Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Its Impact on Exercise and Sport Performance in Humans: A Recovery or a Performance-Enhancing Molecule?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection of Articles: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Eligibility criteria were specified (no score).

- Subjects were randomly allocated to groups.

- Allocation was concealed.

- The groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators.

- There was blinding of all subjects.

- There was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy.

- There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome.

- Measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups.

- All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least one key outcome was analysed by “intention to treat”.

- The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome.

- The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Dosage and Biodisponibility

4.2. Antioxidant Activity

4.3. Muscular Injury and Inflammatory Process

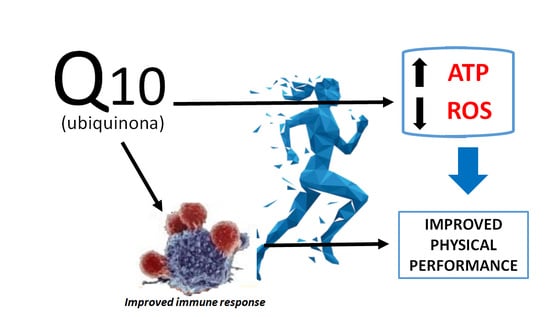

4.4. Sport and Exercise Performance

4.5. Other Action of Coenzyme Q10 Associated to Exercise

5. Recommendations for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamieński, Ł. Shooting Up: A Short History of Drugs and War; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; 381p. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, A.; Rosembloom, P. Mechanisms of skill acquisition and the law of practice. In Cognitive Skills and Their Acquisition; Anderson, J., Ed.; Psychology Press: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 1–55. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/243783833_Mechanisms_of_skill_acquisition_and_the_law_of_practice (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Maughan, R.J.; Burke, L.M.; Dvorak, J.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Peeling, P.; Phillips, S.M.; Rawson, E.S.; Walsh, N.P.; Garthe, I.; Geyer, H.; et al. IOC Consensus Statement: Dietary Supplements and the High-Performance Athlete. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peeling, P.; Binnie, M.J.; Goods, P.S.R.; Sim, M.; Burke, L.M. Evidence-Based Supplements for the Enhancement of Athletic Performance. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dickinson, B.C.; Chang, C.J. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: Introductory Remarks; Oxidative Stress Academic Press: London, UK, 1985; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yavari, A.; Javadi, M.; Mirmiran, P.; Bahadoran, Z. Exercise-induced oxidative stress and dietary antioxidants. Asian J. Sports Med. 2015, 6, 24898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boveris, A.; Chance, B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem. J. 1973, 134, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chance, B.; Williams, G.R. The Respiratory Chain and Oxidative Phosphorylation. In Advances in Enzymology—And Related Areas of Molecular Biology; Nord, F.F., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 65–134. [Google Scholar]

- Brüne, B.; Dehne, N.; Grossmann, N.; Jung, M.; Namgaladze, D.; Schmid, T.; von Knethen, A.; Weigert, A. Redox control of inflammation in macrophages. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 595–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogdan, C.; Röllinghoff, M.; Diefenbach, A. Reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediates in innate and specific immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000, 12, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzano, S.; Checconi, P.; Hanschmann, E.M.; Lillig, C.H.; Bowler, L.D.; Chan, P.; Vaudry, D.; Mengozzi, M.; Coppo, L.; Sacre, S.; et al. Linkage of inflammation and oxidative stress via release of glutathionylated peroxiredoxin-2, which acts as a danger signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12157–12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Lázaro, D.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Seco Calvo, J.; Córdova Martínez, A.; Caballero García, A.; Fernandez-Lazaro, C.I. Modulation of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage, Inflammation, and Oxidative Markers by Curcumin Supplementation in a Physically Active Population: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, A.K.; Mandal, A.; Chanda, D.; Chakraborti, S. Oxidant, antioxidant and physical exercise. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2003, 253, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernster, L.; Dallner, G. Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1271, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhagavan, H.N.; Chopra, R.K. Plasma coenzyme Q10 response to oral ingestion of coenzyme Q10 formulations. Mitochondrion 2007, 7, S78–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.; Davison, G. Targeted Antioxidants in Exercise-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress: Emphasis on DNA Damage. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsmark-Andrée, P.; Ernster, L. Evidence for a protective effect of endogenous ubiquinol against oxidative damage to mitochondrial protein and DNA during lipid peroxidation. Mol. Asp. Med. 1994, 15, s73–s81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lluch, G.; Rodríguez-Aguilera, J.C.; Santos-Ocaña, C.; Navas, P. Is coenzyme Q a key factor in aging? Mech. Ageing Dev. 2010, 131, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, F.L.; Sun, I.L.; Sun, E.E. The essential functions of coenzyme Q. Clin. Investig. 1993, 71 (Suppl. S8), S55–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, V.; Serbinova, E.; Packer, L. Antioxidant effects of ubiquinones in microsomes and mitochondria are mediated by tocopherol recycling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 169, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, A.; Sohal, R.S. Electron transport-linked ubiquinone-dependent recycling of alpha-tocopherol inhibits autooxidation of mitochondrial membranes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 352, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D.; Bowry, V.W.; Stocker, R. Dietary supplementation with coenzyme Q10 results in increased levels of ubiquinol-10 within circulating lipoproteins and increased resistance of human low-density lipoprotein to the initiation of lipid peroxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1126, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.J.; Porteous, C.M.; Gane, A.M.; Murphy, M.P. Delivery of bioactive molecules to mitochondria in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5407–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, M.P.; Smith, R.A.J. Targeting Antioxidants to Mitochondria by Conjugation to Lipophilic Cations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 629–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gane, E.J.; Weilert, F.; Orr, D.W.; Keogh, G.F.; Gibson, M.; Lockhart, M.M.; Frampton, C.M.; Taylor, K.M.; Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant mitoquinone decreases liver damage in a phase ii study of hepatitis c patients. Liver. Int. 2010, 30, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirilli, I.; Damiani, E.; Dludla, P.V.; Hargreaves, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Millichap, L.E.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Tiano, L. Role of Coen-zyme Q10 in Health and Disease: An Update on the Last 10 Years (2010–2020). Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testai, L.; Martelli, A.; Flori, L.; Cicero, A.; Colletti, A. Coenzyme Q10: Clinical Applications beyond Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Felker, G.M. Coenzyme Q10 and Heart Failure: A State-of-the-Art Review. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2016, 9, e002639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Maraver, J.; Cordero, M.D.; Oropesa-Avila, M.; Vega, A.F.; de la Mata, M.; Pavon, A.D.; Alcocer-Gomez, E.; Calero, C.P.; Paz, M.V.; Alanis, M.; et al. Clinical applications of coenzyme Q10. Front. Biosci. 2014, 19, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zozina, V.I.; Covantev, S.; Goroshko, O.A.; Krasnykh, L.M.; Kukes, V.G. Coenzyme Q10 in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases: Current State of the Problem. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2018, 14, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebrecht, S.; Chan, D.Y.L.; Rosenfeld, F.; Lin, K.W. Coenzyme Q10 and ubiquinol for physical performance. In Coenzyme Q10: From Fact to Fiction; Hargreaves, I., Ed.; Nova Science Pub Inc.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Malm, C.; Svensson, M. Effects of Ubiquinone-10 Supplementation on Physical Performance in Humans. In Coenzyme Q: Molecular Mechanisms in Health and Disease, 1st ed.; Kagan, V.E., Quinn, P.J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.; Díaz-Castro, J.; Pulido-Moran, M.; Kajarabille, N.; Guisado, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Exercise in Healthy Humans: A Systematic Review. Curr. Drug Metab. 2016, 17, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, D142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, B.; Catalá-López, F.; Moher, D. La extensión de la declaración PRISMA para revisiones sistemáticas que incorporan metaanálisis en red: PRISMA-NMA [The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA]. Med. Clin. 2016, 147, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadio, E.; Palermo, R.; Peloni, G.; Littarru, G.P. Effect of CoQ10 administration on V02max and diastolic function in athletes. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Littarru, G.P., Yamagami, T., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Armanfar, M.; Jafari, A.; Dehghan, G.R.; Abdizadeh, L. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on exercise-induced response of inflammatory indicators and blood lactate in male runners. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2015, 29, 202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonetti, A.; Solito, F.; Carmosino, G.; Bargossi, A.M.; Fiorella, P.L. Effect of ubidecarenone oral treatment on aerobic power in mid-dle-aged trained subjects. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2000, 40, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, B.; Clarkson, P.M.; Freedson, P.S.; Kohl, R.L. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Exercise Performance, VO2max, and Lipid Peroxidation in Trained Cyclists. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1991, 1, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerioli, G.; Tirelli, F.; Musiani, L. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 on the metabolic Response to work. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Littarru, G.P., Yamagami, T., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 521–524. [Google Scholar]

- Cinquegrana, G.; Meccariello, P.; Spinelli, L.; Romano, M.; Sotgiu, P.; Cristiano, C.; Ferrara, M.; Giardino, L. Effetti del coenzima Q10 sulla tolleranza all’esercizio fisico e sulla performance cardiaca in soggetti normali non allenati [Effects of coenzyme Q10 on physical exercise tolerance and cardiac performance in normal untrained subjects]. Clin. Ter. 1987, 123, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocoi-Pop, R.; Tache, S.; Bondor, C. The effect of Coenzyme Q10 administration on effort capacity of athletes (Note I). Palestri-ca Milen III—Civilizaţie Şi Sport 2009, 10, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, M.; Iosia, M.; Buford, T.; Shelmadine, B.; Hudson, G.; Kerksick, C.; Rasmussen, C.; Greenwood, M.; Leutholtz, B.; Willoughby, D.; et al. Effects of acute and 14-day coenzyme Q10 supplementation on exercise performance in both trained and untrained individuals. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2008, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Castro, J.; Guisado, R.; Kajarabille, N.; García, C.; Guisado, I.M.; de Teresa, C.; Ochoa, J.J. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation ameliorates inflammatory signaling and oxidative stress associated with strenuous exercise. Eur. J. Nutr. 2011, 51, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnic, F.; Riera, J.; Artuch, R.; Jou, C.; Codina, A.; Montero, R.; Paredes-Fuentes, A.J.; Domingo, J.C.; Banquells, M.; Riva, A.; et al. Efficient Muscle Distribution Reflects the Positive Influence of Coenzyme Q10 Phytosome in Healthy Aging Athletes after Stressing Exercise. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2020, 3, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, A.; Tofighi, A.; Asri-Rezaei, S.; Bazargani-Gilani, B. The effect of short-term coenzyme Q10supplementation and pre-cooling strategy on cardiac damage markers in elite swimmers. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fiorella, P.L.; Bargossi, A.M.; Grossi, G.; Motta, R.; Senaldi, R.; Battino, M.; Sassi, S.; Sprovieri, G.; Lubich, T.; Folkers, K.; et al. Metabolic effects of coenzyme Q10 treatment in high level athletes. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Littarru, G.P., Yamagami, T., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, M.J.A. Efecto del Phlebodium decumanum y de la coenzyma Q10 sobre el rendimiento deportivo en jugadores profesionales de voleibol. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss, K.; Hamm, M.; Littarru, G.P.; Folkers, K.; Enzmann, F. Steigerung der körperlichen Leistungsfähigkeit von Ausdauerathleten mit Hilfen von Q10 Monopräparat. In Energie und Schutz Coenzym Q10 Fakten und Perspektivem in der Biologie und Medizin; Littarru, G.P., Ed.; Litografica Iride: Rome, Italy, 2004; pp. 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gökbel, H.; Gül, I.; Belviranl, M.; Okudan, N. The Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Performance During Repeated Bouts of Supramaximal Exercise in Sedentary Men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokbel, H.; Turk, S.; Okudan, N.; Atalay, H.; Belviranli, M.; Gaipov, A.; Solak, Y. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Exercise Performance and Markers of Oxidative Stress in Hemodialysis Patients: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Am. J. Ther. 2016, 23, e1736–e1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, G.; Ballardini, E.; Lippa, S.; Oradei, A.; Litarru, G. Effetto della somministrazione di Ubidecarenone nel consumo massimo di ossigeno e sulla performance fisica in un gruppo di giovani ciclisti. Med. Sport 1987, 40, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Gül, I.; Gökbel, H.; Belviranli, M.; Okudan, N.; Büyükbaş, S.; Başarali, K. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in plasma after repeated bouts of supramaximal exercise: The effect of coenzyme Q10. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2011, 51, 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.-C.; Chang, P.-S.; Chen, H.-W.; Lee, P.-F.; Chang, Y.-C.; Tseng, C.-Y.; Lin, P.-T. Ubiquinone Supplementation with 300 mg on Glycemic Control and Antioxidant Status in Athletes: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikkonen, J.; Kosonen, L.; Nyyssönen, K.; Porkkala-Sarataho, E.; Salonen, R.; Korpela, H.; Salonen, J.T. Effect of combined coenzyme Q10 and d-α-tocopheryl acetate supplementation on exercise-induced lipid peroxidation and muscular damage: A placebo-controlled double-blind study in marathon runners. Free Radic. Res. 1998, 29, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, R.; Fogelholm, M.; Himberg, J.-J.; Laakso, J.; Salorinne, Y. Ubiquinone supplementation and exercise capacity in trained young and older men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995, 72, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelarungrayub, D.; Sawattikanon, N.; Klaphajone, J.; Pothongsunan, P.; Bloomer, R.J. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation Decreases Oxidative Stress and Improves Physical Performance in Young Swimmers: A Pilot Study. Open Sports Med. J. 2010, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malm, C.; Svensson, M.; Sjoberg, B.; Ekblom, B.; Sjodin, B. Supplementation with ubiquinone-10 causes cellular damage during intense exercise. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1996, 157, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.; Svensson, M.; Ekblom, B.; Sjödin, B. Effects of ubiquinone-10 supplementation and high intensity training on physical performance in humans. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1997, 161, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, K.; Tanaka, M.; Nozaki, S.; Mizuma, H.; Ataka, S.; Tahara, T.; Sugino, T.; Shirai, T.; Kajimoto, Y.; Kuratsune, H.; et al. Antifatigue effects of coenzyme Q10 during physical fatigue. Nutrition 2008, 24, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.N.; Mizuno, M.; Ratkevicius, A.; Mohr, T.; Rohde, M.; Mortensen, S.A.; Quistorff, B. No Effect of Antioxidant Supplementation in Triathletes on Maximal Oxygen Uptake, 31P-NMRS Detected Muscle Energy Metabolism and Muscle Fatigue. Int. J. Sports Med. 1999, 20, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okudan, N.; Belviranli, M.; Torlak, S. Coenzyme Q10 does not prevent exercise-induced muscle damage and oxidative stress in sedentary men. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2018, 58, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Östman, B.; Sjödin, A.; Michaëlsson, K.; Byberg, L. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation and exercise-induced oxidative stress in humans. Nutrition 2012, 28, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.A.; Costill, D.L.; Zachwieja, J.J.; Krzeminski, K.; Fink, W.J.; Wagner, E.; Folkers, K. The Effect of Oral Coenzyme Q10 on the Exercise Tolerance of Middle-Aged, Untrained Men. Int. J. Sports Med. 1995, 16, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, I.P.; Bazzarre, T.L.; Murdoch, S.D.; Goldfarb, A. Effects of Coenzyme Athletic Performance System as an Ergogenic Aid on Endurance Performance to Exhaustion. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1992, 2, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svensson, M.; Malm, C.; Tonkonogi, M.; Ekblom, B.; Sjödin, B.; Sahlin, K. Effect of Q10 Supplementation on Tissue Q10 Levels and Adenine Nucleotide Catabolism During High-Intensity Exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1999, 9, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauler, P.; Ferrer, M.D.; Sureda, A.; Pujol, P.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Supplementation with an antioxidant cocktail containing coenzyme Q prevents plasma oxidative damage induced by soccer. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.D.; Tauler, P.; Sureda, A.; Pujol, P.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. A Soccer Match’s Ability to Enhance Lymphocyte Capability to Produce ROS and Induce Oxidative Damage. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2009, 19, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanfraechem, J.; Folkers, K. Coenzyme Q10 and physical performance. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Yamamura, Y., Eds.; Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; Volume 3, pp. 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, S.B.; Zhou, S.; Weatherby, R.P.; Robson, S.J. Does Exogenous Coenzyme Q10 Affect Aerobic Capacity in Endurance Athletes? Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1997, 7, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyss, V.; Lubich, T.; Ganzit, G.; Cesaretti, D.; Fiorella, P.; Dei Rocini, C.; Battino, M. Remarks of prolonged ubiquinone administration in physical exercise. In Highlights in Ubiquinone Research; Lenaz, G., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1990; pp. 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Yamabe, H.; Fukuzaki, H. The beneficial effect of coenzyme Q10 on the impaired aerobic function in middle aged women without organic disease. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Littarru, G.P., Yamagami, T., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 535–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ylikoski, T.; Piirainen, J.; Hanninen, O.; Penttinen, J. The effect of coenzyme Q10 on the exercise performance of cross-country skiers. Mol. Asp. Med. 1997, 18, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppilli, P.; Merlino, B.; De Luca, A.; Palmieri, V.; Santini, C.; Vannicelli, R.; Littarru, G.P. Influence of Coenzyme-Q10 on physical work capacity in athletes, sedentary people and patients with mitochondrial disease. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Littarru, G.P., Yamagami, T., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A.; Moritani, T. Influence of CoQ10 on autonomic nervous activity and energy metabolism during exercise in healthy subjects. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2008, 54, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Davie, A.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Brushett, D. Muscle and plasma coenzyme Q10 concentration, aerobic power and exercise economy of healthy men in response to four weeks of supplementation. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2005, 45, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zuliani, U.; Bonetti, A.; Campana, M.; Cerioli, G.; Solito, F.; Novarini, A. The influence of ubiquinone (Co Q10) on the metabolic response to work. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1989, 29, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.; MacRae, C.L.; Broome, S.C.; D’Souza, R.F.; Narang, R.; Wang, H.W.; Mori, T.A.; Hickey, A.J.R.; Mitchell, C.J.; Merry, T.L. MitoQ and CoQ10 supplementation mildly suppresses skeletal muscle mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide levels without impacting mitochondrial function in middle-aged men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alf, D.; Schmidt, M.E.; Siebrecht, S.C. Ubiquinol supplementation enhances peak power production in trained athletes: A double-blind, placebo controlled study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2013, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloomer, R.J.; Canale, R.E.; McCarthy, C.G.; Farney, T.M. Impact of Oral Ubiquinol on Blood Oxidative Stress and Exercise Performance. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 465020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diaz-Castro, J.; Mira-Rufino, P.J.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Chirosa, I.; Chirosa, J.L.; Guisado, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Ubiquinol supplementation modulates energy metabolism and bone turnover during high intensity exercise. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7523–7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Castro, J.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Chirosa, I.; Chirosa, L.J.; Guisado, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Beneficial Effect of Ubiquinol on Hematological and Inflammatory Signaling during Exercise. Nutrients 2020, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kizaki, K.; Terada, T.; Arikawa, H.; Tajima, T.; Imai, H.; Takahashi, T.; Era, S. Effect of reduced coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol) supple-mentation on blood pressure and muscle damage during kendo training camp: A double-blind, randomized controlled study. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2015, 55, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Kon, M.; Tanabe, K.; Akimoto, T.; Kimura, F.; Tanimura, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Okamoto, T.; Kono, I. Reducing exercise-induced muscular injury in kendo athletes with supplementation of coenzyme Q10. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunching, S.; Nararatwanchai, T.; Chalermchai, T.; Wongsupasawat, K.; Sitiprapaporn, P.; Thipsiriset, A. The effects of ubiquinol supplementation on clinical parameters and physical performance in trained men. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 44, 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Galeazzi, R.; Antonicelli, R.; Marcheggiani, F.; Cirilli, I.; Bacchetti, T.; Tiano, L. Effect of ubiquinol supplementation on biochemical and oxidative stress indexes after intense exercise in young athletes. Redox Rep. 2018, 23, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.; Diaz-Castro, J.; Pulido-Moran, M.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Kajarabille, N.; Chirosa, I.; Guisado, I.M.; Chirosa, L.J.; Guisado, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Short-term ubiquinol supplementation reduces oxidative stress associated with strenuous exercise in healthy adults: A randomized trial. BioFactors 2016, 42, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nagato, S.; Sakuraba, K.; Morio, K.; Sawaki, K. Short-term ubiquinol-10 supplementation alleviates tissue damage in muscle and fatigue caused by strenuous exercise in male distance runners. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2021, 91, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shill, D.D.; Southern, W.M.; Willingham, T.B.; Lansford, K.A.; McCully, K.K.; Jenkins, N.T. Mitochondria-specific antioxidant supplementation does not influence endurance exercise training-induced adaptations in circulating angiogenic cells, skeletal muscle oxidative capacity or maximal oxygen uptake. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 7005–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.; Hughes, C.M.; Cobley, J.N.; Davison, G.W. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ, attenuates exercise-induced mitochondrial DNA damage. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broome, S.C.; Braakhuis, A.J.; Mitchell, C.J.; Merry, T.L. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant supplementation improves 8 km time trial performance in middle-aged trained male cyclists. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J.; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harbour, R.; Miller, J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ 2001, 323, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro Scale for Rating Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paredes-Fuentes, A.J.; Montero, R.; Codina, A.; Jou, C.; Fernández, G.; Maynou, J.; Santos-Ocaña, C.; Riera, J.; Navas, P.; Drobnic, F.; et al. Coenzyme Q10 Treatment Monitoring in Different Human Biological Samples. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cuesta, A.; Cortés-Rodríguez, A.B.; Navas-Enamorado, I.; Lekue, J.A.; Viar, T.; Axpe, M.; Navas, P.; López-Lluch, G. High coenzyme Q10 plasma levels improve stress and damage markers in professional soccer players during competition. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoe, K.; Kitano, M.; Kishida, H.; Kubo, H.; Fujii, K.; Kitahara, M. Study on safety and bioavailability of ubiquinol (Kaneka QH™) after single and 4-week multiple oral administration to healthy volunteers. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 47, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagavan, H.N.; Chopra, R.K. Coenzyme Q10: Absorption, tissue uptake, metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, M.; Mortensen, S.; Rassing, M.; Møller-Sonnergaard, J.; Poulsen, G.; Rasmussen, S. Bioavailability of four oral Coenzyme Q10 formulations in healthy volunteers. Mol. Asp. Med. 1994, 15, s273–s280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Obermüller-Jevic, U.C.; Hasselwander, O.; Bernhardt, J.; Biesalski, H.K. Comparison of the relative bioavailability of different coenzyme Q10formulations with a novel solubilizate (Solu™ Q10). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 57, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrangolini, G.; Ronchi, M.; Frattini, E.; De Combarieu, E.; Allegrini, P.; Riva, A. A New Food-grade Coenzyme Q10 Formulation Improves Bioavailability: Single and Repeated Pharmacokinetic Studies in Healthy Volunteers. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Bysted, A.; Hølmer, G. Coenzyme Q10 in the diet-daily intake and relative bioavailability. Mol. Asp. Med. 1997, 18, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakuša, T.; Kristl, A.; Roškar, R. Stability of Reduced and Oxidized Coenzyme Q10 in Finished Products. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Niaz, M.A.; Kumar, A.; Sindberg, C.D.; Moesgaard, S.; Littarru, G.P. Effect on absorption and oxidative stress of different oral Coenzyme Q10dosages and intake strategy in healthy men. BioFactors 2005, 25, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaz, G. Coenzyme Q saturation kinetics of mitochondrial enzymes: Theory, experimental aspects and biomedical implica-tions. In Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q; Folkers, K., Yamagami, T., Littarru, G.P., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux, S.L.; Florkowski, C.M.; Lever, M.; George, P.M. Biological Variation of Coenzyme Q10. Clin. Chem. 2005, 51, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duncan, A.J.; Heales, S.J.; Mills, K.; Eaton, S.; Land, J.M.; Hargreaves, I.P. Determination of Coenzyme Q10 Status in Blood Mononuclear Cells, Skeletal Muscle, and Plasma by HPLC with Di-Propoxy-Coenzyme Q10 as an Internal Standard. Clin. Chem. 2005, 51, 2380–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okamoto, T.; Mizuta, K.; Mizobuchi, S.; Usui, A.; Takahashi, T.; Fujimoto, S.; Kishi, T. Decreased serum ubiquinol-10 levels in healthy subjects during exercise at maximal oxygen uptake. BioFactors 2000, 11, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battino, M.; Amadio, E.; Oradei, A.; Littarru, G. Metabolic and antioxidant markers in the plasma of sportsmen from a Mediterranean town performing non-agonistic activity. Mol. Asp. Med. 1997, 18, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, L.K.; Kamzalov, S.; Rebrin, I.; Bayne, A.-C.V.; Jana, C.K.; Morris, P.; Forster, M.J.; Sohal, R.S. Effects of coenzyme Q10 administration on its tissue concentrations, mitochondrial oxidant generation, and oxidative stress in the rat. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.L.; Huang, Y.H.; Kao, C.L.; Yang, D.M.; Lee, H.C.; Chou, H.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Chiou, G.Y.; Chen, L.H.; Yang, Y.P.; et al. A novel mechanism of coenzyme Q10 protects against human endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced injury by modulating NO-related pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belviranlı, M.; Okudan, N. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 Alone and in Combination with Exercise Training on Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Rats. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2018, 88, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, R.S.; Forster, M.J. Coenzyme Q, oxidative stress and aging. Mitochondrion 2007, 7, S103–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Larriva, A.P.A.-D.; Limia-Perez, L.; Romero-Cabrera, J.L.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; López-Miranda, J. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation for the Reduction of Oxidative Stress: Clinical Implications in the Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y. Coenzyme Q10 redox balance and a free radical scavenger drug. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 595, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.J.; Quintanilha, A.T.; Brooks, G.A.; Packer, L. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 107, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwenburgh, C. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Exercise. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, M.B.; Haack, K.E.; Franchek, K.M.; Valberg, P.A.; Kobzik, L.; West, M.S. Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. I. Intracellular oxidant kinetics and fatigue in vitro. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992, 73, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiló, A.; Tauler, P.; Fuentespina, E.; Tur, J.A.; Córdova, A.; Pons, A. Antioxidant response to oxidative stress induced by exhaustive exercise. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 84, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravst, I.; Rodriguez Aguilera, J.C.; Cortes Rodriguez, A.B.; Jazbar, J.; Locatelli, I.; Hristov, H.; Žmitek, K. Comparative Bioavailability of Different Coenzyme Q10 Formulations in Healthy Elderly Individuals. Nutrients 2020, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Nosaka, K.; Braun, B. Muscle function after exercise-induced muscle damage and rapid adaptation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992, 24, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiidus, P.M. Radical species in inflammation and overtraining. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1998, 76, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova-Martínez, A.; Caballero-García, A.; Bello, H.J.; Perez-Valdecantos, D.; Roche, E. Effects of Eccentric vs. Concentric Sports on Blood Muscular Damage Markers in Male Professional Players. Biology 2022, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proske, U.; Morgan, D.L. Muscle damage from eccentric exercise: Mechanism, mechanical signs, adaptation and clinical applications. J. Physiol. 2001, 537, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Bo, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 on Markers of Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Córdova, A.; Sureda, A.; Pons, A.; Alvarez-Mon, M. Modulation of TNF-α, TNF-α receptors and IL-6 after treatment with AM3 in professional cyclists. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2015, 55, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova-Martínez, A.; Caballero-García, A.; Bello, H.; Pérez-Valdecantos, D.; Roche, E. Effect of Glutamine Supplementation on Muscular Damage Biomarkers in Professional Basketball Players. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.C.; Pons, M.M.; Gomila, A.S.; Marí, J.A.T.; Biescas, A.P. Changes in circulating cytokines and markers of muscle damage in elite cyclists during a multi-stage competition. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2014, 35, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Suzuki, K.; Coombes, J. The influence of antioxidant supplementation on markers of inflammation and the relationship to oxidative stress after exercise. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007, 18, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.L.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J. Role of nuclear factor κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in exercise-induced antioxidant enzyme adaptation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnic, F. Las agujetas, ¿una entidad clínica con nombre inapropiado? (Mecanismos de aparición, evolución y tratamiento). Apunts. Medicina de l’Esport 1989, 26, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, A.; Monserrat, J.; Villa, G.; Reyes, E.; Soto, M.A.-M. Effects of AM3 (Inmunoferon®) on increased serum concentrations of interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor receptors I and II in cyclists. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwane, J.A.; Johnson, S.R.; Vandenakker, C.B.; Armstrong, R.B. Delayed-onset muscular soreness and plasma CPK and LDH activities after downhill running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983, 15, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Suzuki, K.; Wilson, G.; Hordern, M.; Nosaka, K.; Mackinnon, L.; Coombes, J.S. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage, Plasma Cytokines, and Markers of Neutrophil Activation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimomura, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Sugiyama, S.; Hanaki, Y.; Ozawa, T. Protective effect of coenzyme Q10 on exercise-induced muscular injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 176, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, P.; Maffulli, N.; Limongelli, F.M. Creatine kinase monitoring in sport medicine. Br. Med. Bull. 2007, 81–82, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, A.L.; Oliveira, V.N.; Agostini, G.G.; Oliveira, R.J.; Oliveira, A.C.; White, G.E.; Wells, G.D.; Teixeira, D.N.; Espindola, F.S. Exercise Intensity and Recovery: Biomarkers of Injury, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, P.; Maffulli, N.; Buonauro, R.; Limongelli, F.M. Serum Enzyme Monitoring in Sports Medicine. Clin. Sports Med. 2008, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Clarkson, P.M. Plasma Creatine Kinase Activity and Glutathione after Eccentric Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, M.F.; Graham, S.M.; Baker, J.S.; Bickerstaff, G.F. Creatine-Kinase- and Exercise-Related Muscle Damage Implications for Muscle Performance and Recovery. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 960363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vincent, H. The Effect of Training Status on the Serum Creatine Kinase Response, Soreness and Muscle Function Following Resistance Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 1997, 28, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horská, A.; Fishbein, K.W.; Fleg, J.L.; Spencer, R.G.S. The relationship between creatine kinase kinetics and exercise intensity in human forearm is unchanged by age. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 279, E333–E339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totsuka, M.; Nakaji, S.; Suzuki, K.; Sugawara, K.; Sato, K. Break point of serum creatine kinase release after endurance exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltusnikas, J.; Venckunas, T.; Kilikevicius, A.; Fokin, A.; Ratkevicius, A. Efflux of creatine kinase from isolated soleus muscle de-pends on age, sex and type of exercise in mice. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2015, 14, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baumert, P.; Lake, M.J.; Stewart, C.; Drust, B.; Erskine, R.M. Genetic variation and exercise-induced muscle damage: Implications for athletic performance, injury and ageing. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 1595–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miyoshi, K.; Kawai, H.; Iwasa, M.; Kusaka, K.; Nishino, H. Autosomal recessive distal muscular dystrophy as a new type of progressive muscular dystrophy. Seventeen cases in eight families including an autopsied case. Brain 1986, 109, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortobágyi, T.; Denahan, T. Variability in Creatine Kinase: Methodological, Exercise, and Clinically Related Factors. Endoscopy 1989, 10, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, K.; Newton, M.; Sacco, P. Delayed-onset muscle soreness does not reflect the magnitude of eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2002, 12, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, J.; McShane, J.M. Postcompetition elevation of muscle enzyme levels in professional football players. MedGenMed 2000, 2, E4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linnane, A.W.; Kopsidas, G.; Zhang, C.; Yarovaya, N.; Kovalenko, S.; Papakostopoulos, P.; Eastwood, H.; Graves, S.; Richardson, M. Cellular Redox Activity of Coenzyme Q 10: Effect of CoQ 10 Supplementation on Human Skeletal Muscle. Free Radic. Res. 2002, 36, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, R.I.; Gómez-Díaz, C.; Burón, M.I.; Alcaín, F.J.; Navas, P.; Villalba, J.M. Enhanced anti-oxidant protection of liver membranes in long-lived rats fed on a coenzyme Q10-supplemented diet. Exp. Gerontol. 2005, 40, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, A.; Kuźniar, J.; Sawicka, E.; Marchewka, Z.; Lembas-Bogaczyk, J.; Sajewicz, W.; Boratyńska, M. Oxidative stress and coenzyme Q10 supplementation in renal transplant recipients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2004, 36, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billat, V. Fisiología y Metodología del Entrenamiento. de la Teoría a la Práctica; Paidotribo: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Howley, E.T. Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billat, V.; Renoux, J.C.; Pinoteau, J.; Petit, B.; Koralsztein, J.P. Reproducibility of running time to exhaustion at VO2max in subelite runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, T.M.; Cheung, S.S.; Jacobs, I. Variability of Time to Exhaustion During Submaximal Exercise. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995, 20, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Freedson, P. Intraindividual Variation of Running Economy in Highly Trained and Moderately Trained Males. Endoscopy 1997, 18, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, D.C.; Burnley, M.; Vanhatalo, A.; Rossiter, H.B.; Jones, A.M. Critical Power: An Important Fatigue Threshold in Exercise Physiology. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 2320–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McClave, S.A.; LeBlanc, M.; Hawkins, S.A. Sustainability of Critical Power Determined by a 3-Minute All-Out Test in Elite Cyclists. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 3093–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipp, B.J.; Ward, S.A.; Rossiter, H. Pulmonary O2 Uptake during Exercise: Conflating Muscular and Cardiovascular Responses. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushel, R.; Gnaiger, E.; Calbet, J.A.; Gonzalez-Alonso, J.; Wright-Paradis, C.; Sondergaard, H.; Ara, I.; Helge, J.W.; Saltin, B. Muscle mitochondrial capacity exceeds maximal oxygen delivery in humans. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruusgaard, J.C.; Johansen, I.B.; Egner, I.M.; Rana, Z.A.; Gundersen, K. Myonuclei acquired by overload exercise precede hypertrophy and are not lost on detraining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15111–15116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egner, I.M.; Bruusgaard, J.C.; Eftestøl, E.; Gundersen, K. A cellular memory mechanism aids overload hypertrophy in muscle long after an episodic exposure to anabolic steroids. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 6221–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, P.E.; Tang, P.H.; Degrauw, A.J.; Miles, M.V. Clinical Laboratory Monitoring of Coenzyme Q10 Use in Neurologic and Muscular Diseases. Pathol. Patterns Rev. 2004, 121 (Suppl. S1), S113–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littarru, G.; Battino, M.; Tomasetti, M.; Mordente, A.; Santini, S.; Oradei, A.; Manto, A.; Ghirlanda, G. Metabolic implications of Coenzyme Q10 in red blood cells and plasma lipoproteins. Mol. Asp. Med. 1994, 15, s67–s72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozawa, S.; Araki, Y.; Oda, T. Stabilizing effects of coenzyme Q10 on potassium ion release, membrane potential and fluidity of rabbit red blood cells. Acta Med. Okayama 1980, 34, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wani, M.R.; Shadab, G.G.H.A. Coenzyme Q10 protects isolated human blood cells from TiO2 nanoparticles induced oxidative/antioxidative imbalance, hemolysis, cytotoxicity, DNA damage and mitochondrial impairment. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3367–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, Y.; Jia, H.; Zhang, L.; Cao, X.; Zuo, X.; Cai, G.; Chen, X. Associations of coenzyme Q10 with endothelial function in hemodialysis patients. Nephrology 2020, 26, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Xu, Z.; Hosoe, K.; Kubo, H.; Miyahara, H.; Dai, J.; Mori, M.; Sawashita, J.; Higuchi, K. Coenzyme Q10 Prevents Senescence and Dysfunction Caused by Oxidative Stress in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3181759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, M.J.; Pattee, G.L.; Strong, G.L.P.M.J. Creatine and coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000, 1 (Suppl. S4), S17–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Anderson, S.D.; Schofield, R.S. Coenzyme q10 and creatine in heart failure: Micronutrients, macrobenefit? Clin. Cardiol. 2011, 34, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guescini, M.; Tiano, L.; Genova, M.L.; Polidori, E.; Silvestri, S.; Orlando, P.; Fimognari, C.; Calcabrini, C.; Stocchi, V.; Sestili, P. The Combination of Physical Exercise with Muscle-Directed Antioxidants to Counteract Sarcopenia: A Biomedical Rationale for Pleiotropic Treatment with Creatine and Coenzyme Q10. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7083049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mori, T.A.; Burke, V.; Puddey, I.B.; Irish, A.; Cowpland, C.A.; Beilin, L.J.; Dogra, G.K.; Watts, G. The effects of ω3 fatty acids and coenzyme Q10 on blood pressure and heart rate in chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharská, J.; Poništ, S.; Vančová, O.; Gvozdjáková, A.; Uličná, O.; Slovák, L.; Taghdisiesfejir, M.; Bauerová, K. Treatment With Coenzyme Q10, ω-3-Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Combination Improved Bioenergetics and Levels of Coenzyme Q9 and Q10 in Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria in Experimental Model of Arthritis. Physiol. Res. 2021, 70, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, G.I. Combination of Omega 3 and Coenzyme Q10 Exerts Neuroprotective Potential Against Hypercholesterolemia-Induced Alzheimer’s-Like Disease in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.-J.; Ko, W.-K.; Han, S.W.; Kim, D.-S.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Park, H.-K.; Kwon, I.K. Antioxidants, like coenzyme Q10, selenite, and curcumin, inhibited osteoclast differentiation by suppressing reactive oxygen species generation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 418, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parohan, M.; Sarraf, P.; Javanbakht, M.H.; Foroushani, A.R.; Ranji-Burachaloo, S.; Djalali, M. The synergistic effects of nano-curcumin and coenzyme Q10 supplementation in migraine prophylaxis: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 24, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadasu, V.R.; Wadsworth, R.M.; Kumar, M.N.V.R. Protective effects of nanoparticulate coenzyme Q10 and curcumin on inflammatory markers and lipid metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: A possible remedy to diabetic complications. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2011, 1, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.M.; Peeling, P. Methodologies for Investigating Performance Changes With Supplement Use. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grossman, J.; Mackenzie, F.J. The Randomized Controlled Trial: Gold standard, or merely standard? Perspect. Biol. Med. 2005, 48, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Riebe, D.; Ehrman, J.K.; Liguori, G.; Magal, M. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; Kluwer, W., Ed.; American College of Sports Medicine: Filadelfia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Geifman, N.; Cohen, R.; Rubin, E. Redefining meaningful age groups in the context of disease. AGE 2013, 35, 2357–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beyer, R.E.; Morales-Corral, P.G.; Ramp, B.J.; Kreitman, K.R.; Falzon, M.J.; Rhee, S.Y.S.; Kuhn, T.W.; Stein, M.; Rosenwasser, M.J.; Cartwright, K.J. Elevation of tissue coenzyme Q (ubiquinone) and cytochrome c concentrations by endurance exercise in the rat. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984, 234, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gohil, K.; Rothfuss, L.; Lang, J.; Packer, L. Effect of exercise training on tissue vitamin E and ubiquinone content. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987, 63, 1638–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Svensson et al. [68] | Díaz-Castro et al. [83,84] | Kizaki et al. [85] | Kon et al. [86] | Sarmiento et al. [89] | Suzuki et al. [90] | Braun et al. [41] | Ho et al. [56] | Weston et al. [72] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria 1 * | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Criteria 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 9. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Criteria 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PEDro Score | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| Reference | Molecule | CoQ10 mg/d | Duration (d: Days) | Placebo | n Total/CoQ10 | Type of Subjects | Sex | Sport/Activity | Exercise Testing | Age (Years) | Impact on Phys./Sport Perf. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Svensson et al. (1999) | [68] | Ubiquinone | 120 | 20 d | Yes | 17/9 | Well trained subjects | Male | - | Graded max and Anaerobic tests | 28 ± 5 | No |

| Díaz-Castro et al. (2020) | [83,84] | Ubiquinol | 200 | 14 d | Yes | 100/50 | Well trained subjects | Male | Firemen | Circuit edurance exercises | 39 ± 1 | - |

| Kizaki et al. (2015) | [85] | Ubiquinol | 600 | 11 d | Yes | 32/17 | Well trained subjects | Male | Kendo | 4 training days | 20 ± 1 | No |

| Kon et al. (2008) | [86] | Ubiquinol | 300 | 20 d | Yes | 18/10 | High level | Male | Kendo | Muscle injury induced exercise | 20 ± 1 | Yes |

| Sarmiento et al. (2016) | [89] | Ubiquinol | 200 | 14 d | Yes | 100/50 | Well trained subjects | Male | Firemen | Circuit edurance exercises | 39 ± 9 | - |

| Suzuki et al. (2021) | [90] | Ubiquinol | 300 | 12 d | Yes | 16/8 | Well trained subjects | Male | Distance runners | 25 & 40 K races | 20 ± 2 | Yes |

| Braun et al. (1991) | [41] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 56 d | Yes | 12/6 | High level | Male | Cyclists | Graded max test | 22 ± 2 | No |

| Ho et al. (2020) | [56] | Ubiquinone | 300 | 84 d | Yes | 31/15 | Moderately trained subjects | Male & Female | Soccer & Taekwondo | None | 20 ± 1 | - |

| Weston et al. (1997) | [72] | Ubiquinone | ≃70 | 28 d | Yes | 18/6 | High level | Male | Cyclists and Triathletes | Graded max. | 25 ± 3 | No |

| Reference | Change CoQ10 Total | Measured Parameters and Effects of CoQ10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μg/mL) | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μmol/mol Chol) | Muscle Pre ➝ Post (nmol/g Protein) | Inflammatory Pattern | Antioxidant Pattern | Physical Performance | Sport Performance | Muscle Injury | Other | |

| Svensson et al. (1999) | Plasma ↑ Muscle ↔ | 0.74 ➝ 1.23 | 40.8 ➝ 44.2 mgl/kg | HX, MDA, UA ↔ | ||||||

| Díaz-Castro et al. (2020) | Plasma ↑ | 1.00 ➝ 5.22 | VEGF, NO, EGF, IL-1ra, IL-10 ↑, and IL-1, IL-8, MCP-1 ↓ | PTH, OC, OPG, phosphatase al., leptin, insulin, noradrenaline and PGC-1α ↑, | ||||||

| Kizaki et al. (2015) | Plasma↑ | 0.7 ➝ 10.8 | CK, Mb ↔, | |||||||

| Kon et al. (2008) | Plasma↑ | ≃0.8 ➝ ≃3.8 | LPO ↓ | CK, Mb ↓ | ||||||

| Sarmiento et al. (2016) | Plasma ↑ | 0.9 ➝ 4.5 | NO ↓ | hydroperoxydes Isoprostanes, oxidized LDL, TAC ↑ | ||||||

| Suzuki et al. (2021) | Plasma ↑ | 0.7 ➝ 5.6 | Perception of fatigue ↓ | CK, ALT, LDH ↓ | ||||||

| Braun et al. (1991) | Plasma ↑ | ≃0.8 ➝ 1.5 | MDA ↓ (NS) | Total work load, VO2peak, HR ↔ | CoQ10 postexercise ↑ | |||||

| Ho et al. (2020) | Plasma ↑ | 0.57 ➝ 1.14 | 130 ➝ 270 | MDA ↓, TAC ↔ | Improve glycemic control | |||||

| Weston et al. (1997) | Plasma ↑ | 0.9 ➝ 2.0 | Oxygen uptake at 6 min ↑, VO2max, max power, Anaerobic threshold, and HRTime ↔ | |||||||

| Reference | Molecule | CoQ10 mg/d | Duration (d: Days) | Placebo | n Total/CoQ10 | Type of Subjects | Sex | Sport/Activity | Exercise Testing | Age (Years) | Impact on Phys./Sport Perf. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alf et al. (2013) | [81] | Ubiquinol | 300 | 42 d | Yes | 100/50 | High level | Male & Female | Olympic Athletes | Cycling submaximal test | 19 ± 3 | Yes/Yes |

| Bloomer et al. (2012) | [82] | Ubiquinol | 300 | 28 d | Yes | 15/15 | Well trained subjects | Male & Female | Ns | Graded and Anaerobic max. Tests | 43 ± 10 | No |

| Kunching et al. (in press) | [87] | Ubiquinol | 200 | 42 d | Yes | 29/15 | Moderately trained subjects | Male | Diverse | Indirect max. Test, 1RM and flexibility | 24 ± 2 | Yes |

| Orlando et al. (2018) | [88] | Ubiquinol | 200 | 28 d | Yes | 21/21 | Moderately trained subjects | Male | Rugby | 40 min 85%max. Treadmill | 26 ± 5 | No |

| Pham et al. (2020) | [80] | Ubiquinol | 200 | 42 d | No | 22/22 | Physically active subjects | Male | - | None | 51 ± 1 | - |

| Broome et al. (2021) | [93] | Mitoquinone | 20 | 28 d | Yes | 19/19 | Well trained subjects | Male | Cyclists | 8 km race | 44 ± 4 | Yes |

| Pham et al. (2020) | [80] | Mitoquinone | 20 | 42 d | No | 22/22 | Physically active subjects | Male | - | None | 51 ± 1 | - |

| Shill et al. (2021) | [91] | Mitoquinone | 10 | 21 d | Yes | 20/10 | Physically active subjects | Male | - | Graded max test | 22 ± 1 | No |

| Williamsom et al. (2020) | [92] | Mitoquinone | 20 | 21 d | Yes | 24/12 | Physically active subjects | Male | - | Anaerobic repeated tests | 25 ± 4 | Yes |

| Amadio et al. (1991) | [38] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 40 d | Control | 10/5 | Well trained subjects | Male | Basketball | Submaximal test | 19 ± 5 | Yes |

| Armanfar et al. (2015) | [39] | Ubiquinone | 300–400 | 14 d | Yes | 18/9 | Well trained subjects | Male | Middle distance runners | 3000 m race | 20 ± 3 | No |

| Bonetti et al. (2000) | [40] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 56 d | Yes | 28/14 | Moderately trained subjects and NA | Male | Cyclists | Graded max test | 41 ± 6 | Yes |

| Cerioli (1991) | [42] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 30 d | Ns | 12 | Non active | Male | - | Graded max test | 26 | Yes |

| Cinquegrana et al. (1987) | [43] | Ubiquinone | 60 | 35 d | Yes | 14/14 | Non active | Male | - | Graded max test | 48 ± 3 | |

| Ciocoi-Pop et al. (Note I & II) (2009) | [44] | Ubiquinone | 30 | 21 d | Yes | 10/5 | Well trained subjects | Male | Soccer | Graded max and Anaerobic tests | 19 ± 0 | Yes |

| Cooke et al. (2008) | [45] | Ubiquinone | 200 | 14 d | Yes | 31/21 | Moderately trained subjects and untrained | Male & Female | - | Grade max, Isokinetic, and Anaerobic tests | 26 ± 8 | No |

| Díaz-Castro et al. (2012) | [46] | Ubiquinone | 30 × 2 days, 120 day test | 3 d | Yes | 20/10 | Well trained subjects | Male | - | 50 km running | 41 ± 3 | Yes |

| Reference | Change CoQ10 Total | Measured Parameters and Effects of CoQ10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μg/mL) | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μmol/mol Chol) | Muscle Pre ➝ Post (nmol/g Protein) | Inflammatory Pattern | Antioxidant Pattern | Physical Performance | Sport Performance | Muscle Injury | Other | |

| Alf et al. (2013) | - | Power output ↑ | ||||||||

| Bloomer et al. (2012) | Plasma ↑ | 0.98 ➝ 2.33 | 0.48 ➝ 1.13 | MDA, hydrogen peroxide, | Lactate ↔ | perceived vigour ↔ | ||||

| Kunching et al. (in press) | - | VO2max ml/kg ↑,Max strength ↔ | Sistolic pressure ↓ | |||||||

| Orlando et al. (2018) | Plasma ↔ CoQ10/Chol ↑ | ≃180 ➝ >500 | ROS ↓ | Time to exhaustion, speed ↔ | CK, DNA damage ↔ | |||||

| Pham et al. (2020) | - | H2O2 mit ↓, Isoprost ↔ | ||||||||

| Broome et al. (2021) | - | ROS, Isoprost ↓ | Power output ↑ | Faster time trial. | ||||||

| Pham et al. (2020) | - | H2O2 mit ↓, TAC ↑, Isoprostanes ↔ | ||||||||

| Shill et al. (2021) | - | CDseries, VEGFR2+ and peripheral blood mononuclear cells ↔ | VO2max ↔ | Muscle mitochondrial capacity ↔ | ||||||

| Williamsom et al. (2020) | - | DNA damage ↓ | ||||||||

| Amadio et al. (1991) | Plasma ↑ | 0.9 ➝ 1.6 | VO2max ↑ | Cardiac parameters | ||||||

| Armanfar et al. (2015) | - | TNFa, CRP, IL6 ↓ | CK ↔ | |||||||

| Bonetti et al. (2000) | Plasma ↑ | 0.8 ➝ 2.2 | hypoxanthine, xanthine and inosine ↔ | Max work load ↑ VO2peak, anaerobic threshold and lactate ↔, | ||||||

| Cerioli (1991) | - | Aerobic Capacity↑ | CK ↔ | FFA ↓,Fat metabolism ↑ | ||||||

| Cinquegrana et al. (1987) | - | |||||||||

| Ciocoi-Pop et al. (Note I&II) (2009) | - | MDA ↑, HD ↑ in saliva | VO2max ↑, Anaerobic power ↔ | |||||||

| Cooke et al. (2008) | Plasma ↑ Muscle ↔ | ≃0.6 ➝ ≃2.5 | ≃1.2 ➝ ≃1.4 μg/mg | MDA ↑, SOD ↓ | VO2max, anaerobic capacity, Anaerobic power ↔ | |||||

| Díaz-Castro et al. (2012) | - | IL-6 ↔, 8-OH-dG, TNF-α ↓ | CAT ↑, TAS ↑, GPx ↔, hydroperoxide ↓, isoprostane ↓, | |||||||

| Reference | Molecule | CoQ10 mg/d | Duration (d: Days) | Placebo | n Total/CoQ10 | Type of Subjects | Sex | Sport/Activity | Exercise Testing | Age (Years) | Impact on Phys./Sport Perf. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drobnic et al. (2020) | [47] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 30 d | Control | 20/12 | Well trained subjects | Male | Marathon runners | Treadmill Hot & Humid environment | 55 ± 4 | Yes |

| Emami et al. (2018) | [48] | Ubiquinone | 300 | 14 d | Yes | 36/9 | Well trained subjects | Male | Swimmwers | Swimming training | 18 ± 1 | |

| Fiorella et al. (1991) | [49] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 40 d | Control | 22/11 | Well trained subjects | Male | Athletes | Graded max test + Incremental running test until exhaustion | 29 ± 6 | Yes |

| García-Verazaluce et al. (2015) | [50] | Ubiquinone + | 120 + Phlebodium d. | 28 d | Yes | 30/10 | Well trained subjects | Male | Volleyball | None | 25 ± 2 | Ns |

| Geiss et al. (2004) | [51] | Ubiquinone | 180 | 28 d | Yes | 10/10 | Well trained subjects | Male? | Endurance | Submaximal fatigue test | Ns | Yes |

| Gökbel et al. (2010) | [52] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 56 d | Yes | 15/15 | Non active | Male | Ns | Anaerobic test(Repeated Wingate test) | 20 ± 1 | No |

| Gökbel et al. (2016) | [53] | Ubiquinone | 200 | 98 d | Yes | 23/23 | Patients (hemodyalisis) | Male | Ns | 6 Mins walking test | 47 ± 12 | No |

| Guerra et al. (1987) | [54] | Ubiquinone | 60 | 35 d | Ns | Moderately trained subjects | Male | Cycling | Graded max test. Race 9 km. | Ns | Yes/Yes | |

| Gül et al. (2011) | [55] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 56 d | Yes | 15 | Non active | Male | - | Anaerobic repeated tests | 20 ± 1 | Yes |

| Kaikkonen et al. (1998) | [57] | Ubiquinone + | 90 + Vit E | 21 d | Yes | 37/18 | Moderately trained subjects | Male | Marathon | Marathon | 40 ± 7 | No |

| Laaksonen et al. (1995) | [58] | Ubiquinone + | 120 + Omega 3 | 42 d | Yes | 11/11 | Well trained subjects | Male Male | Marathon & triathletes | Graded max. test | 28 (22–38) | No |

| 8/8 | 64 (60–74) | No | ||||||||||

| Leelarungrayub (2010) | [59] | Ubiquinone | 300 | 12 d | No | 16/16 | Moderately trained subjects | Male & Female | Swimmimg | Treadmill time to exhaustion & Swimmimg 100–800 m | 15 ± 1 | Yes 100 m, No 800 m |

| Malm et al. (1996) | [60] | Ubiquinone | 120 | 20 d | Yes | 15/9 | Moderately trained subjects | Male | - | Anaerobic tests | 20–34 | No |

| Malm et al. (1997) | [61] | Ubiquinone | 120 | 22 d | Yes | 18/9 | Moderately trained subjects | Male | - | Graded max and Anaerobic tests | 25 ± 3 | No |

| Mizuno et al. (2008) | [62] | Ubiquinone | 100 & 300 | 56 d | Yes | 17/17 | Physically active subjects | Male & Female | - | Anaerobic repeated tests under fatigue | 38 ± 10 | Yes |

| Nielsen et al. (1999) | [63] | Ubiquinone + | 100 + Vit E & Vit C | 42 d | Yes | 7/7 | Well trained subjects | Male | Triathletes | Graded max. & Local fatigue (31P-NMRS) | 22–32 | No |

| Reference | Change CoQ10 Total | Measured Parameters and Effects of CoQ10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μg/mL) | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μmol/mol Chol) | Muscle Pre ➝ Post (nmol/g Protein) | Inflammatory Pattern | Antioxidant Pattern | Physical Performance | Sport Performance | Muscle Injury | Other | |

| Drobnic et al. (2020) | Plasma ↑ Muscle ↑ | 1.11 ➝ 2.34 | 212 ➝ 476 | 245 ➝ 299nmol/g protein | IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MCP-1, TNFa ↓ | MDA ↓, TAC ↑ after exercise | Lactate and fatigue perception ↑, | |||

| Emami et al. (2018) | Plasma ↑ | ≃0.8 ➝ ≃2.5 | TAC ↑, LPO ↓, | LDH, CK-MB, Mb, Troponin I ↓ | ||||||

| Fiorella et al. (1991) | Plasma ↑ Thrombocites↑ | 0.6 ➝ 1.4 37.5➝61.8 | LA, UA, Ammonia ↔ | Running distance and time to exhaustion ↑, | CK, LDH ↓, | |||||

| García-Verazaluce et al. (2015) | - | IL6 ↓ | Costisol ↓ | |||||||

| Geiss et al. (2004) | Plasma ↑ | 0.6 ➝ 1.7 | Power output ↑ | |||||||

| Gökbel et al. (2010) | - | Peak Power ↔, Mean Power ↑, Fatigue Index ↔ | ||||||||

| Gökbel et al. (2016) | Plasma ↑ | 1.3 ➝ 3.0 | MDA ↓, GPX↓, SOD ↔, after exercise (NS) | |||||||

| Guerra et al. (1987) | Plasma ↑ | Ns | VO2max ↑ | Possible better race time | ||||||

| Gül et al. (2011) | - | MDA ↓, NO, XO, SOD, GPx ↔, UA ↑ | ||||||||

| Kaikkonen et al. (1998) | Plasma ↑ | 1.96 ➝ 2.03 | GSH, UA, LDLox, TRAP ↔ | |||||||

| Laaksonen et al. (1995) | Plasma ↑ Muscle ↑ | 0.9 ➝ 2.0 | 118 ➝ 128 nmol/g protein | MDA ↔ | VO2max ↔, Time to exhaustion | |||||

| Plasma ↑ Muscle ↔ | 1.31 ➝ 3.5 | 92 ➝ 78 nmol/g protein | ||||||||

| Leelarungrayub et al. (2010) | Plasma ↑ | 1.1 ➝ 2.3 | MDA, NO ↓, TAC, SOD ↔, GSH ↑ | Increase time to fatigue | No better 800 m swimming time | |||||

| Malm et al. (1996) | - | CK ↑ | ||||||||

| Malm et al. (1997) | - | ROS ↑ | VO2max ↔, Max power ↔ | |||||||

| Mizuno et al. (2008) | Plasma ↑ | 100 mg. 0.5 ➝ 2.0 300 mg. 0.5 ➝ 3.3 | Perception of fatigue ↓, Perception of recovery, Max velocity ↑ | |||||||

| Nielsen et al. (1999) | Plasma ↑ | 0.9 ➝ 1.8 | VO2max ↔ | Muscle metabolism ↔ | ||||||

| Reference | Molecule | CoQ10 mg/d | Duration (d: Days) | Placebo | n Total/CoQ10 | Type of Subjects | Sex | Sport/Activity | Exercise Testing | Age (Years) | Impact on Phys./Sport Perf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okudan et al. (2017) | [64] | Ubiquinone | 200 | 28 d | Yes | 21/11 | Non active | Male | - | Exccentric ex. | 23 ± 0 | No |

| Östman et al. (2012) | [65] | Ubiquinone | 90 | 56 d | Yes | 23/11 | Moderately trained subjects | Male | - | Various exercise capacity tests | 28 ± 9 | No |

| Porter et al. (1995) | [66] | Ubiquinone | 150 | 56 d | Yes | 13/6 | Physically active subjects | Male | Some with hypertension | Graded Max and Forearm Handgrip tests | 45 ± 2 | Yes |

| Snider et al. (1992) | [67] | Ubiquinone + | 100 + Vit E, C inosine, citochrome C | 28 d | Yes | 11/11 | High level | Male | Triathletes | Graded max. test | 25 ± 1 | No |

| Tauler et al. (2008) Ferrer et al. (2009) | [69,70] | Ubiquinone + | 100+ Multivitamin | 90 d | Yes | 19/8 | High level | Male | Soccer | Competition Match | 20 ± 0 | Yes |

| Vanfraechem et al. (1981) | [71] | Ubiquinone | 60 | 56 d | Yes | 6 | Non active | Male | None | Graded max. 4w–8w | 22 ± 2 | Yes |

| Wyss et al. (1990) | [73] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 30 d | Yes | 18/18 | Physically active subjects | Male | Running | Graded max. | 25 ± 4 | Yes |

| Yamabe et al. (1991) | [74] | Ubiquinone | 90 | 6 months | No | 9/9 | Non active with inabilities to do exercise | Male | - | Graded max. | 51 ± 5 | Yes |

| Ylikoski et al. (1997) | [75] | Ubiquinone | 90 | 42 d | Yes | 18/18 | High level | Male | cross-country skiers | Graded max. | Ns | Yes |

| Zeppilli et al. (1991) | [76] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 30 d | Yes | 9/9 | High level | Male | Volleyball | Graded max test | 17–2 | Yes |

| 10 | Non active | - | 23–29 | Yes | ||||||||

| 8 | Patients | Mit. Disease | 23–29 | Yes | ||||||||

| Zheng et al. (2008) | [77] | Ubiquinone | 30 | 1d | Yes | 11/11 | Non active | Male | - | Rest & Low intensity exercise (30% HRmax) | 26 ± 1 | Yes |

| Zhou et al. (2005) | [78] | Ubiquinone + | 150+ Vit E | 14 d | Yes | 6/6 | Physically active subjects | Male | - | Submaximal exercise and Graded max tests | 30 ± 7 | No |

| Zuliani et al. (1989) | [79] | Ubiquinone | 100 | 28 d | No | 12 | Non active | Male | - | 60’ ciloergometry | 26 | No |

| Sanchez-Cuesta et al. (2020) | [99] | . | - | 2 Sport seasons | - | 24 & 25 | High level | Male | Soccer | Weekly competition | 26 ± 4 | Yes |

| Reference | Change CoQ10 Total | Measured Parameters and Effects of CoQ10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μg/mL) | Plasma Pre ➝ Post (μmol/mol Chol) | Muscle Pre ➝ Post (nmol/g Protein) | Inflammatory Pattern | Antioxidant Pattern | Physical Performance | Sport Performance | Muscle Injury | Other | |

| Okudan et al. (2017) | Plasma ↑ | 1.0 ➝ 1.7 | MDA, SOD ↔ | CK, Myogb. ↔ | ||||||

| Östman et al. (2012) | - | MDA, UA, hypoxanthine ↔ | Exercise capacity, VO2max, Max power, Lactate ↔ | CK, UA ↔ | ||||||

| Porter et al. (1995) | Plasma ↑ | 0.7 ➝ 1.0 | VO2max ↔ LA ↓(NS) | Vigor perception ↑ | ||||||

| Snider et al. (1992) | - | Time to exhaustion, RPE ↔ | ||||||||

| Tauler et al. (2008) Ferrer et al. (2009) | Plasma ↑ | 3.0 ➝ 3.6 | SOD ↑, MDA ↓ | ↑ Time spend in active working zone (Z3-Z5) | ||||||

| Vanfraechem et al. (1981) | - | Maximal load and O2 consumption 170 w and max. | Cardiaovascular and cardiorespiratory parameters ↑ | |||||||

| Wyss et al. (1990) | Plasma ↑ | Ns | VO2max ↑, Max work ↑, | |||||||

| Yamabe et al. (1991) | - | VO2max, Max power and Anaerobic threshold ↑ | ||||||||

| Ylikoski et al. (1997) | Plasma ↑ | 0.8 ➝ 2.8 | VO2max, max power, Anaerobic threshold, and HRTime↑ | |||||||

| Zeppilli et al. (1991) | Plasma ↑ | 0.6 ➝ 1.3 Vb 0.7 ➝ 1.0 NA | VO2max, max power ↑ | |||||||

| Zheng et al. (2008) | - | VCO2/VO2 ↓, HR ↔ | ↑ Power HR variability | |||||||

| Zhou et al. (2005) | Plasma↑, Muscle ↔ | 0.8 ➝ 2.6 | 207 ➝ 220 (nmol/g protein) | VO2max ↔, HR ↔, RPE ↔, Anaerobic threshold ↔ | ||||||

| Zuliani et al. (1989) | Plasma ↑ | 0.5 ➝ 1.3 | Glucose, Insulin, LA ↔ | CK ↔, | Glycerol ↔, FFA ↓ | |||||

| Sanchez-Cuesta et al. (2020) | Plasma ↑ | Preseason 0.6 Middle season 0.9 | The highest values have better competition parameters | CK ↓ | Better Testosterone/cortisol pattern | |||||

| Physical Condition Categories | Number of Studies | CoQ10 Effect | Total | Sport Performance | Exercise Performance | Oxidative Pattern | Muscle INJURY | Inflammatory Pattern | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High level/Well trained athletes | 28 | Positive | 39 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| No effect | 12 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Moderate trained/Physically active | 20 | Positive | 11 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||

| No effect | 18 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 3 | ||||

| Negative | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Non active subjects | 9 | Positive | 11 | 6 | 1 | 4 | |||

| No effect | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Patients | 1 | Positive | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| TOTAL | 58 | number tests | 100 * | 3 | 40 | 25 | 14 | 7 | 11 |

| Positive | 63 | 2 | 23 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 10 | ||

| No effect | 34 | 1 | 17 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Negative | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Age Categories | Number of Studies | CoQ10 Effect | Total | Sport Performance | Exercise Performance | Oxidative Pattern | Muscle Injury | Inflammatory Pattern | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 37 | Positive | 38 | 2 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 8 |

| No effect | 26 | 1 | 13 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Negative | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| 31–50 | 11 | Positive | 15 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | |

| No effect | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| >50 | 7 | Positive | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| No effect | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| No specified | 3 | Positive | 3 | 3 |

| Physical activity: | Four types: No physically active or light activity (<3 d/week), Moderately active (3–5 d/week), Very active (5–7 d/week), High level athletes. |

| Age (years): | Four types: ≤33, 34–48, 49–64, ≥65 |

| Diet: | Homogenise the sample according to the type of diet |

| Dosage | 4.0–4.5 mg/kg/d of Ubiquinol or Ubiquinone with Phytosome or Ubiquinone with vehicle to increase bioavailability, or explaining perfectly the diet related to the administration. |

| Placebo | Yes, double blinded. |

| Type of study | Parallel, never crossover to avoid training and supplementation effect |

| Tissue concentration (plasma) | Mandatory. Always after 24 h after last doses of placebo or study substance. Recommended before and after exercise stress test. Determined always as “μmol/mol Chol” and added as “μg/mL”. |

| Tissue concentration (muscle) | Very recommended. Indispensable to know mitochondrial density. Determined as “nmol/g protein” |

| Treatment period | >1 week. |

| Effort test before and after supplementation | Characterization of the maximal oxygen consumption of every subject by a graded maximal exercise test. Evaluation of the metabolic efficiency under, at and upper the anaerobic threshold. Long duration exercise at a submaximal level to evaluate oxidative and inflammatory pattern. Evaluation of subjective fatigue perception |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drobnic, F.; Lizarraga, M.A.; Caballero-García, A.; Cordova, A. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Its Impact on Exercise and Sport Performance in Humans: A Recovery or a Performance-Enhancing Molecule? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091811

Drobnic F, Lizarraga MA, Caballero-García A, Cordova A. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Its Impact on Exercise and Sport Performance in Humans: A Recovery or a Performance-Enhancing Molecule? Nutrients. 2022; 14(9):1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091811

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrobnic, Franchek, Mª Antonia Lizarraga, Alberto Caballero-García, and Alfredo Cordova. 2022. "Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Its Impact on Exercise and Sport Performance in Humans: A Recovery or a Performance-Enhancing Molecule?" Nutrients 14, no. 9: 1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091811