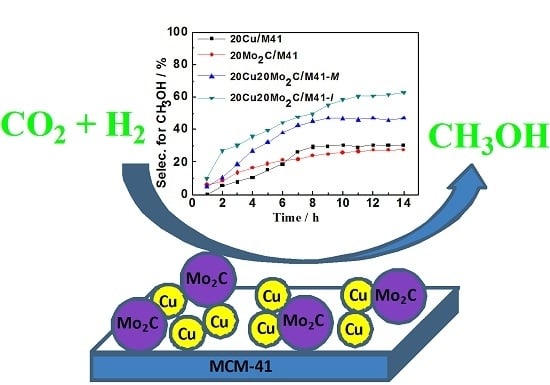

Cu-Mo2C/MCM-41: An Efficient Catalyst for the Selective Synthesis of Methanol from CO2

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalyst Characterization

2.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.1.2. N2 Adsorption–Desorption

2.1.3. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.2. Catalytic Performance for the Hydrogenation of CO2

2.2.1. Catalytic Performance of the yMo2C/M41 Samples

2.2.2. Catalytic Performance for the Cu-Promoted 20Mo2C/M41 Catalyst

2.2.3. The Stability of the 20Cu20Mo2C/M41-I Catalyst

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

3.2. Characterization

3.3. Catalytic Test

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Angelini, A. Catalysis for the valorization of exhaust carbon: From CO2 to chemicals, materials, and fuels. Technological use of CO2. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.L.; Jiang, Z.; Su, D.S.; Wang, J.Q. Research progress on the indirect hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, I. Conversion of carbon dioxide into methanol-a potential liquid fuel: Fundamental challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 221–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Himeda, Y.; Muckerman, J.T.; Manbeck, G.F.; Fujita, E. CO2 hydrogenation to formate and methanol as an alternative to photo- and electrochemical CO2 reduction. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12936–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.A.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Mohamed, A.R. Recent development in catalytic technologies for methanol synthesis from renewable sources: A critical review. Renew. Sust. Energy Rew. 2015, 44, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.L.; Xie, J.R.; Liu, Z.M. A novel Pd-decorated carbon nanotubes-promoted Pd-ZnO catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Catal. Lett. 2015, 145, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Li, H.Y.; Lin, G.D.; Zhang, H.B. Pd-decorated CNT-promoted Pd-Ga2O3 catalyst for hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Catal. Lett. 2011, 141, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, N.; Jiang, X.; Kugai, J.; Song, C.S. Effects of mesoporous silica supports and alkaline promoters on activity of Pd catalysts in CO2 hydrogenation for methanol synthesis. Catal. Today 2012, 194, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Koizumi, N.; Guo, X.W.; Song, C.S. Bimetallic Pd-Cu catalysts for selective CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2015, 170–171, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.A. After oil and gas: Methanol economy. Catal. Lett. 2004, 93, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupulety, N.; Driss, H.; Alhamed, Y.A.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Daous, M.A.; Petrov, L. Studies on Au/Cu-Zn-Al catalyst for methanol synthesis from CO2. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2015, 504, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciani, J.; Mudiyanselage, K.; Xu, F.; Baber, A.E.; Evans, J.; Senanayake, S.D.; Stacchiola, D.J.; Liu, P.; Hrbek, J.; Sanz, J.F. Highly active copper-ceria and copper-ceria-titania catalysts for methanol synthesis from CO2. Science 2014, 345, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladera, R.; Pérez-Alonso, F.J.; González-Carballo, J.M.; Ojeda, M.; Rojas, S.; Fierro, J.L.G. Catalytic valorization of CO2 via methanol synthesis with Ga-promoted Cu-ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2013, 142–143, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyir, J.; de la Piscina, P.R.; Homs, N. Ga-promoted copper-based catalysts highly selective for methanol steam reforming to hydrogen; relation with the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy 2015, 40, 11261–11266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xu, C.H.; Zhao, H.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.Y. Methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation over Cu/γ-Al2O3 catalysts modified by ZnO, ZrO2 and MgO. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 28, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, S.D.; Ramírez, P.J.; Waluyo, I.; Kundu, S.; Mudiyanselage, K.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.; Axnanda, S.; Stacchiola, D.J.; Evans, J.; et al. Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol on CeOx/Cu(111) and ZnO/Cu(111) catalysts: Role of the metal-oxide interface and importance of Ce3+ sites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 1778–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.J.; Chen, S.Y.; Fei, X.Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.C. Catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol: Study of synergistic effect on adsorption properties of CO2 and H2 in CuO/ZnO/ZrO2 system. Catalysts 2015, 5, 1846–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Li, F.; Zhan, H.J.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.K.; Wei, W.; Zhong, L.S.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.H. Influence of Zr on the performance of Cu/Zn/Al/Zr catalysts via hydrotalcite-like precursors for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. J. Catal. 2013, 298, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, F.; Mezzatesta, G.; Zafarana, G.; Trunfio, G.; Frusteri, F.; Spadaro, L. Effects of oxide carriers on surface functionality and process performance of the Cu-ZnO system in the synthesis of methanol via CO2 hydrogenation. J. Catal. 2013, 300, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Delgado, J.J.; Mira, C.; Calvino, J.J.; Bernal, S.; Chiavassa, D.L.; Baltanás, M.A.; Bonivardi, A.L. The role of Pd-Ga bimetallic particles in the bifunctional mechanism of selective methanol synthesis via CO2 hydrogenation on a Pd/Ga2O3 catalyst. J. Catal. 2012, 292, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Q.; Liu, X.R.; Xiao, L.F.; Wu, W.; Zhang, J.W.; Song, X.M. Pd-Promoter/MCM-41: A highly effective bifunctional catalyst for conversion of carbon dioxide. Catal. Lett. 2015, 145, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavassa, D.L.; Barrandeguy, J.; Bonivardi, A.L.; Baltanas, M.A. Methanol synthesis from CO2/H2 using Ga2O3-Pd/silica catalysts: Impact of reaction products. Catal. Today 2008, 133–135, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, B.; Ramanathan, S.; Yu, C.C.; Frühberger, B.; Chen, J.G.; Oyama, S.T. Synthesis, characterization, and reactivity studies of supported Mo2C with phosphorus additive. J. Catal. 1998, 176, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.B.; Boudart, M. Platinum-like behavior of tungsten carbide in surface catalysis. Science 1973, 181, 547–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamic, A.F.; Pham, T.L.H.; Potvin, C.; Manoli, J.M.; Mariadassou, G.D. Kinetics of bifunctional isomerization over carbides (Mo, W). J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 2005, 237, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.F.; Guan, G.Q.; Hao, X.G.; Zuo, Z.J.; Huang, W.; Phanthong, P.; Kusakabe, K.; Abudula, A. Highly-efficient steam reforming of methanol over copper modified molybdenum carbide. RSC. Adv. 2014, 4, 44175–44184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, A.J.; Li, X.S.; Zhang, S.H.; Zhu, A.M.; Ma, Y.F. Ni-modified Mo2C catalysts for methane dry reforming. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2012, 431–432, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.M.; Duchstein, L.D.L.; Wagner, J.B.; Jensen, P.A.; Temel, B.; Jensen, A.D. Catalytic conversion of syngas into higher alcohols over carbide catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 4161–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Lin, M.G.; Jiang, D.; Fang, K.G.; Sun, Y.H. Preparation of promoted molybdenum carbides nanowire for CO hydrogenation. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.H.; Shou, H.; Ferrari, D.; Jones, C.W.; Davi, R.J. Influence of cobalt on rubidium-promoted alumina-supported molybdenum carbide catalysts for higher alcohol synthesis from syngas. Top. Catal. 2013, 56, 1740–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.Q.; Ramirez, P.J.; Stacchiola, D.; Rodriguez, J.A. Synthesis of α-MoC1−x and β-MoCy catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation by thermal carburization of Mo-oxide in hydrocarbon and hydrogen mixtures. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Oshikawa, K.; Kurakami, T.; Miyao, T.; Omi, S. Surface properties of carbided molybdena-alumina and its activity for CO2 hydrogenation. J. Catal. 1998, 180, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Pérez, S.; Viñes, F.; Ramirez, J.A.; Vidal, A.B.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Illas, F. The bending machine: CO2 activation and hydrogenation on δ-MoC(001) and β-Mo2C(001) surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 14912–14921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Evans, J.; Feria, L.; Vidal, A.B.; Liu, P.; Nakamura, K.; Illas, F. CO2 hydrogenation on Au/TiC, Cu/TiC, and Ni/TiC catalysts: Production of CO, methanol, and methane. J. Catal. 2013, 307, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.Q.; Ramĭrez, P.J.; Stacchiola, D.; Brito, J.L.; Rodriguez, J.A. The carburization of transition metal molybdates (MxMoO4, M=Cu, Ni or Co) and the generation of highly active metal/carbide catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation. Catal. Lett. 2015, 145, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Pérez, S.; Ramĭrez, P.J.; Gutiérrez, R.A.; Stacchiola, D.J.; Viñes, F.; Liu, P.; Illas, F.; Rodriguez, J.A. The conversion of CO2 to methanol on orthorhombic β-Mo2C and Cu/β-Mo2C catalysts: Mechanism for admetal induced change in the selectivity and activity. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Choi, S.; Thompson, L.T. Low-temperature CO2 hydrogenation to liquid products via a heterogeneous cascade catalytic system. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Hao, H.L.; Zhang, M.H.; Li, W.; Tao, K.Y. Synthesis and characterization of molybdenum carbides using propane as carbon source. J. Solid State Chem. 2006, 179, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; York, A.P.E.; Williams, V.C.; Al-Megren, H.; Hanif, A.; Zhou, X.; Green, M.L.H. Preparation of molybdenum carbides using butane and their catalytic performance. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 3896–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.T.; Kim, W.B.; Rhee, C.H.; Lee, J.S. Effects of transition metal addition on the solid-state transformation of molybdenum trioxide to molybdenum carbides. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Lin, M.G.; Fang, K.G.; Meng, Y.; Sun, Y.H. Preparation of nanostructured molybdenum carbides for CO hydrogenation. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 20948–20954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Pérez, S.; Viñes, F.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Illas, F. Fundamentals of methanol synthesis on metal carbide based catalysts: Activation of CO2 and H2. Top. Catal. 2015, 58, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Liu, P.; Stacchiola, D.J.; Senanayake, S.D.; White, M.G.; Chen, J.G. Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol: Importance of metal-oxide and metal-carbide interfaces in the activation of CO2. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6696–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Average Cu Crystallite Size (nm) 1 |

|---|---|

| 12Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 10.2 |

| 20Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 24.4 |

| 28Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 33.5 |

| Samples | BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|

| M41 | 1083 | 0.945 |

| 10Mo2C/M41 | 413 | 0.280 |

| 20Mo2C/M41 | 282 | 0.235 |

| 30Mo2C/M41 | 248 | 0.203 |

| 40Mo2C/M41 | 221 | 0.156 |

| Samples | Cu Atom Content (mol %) | Mo Atom Content (mol %) |

|---|---|---|

| 12Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 35.7 | 64.3 |

| 20Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 43.8 | 56.2 |

| 28Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 35.2 | 64.8 |

| Samples | Mo 3d5/2 (eV) | (MoIV + Moδ)/Mototal (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoII | MoIV | Moδ | MoVI | ||

| 20Mo2C/M41 | 228.8 | 229.8 | 232.1 | 233.4 | 46.5 |

| 12Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 228.8 | 229.7 | 232.1 | 233.3 | 48.1 |

| 20Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 229.0 | 229.7 | 232.2 | 233.4 | 52.2 |

| 28Cu20Mo2C/M41-I | 228.9 | 229.6 | 232.1 | 233.3 | 49.2 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Geng, W.; Li, H.; Xiao, L.; Wu, W. Cu-Mo2C/MCM-41: An Efficient Catalyst for the Selective Synthesis of Methanol from CO2. Catalysts 2016, 6, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal6050075

Liu X, Song Y, Geng W, Li H, Xiao L, Wu W. Cu-Mo2C/MCM-41: An Efficient Catalyst for the Selective Synthesis of Methanol from CO2. Catalysts. 2016; 6(5):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal6050075

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoran, Yingquan Song, Wenhao Geng, Henan Li, Linfei Xiao, and Wei Wu. 2016. "Cu-Mo2C/MCM-41: An Efficient Catalyst for the Selective Synthesis of Methanol from CO2" Catalysts 6, no. 5: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal6050075