Supramolecular Crystal Networks Constructed from Cucurbit[8]uril with Two Naphthyl Groups

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Molecular Binding Behavior and Thermodynamic between Cucurbit[8]uril and NapA or Nap1

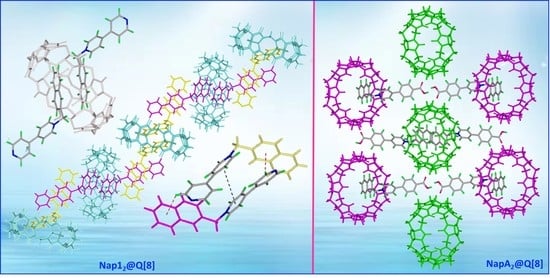

2.2. Single-Crystal X-ray Crystallography

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Busseron, E.; Ruff, Y.; Moulin, E.; Giuseppone, N. Supramolecular self-assemblies as functional nanomaterials. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 7098–7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, P.; Yan, X.; Huang, F. Supramolecular polymers constructed by orthogonal self-assembly based on host–guest and metal–ligand interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ariga, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Mori, T.; Takeya, J.; Shrestha, L.K.; Hill, J.P. Self-assembly as a key player for materials nanoarchitectonics. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 51–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, X.; Gao, A.; Hou, J.-T.; Yi, T. Fluorescent supramolecular self-assembly gels and their application as sensors: A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 434, 213792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, L.; Ballester, P. Molecular recognition in water using macrocyclic synthetic receptors. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 2445–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Z.; Tian, C.-B.; Sun, Q.-F. Coordination-Directed Self-Assembly of Functional Polynuclear Lanthanide Supramolecular Architectures. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 6374–6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-X.; Zhong, Q.-Y.; Wang, S.-J.; Wu, Y.-S.; Tan, J.-D.; Lei, H.-X.; Huang, S.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-F. Progress in dynamic covalent polymers. Acta Polym. Sin. 2019, 50, 469–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Zhao, M.-H.; Zhang, C. Recent advance in applications of host-guest interaction in biochemical analysis. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2020, 48, 817–826. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.-J.; Oh, H.-G.; Cha, S.-H. A brief review of self-healing polyurethane based on dynamic chemistry. Macromol. Res. 2021, 29, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H. Constructions and Properties of Physically Cross-Linked Hydrogels Based on Natural Polymers. Polym. Rev. 2022, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Wang, P.; Ji, X.; Khashab, N.M.; Sessler, J.L.; Huang, F. Functional supramolecular polymeric networks: The marriage of covalent polymers and macrocycle-based host–guest interactions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6070–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Yu, S.B.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, C.Z.; Lu, S.; Cao, J.; Qi, Q.Y.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Porous Polymers as Universal Reversal Agents for Heparin Anticoagulants through an Inclusion–Sequestration Mechanism. Adv. Mater. 2022, 2022, 2200549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-C.; Zeng, P.-Y.; Ma, Z.-Q.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Wang, Z.-K.; Guo, B.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.-T. A pH-responsive complex based on supramolecular organic framework for drug-resistant breast cancer therapy. Drug Delivery 2022, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Yan, X. Synergistic Covalent-and-Supramolecular Polymers with an Interwoven Topology. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, P.; Hu, J.; Liu, M.; Tao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Redshaw, C. Progress in host–guest macrocycle/pesticide research: Recognition, detection, release and application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 467, 214580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Supramolecular Polymer Chemistry: Past, Present, and Future. Chinese J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 40, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Samal, S.; Selvapalam, N.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, K. Cucurbituril homologues and derivatives: New opportunities in supramolecular chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, S.J.; Kasera, S.; Rowland, M.J.; Del Barrio, J.; Scherman, O.A. Cucurbituril-based molecular recognition. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12320–12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Yu, H.J.; Liu, Y. Cucurbituril-Based Biomacromolecular Assemblies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3870–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Hua, Z.-Y.; Zhao, J.-L.; Redshaw, C.; Tao, Z. Construction of cucurbit[n]uril-based supramolecular frameworks via host–guest inclusion and functional properties thereof. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 2753–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.H.; Chen, L.X.; Chen, K.; Tao, Z.; Xiao, X. Development of hydroxylated cucurbit[n]urils, their derivatives and potential applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 348, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, M.; Xiao, X.; Tao, Z.; Redshaw, C. Polymeric self-assembled cucurbit[n]urils: Synthesis, structures and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 434, 213733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Shan, P.; Lian, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Z.; Xiao, X. Pyridine detection using supramolecular organic frameworks incorporating cucurbit[10]uril. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7434–7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gao, R.H.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.X.; Ni, X.L.; Xiao, X.; Cong, H.; Zhu, Q.J.; Chen, K.; Tao, Z. Cucurbit[n]uril-Based Supramolecular Frameworks Assembled through Outer-Surface Interactions. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 15294–15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, Y.; Ni, X.-L.; Tao, Z.; Xiao, X. Two-step, Sequential, Efficient, Artificial Light-harvesting Systems Based on Twisted Cucurbit[13]uril for Manufacturing White Light Emission Materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 2022, 136954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, M.-X.; Feng, X.-H.; Redshaw, C.; Li, Q.; Tao, Z.; Xiao, X. A Twisted Cucurbit[14]uril-Based Fluorescent Supramolecular Polymer Mediated by Metal Ion. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.-A.; Zhou, Q.-Y.; Dai, X.; Ma, X.-K.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Cucurbit[8]uril-mediated phosphorescent supramolecular foldamer for antibiotics sensing in water and cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Luo, Y.; Rao, Y.; Song, J.; Ni, X.-L. Cucurbit[7]uril-Encapsulation-Controlled Supramolecular Photoproduct and Radical Fluorescence Emission. Chem.-Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202202056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xia, Y.; Tao, Z.; Ni, X.-L. Host-guest interaction tailored cucurbit[6]uril-based supramolecular organic frameworks (SOFs) for drug delivery. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 1529–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.-Z.; Lin, R.-L.; Bai, D.; Tao, Z.; Liu, J.-X.; Xiao, X. Host-guest complexation of cucurbit[8]uril with two enantiomers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, B.; Yu, S.-B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.-W.; Li, Z.-T. 2: 2 Complexes from Diphenylpyridiniums and Cucurbit[8]uril: Encapsulation-Promoted Dimerization of Electrostatically Repulsing Pyridiniums. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shen, F.-F.; Sun, J.-F.; Gao, Z.-Z. Cucurbit[8]uril-controlled [2+ 2] photodimerization of styrylpyridinium molecule. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 141, 109536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Ma, X.; Tian, H. Visible-light-excited room-temperature phosphorescence in water by cucurbit[8]uril-mediated supramolecular assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9928–9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Miao, X.; Qin, C.; Chu, D.; Cao, L. Adaptive Chirality of an Achiral Cucurbit[8]uril-Based Supramolecular Organic Framework for Chirality Induction in Water. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 6818–6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, C.; Li, Q.; Cao, L. Successive construction of cucurbit[8]uril-based covalent organic frameworks from a supramolecular organic framework through photochemical reactions in water. Sci. China Chem. 2022, 65, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Bai, Y.; Yu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Supramolecular polymers bearing disulfide bonds. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 6439–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, K.; Kelgtermans, H.; Dehaen, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Porphyrin-containing hyperbranched supramolecular polymers: Enhancing 1O2-generation efficiency by supramolecular polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.Y.; Huo, M.; Dong, X.; Hu, Y.Y.; Liu, Y. Noncovalent Polymerization-Activated Ultrastrong Near-Infrared Room-Temperature Phosphorescence Energy Transfer Assembly in Aqueous Solution. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2203534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Wei, Z.; Ni, X.-L.; Liu, Y. Assembly and Applications of Macrocyclic-Confinement-Derived Supramolecular Organic Luminescent Emissions from Cucurbiturils. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 9032–9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhou, T.-Y.; Zhang, S.-C.; Aloni, S.; Altoe, M.V.; Xie, S.-H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.-W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y. Three-dimensional periodic supramolecular organic framework ion sponge in water and microcrystals. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, J.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, D.-W.; Wang, H.; Xie, S.-H.; Xu, D.-W.; Ren, Y.-H.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.-T. Supramolecular metal-organic frameworks that display high homogeneous and heterogeneous photocatalytic activity for H2 production. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gao, Z.-Z.; Wang, Z.-K.; Wei, L.; Yin, G.; Tian, J.; Liu, C.-Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.-W.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Li, X.; et al. Water-soluble 3D covalent organic framework that displays an enhanced enrichment effect of photosensitizers and catalysts for the reduction of protons to H2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 12, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.-Z.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Wang, Z.-K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.-W.; Li, Z.-T. Porous [Ru(bpy)3]2+-Cored Metallosupramolecular Polymers: Preparation and Recyclable Photocatalysis for the Formation of Amides and 2-Diazo-2-phenylacetates. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 4885–4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.C.; Leach, D.G.; Blaylock, B.E.; Ali, O.A.; Urbach, A.R. Sequence-specific, nanomolar peptide binding via cucurbit[8]uril-induced folding and inclusion of neighboring side chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3663–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ko, Y.H.; Kim, E.; Hwang, I.; Kim, K. Supramolecular assemblies built with host-stabilized charge-transfer interactions. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Z.-Z.; Shen, L.; Hu, Y.-L.; Sun, J.-F.; Wei, G.; Zhao, H. Supramolecular Crystal Networks Constructed from Cucurbit[8]uril with Two Naphthyl Groups. Molecules 2023, 28, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010063

Gao Z-Z, Shen L, Hu Y-L, Sun J-F, Wei G, Zhao H. Supramolecular Crystal Networks Constructed from Cucurbit[8]uril with Two Naphthyl Groups. Molecules. 2023; 28(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Zhong-Zheng, Lei Shen, Yu-Lu Hu, Ji-Fu Sun, Gang Wei, and Hui Zhao. 2023. "Supramolecular Crystal Networks Constructed from Cucurbit[8]uril with Two Naphthyl Groups" Molecules 28, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010063