CaMKII Splice Variants in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: The Next Step or Redundancy?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

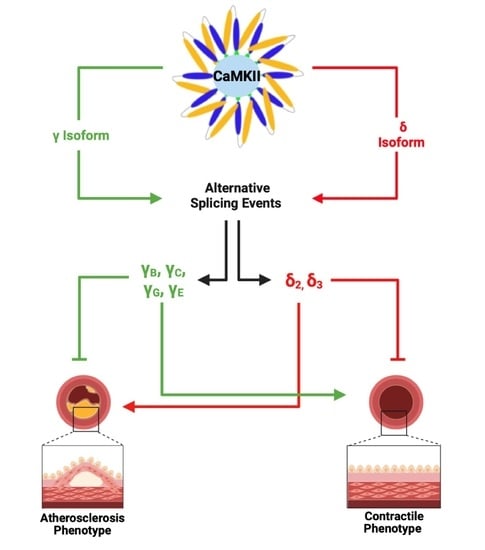

2. Structure, Activation and Diversity of CaMKII Gene Products

3. Splicing Events in CaMKIIδ and γ Isoforms

4. The Role of CaMKII in VSMC Migration

5. Reciprocal Expression of CaMKII Isoforms in VSMC Phenotypic Switching

6. Regulation of CaMKIIγ and CaMKIIδ in VSMCs

7. Role of CaMKII in VSMC Hypertrophy

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toussaint, F.; Charbel, C.; Allen, B.G.; Ledoux, J. Vascular CaMKII: Heart and brain in your arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2016, 311, C462–C478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- House, S.J.; Ginnan, R.G.; Armstrong, S.E.; Singer, H.A. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-delta isoform regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2007, 292, C2276–C2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- House, S.J.; Singer, H.A. CaMKII-delta isoform regulation of neointima formation after vascular injury. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Li, H.; Sanders, P.N.; Mohler, P.J.; Backs, J.; Olson, E.N.; Anderson, M.E.; Grumbach, I.M. The multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II delta (CaMKIIdelta) controls neointima formation after carotid ligation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through cell cycle regulation by p21. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 7990–7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, I.; Je, H.D.; Gallant, C.; Zhan, Q.; Riper, D.V.; Badwey, J.A.; Singer, H.A.; Morgan, K.G. Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent activation of contractility in ferret aorta. J. Physiol. 2000, 526 Pt 2, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, H.A. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II function in vascular remodelling. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, H.A.; Benscoter, H.A.; Schworer, C.M. Novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma-subunit variants expressed in vascular smooth muscle, brain, and cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 9393–9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schworer, C.M.; Rothblum, L.I.; Thekkumkara, T.J.; Singer, H.A. Identification of novel isoforms of the delta subunit of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Differential expression in rat brain and aorta. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 14443–14449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.K.; Erondu, N.E.; Kennedy, M.B. Purification and characterization of a calmodulin-dependent protein kinase that is highly concentrated in brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 12735–12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lautermilch, N.J.; Watari, H.; Westenbroek, R.E.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Modulation of CaV2.1 channels by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II bound to the C-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.R.; Kapiloff, M.S.; Durgerian, S.; Tatemoto, K.; Russo, A.F.; Hanson, P.; Schulman, H.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Molecular cloning of a brain-specific calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 5962–5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marganski, W.A.; Gangopadhyay, S.S.; Je, H.D.; Gallant, C.; Morgan, K.G. Targeting of a novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is essential for extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated signaling in differentiated smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hudmon, A.; Schulman, H. Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 2002, 364 Pt 3, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombes, R.M.; Faison, M.O.; Turbeville, J.M. Organization and evolution of multifunctional Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase genes. Gene 2003, 322, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, T.R.; Kolodziej, S.J.; Wang, D.; Kobayashi, R.; Koomen, J.M.; Stoops, J.K.; Waxham, M.N. Comparative analyses of the three-dimensional structures and enzymatic properties of alpha, beta, gamma and delta isoforms of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 12484–12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gangopadhyay, S.S.; Barber, A.L.; Gallant, C.; Grabarek, Z.; Smith, J.L.; Morgan, K.G. Differential functional properties of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIgamma variants isolated from smooth muscle. Biochem. J. 2003, 372, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, C.B.; Heller Brown, J. CaMKIIdelta subtypes: Localization and function. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brocke, L.; Chiang, L.W.; Wagner, P.D.; Schulman, H. Functional implications of the subunit composition of neuronal CaM kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 22713–22722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebenebe, O.V.; Heather, A.; Erickson, J.R. CaMKII in Vascular Signalling: “Friend or Foe”? Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, J.R.; Joiner, M.L.; Guan, X.; Kutschke, W.; Yang, J.; Oddis, C.V.; Bartlett, R.K.; Lowe, J.S.; O’Donnell, S.E.; Aykin-Burns, N.; et al. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell 2008, 133, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erickson, J.R.; Nichols, C.B.; Uchinoumi, H.; Stein, M.L.; Bossuyt, J.; Bers, D.M. S-Nitrosylation Induces Both Autonomous Activation and Inhibition of Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II delta. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 25646–25656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erickson, J.R.; Pereira, L.; Wang, L.; Han, G.; Ferguson, A.; Dao, K.; Copeland, R.J.; Despa, F.; Hart, G.W.; Ripplinger, C.M.; et al. Diabetic hyperglycaemia activates CaMKII and arrhythmias by O-linked glycosylation. Nature 2013, 502, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, B.; Fasoli, A.; Ko, C.Y.; Van, B.W.; Alim, C.C.; Shen, E.Y.; Ciccozzi, M.M.; Tapa, S.; Ripplinger, C.M.; Erickson, J.R.; et al. CaMKII Serine 280 O-GlcNAcylation Links Diabetic Hyperglycemia to Proarrhythmia. Circ. Res. 2021, 129, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, B.; Meyer, R.; Hetzer, R.; Krause, E.G.; Karczewski, P. Identification and expression of delta-isoforms of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, H.; Liu, D.; Zhong, X.; Shi, X.; Yu, P.; Jin, L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Song, Y.; et al. CaMKII-delta9 promotes cardiomyopathy through disrupting UBE2T-dependent DNA repair. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.; Nickel, L.; Estrada, M.; Backs, J.; van den Hoogenhof, M.M.G. CaMKIIdelta Splice Variants in the Healthy and Diseased Heart. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 644630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddouk, F.Z.; Ginnan, R.; Singer, H.A. Ca(2+)/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II in Vascular Smooth Muscle. Adv. Pharmacol. 2017, 78, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, G.H.; Saw, A.; Bai, Y.; Dow, J.; Marjoram, P.; Simkhovich, B.; Leeka, J.; Kedes, L.; Kloner, R.A.; Poizat, C. Critical role of nuclear calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdeltaB in cardiomyocyte survival in cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 24857–24868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramirez, M.T.; Zhao, X.L.; Schulman, H.; Brown, J.H. The nuclear deltaB isoform of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates atrial natriuretic factor gene expression in ventricular myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31203–31208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Maier, L.S.; Dalton, N.D.; Miyamoto, S.; Ross, J., Jr.; Bers, D.M.; Brown, J.H. The deltaC isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, X.; Yang, D.; Ding, J.H.; Wang, W.; Chu, P.H.; Dalton, N.D.; Wang, H.Y.; Bermingham, J.R., Jr.; Ye, Z.; Liu, F.; et al. ASF/SF2-regulated CaMKIIdelta alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell 2005, 120, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, M.; Edman, C.F.; Schulman, H. Alternative splicing introduces a nuclear localization signal that targets multifunctional CaM kinase to the nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 126, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Backs, J.; Song, K.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Chang, S.; Olson, E.N. CaM kinase II selectively signals to histone deacetylase 4 during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, L.S.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; DeSantiago, J.; Brown, J.H.; Bers, D.M. Transgenic CaMKIIdeltaC overexpression uniquely alters cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling: Reduced SR Ca2+ load and activated SR Ca2+ release. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saddouk, F.Z.; Sun, L.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Jiang, M.; Singer, D.V.; Backs, J.; Van Riper, D.; Ginnan, R.; Schwarz, J.J.; Singer, H.A. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-gamma (CaMKIIgamma) negatively regulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and vascular remodeling. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 1051–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurjar, M.V.; Sharma, R.V.; Bhalla, R.C. eNOS gene transfer inhibits smooth muscle cell migration and MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity. ATVB 1999, 19, 2871–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudijanto, A. The role of vascular smooth muscle cells on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Acta Med. Indones. 2007, 39, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.R.; Sinbeha, S.; Owens, G.K. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Gratton, J.P.; Rafikov, R.; Black, S.M.; Fulton, D.J. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates the phosphorylation and activation of NADPH oxidase 5. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 80, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauly, R.R.; Bilato, C.; Sollott, S.J.; Monticone, R.; Kelly, P.T.; Lakatta, E.G.; Crow, M.T. Role of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circulation 1995, 91, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A.; Klutho, P.J.; El Accaoui, R.; Nguyen, E.; Venema, A.N.; Xie, L.; Jiang, S.; Dibbern, M.; Scroggins, S.; Prasad, A.M.; et al. The multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IIdelta (CaMKIIdelta) regulates arteriogenesis in a mouse model of flow-mediated remodeling. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erickson, J.R.; He, B.J.; Grumbach, I.M.; Anderson, M.E. CaMKII in the cardiovascular system: Sensing redox states. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 889–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balasubramaniam, V.; Le Cras, T.D.; Ivy, D.D.; Grover, T.R.; Kinsella, J.P.; Abman, S.H. Role of platelet-derived growth factor in vascular remodeling during pulmonary hypertension in the ovine fetus. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2003, 284, L826–L833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfleiderer, P.J.; Lu, K.K.; Crow, M.T.; Keller, R.S.; Singer, H.A. Modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration by calcium/ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-delta 2. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2004, 286, C1238–C1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.F.; Spinelli, A.; Sun, L.Y.; Jiang, M.; Singer, D.V.; Ginnan, R.; Saddouk, F.Z.; Van Riper, D.; Singer, H.A. MicroRNA-30 inhibits neointimal hyperplasia by targeting Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdelta (CaMKIIdelta). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, J.A.; Xie, L.; Li, H.; Li, W.; He, J.B.; Sanders, P.N.; Carter, A.B.; Backs, J.; Anderson, M.E.; Grumbach, I.M. The multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulates vascular smooth muscle migration through matrix metalloproteinase 9. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H1953–H1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundberg, M.S.; Curto, K.A.; Bilato, C.; Monticone, R.E.; Crow, M.T. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle migration by mitogen-activated protein kinase and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signaling pathways. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998, 30, 2377–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebak, M.; Ginnan, R.; Singer, H.A.; Jourd’heuil, D. Interplay between calcium and reactive oxygen/nitrogen species: An essential paradigm for vascular smooth muscle signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.J.; Klutho, P.J.; Scott, J.A.; Xie, L.; Luczak, E.D.; Dibbern, M.E.; Prasad, A.M.; Jaffer, O.A.; Venema, A.N.; Nguyen, E.K.; et al. Oxidative activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) regulates vascular smooth muscle migration and apoptosis. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 60, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, A.; Reidy, M.A. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is necessary for the regulation of smooth muscle cell replication and migration after arterial injury. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, C.; Galis, Z.S. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 differentially regulate smooth muscle cell migration and cell-mediated collagen organization. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nishio, S.; Teshima, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Thuc, L.C.; Saito, S.; Fukui, A.; Kume, O.; Fukunaga, N.; Hara, M.; Nakagawa, M.; et al. Activation of CaMKII as a key regulator of reactive oxygen species production in diabetic rat heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 52, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.N.; Shi, N.; Chen, S.Y. Manganese superoxide dismutase inhibits neointima formation through attenuation of migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, E.K.; Koval, O.M.; Noble, P.; Broadhurst, K.; Allamargot, C.; Wu, M.; Strack, S.; Thiel, W.H.; Grumbach, I.M. CaMKII (Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II) in Mitochondria of Smooth Muscle Cells Controls Mitochondrial Mobility, Migration, and Neointima Formation. ATVB 2018, 38, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prudent, J.; Popgeorgiev, N.; Gadet, R.; Deygas, M.; Rimokh, R.; Gillet, G. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake controls actin cytoskeleton dynamics during cell migration. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mallilankaraman, K.; Doonan, P.; Cardenas, C.; Chandramoorthy, H.C.; Muller, M.; Miller, R.; Hoffman, N.E.; Gandhirajan, R.K.; Molgo, J.; Birnbaum, M.J.; et al. MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell 2012, 151, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, M.F.; Phillips, C.B.; Ranaghan, M.; Tsai, C.W.; Wu, Y.; Willliams, C.; Miller, C. Dual functions of a small regulatory subunit in the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex. Elife 2016, 5, e15545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokolya, A.; Singer, H.A. Inhibition of CaM kinase II activation and force maintenance by KN-93 in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2000, 278, C537–C545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cipolletta, E.; Monaco, S.; Maione, A.S.; Vitiello, L.; Campiglia, P.; Pastore, L.; Franchini, C.; Novellino, E.; Limongelli, V.; Bayer, K.U.; et al. Calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and is potentiated by extracellular signal regulated kinase. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2747–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, S.J.; Potier, M.; Bisaillon, J.; Singer, H.A.; Trebak, M. The non-excitable smooth muscle: Calcium signaling and phenotypic switching during vascular disease. Pflug. Arch. 2008, 456, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarron, J.G.; McGeown, J.G.; Reardon, S.; Ikebe, M.; Fay, F.S.; Walsh, J.V., Jr. Calcium-dependent enhancement of calcium current in smooth muscle by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nature 1992, 357, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, A.; Menice, C.B.; Laporte, R.; Morgan, K.G. Mechanisms of smooth muscle contraction. Physiol. Rev. 1996, 76, 967–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamhoff, B.R.; Bowles, D.K.; Owens, G.K. Excitation-transcription coupling in arterial smooth muscle. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, L.Y.; Singer, D.V.; Ginnan, R.; Zhao, W.; Jourd’heuil, F.L.; Jourd’heuil, D.; Long, X.; Singer, H.A. Thymine DNA glycosylase is a key regulator of CaMKIIgamma expression and vascular smooth muscle phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317, H969–H980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Leslie, K.L.; Martin, K.A. Epigenetic regulation of smooth muscle cell plasticity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1849, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Jin, Y.; Tang, W.H.; Qin, L.; Zhang, X.; Tellides, G.; Hwa, J.; Yu, J.; Martin, K.A. Ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET2) is a master regulator of smooth muscle cell plasticity. Circulation 2013, 128, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Y.F.; Li, B.Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Ding, J.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science 2011, 333, 1303–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.Z.; Li, S.; Hockemeyer, D.; Sutherland, L.; Wang, Z.; Schratt, G.; Richardson, J.A.; Nordheim, A.; Olson, E.N. Potentiation of serum response factor activity by a family of myocardin-related transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14855–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, T.; Kaestner, K.H.; Owens, G.K. Conditional deletion of Kruppel-like factor 4 delays downregulation of smooth muscle cell differentiation markers but accelerates neointimal formation following vascular injury. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 1548–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christman, J.K. 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation: Mechanistic studies and their implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene 2002, 21, 5483–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cordes, K.R.; Sheehy, N.T.; White, M.P.; Berry, E.C.; Morton, S.U.; Muth, A.N.; Lee, T.H.; Miano, J.M.; Ivey, K.N.; Srivastava, D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature 2009, 460, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cha, M.J.; Jang, J.K.; Ham, O.; Song, B.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.; Seo, H.H.; Choi, E.; et al. MicroRNA-145 suppresses ROS-induced Ca2+ overload of cardiomyocytes by targeting CaMKIIdelta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2013, 435, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocerha, J.; Faghihi, M.A.; Lopez-Toledano, M.A.; Huang, J.; Ramsey, A.J.; Caron, M.G.; Sales, N.; Willoughby, D.; Elmen, J.; Hansen, H.F.; et al. MicroRNA-219 modulates NMDA receptor-mediated neurobehavioral dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3507–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, H.; Tang, R.; Yao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Peng, F.; Wang, W.; Can, D.; Xing, H.; et al. MiR-219 Protects Against Seizure in the Kainic Acid Model of Epilepsy. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.M.; Cao, S.B.; Zhang, H.L.; Lyu, D.M.; Chen, L.P.; Xu, H.; Pan, Z.Q.; Shen, W. Downregulation of miR-219 enhances brain-derived neurotrophic factor production in mouse dorsal root ganglia to mediate morphine analgesic tolerance by upregulating CaMKIIgamma. Mol. Pain 2016, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Shao, J.; He, Z.; Ding, Z.; Huang, J.; Guo, Q.; Zou, W. miR-219-5p targets CaMKIIgamma to attenuate morphine tolerance in rats. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28203–28214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, Z.; Zhu, L.J.; Li, Y.Q.; Hao, L.Y.; Yin, C.; Yang, J.X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hua, L.; Xue, Z.Y.; et al. Epigenetic modification of spinal miR-219 expression regulates chronic inflammation pain by targeting CaMKIIgamma. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 9476–9483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prasad, A.M.; Morgan, D.A.; Nuno, D.W.; Ketsawatsomkron, P.; Bair, T.B.; Venema, A.N.; Dibbern, M.E.; Kutschke, W.J.; Weiss, R.M.; Lamping, K.G.; et al. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II inhibition in smooth muscle reduces angiotensin II-induced hypertension by controlling aortic remodeling and baroreceptor function. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e001949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, T.; Abdel Rahman, F.; Jurisch, V.; Kupatt, C. Atherosclerosis and the Capillary Network; Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Cells 2019, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Li, W.; Gupta, A.K.; Mohler, P.J.; Anderson, M.E.; Grumbach, I.M. Calmodulin kinase II is required for angiotensin II-mediated vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2010, 298, H688–H698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helmstadter, K.G.; Ljubojevic-Holzer, S.; Wood, B.M.; Taheri, K.D.; Sedej, S.; Erickson, J.R.; Bossuyt, J.; Bers, D.M. CaMKII and PKA-dependent phosphorylation co-regulate nuclear localization of HDAC4 in adult cardiomyocytes. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2021, 116, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Huang, J.; Chen, L.; Han, G.; Stanmore, D.; Krebs-Haupenthal, J.; Avkiran, M.; Hagenmuller, M.; Backs, J. Cyclic AMP represses pathological MEF2 activation by myocyte-specific hypo-phosphorylation of HDAC5. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 145, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Joshi, S.; Speransky, S.; Crowley, C.; Jayathilaka, N.; Lei, X.; Wu, Y.; Gai, D.; Jain, S.; Hoosien, M.; et al. Reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy via the MEF2-coregulator interface. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e91068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, X.; Ha, C.H.; Wong, C.; Wang, W.; Hausser, A.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Olson, E.N.; McKinsey, T.A.; Jin, Z.G. Angiotensin II stimulates protein kinase D-dependent histone deacetylase 5 phosphorylation and nuclear export leading to vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy. ATVB 2007, 27, 2355–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backs, J.; Backs, T.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; McKinsey, T.A.; Olson, E.N. Histone deacetylase 5 acquires calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II responsiveness by oligomerization with histone deacetylase 4. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 3437–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muthalif, M.M.; Karzoun, N.A.; Benter, I.F.; Gaber, L.; Ljuca, F.; Uddin, M.R.; Khandekar, Z.; Estes, A.; Malik, K.U. Functional significance of activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in angiotensin II--induced vascular hyperplasia and hypertension. Hypertension 2002, 39 Pt 2, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roberts-Craig, F.T.; Worthington, L.P.; O’Hara, S.P.; Erickson, J.R.; Heather, A.K.; Ashley, Z. CaMKII Splice Variants in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: The Next Step or Redundancy? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147916

Roberts-Craig FT, Worthington LP, O’Hara SP, Erickson JR, Heather AK, Ashley Z. CaMKII Splice Variants in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: The Next Step or Redundancy? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(14):7916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147916

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoberts-Craig, Finn T., Luke P. Worthington, Samuel P. O’Hara, Jeffrey R. Erickson, Alison K. Heather, and Zoe Ashley. 2022. "CaMKII Splice Variants in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: The Next Step or Redundancy?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 14: 7916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147916