,26,27,28,30] |

| Relationship issues [19,21,24,25,26,28,30] | |

| Daily function [15,16,17,18,20,21,24,25,27,28,32] | |

| Negative responses to trauma | Physical aspect [11,15,17,18,19,21,26,27,28,29] |

| Psychological aspect [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] | |

| Cognitive aspect [16,17,18,19,20,21,24,25,27,28,29] | |

| Behavioural aspect [11,15,16,17,18,19,23,24,25,28,29] | |

| Social aspect [15,17,19,21,24,26,29] | |

| Perceived health needs | Emotional support [11,17,18,24,30,32] |

| Social support [16,25,30] | |

| More detailed information [25,30] | |

| Need for play [11,23,24,25] | |

| Coping strategies related to trauma and stress | Cognitive coping strategies [15,16,17,18,23,25,26,28,29,30,31,32] |

| Behavioural coping strategies [15,16,17,18,20,22,23,25,26,28,29,30,32] | |

| Growth from traumatic experience | Meaning of life [15,17,24,28,29,31] |

| Close relationship [17,25,31] | |

| New life goals [15,18,24,28,31] | |

| Personal strengths [15,22,24,28,31] | |

| Religious beliefs [15,16,23,31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chien, W.T.; Lau, C.T. Traumatised Children’s Perspectives on Their Lived Experience: A Review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020170

Chien WT, Lau CT. Traumatised Children’s Perspectives on Their Lived Experience: A Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(2):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020170

Chicago/Turabian StyleChien, Wai Tong, and Chi Tung Lau. 2023. "Traumatised Children’s Perspectives on Their Lived Experience: A Review" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 2: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020170