A Qualitative Content Analysis of Rural and Urban School Students’ Menstruation-Related Questions in Bangladesh

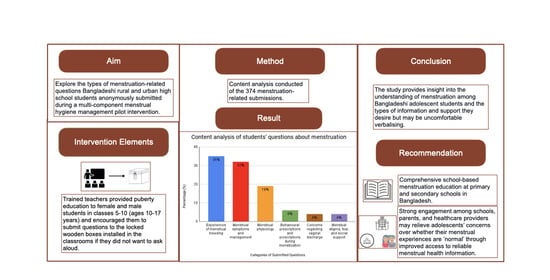

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Description of the ‘Question Box’ Intervention Component

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiences of Menstrual Bleeding

3.1.1. Timing of Menstruation

3.1.2. Menstrual Blood Flow

3.1.3. Requests for Menstrual Hygiene Management Advice

3.2. Menstrual Symptoms and Management

3.3. Menstrual Physiology

3.4. Behavioural Prescriptions and Proscriptions during Menstruation

3.5. Concerns Regarding Vaginal Discharge

3.6. Menstrual Stigma, Fear, and Social Support

I think this is a problem for many girls. If we tell the adults, they do not want to listen. They don’t give us any appropriate answer. Many of us suffer from mental health issues due to this and it harms us. Please provide us with a way to come out of this mental suffering.—Student in Class VII, urban school

3.7. Cross-Cutting Themes

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Ethical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ibitoye, M.; Choi, C.; Tai, H.; Lee, G.; Sommer, M. Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rembeck, G.I.; Möller, M.; Gunnarsson, R.K. Attitudes and feelings towards menstruation and womanhood in girls at menarche. Acta Paediatr. 2006, 95, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, M. Ideologies of sexuality, menstruation and risk: Girls’ experiences of puberty and schooling in northern Tanzania. Cult. Health Sex. 2009, 11, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, K.; Curry, C.; Sherry; Ferfolja, T.; Parry, K.; Smith, C.; Hyman, M.; Armour, M. Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Programme Division/WASH: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Guidance for Monitoring Menstrual Health and Hygiene; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Patel, S.V. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.M. Adolescents’ Reproductive Health in Rural Bangladesh: The Impact of Early Childhood Nutritional Anthropometry; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, A.M.; Hutter, I.; van Ginneken, J.K. Perceptions of adolescents and their mothers on reproductive and sexual development in Matlab, Bangladesh. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2008, 20, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, N.S.; Khatun, R.; Akter Halim, K.M.; Islam, S.; Muhammad, F. Assessment of knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among the female nursing students in a selected private nursing college in Dhaka City. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paria, B.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Das, S. A comparative study on menstrual hygiene among urban and rural adolescent girls of west bengal. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2014, 3, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, B.; Balkan, C.; Gunay, T.; Onag, A.; Egemen, A. Effects of different socioeconomic conditions on menarche in Turkish female students. Early Hum. Dev. 2004, 76, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan International. Break the Barriers: Girls’ Experiences of Menstruation in the UK Report; Plan International UK: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hennegan, J. Interventions to Improve Menstrual Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Do We Know What Works? In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies; Bobel, C., Winkler, I.T., Fahs, B., Hasson, K.A., Kissling, E.A., Roberts, T.-A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 637–652. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, L.; Nyothach, E.; Alexander, K.; Odhiambo, F.O.; Eleveld, A.; Vulule, J.; Rheingans, R.; Laserson, K.F.; Mohammed, A.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. ‘We keep it secret so no one should know’–A qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural Western Kenya. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Ackatia-Armah, N.; Connolly, S.; Smiles, D. A comparison of the menstruation and education experiences of girls in Tanzania, Ghana, Cambodia and Ethiopia. Compare 2015, 45, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Nabwera, H.; Sonko, B.; Bajo, F.; Faal, F.; Saidykhan, M.; Jallow, Y.; Keita, O.; Schmidt, W.P.; Torondel, B. Effects of Menstrual Health and Hygiene on School Absenteeism and Drop-Out among Adolescent Girls in Rural Gambia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, S.; Mahon, T.; Cavill, S. Menstrual hygiene matters: A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. Reprod. Health Matters 2013, 21, 257–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sumpter, C.; Torondel, B. A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennegan, J.; Dolan, C.; Steinfield, L.; Montgomery, P. A qualitative understanding of the effects of reusable sanitary pads and puberty education: Implications for future research and practice. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Baker, K.K.; Dutta, A.; Swain, T.; Sahoo, S.; Das, B.S.; Panda, B.; Nayak, A.; Bara, M.; Bilung, B.; et al. Menstrual Hygiene Practices, WASH Access and the Risk of Urogenital Infection in Women from Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torondel, B.; Sinha, S.; Mohanty, J.R.; Swain, T.; Sahoo, P.; Panda, B.; Nayak, A.; Bara, M.; Bilung, B.; Cumming, O.; et al. Association between unhygienic menstrual management practices and prevalence of lower reproductive tract infections: A hospital-based cross-sectional study in Odisha, India. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademas, A.; Adane, M.; Sisay, T.; Kloos, H.; Eneyew, B.; Keleb, A.; Lingerew, M.; Derso, A.; Alemu, K. Does menstrual hygiene management and water, sanitation, and hygiene predict reproductive tract infections among reproductive women in urban areas in Ethiopia? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoowalla, H.; Keppler, H.; Asanti, D.; Xie, X.; Negassa, A.; Benfield, N.; Rulisa, S.; Nathan, L.M. The impact of menstrual hygiene management on adolescent health: The effect of Go! pads on rate of urinary tract infection in adolescent females in Kibogora, Rwanda. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 148, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennegan, J.; Montgomery, P. Do Menstrual Hygiene Management Interventions Improve Education and Psychosocial Outcomes for Women and Girls in Low and Middle Income Countries? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, A.M.; Sivakami, M.; Thakkar, M.B.; Bauman, A.; Laserson, K.F.; Coates, S.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.U.; Sultana, F.; Hunter, E.C.; Winch, P.J.; Unicomb, L.; Sarker, S.; Mahfuz, M.T.; Al-Masud, A.; Rahman, M.; Luby, S.P. Evaluation of a menstrual hygiene intervention in urban and rural schools in Bangladesh: A pilot study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfuz, M.T.; Sultana, F.; Hunter, E.C.; Jahan, F.; Akand, F.; Khan, S.; Mobashhara, M.; Rahman, M.; Alam, M.U.; Unicomb, L.; et al. Teachers’ perspective on implementation of menstrual hygiene management and puberty education in a pilot study in Bangladeshi schools. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1955492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, S.Y.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Confusing categories and themes. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative content analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.U.; Luby, S.P.; Halder, A.K.; Islam, K.; Opel, A.; Shoab, A.K.; Ghosh, P.K.; Rahman, M.; Mahon, T.; Unicomb, L. Menstrual hygiene management among Bangladeshi adolescent schoolgirls and risk factors affecting school absence: Results from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.K. Breaking the silence: Menstrual hygiene in Bangladesh. The Daily Star, 4 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Types of Questions. Growing & Developing Healthy Relationships (GHDR). Available online: https://gdhr.wa.gov.au/guides/what-to-teach/question-box/types-of-questions (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Samandari, G.; Sarker, B.K.; Grant, C.; Huq, N.L.; Talukder, A.; Mahfuz, S.N.; Brent, L.; Nitu, S.N.A.; Aziz, H.; Gullo, S. Understanding individual, family and community perspectives on delaying early birth among adolescent girls: Findings from a formative evaluation in rural Bangladesh. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 8, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papreen, N.; Sharma, A.; Sabin, K.; Begum, L.; Ahsan, S.K.; Baqui, A.H. Living with infertility: Experiences among Urban slum populations in Bangladesh. Reprod. Health Matters 2000, 8, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, A.; Ahmed, S. Perspectives of Women about Their Own Illness; Number 16; ICDDR, B: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, S.F. Indigenous notions of the workings of the body: Conflicts and dilemmas with Norplant use in rural Bangladesh. Qual. Health Res. 2001, 11, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miiro, G.; Rutakumwa, R.; Nakiyingi-Miiro, J.; Nakuya, K.; Musoke, S.; Namakula, J.; Francis, S.; Torondel, B.; Gibson, L.J.; Ross, D.A.; et al. Menstrual health and school absenteeism among adolescent girls in Uganda (MENISCUS): A feasibility study. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillitteri, S.P. School Menstrual Hygiene Management in Malawi: More than Toilets; WaterAid: Cranfield, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Warrington, S.; Coultas, M.; Das, M.; Nur, E. “The door has opened": Moving forward with menstrual health programming in Bangladesh. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2021, 14, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, E.R.; Clasen, T.; Dasmohapatra, M.; Caruso, B.A. ‘It’s like a burden on the head’: Redefining adequate menstrual hygiene management throughout women’s varied life stages in Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbury, E. Needs Assessment RITU: Promoting Menstrual Health Management in Bangladesh; Simavi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.; Basnet, M.; Bhatta, A.; Khimbanjar, S.; Joshi, D.; Baral, S. Menstrual Hygiene Management in Udaypur and Sindhuli Districts of Nepal; WaterAid: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, S.E.; Rahman, M.; Itsuko, K.; Mutahara, M.; Sakisaka, K. The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: An intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. Bangladesh. Med. J. Open 2014, 4, e004607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.S.; Alliratnam, A.; Shankar, R. Menstrual problems and hygiene among rural adolescent girls of Tamil Nadu—A cross sectional study. Indian J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 2016, 3, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Shom, E.R.; Khatun, F. Menstrual hygiene practice between rural and urban high school adolescent girls in Bangladesh. Int. J. Reprod Contracept. Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 9, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simavi. Ritu Programme Final Report: Improving Menstrual Health of Girls in Bangladesh; Simavi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thakre, S.B.; Thakre, S.S.; Ughade, S.; Thakre, A.D. Urban-rural differences in menstrual problems and practices of girl students in Nagpur, India. Indian Pediatr. 2012, 49, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhasi, V.R.; Mahesh, V.; Manjunath, T.L.; Muninarayana, C.; Latha, K.; Ravishankar, S. A comparative cross sectional study of knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in rural and urban schools of Rural Karnataka. Indian J. Forensic Community Med. 2016, 3, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, J.; Patel, R. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls: A cross sectional study in urban community of Gandhinagar. J. Med. Res. 2015, 1, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainul, S.; Ehsan, I.; Tanjeen, T.; Reichenbach, L. Adolescent Friendly Health Corners (AFHCs) in Selected Government Health Facilities in Bangladesh: An Early Qualitative Assessment; Population Council, The Evidence Project: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nahar, Q.T.C.; Houvras, I.; Gazi, R.; Reza, M.; Huq, N.L.; Khuda, B. Reproductive Health Needs of Adolescents in Bangladesh: A Study Report; ICDDR, B, Centre for Health and Population Research: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). National Hygiene Survey 2018; Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, WaterAid Bangladesh, UNICEF Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Costos, D.; Ackerman, R.; Paradis, L. Recollections of Menarche: Communication between Mothers and Daughters Regarding Menstruation. Sex Roles 2002, 46, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooki, Z.; Shariati, M.; Chaman, R.; Khosravi, A.; Effatpanah, M.; Keramat, A. The Role of Mother in Informing Girls About Puberty: A Meta-Analysis Study. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2016, 5, e30360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundi, M.; Subramanyam, M.A. Menstrual health communication among Indian adolescents: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suma, K.G. Education and Behavioural Barriers for Menstrual Health Communication between Parent and Adolescent Girls. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Multidiscip. Phys. Sci. 2021, 9, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GDHR Portal Question Box: Growing & Developing Health Relationships (GDHR). Available online: https://gdhr.wa.gov.au/-/question-box (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Rabinowicz, R. Teaching Puberty: You Can Do It! Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2006, 15, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Teaching Sexual Health Instructional Methods. Available online: https://teachingsexualhealth.ca/teachers/sexual-health-education/understanding-your-role/get-prepared/instructional-methods/ (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Primary Education. The Real Period Project. Available online: https://www.realperiodproject.org/educators/primary/ (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Kazembe, A. Question box: A tool for gathering information about HIV and AIDS. Afr. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2010, 4, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Reeuwijk, M.; Nahar, P. The importance of a positive approach to sexuality in sexual health programmes for unmarried adolescents in Bangladesh. Reprod. Health Matters 2013, 21, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.M.; Fein, J.A. Adolescent decisional autonomy regarding participation in an emergency department youth violence interview. Am. J. Bioeth. 2005, 5, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konza, D.M. Researching in schools: Ethical issues. Int. J. Humanit. 2012, 9, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzmann, H. Ethical Issues in School-Based Research. Res. Ethics. 2009, 5, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouna, S.; Hamsa, L.; Ranganath, T.S.; Vishwanath, N. Assessment of knowledge and health care seeking behaviour for menstrual health among adolescent school girls in urban slums of Bengaluru: A cross sectional study. Int J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 4881–4886. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Health Education (BHE). School Health Program. Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Available online: http://bhe.dghs.gov.bd/ (accessed on 9 March 2022).

| Category/Sub-Categories | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total N | Percentage (%) | |

| Experiences of menstrual bleeding | 132 | 35 |

| Timing of menstruation | 100 | 26 |

| Menstrual blood flow | 14 | 4 |

| Request for menstrual hygiene management advice | 18 | 5 |

| Menstrual symptoms and management | 122 | 32 |

| Menstrual physiology | 70 | 19 |

| Behavioural prescriptions and proscriptions during menstruation | 22 | 6 |

| Concerns regarding vaginal discharge | 14 | 4 |

| Menstrual stigma, fear, and social support | 15 | 4 |

| Category/Sub-Categories | Urban | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class Level | ||||||

| Class 5 | Class 6 | Class 7 | Class 8 | Class 9 | Class 10 | |

| Experiences of menstrual bleeding | 6 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 21 | 2 |

| Timing of menstruation | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 2 |

| Menstrual blood flow | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Request for menstrual hygiene management advice | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Menstrual symptoms and management | 1 | 2 | 6 | 18 | 5 | 4 |

| Menstrual physiology | 2 | 5 | 2 | 15 | 12 | 4 |

| Behavioural prescriptions and proscriptions during menstruation | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Concerns regarding vaginal discharge | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Menstrual stigma, fear, and social support | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Category/sub-categories | Rural | |||||

| Class level | ||||||

| Class 5 | Class 6 | Class 7 | Class 8 | Class 9 | Class 10 | |

| Experiences of menstrual bleeding | 0 | 0 | 35 | 31 | 8 | 0 |

| Timing of menstruation | 0 | 0 | 31 | 25 | 6 | 0 |

| Menstrual blood flow | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Request for menstrual hygiene management advice | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Menstrual symptoms and management | 0 | 0 | 39 | 39 | 8 | 0 |

| Menstrual physiology | 0 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 6 (Class 9), 3 (Class 9–10) *, 1 (Class 10) | |

| Behavioural prescriptions and proscriptions during menstruation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 (Class 9–10) * | |

| Concerns regarding vaginal discharge | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Menstrual stigma, fear, and social support | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Category/Sub-Category | Examples of Questions Asked |

|---|---|

| Experiences of menstrual bleeding: Timing of menstruation | My age is 13 years but why hasn’t my period started? Will my irregular period become normalised or regular when I reach 15 years of age? Why is my period lasting for more than seven days? Period occurs twice in a year but lasts for 30 days, is it okay? Is it a health problem if girls have periods every 3–4 months, and will it be a problem for them to conceive? |

| Experiences of menstrual bleeding: Menstrual blood flow | Is there any harm in low bleeding during menstruation? What to do if there is excess blood? Why is there excessive bleeding a lot of times? Why do girls have blood clots or watery bleeding during periods? |

| Experiences of menstrual bleeding: Requests for menstrual hygiene management advice | Is it better to use a cloth or sanitary pads? If we use a cloth, how many days after should we change it? We want to know how we can maintain cleanliness while using cloth during periods. What do I do if I have menstruation in class and stain my clothes (school uniform)? How frequently should we change the cloths or pads during periods? The water supply in our washroom is not good and the washroom is dirty. |

| Menstrual symptoms and management | Why do girls have abdomen cramps during menstruation? How can we decrease cramps during periods? Why can’t we take medication to reduce abdominal cramps during menstruation? Why do I have acne during menstruation? Why do you have back pain during menstruation? |

| Menstrual physiology | What is menstruation and what is the reason for it? Why does menstruation take place? What happens when you are menstruating? Why can’t girls get pregnant without menstruation? What would happen if menstruation didn’t occur? If girls don’t menstruate are there any problems? |

| Behavioural prescriptions and proscriptions during menstruation | Why abstain from sex during menstruation? Why should we be cautious during menstruation? Why aren’t you allowed to eat sour foods during menstruation? Why don’t our father and mother let us go outside during menstruation? How should we conduct ourselves during menstruation? |

| Concerns regarding vaginal discharge | Why do girls have white discharge? What is the white substance that girls have? Why does white discharge occur? How long does it last and at what age does it start? What causes excessive white discharge? Is it genetic? What is the cure for this disease? Is there any problem if there is more white discharge? What to do if there is excess of it? |

| Menstrual stigma, fear, and social support | I am very scared about menstruation, what can I do to get out of this fear? Menstruation occurs in all girls but still why do girls laugh at menstruation? We talk about these issues with our older sisters, so I think we need to inform our mother about these issues. Can we tell our brother about menstruation? We need a madam (female teacher) for the subject of physical (puberty and sex) education. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehjabeen, D.; Hunter, E.C.; Mahfuz, M.T.; Mobashara, M.; Rahman, M.; Sultana, F. A Qualitative Content Analysis of Rural and Urban School Students’ Menstruation-Related Questions in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610140

Mehjabeen D, Hunter EC, Mahfuz MT, Mobashara M, Rahman M, Sultana F. A Qualitative Content Analysis of Rural and Urban School Students’ Menstruation-Related Questions in Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610140

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehjabeen, Deena, Erin C. Hunter, Mehjabin Tishan Mahfuz, Moshammot Mobashara, Mahbubur Rahman, and Farhana Sultana. 2022. "A Qualitative Content Analysis of Rural and Urban School Students’ Menstruation-Related Questions in Bangladesh" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610140