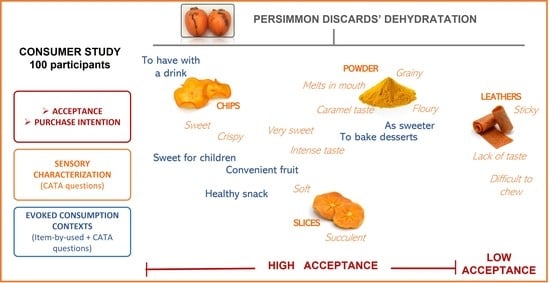

Acceptance, Sensory Characterization and Consumption Contexts for Dehydrated Persimmon Slices, Chips, Leathers and Powder: A Consumer Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Slices

2.1.2. Chips

2.1.3. Leathers

2.1.4. Powder

2.2. Consumer Study

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Consumer Interest in Each Persimmon-Derived Product, Acceptance and Sensory Characterization

3.2. Consumption Contexts for Fresh Fruit and Products

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MAPA. Avances de Datos de Frutales no Cítricos y Frutales Secos. 2021. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/estadistica/temas/estadisticas-agrarias/agricultura/superficies-producciones-anuales-cultivos/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- FAOSTAT. World Food and Agricultural Organization Data of Statistics. Food Agric. Organ. 2022. Persimmon Production in the World. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Fernández-Zamudio, M.A.; Barco, H.; Schneider, F. Direct measurement of mass and economic harvest and post-harvest losses in Spanish persimmon primary production. Agriculture 2020, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, E.; Pons-Gómez, A.; Besada, C. Physico-chemical and microstructural changes during the drying of persimmons with different disorders. Consumer acceptance of dried slices as a criterion to valorise discards. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cárcel, J.A.; García-Pérez, J.V.; Sanjuán, N.; Mulet, A. Influence of pre-treatment and storage temperature on the evolution of the colour of dried persimmon. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milczarek, R.R.; Woods, R.D.; LaFond, S.I.; Breksa, A.P.; Preece, J.E.; Smith, J.L.; Vilches, A.M. Synthesis of descriptive sensory attributes and hedonic rankings of dried persimmon (Diospyros kaki sp.). Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Khalifa, I.; Hu, L.; Zhu, W.; Li, J.; Li, K.; Li, C. Influence of three different drying techniques on persimmon chips’ characteristics: A comparison study among hot-air, combined hot-air-microwave, and vacuum-freeze drying techniques. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 118, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.M.; Hernando, I.; Moraga, G. Influence of ripening stage and de-astringency treatment on the production of dehydrated persimmon snacks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Pulido, B.; Bas-Bellver, C.; Betoret, N.; Barrera, C.; Seguí, L. Valorization of vegetable fresh-processing residues as functional powdered ingredients. A review on the potential impact of pretreatments and drying methods on bioactive compounds and their bioaccessibility. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 654313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseininejad, S.; Larrea, V.; Moraga, G.; Hernando, I. Evaluation of the bioactive compounds, and physicochemical and sensory properties of gluten-free muffins enriched with persimmon ‘Rojo brillante’ flour. Foods 2022, 11, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, D.; Dalgıç, A.C. Production and preference mapping of persimmon fruit leather: An optimization study by Box–Behnken. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, e12899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.H.; Ragab, M.; Siliha, H.A.I.; Haridy, L.A. Physicochemical, microbiological and sensory characteristics of persimmon fruit leather. Zagazig J. Agric. Res. 2018, 45, 2071–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancón, P.; Fernández-Serrano, P.; Besada, C. Consumer perception of situational appropriateness for fresh, dehydrated and fresh-cut fruits. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D. Situational appropriateness in food-oriented consumer research: Concept, method, and applications. In The Effects of Environment on Product Design and Evaluation; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novillo, P.; Salvador, A.; Navarro, P.; Besada, C. Involvement of the redox system in chilling injury and its alleviation by 1-methylcyclopropene in ‘Rojo brillante’ persimmon. HortScience 2015, 50, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilkanat, N.; Savlak, N. Utilization of persimmon powder in gluten-free cakes and determination of their physical, chemical, functional and sensory properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, E.; Van Trijp, H.C.M.; Luning, P. Consumer research in the early stages of new product development: A critical review of methods and techniques. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Giacalone, D.; Roigard, C.M.; Pineau, B.; Vidal, L.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Investigation of bias of hedonic scores when co-eliciting product attribute information using CATA questions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillion, L.; Kilcast, D. Consumer perception of crispness and crunchiness in fruits and vegetables. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, G.; Saravanan, S.; Galvão, M.; Santos Leite Neta, M.; Sandes, R.; Mujumdar, A.; Narain, N. Comparative evaluation of physical properties and aroma profile of carrot slices subjected to hot air and freeze drying. Dry. Technol. 2016, 35, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, V.; Cinquanta, L.; Vella, F.; Niro, S.; Panfili, G.; Metallo, A.; Cuccurullo, G.; Corona, O. Evolution of carotenoids, sensory profiles and volatile compounds in microwave-dried fruits of three different loquat cultivars (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.). Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Jesionkowska, K.; Symoneaux, R.; Konopacka, D.; Snoek, H. Perceptions of the health and convenience characteristics of fresh and dried fruits. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Taufik, D.; Raaijmakers, I.; Reinders, M.J. Motive-based consumer segments and their fruit and vegetable consumption in several contexts. Food Res. Int. 2020, 127, 108731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfilova, O.V.; Akishin, D.V.; Vinnitskaya, V.F.; Danilin, S.I.; Olikainen, O.V. Use of vegetable and fruit powder in the production technology of functional food snacks. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 548, 082071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvola, A.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Dean, M.; Vassallo, M.; Winkelmann, M.; Claupein, E.; Saba, A.; Shepherd, R. Consumers beliefs about whole and refined grain products in the UK, Italy and Finland. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofton, E.C.; Scannell, A.G. Snack foods from brewing waste: Consumer-led approach to developing sustainable snack options. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3899–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NO Fresh– YES Snacks (%) | NO Fresh– YES Powder (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Breakfast or lunch | 8 | 4 |

| Dessert at lunch or dinner | 2 | 0 |

| School lunchbox | 20 | 0 |

| Healthy alternative snack | 49 | 3 |

| Ingredient for cooking desserts | 32 | 50 |

| Ingredient in dishes | 26 | 25 |

| Sweetening hot drinks | 19 | 61 |

| Sweetening yoghurt | 20 | 44 |

| Prepare juices or smoothies | 4 | 28 |

| Snack at home | 33 | 2 |

| Snack when not at home | 49 | 0 |

| Sweet and healthy snack | 47 | 1 |

| To eat when having a drink | 37 | 3 |

| Convenient and quick way to eat fruit | 30 | 1 |

| Healthy alternative to sweets for children | 54 | 0 |

| Picnic or trip | 31 | 0 |

| Practice sport | 24 | 0 |

| Breakfast or lunch | 8 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castillo, M.; Pons-Gómez, A.; Albert-Sidro, C.; Delpozo, B.; Besada, C. Acceptance, Sensory Characterization and Consumption Contexts for Dehydrated Persimmon Slices, Chips, Leathers and Powder: A Consumer Study. Foods 2023, 12, 1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12101966

Castillo M, Pons-Gómez A, Albert-Sidro C, Delpozo B, Besada C. Acceptance, Sensory Characterization and Consumption Contexts for Dehydrated Persimmon Slices, Chips, Leathers and Powder: A Consumer Study. Foods. 2023; 12(10):1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12101966

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo, Marina, Ana Pons-Gómez, Carlos Albert-Sidro, Barbara Delpozo, and Cristina Besada. 2023. "Acceptance, Sensory Characterization and Consumption Contexts for Dehydrated Persimmon Slices, Chips, Leathers and Powder: A Consumer Study" Foods 12, no. 10: 1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12101966