1. Introduction

Planning in the medium-long term the construction of an integrated thermal and electrical energy production system fed by renewable sources (also known as hybrid renewable energy systems,

HRES) is certainly a tricky but interesting investment decision that occurs under multiple uncertainties. In recent years, in fact, the deregulation of the electricity sector, as well as the introduction of environmental constraints, has significantly stimulated the market of solutions for local energy production and consequently raised the attention of investors to new business opportunities, also adding new variables and constraints that further complicate the investment decision [

1]. As an example, one can cite the call for reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the new targets for penetration of renewable energy sources (

RES) in the electricity generating mix (Directive 2009/28/EC) and the Energy Performance of Buildings Directives (2010/31/EU and 2018/844/EU), which require new buildings to be nearly zero-energy by the end of 2020.

In this context, energy capacity planning and optimal power generation mix (or portfolio) are among the most challenging and investigated topics, both in a large-scale perspective, as for the national electricity generation system [

2], and for small-scale plants, as stand-alone configurations or autonomous buildings [

3,

4,

5]. Critical issues typically addressed are: the number of different energy sources to be included into the

HRES; the type of technology of the generation sub-systems (conventional or not); the design parameters of the

HRES (size, control, and management policies); the strategies used for decision assessment.

Many possible system configurations and uncertain variables should be considered in the problem formulation [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, the increased complexity of

HRES with respect to the systems fed by a single form of energy is due to the non-linear characteristics of the components, the high number of variables and parameters that have to be considered for the optimal design, and the fact that the ideal configuration and the optimal control strategy are interdependent [

11]. Modern

HRES are generally integrated (electrical, thermal components and buildings), made of highly-coupled subsystems where different technologies (e.g., renewable energy systems and traditional generators) cooperate for concurrent multiple objectives, such as reliability, cost efficiency, environmental sustainability, indoor comfort, and indoor air quality [

12]. This condition calls for a robust and more integrated approach to the evaluation of the best system design, able to deal with the increasing complexity of the decision context, an accurate but efficient dynamic modeling of components interconnections, and decision tools able to address the stakeholders towards the most efficient and cost-effective solutions [

13,

14,

15].

In [

11,

16,

17,

18] the authors presented a significant review of studies regarding stand-alone

HRES. Evidence shows a great variety of design, simulation, control and optimization approaches, as well as available software, such as HOMER (Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewables, HOMER Energy, Boulder, CO, USA), the most used tool for electric energy systems, developed by NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, USA). Indeed, concerning the design and simulation of

HRES, most of the works focus on the sole electricity generation, while many thermal aspects and the model of the building are often oversimplified or neglected. Faccio et al. Reference [

19] presented an interesting review of the most recent works on the optimal design of

HRES. The cost factor is the most common optimization goal, together with environmental emissions. Only in a few cases do the works aim to optimize the operation of a specific, most delicate component (e.g., the electric battery). In [

20], the authors reviewed the main methodologies used for the optimization, highlighting positive aspects and drawbacks of each modeling technique, such as linear programming, particle swarm optimization, Monte Carlo analyses, and hybrid techniques.

The large number of research works in this field shows that HRES are a topic of great interest, in particular because highly interacting energy systems cannot be analyzed by traditional design approaches. However, to the best of our knowledge, universal straightforward design procedures and decision criteria do not exist, as any specific project has peculiar characteristics, objectives and priorities set by the decision maker. The multi-objective optimal design requires the set-up of a multi-variable optimization problem with all the well-known drawbacks, such as computational effort, selection of the multi-objective method, optimization algorithms, physical interpretation, uncertainty and robustness of the resulting optimal configurations.

Recent reviews on optimization techniques applied in

HRES design [

21,

22,

23] present a general trend in analyzing, classifying and developing novel algorithms according to their ability to handle high-dimension variable spaces [

24]. On the contrary, there is a limited attention on the potential of the preliminary analysis of the design space, to determine which variables are the main drivers of system performances and consequentially reduce the dimension of the problem. The latter approach is well-known in the design-of-experiments technique with the name of “factors screening” [

25], in which the number of experiment variables (i.e., the factors) is limited for practical and economic reasons. A similar approach can be used in the multi-variable optimization problems [

26], to reduce the design space, use simpler optimization techniques, but preserving the quality of the final solution.

This work applies this approach to the multi-objective optimization of a HRES system, showing the advantages at the computational level, but also (and particularly) in terms of engineering understanding of the problem, interpretation of results, and support for the decision maker in the investment analysis and HRES planning. The work includes:

An integrated model for the simulation of the HRES and the building dynamics based on holistic and validated physical models to assess both thermal and electrical energy flows during the system lifetime, with low computational requirements. The strength of this approach is that, conversely to the aforementioned scientific literature, it considers the proper size and operation of each single component in the perspective of the global performance of the entire system, both for electrical and thermal aspects. The main drawback consists of the accuracy of the subsystem models, which must be coherent with the simulation time step and the uncertainty of the energy fluxes estimation;

A multi-objective optimization procedure that considers the targets of environmental sustainability together with the traditional financial performance of investments;

A screening methodology aimed at reducing the computational effort of the multi-objective algorithm. The optimization procedure is limited only to those variables with a high correlation (or “effect”) with the objective functions. The total computational effort of the variable identification and reduced optimization problem is very low with respect to the original problem. Together with the computational effort, a reduced optimization problem has the following advantages:

- ○

an easier interpretation of the optimal design(s) found by the optimization algorithm, such as operative features of the system and possible correlations among the optimal value of the main design variables;

- ○

the drawing of handy decision charts that can be used by the decision makers to assess the energy and economic performance of the design alternatives, helping the selection of the best configurations according to the specific objectives and priorities;

- ○

a simpler sensitivity analysis to investigate the robustness of the optimal solutions identified by the sizing procedure.

The presented case study is representative of an autonomous small-to-medium accommodation building (off-grid, both electricity and gas) in mild-Mediterranean climates; anyway, the proposed approach is generic enough to be applied also to any energy system optimization, both for stand-alone and on-grid building-integrated HRES.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the reference

HRES system and the energy and economy modelling methods.

Section 3 illustrates the reduction methodology based on a random sample correlation analysis. The results, the post-processing analysis, and the related discussion are presented in

Section 4.

Section 5 presents the sensitivity analysis, and conclusions are finally provided in

Section 6.

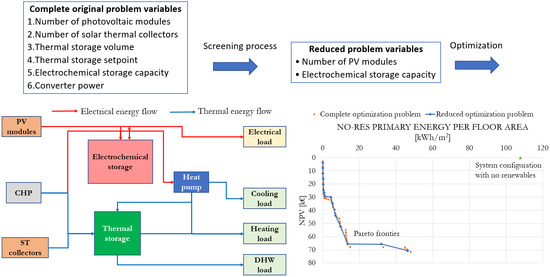

2. Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems (HRES) Energy and Economy Modelling

In this work, we refer to the optimal design of an off-grid building served by a

HRES system, according to cost-benefit considerations. The reference facility is an off-grid small-to-medium accommodation building, located in an isolated area of the countryside in a mild-Mediterranean region. Energy requirements include heating, cooling, domestic hot water (

DHW), and electrical services. To address these loads, an integrated system including solar thermal panels, photovoltaic modules, thermal storage (

TS), electrochemical storage (

ES), a heat pump (

HP), and a combined heat and power system (

CHP) must be optimally designed. A schematic representation of the overall system is presented in

Figure 1.

As the building is a stand-alone one, particular attention should be given in the design of the overall

HRES system, as all the technologies have to be designed and integrated to address the building requirements, without oversizing, so avoiding additional costs and, in some cases, also worse operating performances (e.g., heat pumps). The overall building and energy system are analyzed through an hourly dynamic simulation, using literature or in-house mathematical models shortly discussed in

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3 and

Section 2.4.

2.1. External Climate and Building Envelope Model

The hourly heating and cooling loads,

and

, are evaluated correlating the design thermal load and a mean external temperature

on the effective time shift of the building [

27,

28]. For the summer season, the mean sol-air temperature [

28,

29] on the same time shift of the building,

, is considered, instead of the external temperature. The two equations read:

Typical hotel schedules are used as

DHW and electrical load profiles, including induction cooking, lighting, and household appliances [

30]. Further details about the characterization of the energy requirements profiles can be found in [

31].

2.2. Modeling of the Generation System

The performance of the photovoltaic (

PV) modules are evaluated through the assessment of the cell temperature, depending on the clearness of the sky

[

32] and the external temperature,

, using the model discussed in [

33]. The equations read:

As for the evaluation of the solar thermal system (

ST) panels’ efficiency, classical models in literature and technical standards are used [

32,

34]. The Equations read:

where

is assumed equal to the water temperature in the thermal storage (see Equation (5)).

The heat pump is a pivotal element in the system, as it links thermal and electrical energy fluxes. It can receive electrical energy from the

PV modules, the

CHP generator, or the electrochemical storage and provide energy to: (i) the cooling service directly to the building; (ii) for the heating service, either directly to the building or through the thermal storage, and (iii) for the

DHW service, heating the thermal storage. On the contrary, the

ST collectors can only provide thermal energy to the thermal storage. The heat pump performances are evaluated through the second-law efficiency method [

35], using a fixed value of both

and

(assessed through manufacturers’ data), the outdoor temperature,

, and the supply water temperature

/

for the evaluation of the ideal

COP/EER. The equations read:

The CHP consists of a diesel-engine generator. When necessary, it recharges the electrochemical storage to the assumed minimum state of charge and/or delivers the electrical load that cannot be provided by the ES due to the power limits of the converter. Fixed values for the electrical power generation efficiency, , and thermal power recovery efficiency,, are used.

2.3. Modeling of the Thermal Storage

A simplified lumped-element thermal storage model is considered to evaluate the

evolution considering heat inputs (thermal energy from the

CHP, solar thermal collectors, heat pump, and recovered energy from

PV overproduction), heat outputs (energy used for heating and

DHW services), thermal losses, and the variation of internal energy. The equations read:

The thermal storage is kept at a temperature equal or higher than the set-point temperature by the thermal generators. When its temperature is higher than the threshold value , the heat pump is switched-off from direct heating mode and the heating service is provided by the thermal storage.

2.4. Modeling of the Electrochemical Storage

During standard plant operation, the electrochemical storage receives the surplus of the energy produced by the PV systems and/or delivers the load deficit that cannot be met by the PV. Lithium technology has been taken as reference. In fact, despite the relative high costs with respect to less expensive technologies (i.e., lead-acid batteries, etc.), in the last few years lithium batteries have been considered increasingly also for stationary applications, for their better performance in cycle-life. In fact, being able to sustain from tens up to hundreds of charging-discharging cycles, they can require a very short number (or none) of substitutions during the useful life of the considered application, thus becoming preferable to the previous technologies.

The operative state of charge is assumed to be between the 10% and the 90% of the nominal energy,

. About storage losses, a constant round trip efficiency,

, is supposed, as usual in literature. The state of charge

, i.e., the ratio between the charge stored inside and the battery capacity (extractable charge) at a reference current and temperature, is evaluated at any time step as follows:

Possible overloads are assumed to be dissipated, while the CHP unit provides the electrical energy to keep the at least at at any time. Besides, the CHP meets the remaining electrical load when the demand is higher than the maximum capacity of the converter.

With regard to the storage lifetime, it must be carefully verified if the considered usage of electrochemical storage at many charging-discharging cycles could rise concerns about its life. Thus, considering experimental data reported in literature [

36,

37,

38] and from manufacturers’ indications [

39], and focusing the attention, as said, on lithium technology, an electrochemical storage subject to such solicitation can follow the behavior as depicted in

Figure 2. Different typologies are typically available in the general category of lithium batteries, depending on the electrode typology (e.g.,

LFP, lithium iron phosphate,

NMC, nickel manganese cobalt, etc.). From the presented test data, the average trend, calculated as arithmetic mean of the different allowed charging-discharging cycles at the same abscissa, has also been reported in

Figure 2, in orange color. As shown, in the case of shallow charging-discharging cycles, battery life expectation can reach hundreds of thousands of micro-cycles, while just few thousands are sustainable when extended depth of discharge is considered. These results have been used to evaluate the battery allowed number of cycles, in order to finalize the economy analysis in

Section 2.5. In particular, the black curve of the “worst” case among the examined technologies has been considered as precautionary measure. The latter curve has been discretized in a five-step piecewise function as shown in

Table 1.

The number of cycles in each bin is evaluated according to the depth of discharge (

DOD), i.e., the ratio between the extracted charge and the battery capacity (extractable charge) at a reference current and temperature, of each charging–discharging cycle occurring during the system lifetime. Due the reduced power typically delivered in building systems (see

Section 4.2), C-rate, i.e., the amplitude of the current solicitation, expressed as multiples of the battery capacity, and temperature are assumed to stay around their nominal values. Therefore, for simplicity, dependency from C-rate and temperature was not included in Equation (7), which only considers

DOD. For instance, the counter

is the number of cycles with a relative depth of discharge

between 0.9 and 0.74,

is the number of cycles with a relative depth of discharge

between 0.74 and 0.58, and so on. The cumulative damage of the

ES at the

t-th time step is evaluated through Equation (7). When

, the electrochemical storage is substituted and all the counters are reset to zero.

2.5. Economic Analysis

The net present value (

NPV) is assumed as the main economic indicator. For the

j-th system configuration, the

NPV is calculated comparing the actual cash flow with the option of not investing in a

HRES, but using a

CHP to meet both electrical and thermal energy demands (i.e.,

No-RES or no renewable energy sources configuration).

The total cost at the t-th year, , is given by the total initial installation cost, , the operation and maintenance () costs, (which includes the fuel costs), the replacement cost of the devices that have exhausted their operational life, , the positive cash flows due to the possible residual value, , of the components after the whole system lifetime. In other words, the Boolean variable in Equation (9) is equal to 1 only in the N-th year.

The initial cost for the

j-th configuration is given by the sum of the installation cost of each component, namely:

where

,

,

,

,

are the unitary costs of the photovoltaic modules, solar thermal collectors, thermal storage, electrochemical storage, and electrochemical storage converter, respectively. The heat pump capacity is assumed as constant for all the tested configuration as its value only depends on the heating and cooling design load of the building. The

CHP sizing and installation cost depends on the maximum electrical power output required in the

j-th configuration during the year and it is thus related to the number of

PV modules and the electrochemical storage and converter capacities. However, a minimum back-up power of 2.5 kW

el is always installed, namely:

The operation and maintenance costs are distinguished into variable costs, proportional to the energy use (i.e., the

CHP fuel costs) and fixed costs, which include annual assurance costs, programmed maintenance, etc. The latter is assumed proportional to the

PV capacity, so the yearly

cost is equal to:

The replacement cost,

, is the present value of the initial installation cost of the replaced sub-system. The main assumption under this hypothesis is that the adopted technologies are similar over the years, so they only experience a price variation in line with the assumed inflation rate, but they do not change their performance or operational duration. In this study, the electrochemical storage and the

CHP generator are the only components that need to be replaced during the

HRES lifetime. The replacement years for both subsystems are evaluated according to Equation (14), thus accounting for the simulated operational conditions and time.

where:

The residual value,

, refers to the possible value of the electrochemical storage and

CHP unit at the end of the

HRES lifetime, therefore it contributes to the total cost only in the

N-th year. We consider a second-hand value of the two devices only if the last replacement respectively occurs in the last 10 and 5 years of the system lifetime. In other words, if the last replacement occurs in the

t-th year, we have:

where:

The other economic parameter is the internal rate of return, , namely the discount rate that makes the net present value equal to zero at the end of the system lifetime.

5. Sensitivity Analysis to the Unitary Price of the Electrochemical Storage

In this Section, we perform a sensitivity analysis of the Pareto frontier as a function of the unitary price of the electrochemical storage. The latter parameter is the most uncertain one, as it depends on the considered

ES technology and unclear cost evolution. In

Section 4.2, we showed that the electrochemical storage is the most relevant variables for economy performance. Finally, in

Section 4.2, we observed a great dissipation of the electrical energy; therefore, it is interesting to understand whether a cheaper price would allow the installation of higher storage capacities, potentially reducing the aforementioned electrical overproduction.

As said, different lithium-based technologies are today available: as example, lithium iron phosphate (

LFP) batteries are quite cheap, and their price can be assumed, from the authors’ experience [

43] and market data [

44,

45], at about 300 €/kWh. On the other hand, nickel manganese cobalt (

NMC) ones are much more expensive, at about 600 €/kWh. From predictions today available, these costs will probably further decrease. In this way, it is possible to predict one levelling in the range 300–400 €/kWh in the next years.

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show the correlation coefficient for

and

depending on four different

. The reduced prices do not change the relevance ranking of the variables; thus, the reduced two-variable optimization problem still applies.

Figure 18 shows the four different Pareto frontiers: a lower

introduces many other configurations close to the null value of the

No-RES energy consumption. In other words, many high-efficiency configurations have become economically viable due to a lower initial investment.

Table 6 shows the distribution of the two main design variables,

and

, as a function of the electrochemical storage price. As mentioned above, a lower

moves the distribution towards higher values of both

PV modules and electrochemical storage size.

The

ES unitary price does not affect much the optimal range of the ratio between the nominal electrochemical storage capacity and the

PV capacity (see

Figure 19). Only the lowest price scenario,

, makes the installation of larger

ES viable. However, the general criterion of 4–8 h seems a robust guideline.

Figure 20 shows that the electrical overproduction does not reduce with lower

, as the more favorable economic context increases the size of the electrochemical storage, but also increases the number of

PV modules.

Figure 21 shows the median value of the

of the configurations on the Pareto frontier, as a function of the

ES unitary price. We observe that the notable amount of installed

PV reduces the deficit of electrical energy (Equation (6d)), resulting in low values of

and high values of

. The latter operative condition also ensures the lifetime of the electrochemical storage, which is never replaced during the 20 years considered.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we optimized a HRES system serving a reference off-grid small-to-medium accommodation facility, according to a multi-objective perspective: the minimization of No-RES energy consumption and maximization of NPV at the end of system lifetime. After describing both energy and economic models, we showed how the multi-variable optimization problem can be simplified through a correlation analysis of a random sample of possible configurations, to identify the design variables that mainly affect the objective functions.

The methodology has been applied to a test case including air-to-water heat pumps, a combined heat-power generator, photovoltaic modules, solar thermal collectors, and electrochemical and thermal storages. The design variables have been reduced from 6 to 2 (i.e., PV number and nominal energy of the electrochemical storage) and the design alternatives from 330,000 to 220. We showed how the reduced problem does not exclude optimal configurations, since the new Pareto frontier overlaps that obtained considering all the 6 variables.

Achievable energy savings go from ~57% to ~100%, and the corresponding NPV and IRR after 20 years of operation go from ~4 k€ to ~70 k€ and from 5.2% to ~27%. Finally, we found a simple rule of thumb to design PV capacity and ES size for similar PV-driven off-grid buildings: the best ratio between the two quantities goes from 4 to 8 h, regardless the cost of the electrochemical storage. A lower price makes economically viable configurations with higher PV capacity and ES size, thus reducing the use of No-RES generators. However, the electrical overproduction is not reduced, as the optimal ratio between PV capacity and electrical storage capacity does not vary.

Next studies will concern a more detailed stochastic analysis of both technical and economic parameters, to figure out the probability distributions of the selected objective functions and thus the statistically expected performances and the worst-case scenarios, for risk-management purposes.