Study of Amine Functionalized Mesoporous Carbon as CO2 Storage Materials

Abstract

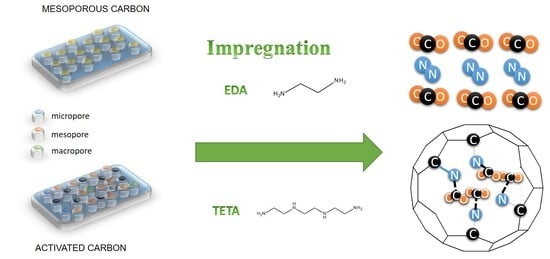

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Mesoporous Carbon

2.3. Modification of Carbon Materials with Amine-Functional Groups

2.4. Characterization

2.5. Adsorption of CO2

3. Results

3.1. Adsorbent Characterization

3.1.1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

3.1.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3.1.3. CO2 Adsorption Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Houshmand, A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Shafeeyan, M.S. Exploring potential methods for anchoring amine groups on the surface of activated carbon for CO2 adsorption. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1098–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Guo, Q. Development of hybrid amine-functionalized MCM-41 sorbents for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, K.; Krozer, Y.; Filatova, T. Trade-offs between electrification and climate change mitigation: An analysis of the Java-Bali power system in Indonesia. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 1020–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theo, W.L.; Lim, J.S.; Hashim, H.; Mustaffa, A.A.; Ho, W.S. Review of pre-combustion capture and ionic liquid in carbon capture and storage. Appl. Energy 2016, 183, 1633–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Okolie, J.A.; Abdelrasoul, A.; Niu, C.; Dalai, A.K. Review of post-combustion carbon dioxide capture technologies using activated carbon. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 83, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Shi, H.; Lee, J.Y. CO2 absorption mechanism in amine solvents and enhancement of CO2 capture capacity in blended amine solvent. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control. 2016, 45, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lawal, A.; Stephenson, P.; Sidders, J.; Ramshaw, C. Post-combustion CO2 capture with chemical absorption: A state-of-the-art review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 1609–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, C.H.; Huang, C.H.; Tan, C.S. A review of CO2 capture by absorption and adsorption. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lakhi, K.S.; Cha, W.S.; Joseph, S.; Wood, B.J.; Aldeyab, S.S.; Lawrence, G.; Choy, J.H.; Vinu, A. Cage type mesoporous carbon nitride with large mesopores for CO2 capture. Catal. Today 2015, 243, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Arencibia, A.; Calleja, G.; Sanz, R. Tuning the textural properties of HMS mesoporous silica. Functionalization towards CO2 adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 260, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, C.A.; Helal, A.; Al-Maythalony, B.A.; Yamani, Z.H.; Cordova, K.E.; Yaghi, O.M. The chemistry of metal-organic frameworks for CO2 capture, regeneration and conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Zhu, M.; Fu, Y.; Huang, Y.X.; Tao, Z.C.; Li, W.L. Using 13X, LiX, and LiPdAgX zeolites for CO2 capture from post-combustion flue gas. Appl. Energy 2017, 191, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pozuelo, G.; Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Arencibia, A.; Pizarro, P.; Sanz, R.; Serrano, D.P. CO2 adsorption on amine-functionalized clays. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 282, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.L.; Mafra, L.; Guil, J.M.; Pires, J.; Rocha, J. Adsorption and activation of CO2 by amine-modified nanoporous materials studied by solid-state NMR and 13CO2 adsorption. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Qiao, W.; Long, D.; Ling, L. Carbon dioxide capture using polyethylenimine-loaded mesoporous carbons. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ramli, A.; Yusup, S. CO2 adsorption study on primary, secondary and tertiary amine functionalized Si-MCM-41. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 51, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, B.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Z. Hierarchically Mesoporous o-Hydroxyazobenzene Polymers: Synthesis and Their Applications in CO2 Capture and Conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 128, 9837–9841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Parshetti, G.K.; Balasubramanian, R. Post-combustion CO2 capture using mesoporous TiO2/graphene oxide nanocomposites. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 263, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, T.; Song, Y.; Che, S.; Fang, X.; Zhou, L. Amine-functionalized mesoporous ZSM-5 zeolite adsorbents for carbon dioxide capture. Solid State Sci. 2017, 73, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Kim, S.; Yoon, M.; Bae, T.H. Hierarchical Zeolites with Amine-Functionalized Mesoporous Domains for Carbon Dioxide Capture. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Chai, S.H.; Mayes, R.T.; Tan, S.; Jones, C.W.; Dai, S. Significantly increasing porosity of mesoporous carbon by NaNH2 activation for enhanced CO2 adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 230, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schott, J.A.; Wu, Z.; Dai, S.; Li, M.; Huang, K.; Schott, J.A. Effect of metal oxides modification on CO2 adsorption performance over mesoporous carbon. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 230, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adeniran, B.; Mokaya, R. Is N-Doping in Porous Carbons Beneficial for CO2 Storage? Experimental Demonstration of the Relative Effects of Pore Size and N-Doping. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, K.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, L. Highly selective CO2 capture by nitrogen enriched porous carbons. Carbon 2015, 92, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zou, B.; Hu, C.; Cao, M. Nitrogen-doped porous carbon nanofiber webs for efficient CO2 capture and conversion. Carbon 2016, 99, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, I.; Aniruddha, R.; Malik, S. Carbon capture using amine modified porous carbons derived from starch (Starbons®). SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Senkovska, I.; Oschatz, M.; Lohe, M.R.; Borchardt, L.; Heerwig, A.; Liu, Q.; Kaskel, S. Highly porous nitrogen-doped polyimine-based carbons with adjustable microstructures for CO2 capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10951–10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-L.; Zhang, J.-B.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Zhong, F.-Y.; Wu, P.-K.; Huang, K.; Fan, J.-P.; Liu, F. Chitosan-derived mesoporous carbon with ultrahigh pore volume for amine impregnation and highly efficient CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Jones, C.W. Adsorbent Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Large Anthropogenic Point Sources. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 796–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardhyarini, N.; Krisnandi, Y.K. Carbon dioxide capture by activated methyl diethanol amine impregnated mesoporous carbon. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1862, 30090. [Google Scholar]

- Górka, J.; Zawiślak, A.; Choma, J.; Jaroniec, M. Adsorption and structural properties of soft-templated mesoporous carbons obtained by carbonization at different temperatures and KOH activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 5187–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, W.W.; Wibowo, A.H.; Astuti, S.; Pamungkas, A.Z.; Krisnandi, Y.K. Fabrication of hybrid coating material of polypropylene itaconate containing MOF-5 for CO2 capture. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 115, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Lee, H.I.; Yie, J.E.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, J.M. Ordered mesoporous carbons: Implication of surface chemistry, pore structure and adsorption of methyl mercaptan. Carbon 2005, 43, 1868–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingombe, P.; Saha, B.; Wakeman, R. Surface modification and characterisation of a coal-based activated carbon. Carbon 2005, 43, 3132–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.; Wu, Z.; Fan, J.; Zhang, W.-X.; Zhao, D. Amino-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon for the separation of toxic microcystin-LR. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19168–19176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.; Aranovich, G. A new classification of isotherms for Gibbs adsorption of gases on solids. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1999, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Lee, M.-G.; Shafeeyan, M.S. Carbon Dioxide Capture with Amine-Grafted Activated Carbon. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 223, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Merz, K.M. Theoretical investigation of the CO2 + OH-→HCO3- reaction in the gas and aqueous phases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 9640–9647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Lin, R.; He, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, S. Rapid synthesis of solid amine composites based on short mesochannel SBA-15 for CO2 capture. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 185, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutyala, S.; Jonnalagadda, M.; Mitta, H.; Gundeboyina, R. CO2 capture and adsorption kinetic study of amine-modified MIL-101 (Cr). Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 143, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, N.; Hu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J. Polyethyleneimine entwine thermally-treated Zn/Co zeolitic imidazolate frameworks to enhance CO2 adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 364, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, M.; Yao, L.; Qiao, W.; Long, D.; Ling, L. Direct Capture of Low-Concentration CO2 on Mesoporous Carbon-Supported Solid Amine Adsorbents at Ambient Temperature. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 5319–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.H.; Lestari, W.W.; Teteki, F.J.; Krisnandi, Y.K.; Suratman, A. A preliminary study of functional coating material of polypropylene itaconate incorporated with [Cu 3 (BTC) 2 ] MOF as CO2 adsorbent. Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 101, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Mitome, T.; Egashira, Y.; Nishiyama, N. Phase control of ordered mesoporous carbon synthesized by a soft-templating method. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 384, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Zimmerman, J.B. The United Nations sustainability goals: How can sustainable chemistry contribute? Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 13, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | SBET a (m2 g−1) | Sext b (Mesopore Area) (m2 g−1) | Smic b (Micropore Area) (m2 g−1) | Vtot c (Total Pore Volume) (cm3 g−1) | Vmicro b (Micropore Volume) (cm3 g−1) | Vmeso (Mesopore Volume) (cm3 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | 391.11 | 295.08 | 96.02 | 0.738 | 0.045 | 0.693 |

| MC-EDA49 | 290.29 | 262.40 | 27.89 | 0.637 | 0.01 | 0.627 |

| MC-EDA100 | 163.19 | 163.19 | 0 | 0.301 | 0 | 0.301 |

| MC-TETA30 | 161.30 | 161.30 | 0 | 0.407 | 0.06 | 0.347 |

| MC-TETA52 | 68.35 | 68.35 | 0 | 0.107 | 0 | 0.107 |

| AC | 518.90 | 268.20 | 250.70 | 0.491 | 0.234 | 0.257 |

| AC-TETA14 | 17.83 | 17.83 | 0 | 0.082 | 0.0067 | 0.0753 |

| AC-TETA21 | 17.27 | 17.27 | 0 | 0.079 | 0.0062 | 0.0728 |

| Material | Temperature (°C) | Adsorption Capacity (mmol/g) | Quantification Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBA15-HBP(DETA) | 30 | 0.41 | Gas Chromatography | [41] |

| SBA15-HBP(TETA) | 30 | 0.68 | Gas Chromatography | [41] |

| ZSM-5(TEPA) | 100 | 1.8 | Gravimetric | [19] |

| Zn/Co-ZIF(PEI40) | 25 | 1.82 | Microbalance | [43] |

| SBA15-HBP(TEPA) | 30 | 2.11 | Gas Chromatography | [41] |

| MCM-41(TEPA60) | 70 | 2.45 | Gas Chromatography | [2] |

| MC-PEI70 | 25 | 2.82 | Gas Chromatography | [44] |

| SBA-15-PEI(600) | 30 | 3.2 | Gas Chromatography | [41] |

| MCM-41-APTS30-TEPA40 | 70 | 3.45 | Gas Chromatography | [2] |

| MIL101-(Cr)-PEI70 | room temperature | 3.81 | Gas Chromatography | [42] |

| MOF-5 | room temperature | 5.46 | Titration * | [32] |

| MC-PEI65 | 75 | 4.12 | Gas Chromatography | [15] |

| MC-TETA30 | room temperature | 11.24 | Titration * | This work |

| MC-EDA49 | room temperature | 19.68 | Titration * | This work |

| [Cu3(BTC)2] | room temperature | 234.26 | Titration * | [45] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faisal, M.; Pamungkas, A.Z.; Krisnandi, Y.K. Study of Amine Functionalized Mesoporous Carbon as CO2 Storage Materials. Processes 2021, 9, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9030456

Faisal M, Pamungkas AZ, Krisnandi YK. Study of Amine Functionalized Mesoporous Carbon as CO2 Storage Materials. Processes. 2021; 9(3):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9030456

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaisal, Muhamad, Afif Zulfikar Pamungkas, and Yuni Krisyuningsih Krisnandi. 2021. "Study of Amine Functionalized Mesoporous Carbon as CO2 Storage Materials" Processes 9, no. 3: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9030456