1. Introduction

Teary eyed, I wrote this poem on my mother’s second birthday following her sunset on 18 June 2017. My mom took her last breath on an air mattress in a government subsidy apartment, just six years after her mother with a similar socioeconomic status passed in a hospital bed. Some of my tears resulted from a small fear that I could have a similar fate. While mourning, I began to wonder how things got to be the way they had for my family.

I was raised by the maternal side of my family, and my grandmother was the oldest living relative I knew. Before middle school, I did not realize that I finished my family tree assignment before everyone else because I was not including paternal relatives. Despite how peculiar it felt to sit and wait for others to complete their family trees, I was content with my mom’s claim that our family tree was just as large as my classmates. Since my grandmother relocated to California from Texas, I had simply never met everyone.

Sitting in bed reflecting on my mom’s life choices, I recalled how difficult it was to get her to try new things, go places by herself, and leave Los Angeles when the rental payments became too expensive. Memories of my mother increased my awareness of my grandmother’s strength. Before the Internet and mobile access to the Global Positioning System (GPS), my grandmother took the leap I struggled to get my mother to take. She, an African-American single mother of three, left Texas with three children and relocated to California in the middle of the civil rights movement. What compelled her to relocate? What gave her the strength and courage to do such a thing? What did the family in Texas think of her decision? Could this explain why I did not meet them?

My grandmother’s decisions influenced my maternal family’s trajectory. I spent much of my adult life frustrated about the way the racial climate and structural oppression in Los Angeles, California, normalized negative experiences for me and my loved ones, but I never spent time thinking about what life could have been if my grandmother had not decided to leave Texas. Sleeter (

Christine Sleeter n.d.) explains a critical family history as a framework that situates the self in a sociocultural context and uses multiple generations to understand the exchange between past and present. Similar to

Hickson (

2016), who has used a combination of narrative and critically reflective research approaches to deconstruct and explore an individual’s story and experience, this research is based on stories as data about my grandmother Eula Mae, interpreted using Black Feminist Theory. The uniqueness of this article is that it highlights the civil rights era migration experience of a Black woman, which is rarely documented in detail. This account also presents readers with a structural view of generational poverty, which can be better understood through genealogical studies. Combining information passed down from relatives, artifacts obtained through Ancestry.com, and research on relevant historical events and laws, I present this critical family history (using pseudonyms for living relatives) as a narrative about my grandmother’s journey to create a

new normal for her children.

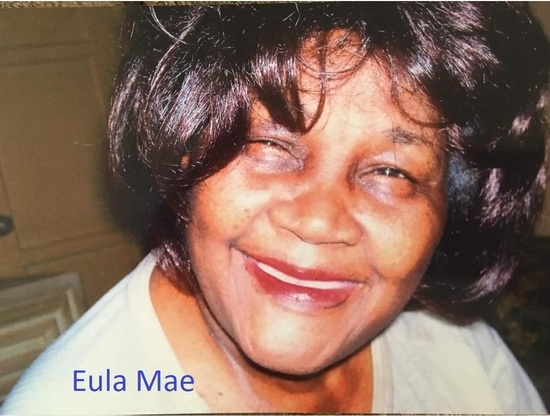

3. Eula Mae

My grandmother, Eula Mae, was born on 8 March 1932, in Sherman, Texas, and she passed in Los Angeles, California, on 4 November 2011. She left behind six children, nine grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. She was a dignified woman, full of traditions, superstitions, and strength. Many knew her by her preferred ensemble: black slacks, cream satin blouse, burgundy lipstick, a wig, and her briefcase. I knew her by her walk; a swift rhythmic pace that caused her shoulders to rock as she moved her bowlegged limbs with the ferocity of someone 6 foot instead of 5′4”. I knew her by her laugh; high-pitched excitement that would escape her before being followed by a cough or gurgle, likely emerging to clear tobacco from her lungs. By her resilience; her ability to catch several buses and trains across greater Los Angeles County to retrieve her grandchildren from her kids when she disapproved of living conditions or circumstances, all while neglecting personal mental and emotional health needs. Her stubbornness; her inflexible decision to live in the here-and-now and minimize conversation about the past, leaving my younger self yearning to know more about my family matriarch. A petite chain-smoking Black woman who read the Bible every morning, drank coffee and Coca-Cola every day and didn’t leave the house without Wrigley’s gum or her briefcase. On several occasions, I witnessed my grandmother promptly let a person know, if you messed with her or her family, she would hit them in the head with a brick so hard “it will make you shit blood.”

3.1. Firstborn

Eula Mae was the firstborn of her parents’ six or seven children (note: while I know of six children, I recall my grandmother mentioning a child that was born and named who did not survive, and I feel fairly confident Eula may have had another sibling). Some research suggests firstborn children are more likely to be mature, responsible, and conscientious (

Eckstein 2000). I suspect these characteristics were developed in Eula during her childhood. Research also suggests that parents can provide the greatest advantages to firstborns before resources decline with the addition of subsequent children (

Downey 2001). Since her siblings were close in age, my grandmothers’ period of attention and resources may have ended swiftly when her sister was born just a year after her.

3.2. New Knowledge

The most incomplete and misconstrued portion of my account of my grandmother was about her childhood. The initial attempt to understand her youth relied heavily on stories passed down from my mother, documents found online, and inferences made based on my experience of Eula. However, questions asked during the submission process for this article emphasized my need to critique assumptions and dig deeper. I dug myself into a series of phone calls with living relatives, including someone I had never before spoken to (Eula’s paternal first cousin who relocated to California in 1962) and her youngest daughter Kathren. Due to a family rift, my aunt Kathren and I stopped speaking in 2018. Overlooking past transgressions, we spent an hour bonding about her “momma” and her recollection of Eula’s upbringing described to her by her older siblings, her aunts and uncles, and Eula herself. The most paramount portions of the conversation were almost accidentally revealed. “As the oldest, she always felt bad about not being there for her parents. You know, it was her responsibility to take care of them when they got older,” said Kathren. What appeared to be a word accidentally used in plural form, was a key to my grandmother’s story. My grandmother’s mom had not passed in 1948 as my Ancestry.com research first indicated. Instead, she had lived to be 90 years old, passing in 1999 when my grandmother was 68 years of age. I went back to the drawing board after the phone call and learned the root of my mistake; I misspelled the first name.

My great-grandmother’s name was Chorlsie with an

o, instead of Charlsie with

a, and the use of the wrong spelling caused me to paint a very different picture of my grandmother’s experience than my aunt described. Opposite of my initial beliefs, Eula was raised in a two-parent household and had a positive relationship with her grandmother, whom she was named after. Her grandparents Eula and Earnie Banges were extremely fond of their granddaughter, and her childhood consisted of trips to their farm where she was able to ride their horses, cooking lessons, love, and affection. To see a more accurate depiction of my maternal family tree, please refer to

Figure A1 of this articles Appendix. Despite being a favorite amongst the grandchildren, my grandmother’s childhood experience wasn’t enough to keep her Texas bound. Her paternal first cousin Sam grew up knowing my grandmother by her nickname

Tootsie. Her cousin said during our phone call, “Tootsie always wanted to leave. She was brave and wasn’t scared of nothing. I guess California just sounded good.” I suspect it was Eula’s inner courage that helped her follow through with her plans, but it may have been a frustration with her geographical surroundings that made her dream of a departure.

4. Her Texas

Just nineteen years before the abolition of slavery in 1865, on 17 May 1846, Grayson County Texas was founded (

Texas Escapes n.d.). In 1930, the population of Grayson was approximately 66,000 (

Kumler n.d.), and Sherman was a small area in that county. As a child, my grandmother worked on a farm and helped her parents pick crops. I had forgotten this until I viewed the 1940s census records on Ancestry.com and saw that my great-grandmother listed farmer as her occupation. When watching movies like Roots, based on the book by Alex Haley, with scenes of people who were enslaved picking cotton, I would say, “look Grandma! Wouldn’t it be horrible to pick cotton?” and she’d say, “picking fruit or beans wouldn’t be no better.” My aunt Loren remembered hearing Eula and her siblings brag about the best okra and greens being those they grew growing up. I wondered if farming was something Eula was ever passionate about. As the firstborn of her siblings, I suspect she bore the brunt of domestic responsibilities, making farm life and agricultural work more likely to be a means to an end than a passion for her.

I struggled to find a lot of documentation on my maternal great-great-grandparents; however, my aunts helped to fill in gaps. Eula’s father (Herman, my great-grandfather) was a hardworking breadwinner for the family. He was well known in Grayson, and Eula was “daddy’s little girl.” My grandmother was also raised near her paternal grandparents, Steve and Eliza Dooley, and extended maternal and paternal relatives. Herman was a twin who had 11 siblings and there was an abundance of aunts, uncles, and cousins in my grandmother’s life. Whether she viewed having all the additional family members around her as an asset or liability is still unknown.

She must have found clever ways to escape the relatives for at least short periods, because at age 17 she became pregnant with her first child. In February 1950 when she gave birth, she was a 17-year-old, unwed mother in her parents’ household, assisting with five younger siblings, and living in a rural place with 20,000 residents. I asked her cousin Sam if she could recall my grandmother working in Texas outside of farm life. “I don’t really recall what other jobs she had, but I do know her father rented a hamburger joint she use to run. She did good too.” By the time I was born, my grandmother had limited her kitchen appearances to scrambling eggs and bacon, pouring milk in bowls of cereal, microwaving noodles, and making cups of coffee. I listened to Sam in awe as I tried to visualize images of her wearing a uniform, taking food orders, and flipping patties. Sam, being younger than my grandmother, couldn’t remember a specific timeline for this job, but since she believed my grandmother used some of her earnings to move to California, I am guessing she worked there post parenthood, and in her early twenties. As highlighted in the work of

Hine (

1989), histories of 20th century Black women’s experiences reveal themes of frustration finding suitable employment and greater economic discrimination than that faced by Black men.

The burger stand was likely a great investment that allowed her to obtain a non-domestic employment opportunity while Sherman was experiencing a season of growth. During that period, industrial plants and companies like Texas Instruments, IBM, and Johnson and Johnson opened in the 1950s (

City of Sherman n.d.), around the time my grandmother was experiencing an ever-growing desire to leave. I wonder if her affinity for Texas dried up with the drought. In 1953, 75% of Texas “recorded below-normal amounts of rainfall” (

Texas Water Resources 1996, p. 4), and before the end in 1957, all but 10 of the state’s 254 counties had been declared as federal drought disaster areas (

Burnett 2012). It is possible that the drought, coupled with hardships experienced by many Black farmers (

Zain 2010), and the negative racial climate implied by the Sherman Riot, had added to her desire to move.

4.1. Sherman Riot

Eula entered this world amid the Great Depression, and her birth came less than two years after the Sherman Riot of 1930. This riot, which resulted after a Black farmhand named George Hughes admitted to raping a White woman, gives insight into the racial climate of that community. According to Texas State Library and Archives Commission (

TSLAC 2019), during the trial for this case, an angry mob surrounded the courthouse and stoned it before setting it on fire. The National Guard had to be called in to subdue the mob; however, Hughes perished in the fire before his body was dragged behind a car, hung from a tree, and burned along with multiple Black businesses.

Raising Racists:

The socialization of White Children in The Jim Crow South (

DuRocher 2011) adds to my understanding of the Sherman Riot. The author recalls a grandmother who got her grandson from bed so that he could observe a mob, including a multitude of young boys, who “proceeded to sexually mutilate the forty-one-year-old Black man before burning him alive” (104). In 1950, when my 18-year-old grandmother put my Aunt Vanessa to sleep, I wonder if knowledge of local incidents like this riot fueled her desire to find a new way.

4.2. Noneconomic Motives

In addition to a desire to obtain economic stability by escaping the racist South, many Black women left the South “out of a desire to achieve personal autonomy and to escape both from sexual exploitation from inside and outside of their families and from the rape and threat of rape by White as well as Black males” (

Hine 1989, p. 914). Scholar

Evelyn M. Simien (

2004) explains that African-American women lagged behind other groups on measures of employment and education, leaving them subject to a multitude of burdens such as joblessness, domestic violence, teenage pregnancy, illiteracy, poverty, and sometimes malnutrition. Aunt Loren believed my grandmother finished high school in Texas, shortly before or after the birth of her first child. The timeline of Vanessa’s birth confirmed Eula’s experience of teenage pregnancy, which my cousin pointed out wasn’t too much of a big deal back then, when people often got married young. The biggest issue was likely the embarrassment of not being in a legally binding agreement with her children’s fathers and having her family present to witness her experience several failed relationships.

4.3. Romance Over Hopelessness

An eye-opening portion of this research resulted from my desire to identify prospective reasons for my grandmother’s relocation. I was curious about her making the journey without the fathers of her first three children. My father passed before I turned nine and I primarily grew up in a single-parent household, so I understood “dads” not being around. However, during my childhood years, I didn’t understand why my mom had the same last name as my grandmother and not her father. “Why do you, aunt V, and Uncle Marvin have the same last name, but grandma said she didn’t marry your dad?” I once asked. My mom explained that they all had different fathers and Grandma had chosen to give them all her last name.

As an adult, I was intrigued by the timeline. Her first three children were all born within six years of each other. Was she in love with all of these men? Did they disapprove of her desire to move, or was her desire to move a result of the failed relationships? Did they not want children? Is that why she gave her children her maternal last name?

Figure 1 helps illustrate the timeline.

Timeline of children’s birth (see

Figure 1).

My grandmother never talked openly about her first three children’s biological fathers. Comments made by family members suggested that my grandmother was full of beauty and had a fearless charm and personality that attracted the attention of a lot of suitors. That attention typically came without fidelity or long-term commitment. Between 1949 and 1955, she conceived and carried three children, indicating that she was pregnant 27 (9 × 3) out of 72 months. In that time, she met men, dated them, became romantically involved with them, sometimes had children with them, ended relationships, and started anew several times, so it would appear she possessed the ability to swiftly rebound after a relationship was terminated. I am astounded by thoughts of her willingness to continue dating, and I view this as implied optimism that Mr. Right was still worth pursuing. I am also cognizant of the possibility that my grandmother was more fueled by a desire for physical affection than emotional connections. Due to negative stereotypes about Black sexuality, Black women often felt compelled to downplay and deny their sexual expression (

Hine 1989). Though Margaret Sanger helped make diaphragms popular in the 1930s and condoms were available, I am not sure if my grandmother was aware of contraceptive options, or if she believed in terminating pregnancies. It’s possible that Eula didn’t mind the short-lived relationships and didn’t at that time desire a marital union. However, I find it more likely that she genuinely sought a partner who could give her a marriage like those of the parents and grandparents who raised her.

One of the biggest revelations on this journey to research my grandmother’s past came from a biological discovery. My mother told me my grandmother had given her the name of her biological father, but she couldn’t confirm it was accurate: “Horace Speed,” she said, after sharing that my grandmother’s brother Scoe had once confirmed hearing about someone with that name. Growing up in Los Angeles, I heard of adults being addicted to a drug called speed, so that last name was embedded in my memory. This name came up again after an Ancestry.com DNA match of “702 centimorgans across 32 DNA segments” indicated a first-cousin relationship with a woman of an unfamiliar name. After months of trying to contact her to find the link between our family lineage, I experienced the shock of my life on 2 November 2019 when her tree connected me to an entry for Sargent Horace Speed II from Newark New Jersey. This shock was both bitter and sweet and helpful for me to better understand my grandmother’s experiences in Texas. I sat for hours staring at a photo of my mother’s biological father, whom she never had the chance to meet. First, I was excited while staring at the resemblance, realizing this was my grandfather. Then, I was angry as the Ancestry.com page helped me better understand why we never met; he was a married man.

He was a successful retired veteran who gave birth to his first child a few years before my mother was born. According to his ancestry tree, my mother has a younger brother born a month after her (February 1954) to his wife. Two years later, Grandpa Speed was stationed in Kenya, where ancestry records indicate that he had a third child with his wife on a military base. I began to wonder if my grandmother was aware of his married status. Was she young, naïve, and impressed with a military uniform? My anger began to grow intensely. My grandmother struggled to raise my mom while her child’s father was traveling the world and exposing my aunts and uncles to the finer things abroad. My mother grew up depressed and suicidal, never fulfilling her desire to go to college and be an accountant, while her father raised his other children with passport stamps and frequent flyer miles. Eventually, I became sad knowing that my mother passed seven years after he did and could have possibly met him. Then I became aware that my cousin may have also discovered our familial connection and decided it would be too harmful to acknowledge the existence of me, my mom, or any evidence of her grandfather’s infidelity with my grandmother. My emotions moved to pride.

My grandmother was resilient and able to move on from whatever experience she had with my mother’s biological dad. In fact, upon his departure she went on with her life and gave birth to my uncle Marvin within two years. I smiled at the thought of her strength and elegance. Giving birth to two babies didn’t cramp her style. At 22, she must have been alluring. I partially believe she was a hopeless romantic. Her ability to move on to Marvin’s dad after being abandoned by a married man displays her ability to choose to desire romance, when some women would have felt hopeless.

4.4. Opportunity Amid Oppression

If knowledge of Texas’ past events such as the riots was not enough, my grandmother had the challenges of her 1950s Texas present. Anti-integration efforts were rampant across the state of Texas after the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas decision, when the Supreme Court invalidated racial segregation in public schools. Approximately 96 miles from Sherman, in Mansfield, Texas, my grandmother gave birth to her second child Deborah in 1954 during a time that local White residents were arming themselves with guns to block Black children from entering schools (

Segregation in America n.d.). After reviewing an article (

Spangler and Robinson 2019) describing the Blackface yearbook photos and racial slurs listed in the University of North Texas yearbooks from 1950 to 1963, I concluded that my grandmother’s decision to leave was one fueled by her desire to escape the antiblack images she was surrounded by, as well as an optimism that California would be void of the White supremacist structures she felt could prevent her from giving her three young children a better life.

More than 6 million other African Americans from the rural South were also inspired to relocate to cities in the North, Midwest, and West during the Great Migration; a period between 1916 and 1970 (

History 2010). The Second World War and the need for wartime equipment labor motivated many Blacks to move west for employment (

Kopf 2016). The Los Angeles area needed labor to fill contracts for automobiles and steel, but these economic opportunities came with racial workplace discrimination that confined Blacks to unskilled positions at work and left them living in restrictive and segregated neighborhoods in the community. There were approximately 70,000 African Americans living in Los Angeles in 1940, 40% of whom were born in Oklahoma, Louisiana, or Texas (

Kopf 2016). It is likely that the successful relocation of other Blacks from the Sherman, Texas, area inspired my grandmother to pack up and travel the fourteen-hundred-mile distance west across the historic Route 66; a U.S. highway with scarce accommodations for African Americans (

Norton 2016). Articles like

The Roots of Route 66 (

Taylor 2016) detail the experiences of Black travelers who were exposed to miles of White supremacy and racism while heading westward. “Although there were no formal segregation laws on the books in California, both Glendale and Culver City were sundown towns and the sun-kissed beaches of Santa Monica were segregated” (

Taylor 2016, p. 16). Family members and I estimate my grandmother’s relocation to have occurred between 1958 and 1959. I can imagine Eula traveling by car with three small children (between 2 and 8 years of age) from Texas to California with a

Greenbook (a travel guide for Black people) in her possession, hope in her heart, and a prayer in her mouth.

5. A California Dream

The move from Texas was the first of many moves my grandmother and her oldest three children would experience. She relocated to California, secured an apartment with her savings, and started working at a barbeque restaurant. At the restaurant, she worked as a cashier occasionally but preferred waiting tables because of the tips. It wasn’t the new opportunity she thought she would obtain, but it helped her pay the bills.

Collins (

2000) establishes the need to challenge the constructs of work and family that deviate Black women’s family and work patterns from those ascribed to the traditional family ideals. Collins describes the work that Black women were able to perform as alienated labor; physically demanding and intellectually deadening types of work associated with Black women’s stats as “mule.” As was common for Black women, due to limited opportunity, my grandmother found herself working long hours beside cooks and dishwashers in the fast food industry.

In 1961 near Anniston, Alabama, a freedom rider bus went up in flames after a firebomb was tossed through the window (

The Clarion-Ledger 2018), nine African-American college students went on trial for sitting in a White city library in Jackson, Mississippi (

Eberhart 2017), and in Southern California my grandmother had given birth to her fourth child, my aunt Renay, at 29 years of age. Not long after arriving in Los Angeles, Eula became involved with a man named Edgar. He previously served in the air force and had a stable income. Shortly after their relationship began, Eula learned about his temper and his vices. The stories lingering around the family talk of domestic violence and physical abuse between Edgar and my grandmother, altercations so fierce, they didn’t even cease during her pregnancy. Despite Edgar’s abusive and womanizing ways, my grandmother stayed with him for several years and even gave birth to my Aunt Loren in December of 1962. Witnessing my grandmother’s abuse from Renay and Loren’s father negatively impacted my Uncle Marvin’s relationship with his mother. I assume that my mother and Aunt Vanessa felt similarly growing up in a household where their mother was physically abused by a man who provided minimal financial assistance and demonstrated negative fatherly traits.

A lot of Black feminist scholars have addressed the patriarchal nature of Black male–female relationships, which they believe have been validated by the Black church and biblical teachings (

Simien 2004). Maybe it was a combination of a religious upbringing and the examples set by Eula’s parents and grandparents, that influenced her habit of inviting men to lead her household. Like many Black women in the United States who were subject to multiple burdens, Eula worked, bore and reared children, and endured the frustration-born violence brought on by frequently under- and/or unemployed mates (

Hine 1989).

I asked my Aunt Loren about her childhood with Eula.

“It was a decent childhood. Were there hugs and kisses, yes…more so when we were children than when we were older... but if you are asking if there were unnecessary whippings and verbal abuse, yes that happened too. I remember she would get mad at me and say you are evil just like your father. You act just like him.”

It appeared that my aunt was attempting to present a neutral assessment of her relationship with my grandmother. Maybe she thought she would negatively influence my perception of Eula. In the end, she admitted she felt Aunt Renay received better treatment from Grandma than she did, likely due to guilt that she was born with a defect in her neck that most people in the family believed resulted from Eula’s abuse.

“One day momma followed my dad to a woman’s house. She went in and confronted him. I don’t remember if the woman did it, or he did it, but some kind of way she got hit in the head. She came home and you could tell she was really sad. She got in the bathtub and I remember going in there and trying to console her. She just sat there and let me rub her back with the sponge and I tried to tend to her head. It was just me and her in the bathroom and I felt like it was a nice bonding moment.” It is unclear how long my grandmother dealt with Edgar romantically, but Loren recalls she last saw him when she was in the 4th grade. He stopped visiting and eventually they moved.

5.1. So. Cal. Sixties

The 1960s Southern California was completely different than the place I grew up knowing. In 2001, I once skipped school and caught several buses to visit friends in Compton and Gardena. My biggest fears of that afternoon stemmed from thoughts of my mother. If my grandmother traveled to Compton when she arrived in the 1960s, her fears may have been the result of seeing White mobs in the area directing bombs, shots, and fires towards the homes of African-American families (

Simpson 2012). Housing shortages due to the influx of the

Great Migration inspired real estate companies like Davenport Builders to build on the undeveloped land that became Compton. This area was initially exclusively White due to racially restrictive covenants keeping people of color from living in predominately White areas (

Behrens 2011).

Jones-Correa (

2000) describes covenants as private agreements barring non-Caucasians from occupying or owning property; a “key element in the segregationist policies in the early twentieth-century United States” (541).

Racially restrictive covenants were adopted prior to World War II, and perpetuated by the practices of real estate agents, law-enforcement agencies and civic leaders (

Feder-Haugabook 2017), who made their imposition a central part of their practices. Covenants, blockbusting, White flight, and redlining contributed to the structural inequalities that made it challenging for my grandmother to achieve the home-owning American dream she thought she might be able to obtain in California. Growing up, I was aware that my grandmother and three of my aunts were on Section-8 (a government rental assistance program that pays landlords on behalf of eligible low-income households). Most of my friends, family, and neighbors lived in apartments and sadly, the first time I learned that one of my friend’s parents was a homeowner I was almost an adult. “Wait. Like…your parents actually

own all this?!?” I asked as I stood inside my friend’s dining room. It was then that I realized that government-assisted housing, apartments, and house rentals were common, but not requisite occurrences. My grandmother preferred living in a house over an apartment. Though she arrived and moved in an apartment, she relocated to a house at the first opportunity. She would rent that home until there was an opportunity to rent a bigger home, or a house in a better area, and then she would downsize again when finances were tight, contributing to my aunts’ and uncle’s instability.

The intergenerational consequences generated by my grandmother’s 1960s pre-civil rights move to Southern California are demonstrated through my family’s sluggish progress towards upward mobility. Her westward migration and lifelong sacrifices are likely to bear more fruit for her great-grandchildren than they did for her children and grandchildren. This is not to say fruit wasn’t there; I just don’t know if the fruit was plentiful enough for the weight of the sacrifices. My mother’s children missed out on intimate relationships with their grandparents and extended Texas family. They experienced instability due to my grandmother moving between jobs and relationships, and they were exposed to drugs and violence to a degree they may have been sheltered from in a small-town Texas community full of family. Eula’s children all finished high school on time except Kathleen, who completed her GED (a standardized examination considered an equivalent of the high school diploma), after getting involved with the wrong crowd and dropping out. I am not sure which high school Vanessa graduated from, but Deborah graduated from Manual Arts High School, Marvin from Locke High School, and Renay and Loren from Los Angeles High School. Vanessa did so well she received a scholarship to attend University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) where she obtained a bachelor’s degree in English. Loren spent a few years working after high school, but she eventually took community college classes at Los Angeles Community College and Trade Tech, until she transferred to the California State University, Los Angeles, and obtained a bachelor’s in teaching in 1983. Vanessa’s daughter Nikki was Eula’s first grandchild, and the first to go to college. She attended Pepperdine for two semesters but stopped out due to finances. Renay’s son TJ could have been the next of Eula’s grandchildren to attend school, except school was put on the back burner when he and Mandy experienced homelessness after their mother’s evictions. Through the support of her friends and her church community, Mandy was able to pave a way from junior college to Belhaven University, which, in turn, provided me with the blueprints to be successful at the California State University, Chico, several years later. Though child abuse of a verbal, physical, or neglectful category was experienced by almost all of Eula’s grandchildren, I believe all nine were capable of higher-education success. Mandy and I were just blessed to avoid becoming parents before attending college, and we were able to step away from the family bubble, to enter environments that allowed us to focus on school. As of 2020, more than sixty years after Eula’s arrival in Los Angeles, only two of my relatives have successfully acquired a property in Los Angeles County, and in 2009, Mandy became the first.

5.2. Food Stamp Act

In the 1960s, the federal government’s social service programs such as family assistance, Medicaid and food stamps were implemented with a number of eligibility requirements that had implications on low socioeconomic status American families (

Willis and Clark 2009). The Food Stamp Act of 1964 was passed on 31 January 1964, my mother Deborah’s 10th birthday, when President Johnson requested Congress to pass legislation making the piloted food stamp program permanent (

United States Department of Agriculture 2018). My grandmother was always the primary breadwinner for her family. In addition to the barbeque restaurant and jobs in the fast food industry, my grandma worked at a beauty store helping stylists wash hair. She typically worked multiple part-time jobs, requiring my Aunt Vanessa to be in charge of overseeing her younger siblings while Eula was at work. There were several times between relationships and employment where my grandmother leaned on government sponsored programs for assistance through programs that provided resources such as food stamps.

This research helped me understand that government aid came at a cost that impacted the African-American family structure. One stipulation for receiving support was that families could not have a male age 18 or up living in the household, resulting in fathers being removed from the household in low-socioeconomic status neighborhoods (

Kelley and Colburn 1996). The lack of employment opportunities and increased unemployment for the Black family influenced women’s decision to seek aid and limit their involvement with their children’s fathers for eligibility. My Aunt Loren explained that my grandmother hated it. “It was really like that movie Claudine. You’ve really got to watch it. The worker would come in and really look to make sure men weren’t around. I remember it was a White lady worker who came over and told momma she was deducting money because she saw we had eaten out… I don’t know if it was a pizza box or what it was, but they were so picky and all in your business.”

5.3. Marriage & Mental Health

At 30 years of age, my grandmother had five children under age 12, and I questioned the state of her mental and emotional health. “Momma would have these moments where she would lay in the room with all the lights off listening to Billie Holiday. She would get pissed if you tried to turn em on, so we would let her be,” said Aunt Loren. Similarly to my mother Deborah, who was clinically diagnosed, it appeared that my grandmother struggled with depression. My aunt described it as something she would go through when in or out of a relationship. Weekend drinking, listening to music in the dark, or laying around with limited energy for interaction was something that my aunt said sporadically happened. “I don’t know, but she always worked though. She would have those days, but she got it together enough to go to work,” Loren confirmed. I wondered if her mental health was impacted by the abuse or if the onset of her depression was the by-product of a decade of hardships that decreased her optimism and motivation, making it hard for her to get out of bed.

Loren and Renay weren’t sure what year Eula’s relationship with Edgar dissolved, though I am glad it did. I wish women of color such as my grandmother didn’t have such a reluctance to call the police, contributing to the suppression of domestic violence that Crenshaw describes in

Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color (

Crenshaw 1991). I became emotional thinking about my grandmother’s overall strength. I wish I could say it was a superpower she was given at birth, but the timeline of personal and historical events I reviewed while conducting this research, in combination with the narrative accounts I obtained from relatives, led to a different revelation. Her strength was akin to a callus; a thickening of the outer layer (of skin) developed to protect from damage caused by prolonged rubbing, pressure, and irritation (

Harvard Health Publishing 2015): a prolonged burden that would be brought on by racism and its intersections with other forms of subordination (sexism, classism, etc.) that shaped the experiences of people of color differently than it did many Whites (

Essed 1991).

I would have personally been ready to call it quits by then but not my grandmother. It seemed she had marital dreams too big to be defeated by the romantic misfortunes she experienced. She continued to date, and in August 1971, she got married to John (a man seven years her junior), just three months shy of giving birth to her last child Kathren. Kathren’s dad was thought of as the spouse she loved the most, possibly because she chose to hold on to his last name. A Los Angeles County Divorce certificate demonstrates that their marriage ended a month shy of 4 1/2 years after it began. No one really spoke of why they divorced, but I presume it may have something to do with his inclination for alcohol, financial instability, and my grandmother approaching a point where she lost much of her previously held optimism.

Sometime after Kathren’s birth, my grandmother obtained a job working for the post office. After years of applying for full-time jobs with good benefits and opportunities for upward mobility, she received a life-changing opportunity. This caused her to lean on her oldest daughter Vanessa more for childrearing assistance. Kathren recalled, “I remember Vanessa walking me to school and picking me up. She was like a mom to me because Momma was 40 when she had me. She was always so busy working, it was like she was always coming and going, but she was saving to make sure we had a place to live, trying to get nice furniture for her family. That’s where I get it from. A lot of what momma use to do, having us wakeup, open windows and clean, trying to make the house nice with furniture. I think that’s where I get it.”

My Aunt Kathren works at a hospital as a licensed practical nurse (LPN). On more than one occasion, I witnessed her two daughters whisking through the living room trying to get her ready for work when she overslept. One would iron scrubs, and the other would pack her lunch. I was tickled when her big sister described a similar scene from their childhood. “I can still see momma in that post-office uniform, everyone helping her get ready for work, ironing her clothes, and bringing her car keys.” Loren shared how happy Eula was to have received that post office job. All of the children were happy about it because they knew it meant more stability for her. Unfortunately, it was all blessing before a literal curse.

While most people who knew my grandmother would agree she suffered from untreated mental illness, she was never actually diagnosed. I grew up my whole life assuming that the monthly check she received was similar to what my mother received and called a Disability Check. My grandmother was actually living off of social security. My aunt explained that the eligibility age was a lot younger decades ago, and she believed my grandmother stopped working around 55 years of age. My cousin Mandy reminded me, “Grandma was too stubborn and private for that. Back then it wasn’t common for people to get mental health treatment. She wouldn’t have gone to the doctor.” She was correct, however my grandmother experienced extreme paranoia.

One weekend, my grandmother made me and my cousins lay in the bed as she cut the lights and television off. “I know what they are doing. They are watching us. No. You not gone get me and mines” she would say loudly while looking at the smoke detector. The red flashing light, likely due to a low battery, triggered her into talking about a mysterious they. My cousins and I would laugh and ask, “who is they grandma?”, curious to know if she was referring to monsters or demons, but she would never tell us. What I refer to as a need for mental health and counseling, my Aunt Loren recently described as a “mentally spiritual issue.” Multiple relatives have shared their take on my grandmother’s peculiar ways, and most refer to her time working at the post office.

5.4. Going Postal

I first heard the story in the 1990s, when my Aunt Vanessa and her daughter had fallen on hard times and come to live with my family. She was the oldest of my grandmother’s children and the person who knew the most about Eula pre- and post-Texas. “Momma got blessed with a job at the post office and she was so excited about it she worked extra hard. She was even promoted to fulltime extremely fast,” said my aunt. She went on to explain that my grandmother had issues with some women coworkers who were from the Louisiana area. “The threatened to put a hex on momma if she kept coming for their job, and she got so scared she tried to fight evil with evil.” Aunt Vanessa described a huge house with a diverse line of people in front of it. Eula’s sister Mary was unsuccessful at talking her out of going, so she decided to drive her to the location with Vanessa riding in the backseat. Vanessa said her mother stood in that line for a long time, went into the home, and never came out the same.

I only knew my Bible-reading grandmother, so it was really hard for me to believe. As I got older and learned more about ritualistic practices associated with various cultures and places in the South, it gave me the lens to understand my grandmother’s strong reaction to people from certain geographical locations. When Loren told my grandmother that her fiancé had family from Louisiana, she looked fearful and said, “oh no. I know what they do.” I recently came to learn the additional pieces to the puzzle. Kathren spoke of a scary man from her childhood who had a long beard, a weird look, and who would come over to the house. Kathren spoke of her initial denial. “I was young, and no one really told me what was happening. We kids had to go to the other room. I just knew they would be cooking stuff with a lot of different smells but there was never any food to eat when he left.” Eula’s cousin Sam confirmed it nonchalantly. “Oh year. Tootsie was into all that ole voodoo stuff.” Loren said she believed Eula’s paranoia kicked in after she submerged herself into a life of black magic and witchcraft. In the end, she tried to put it all behind her. She started watching Christian movies, turning on the Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) throughout the day and leaving open bibles around her house. That was the Eula I met. However, relatives paint a picture of someone who tried to control the situations around her with the help of supernatural forces.

It was almost a decade after my grandmother passed, while conducting research for this publication, that I learned of my grandmother’s success with homeownership. The stability that came with the post office job was a blessing in that, approximately 20 years after arriving, she was able to purchase a house in Los Angeles near Ridgely and Labrea. Loren and Kathren confirmed she even got a part-time job to make enough to furnish the place with new furniture. It just so happened that this occurred around a time that things in her relationship with her youngest daughter’s father were going downhill. Cousin Sam said Eula’s jealousy caused her to try and control everything he did, likely pushing him away. I asked Kathren about her father’s relationship with my grandmother. She said he cheated on her a lot and drank up his income. Loren recalled a time where she and Renay started living with my mom Deborah, because Eula took Kathren and went looking for John.

“She left you guys to go find a man!?!” I asked. Loren exhaled slowly and said, “yeah. She loved him.” My grandmother eventually lost the house to foreclosure. Kathren explained the house wasn’t exactly lost, because Eula gave up on it. During a conversation with my aunt, I learned several things. John had also been in the military (army) at some point in his life, making me question if my grandmother had a thing for military men. She explained that men with stable incomes were coveted in the Black community, and during those times it was hard for Black men to find local work. Veterans were frequently arriving west from other states or returning to California after serving in the military. They didn’t believe it was more than coincidental. Eula’s cousin Sam supposed my grandmother felt comfortable with military men because there was an air force base five miles outside of Sherman, Texas, and they grew up seeing soldiers in their town. Perrin Air Force Base was a pilot training airfield that closed down in 1971 (

Perrin Air Force Base Historical Museum n.d.).

I also learned that Eula may have had her hand in my aunt’s lack of communication with John. “I think momma was felt like when it’s over for me, it’s over for everybody.” Kathren shared that she went years without seeing her dad, until she was about 12 and a paternal cousin helped him locate her. John wanted a relationship with his daughter; however, after the divorce, my grandmother prevented it. Kathren got to enjoy her relationship with her father until he passed away shortly after she gave birth to his granddaughter at 19 years of age.

Kathren recalled several “good men” trying to date my grandmother after John left, but she believed my grandmother had just given up; on relationships, work, and optimism. I would like to believe my grandmother found and experienced the one, though it seems like the relationships she invested the most in came with abuse, infidelity, addictions, and financial instability. I am just as proud to know that my grandmother was optimistic enough to give love another try as many times as she did and audacious in her ability to provide for her children when it was time to walk away.

5.5. Rodney King and Beyond

My little sister Jay was born in 1992. Though only six years old, I remember that year distinctly for two reasons: the LA Earthquake with its 7.3 magnitude force and the LA riots, which brought just as much fury. I excitedly watched neighborhood teenagers running down our block, bragging about the free items they had obtained from the corner store. The news showed riots across the city, mini-protests, and looters taking advantage of the opportunity to take possessions from the neighborhood stores during the moments of mayhem. Days after the Rodney King riots, I became more aware of the reasons for the televised anger. I overheard my older cousin talking about it; being a Black man in Los Angeles, knowing that interactions with the police could be just as dangerous as those with local street gangs. Eula couldn’t have predicted her California dream would lead to her children and grandchildren being exposed to so much adversity, but I wondered why she chose to stay three decades after striving to obtain a better life than most would conclude she ever made.

In 1992, she had lived in California for over thirty years. Her children were grown, and she was a grandmother to seven. She was living off of her social security check while two of her daughters (my mom Deborah and my Aunt Renay) were supporting themselves with Supplemental Security Income (SSI), something people in the family referred to as “disability.” Evictions, addictions, food insecurity, housing instability, and child abuse were factors impacting the lives of her children’s children, and she was caught in a cycle of check-into-cash loan advances to cover the monthly debt, her SSI check couldn’t cover.

My grandmother’s relatives in Texas called to share news of their home purchases, highlighting the success of their children who were steadily working in local industrial plants and/or entering college or vocational programs. My grandmother and her children had boasting rights about living near Hollywood, but their reality included struggles to pay rent in a city without rent control, and sorrow brought on by the influx of crack cocaine that started sweeping through and deteriorating low-income communities in the 1980s (

Banks 2010).

By the time I finished high school, my grandmother’s health had significantly deteriorated. She went from needing a walker after having a stroke, to depending on a wheelchair to go significant lengths. The local shopping center near her bungalow on Florence and Vermont catered to those interested in bail bonds, quick loans, manicures, liquor, and Chinese food. This isn’t uncommon for communities of color, where neighborhoods typically have a reduced presence of grocery stores and an increased presence of fast food restaurants (

Taylor 2016). Many Black families hold the sentiment that putting a parent in a nursing home is cruel and disrespectful. There was a period of time, before things went from bad to worse, that I believe a home could have been a positive experience for my grandmother. Before she lost her spunk, I think she would have enjoyed living in a place with adult interaction, bingo, and around-the-clock coffee. I made several jokes to my mother about my grandmother needing a boyfriend, but we both laughed at the thought.

It wasn’t until later, after my grandmother was homebound with high blood pressure, arthritis, glaucoma, high cholesterol and acid reflux after having a stroke, that I realized how lonely she was. She asked me if I could really find a guy on the computer (online dating) and shared that she would be open to meeting a Middle Eastern man. My aunts didn’t believe she said it, but it slightly broke my heart.

6. Walking Tall

Eula arrived in California shortly before Bryan Rumford sponsored the California Fair Housing Act to prohibit racial discrimination by real estate brokers. I have identified numerous historical artifacts that demonstrate the existence of limited employment opportunities, systemic challenges preventing the acquisition of property, and education-system disparities that led to wealth differences for Black families. These all had intergenerational consequences for Eula and her family due to the close relationship between wealth and educational access and opportunity (

May and Sleeter 2010).

Eula and her children’s intersectional identities led to a presence of inextricable layers of racialized subordination based on race, gender, and phenotype, amongst other things (

Crenshaw 1993). The intimate partner violence, income inequality, and housing instability weren’t a match for her tenacity. However, the local gang violence, drugs, lack of affordable housing, and unmet emotional health needs experienced by people of color in Los Angeles, California, caused her children to experience many of the issues she worked hard to avoid (i.e., homelessness, prison sentences, addiction).

When she finally stopped working, and spent time observing the lives her children had begun to lead, it was probably hard to swallow. In the early 2000s, my Aunt Vanessa struggled with joblessness, Marvin was in prison, and Deborah was widowed, depressed, and physically violent with her children. Renay was clinically diagnosed schizophrenic and homeless after multiple evictions, Loren struggled with health issues and Kathren was in a domestic violence relationship with her children’s father. Despite my grandmother’s efforts to work hard and maintain a nice home for her family, several of her children spent years in cycles of housing assistance, medication, food stamps, and disability checks. At that point, Eula directed her focus on frequently visiting and protecting her grandchildren.

I will always cherish the weekends I spent with my cousins at my grandmother’s. Unaware of her trials and tribulations, we were completely ignorant of the woman she was before she became “grandma.” My father’s passing triggered my mother into a depression that Eula would often try and shield me from. She would catch a Metrorail and two buses to come and get me so that I could go back with her to her studio apartment in the Valley. From the corner store on Hobart and Venice, I could see her walking from the bus stop; black slacks, cream satin blouse, burgundy lipstick, wig, and briefcase. She refused to leave the house without looking what she called “dignified,” and my dignified grandma is the Eula I chose to remember in my thoughts.

She passed in 2011. After several hospitalizations for strokes, she was diagnosed with binary cancer of the bowel duct. My last physical visit with her on a trip home from graduate school, I was saddened by how ill and helpless she looked. “Granny just can’t keep nothing down,” she said when I asked about the untouched bowl of tuna and crackers siting on her white nightstand. She tried to make a usual joke and ask me when I was going to perm and color her hair. It was humorous because no one ever saw her real hair under her wigs. Her hair consisted of sporadically placed, thin, salt and pepper colored strands that ranged from a few centimeters to three inches long at best.

She hadn’t been diagnosed during our last visit, but looking back, I am fairly confident the cancer had set in. I believe that years of working low-wage jobs that lacked health, and discriminatory practices and expenses Black people associated with hospitals, conditioned her to avoid doctors even when she had Medicare. My aunts could convince her to go when she was in extreme pain, or needed a checkup for medication prescription refills; however, the challenge of getting her and her wheelchair to her appointments was as challenging in a vehicle as it was traveling by city bus.

I was confused and saddened looking at my grandmother; sad she was alone, in a roach-infested government-subsidized apartment, unable to walk, wearing depends, and struggling to pronounce her words without her teeth, which were inside of a tall glass of water on the nightstand. Confused by her ability to tune it all out, and laugh while we spoke about hair, I used the excuse of expensive student loans as I denied her request for me to “go run and buy granny some Newport’s and a Pepsi.” Privilege, power, and oppression play a big role in the health disparities Black women face in this country (

Taylor 2016), but the “inside” ideas that exist in the hidden space of their consciousness allows them to cope (

Collins 2000). In that moment, when I struggled to ignore the despair of our surroundings, my grandmother was able to utilize a skill she, and Black women in America, develop over the course of their lives; the ability to transcend the confines of oppressions.

7. Conclusions

My grandmother Eula, a pre-civil rights movement born African-American single parent of three young children, demonstrated extreme tenacity in her journey to move her family west. In a time where opportunities were slim, and heartache and disappointment had been consistent, she joined the wave of Blacks who migrated to California with hopes of better opportunities. Knowing the experiences of Eula, my mother, and my recently deceased uncle, it would be easy to offer a negative critique of my grandmother’s decision to settle in Los Angeles. Prior to conducting this research, I believed she should have returned to Texas to ensure that her children and grandchildren were in geographical proximity to family and potential familial support. Today, my newly obtained knowledge of Texas as it existed for an unwed Black woman in the 1950s, coupled with personal experience being the firstborn child (e.g., my ability to sympathize with the domestic pressures likely put on her), and recent Ancestry.com findings, I have concluded that Eula Mae did the best she could considering the existing overt and covert racism and sexism that influenced the American social systems she experienced.

She walked tall on her journey, and managed to keep her children alive and well, while literally and figuratively navigating Southern California and the opportunities she sought. She survived underemployment, evictions, foreclosure, low-income neighborhoods, untreated mental health needs, domestic violence, and financial strain, because she was hardworking, stubborn, and resilient. It is because of her that my cousin Mandy and I were able to obtain multiple degrees. It is because of Eula that cousin Mandy and my Aunt Loren were able to purchase a home in coveted areas of Los Angeles. My grandmother followed her heart thousands of miles across Route 66 and inadvertently faced decades of oppression to the best of her ability. It is because of her valiant efforts and decision not to give up that her grandchildren and great-grandchildren are afforded a new normal.