Development of a New Hyaluronic Acid Based Redox-Responsive Nanohydrogel for the Encapsulation of Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Immunotherapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Thiolated Hyaluronic Acid

2.3. Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H-NMR)

2.4. Oncolytic Viruses

2.5. Formulation of Empty/OV-Loaded Nanohydrogel

2.6. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.8. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

2.9. Raman Spectroscopy

2.10. Redox Sensitive and Stability Test of the Nanohydrogel

2.11. Cell Culture

2.12. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

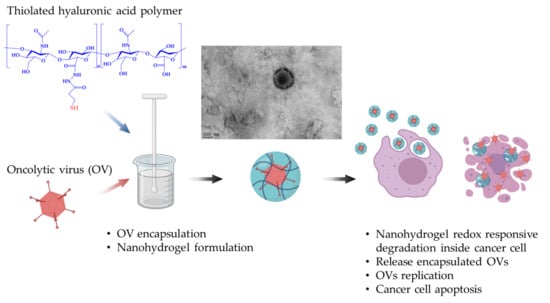

3.1. Encapsulation of Oncolytic Adenovirus into the Nanohydrogel

3.2. The Nanohydrogel Is Successfully Cross-Linked by Disulfide Bonds

3.3. The Nanohydrogel Possesses Stability and Redox Responsiveness

3.4. Oncolytic Activity of OV-Loaded Nanohydrogels

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Ames, F.; Buzdar, A.U.; Kau, S.; McNeese, M.; Paulus, D.; Hug, V.; Holmes, F.; Romsdahl, M.; Fraschini, G. Management of stage III primary breast cancer with primary chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy. Cancer 1988, 62, 2507–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, W.A., III; Liu, P.; Barrett, R.J.; Stock, R.J.; Monk, B.J.; Berek, J.S.; Souhami, L.; Grigsby, P.; Gordon, W., Jr.; Alberts, D.S. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 1606–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosset, J.-F.; Collette, L.; Calais, G.; Mineur, L.; Maingon, P.; Radosevic-Jelic, L.; Daban, A.; Bardet, E.; Beny, A.; Ollier, J.-C. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Fang, H. Clinical trials with oncolytic adenovirus in China. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2007, 7, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghi, M.; Martuza, R.L. Oncolytic viral therapies–the clinical experience. Oncogene 2005, 24, 7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, T.-C.; Kirn, D. Systemic efficacy with oncolytic virus therapeutics: Clinical proof-of-concept and future directions. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hotte, S.J.; Lorence, R.M.; Hirte, H.W.; Polawski, S.R.; Bamat, M.K.; O’Neil, J.D.; Roberts, M.S.; Groene, W.S.; Major, P.P. An Optimized Clinical Regimen for the Oncolytic Virus PV701. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, T.-C.; Galanis, E.; Kirn, D. Clinical trial results with oncolytic virotherapy: A century of promise, a decade of progress. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2007, 4, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J. RNA viruses as virotherapy agents. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002, 9, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.C.; Lichty, B.; Stojdl, D. Getting oncolytic virus therapies off the ground. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebert, O.; Shinozaki, K.; Huang, T.-G.; Savontaus, M.J.; García-Sastre, A.; Woo, S.L. Oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus for treatment of orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma in immune-competent rats. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3605–3611. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Yun, C.O.; Kim, S.W. Polymeric oncolytic adenovirus for cancer gene therapy. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mansour, M.; Palese, P.; Zamarin, D. Oncolytic specificity of Newcastle disease virus is mediated by selectivity for apoptosis-resistant cells. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 6015–6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, C.; Paraskevakou, G.; Iankov, I.; Giannini, C.; Schroeder, M.; Sarkaria, J.; Puri, R.K.; Russell, S.J.; Galanis, E. Interleukin-13 displaying retargeted oncolytic measles virus strains have significant activity against gliomas with improved specificity. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, J.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. First oncolytic virus approved for melanoma immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1115641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eissa, I.R.; Bustos-Villalobos, I.; Ichinose, T.; Matsumura, S.; Naoe, Y.; Miyajima, N.; Morimoto, D.; Mukoyama, N.; Zhiwen, W.; Tanaka, M. The current status and future prospects of oncolytic viruses in clinical trials against melanoma, glioma, pancreatic, and breast cancers. Cancers 2018, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Hu, W.; Liang, M.; Chen, S.; Hu, F.; Chu, D. A phase I trial of intratumoral administration of recombinant oncolytic adenovirus overexpressing HSP70 in advanced solid tumor patients. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, T.-C.; Kirn, D. Gene therapy progress and prospects cancer: Oncolytic viruses. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alemany, R. Cancer selective adenoviruses. Mol. Aspects Med. 2007, 28, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokisalmi, P.; Pesonen, S.; Escutenaire, S.; Särkioja, M.; Raki, M.; Cerullo, V.; Laasonen, L.; Alemany, R.; Rojas, J.; Cascallo, M. Oncolytic adenovirus ICOVIR-7 in patients with advanced and refractory solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3035–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boquet, M.P.; Wonganan, P.; Dekker, J.D.; Croyle, M.A. Influence of method of systemic administration of adenovirus on virus-mediated toxicity: Focus on mortality, virus distribution, and drug metabolism. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2008, 58, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yao, X.; Yoshioka, Y.; Morishige, T.; Eto, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Okada, Y.; Mizuguchi, H.; Mukai, Y.; Okada, N.; Nakagawa, S. Systemic administration of a PEGylated adenovirus vector with a cancer-specific promoter is effective in a mouse model of metastasis. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pesonen, S.; Nokisalmi, P.; Escutenaire, S.; Särkioja, M.; Raki, M.; Cerullo, V.; Kangasniemi, L.; Laasonen, L.; Ribacka, C.; Guse, K. Prolonged systemic circulation of chimeric oncolytic adenovirus Ad5/3-Cox2L-D24 in patients with metastatic and refractory solid tumors. Gene Ther. 2010, 17, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Curiel, D.T. Current issues and future directions of oncolytic adenoviruses. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, R.; Suzuki, K.; Curiel, D.T. Blood clearance rates of adenovirus type 5 in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 2605–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, C.R.; Lachapelle, A.; Delgado, C.; Parkes, V.; Wadsworth, S.C.; Smith, A.E.; Francis, G.E. PEGylation of adenovirus with retention of infectivity and protection from neutralizing antibody in vitro and in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croyle, M.A.; Chirmule, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wilson, J.M. “Stealth” adenoviruses blunt cell-mediated and humoral immune responses against the virus and allow for significant gene expression upon readministration in the lung. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 4792–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.-H.; Kasala, D.; Na, Y.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, S.W.; Jeong, J.H.; Yun, C.-O. Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of an adenovirus-PEI-bile-acid complex in tumors with low coxsackie and adenovirus receptor expression. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5505–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.-A.; Yun, C.-O. Current advances in adenovirus nanocomplexes: More specificity and less immunogenicity. BMB Rep. 2010, 43, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mok, H.; Park, J.W.; Park, T.G. Enhanced intracellular delivery of quantum dot and adenovirus nanoparticles triggered by acidic pH via surface charge reversal. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008, 19, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, C.; Jenkins, G.; Hilfinger, J.; Davidson, B. Poly-L-lysine improves gene transfer with adenovirus formulated in PLGA microspheres. Gene Ther. 1999, 6, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.J.; Kang, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lim, Y.-b.; Chung, H.W. Comparative studies on the genotoxicity and cytotoxicity of polymeric gene carriers polyethylenimine (PEI) and polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer in Jurkat T-cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 33, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Cheng, W.; Teo, P.Y.; Engler, A.C.; Coady, D.J.; Hedrick, J.L.; Yang, Y.Y. Mitigated cytotoxicity and tremendously enhanced gene transfection efficiency of PEI through facile one-step carbamate modification. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013, 2, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semashko, V.V.; Pudovkin, M.S.; Cefalas, A.-C.; Zelenikhin, P.V.; Gavriil, V.E.; Nizamutdinov, A.S.; Kollia, Z.; Ferraro, A.; Sarantopoulou, E. Tiny rare-earth fluoride nanoparticles activate tumour cell growth via electrical polar interactions. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, S.-I.; Drummen, G.P.; Kuroda, M. Focus on extracellular vesicles: Development of extracellular vesicle-based therapeutic systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aoyama, K.; Kuroda, S.; Morihiro, T.; Kanaya, N.; Kubota, T.; Kakiuchi, Y.; Kikuchi, S.; Nishizaki, M.; Kagawa, S.; Tazawa, H. Liposome-encapsulated plasmid DNA of telomerase-specific oncolytic adenovirus with stealth effect on the immune system. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Record, M.; Silvente-Poirot, S.; Poirot, M.; Wakelam, M.J. Extracellular vesicles: Lipids as key components of their biogenesis and functions. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dass, C.R.; Choong, P.F. Selective gene delivery for cancer therapy using cationic liposomes: In vivo proof of applicability. J. Control. Release 2006, 113, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, M.; Villa, A.; Rizzi, N.; Kuryk, L.; Rinner, B.; Cerullo, V.; Yliperttula, M.; Mazzaferro, V.; Ciana, P. Extracellular vesicles enhance the targeted delivery of immunogenic oncolytic adenovirus and paclitaxel in immunocompetent mice. J. Control. Release 2019, 294, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, M.; Saari, H.; Somersalo, P.; Crescenti, D.; Kuryk, L.; Aksela, L.; Capasso, C.; Madetoja, M.; Koskinen, K.; Oksanen, T. Antitumor effect of oncolytic virus and paclitaxel encapsulated in extracellular vesicles for lung cancer treatment. J. Control. Release 2018, 283, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zou, H.; Tian, X.; Hu, J.; Qiu, P.; Hu, H.; Yan, G. Liposome Encapsulation of Oncolytic Virus M1 To Reduce Immunogenicity and Immune Clearance in Vivo. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenner, A.L.; Frascoli, F.; Yun, C.-O.; Kim, P.S. Optimising Hydrogel Release Profiles for Viro-Immunotherapy Using Oncolytic Adenovirus Expressing IL-12 and GM-CSF with Immature Dendritic Cells. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le, T.M.D.; Jung, B.K.; Li, Y.; Duong, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.L.; Hong, J.W.; Yun, C.O.; Lee, D.S. Physically crosslinked injectable hydrogels for long-term delivery of oncolytic adenoviruses for cancer treatment. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 4195–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chyzy, A.; Tomczykowa, M.; Plonska-Brzezinska, M.E. Hydrogels as potential nano-, micro-and macro-scale systems for controlled drug delivery. Materials 2020, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Qian, Z.; Liu, F.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Gu, Y. In vivo non-invasive optical imaging of temperature-sensitive co-polymeric nanohydrogel. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 185707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Park, K. Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 53, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Chang, D.; Wang, S.; Jiang, T. A novel nanogel delivery of poly-α, β-polyasparthydrazide by reverse microemulsion and its redox-responsive release of 5-Fluorouridine. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, R.; Yang, S.; Guan, J.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, H. Research progress of self-assembled nanogel and hybrid hydrogel systems based on pullulan derivatives. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wan, J.; Xiao, C.; Guan, J.; Song, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Cui, H. A simple glutathione-responsive turn-on theranostic nanoparticle for dual-modal imaging and chemo-photothermal combination therapy. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 5806–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Kim, W.J.; Yoo, H.S. Dual-Responsive Breakdown of Nanostructures with High Doxorubicin Payload for Apoptotic Anticancer Therapy. Small 2013, 9, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, G.; Swanson, J.A.; Lee, K.-D. Drug delivery strategy utilizing conjugation via reversible disulfide linkages: Role and site of cellular reducing activities. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003, 55, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.S.; Dzojic, H.; Nilsson, B.; Totterman, T.H.; Essand, M. An oncolytic conditionally replicating adenovirus for hormone-dependent and hormone-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006, 13, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, E.; Essand, M.; Kraaij, R.; Adamson, R.; Maitland, N.J.; Bangma, C.H. Preclinical safety assessment of Ad[I/PPT-E1A], a novel oncolytic adenovirus for prostate cancer. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2014, 25, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, P.; Tilgase, A.; Rasa, A.; Bandere, K.; Venskus, D. The advent of oncolytic virotherapy in oncology: The Rigvir(R) story. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 837, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donina, S.; Strele, I.; Proboka, G.; Auzins, J.; Alberts, P.; Jonsson, B.; Venskus, D.; Muceniece, A. Adapted ECHO-7 virus Rigvir immunotherapy (oncolytic virotherapy) prolongs survival in melanoma patients after surgical excision of the tumour in a retrospective study. Melanoma Res. 2015, 25, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilgase, A.; Olmane, E.; Nazarovs, J.; Brokane, L.; Erdmanis, R.; Rasa, A.; Alberts, P. Multimodality Treatment of a Colorectal Cancer Stage IV Patient with FOLFOX-4, Bevacizumab, Rigvir Oncolytic Virus, and Surgery. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2018, 12, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, P.; Olmane, E.; Brokane, L.; Krastina, Z.; Romanovska, M.; Kupcs, K.; Isajevs, S.; Proboka, G.; Erdmanis, R.; Nazarovs, J.; et al. Long-term treatment with the oncolytic ECHO-7 virus Rigvir of a melanoma stage IV M1c patient, a small cell lung cancer stage IIIA patient, and a histiocytic sarcoma stage IV patient-three case reports. APMIS 2016, 124, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercruysse, K.P.; Marecak, D.M.; Marecek, J.F.; Prestwich, G.D. Synthesis and in vitro degradation of new polyvalent hydrazide cross-linked hydrogels of hyaluronic acid. Bioconjug Chem. 1997, 8, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agas, D.; Laus, F.; Lacava, G.; Marchegiani, A.; Deng, S.; Magnoni, F.; Silva, G.G.; di Martino, P.; Sabbieti, M.G.; Censi, R. Thermosensitive hybrid hyaluronan/p(HPMAm-lac)-PEG hydrogels enhance cartilage regeneration in a mouse model of osteoarthritis. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 20013–20027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogh, J.; Fogh, J.M.; Orfeo, T. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1977, 59, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthana, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Welford, A.; Hughes, R.; Tazzyman, S.; Essand, M.; Morrow, F.; Lewis, C.E. Macrophage delivery of an oncolytic virus abolishes tumor regrowth and metastasis after chemotherapy or irradiation. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yuan, F.; Dellian, M.; Fukumura, D.; Leunig, M.; Berk, D.A.; Torchilin, V.P.; Jain, R.K. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: Molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 3752–3756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Xu, Z. In vivo antitumor activity of chitosan nanoparticles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4243–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.A.; Parks, R.J. Adenovirus virion stability and the viral genome: Size matters. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 1664–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W. Adenoviruses: Update on structure and function. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, A.; Dzojic, H.; Nilsson, B.; Essand, M. Increased therapeutic efficacy of the prostate-specific oncolytic adenovirus Ad [I/PPT-E1A] by reduction of the insulator size and introduction of the full-length E3 region. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Eldridge, D.; Palombo, E.; Harding, I. Optimisation and stability assessment of solid lipid nanoparticles using particle size and zeta potential. J. Phys. Sci. 2014, 25, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Honary, S.; Zahir, F. Effect of zeta potential on the properties of nano-drug delivery systems-a review (Part 2). Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 12, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Das, S.; De, A.K.; Kar, N.; Bera, T. Amphotericin B-loaded mannose modified poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) polymeric nanoparticles for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis: In vitro and in vivo approaches. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 29575–29590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Urrusuno, R.; Calvo, P.; Remuñán-López, C.; Vila-Jato, J.L.; Alonso, M.J. Enhancement of nasal absorption of insulin using chitosan nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 1999, 16, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumustas, M.; Sengel-Turk, C.T.; Gumustas, A.; Ozkan, S.A.; Uslu, B. Effect of polymer-based nanoparticles on the assay of antimicrobial drug delivery systems. In Multifunctional Systems for Combined Delivery, Biosensing and Diagnostics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 67–108. [Google Scholar]

- Essendoubi, M.; Gobinet, C.; Reynaud, R.; Angiboust, J.; Manfait, M.; Piot, O. Human skin penetration of hyaluronic acid of different molecular weights as probed by Raman spectroscopy. Skin Res. Technol. 2016, 22, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkrad, J.A.; Mrestani, Y.; Stroehl, D.; Wartewig, S.; Neubert, R. Characterization of enzymatically digested hyaluronic acid using NMR, Raman, IR, and UV–Vis spectroscopies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2003, 31, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansil, R.; Yannas, I.; Stanley, H. Raman spectroscopy: A structural probe of glycosaminoglycans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1978, 541, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bazylewski, P.; Divigalpitiya, R.; Fanchini, G. In situ Raman spectroscopy distinguishes between reversible and irreversible thiol modifications in l-cysteine. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 2964–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Wart, H.E.; Lewis, A.; Scheraga, H.A.; Saeva, F.D. Disulfide bond dihedral angles from Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 2619–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wen, Z.Q. Raman spectroscopy of protein pharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 2861–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhong, S.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L.; He, S.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Gao, Y.; Cui, X. Sonochemical preparation of folic acid-decorated reductive-responsive ε-poly-L-lysine-based microcapsules for targeted drug delivery and reductive-triggered release. Mater Sci. Eng. C Mater Biol. Appl. 2020, 106, 110251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.; Honen, R.; Turjeman, K.; Gabizon, A.; Kost, J.; Barenholz, Y. Ultrasound triggered release of cisplatin from liposomes in murine tumors. J. Control. Release 2009, 137, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Shan, M.; Li, B.; Wu, G. A pH and redox dual stimuli-responsive poly(amino acid) derivative for controlled drug release. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 146, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, L. Clearance of hyaluronan from the circulation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1991, 7, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.-B.; Xia, W.-J.; Dong, H.-Q.; Li, Y.-Y. Sheddable micelles based on disulfide-linked hybrid PEG-polypeptide copolymer for intracellular drug delivery. Polymer 2011, 52, 3580–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelsson, S.; Jonsson, N.; Gullberg, M.; Lindberg, A.M. Cytolytic replication of echoviruses in colon cancer cell lines. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Gao, C.; Lü, S.; Liu, M. Redox-responsive core-cross-linked mPEGylated starch micelles as nanocarriers for intracellular anticancer drug release. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 83, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Biswas, A.; Hu, B.; Joo, K.I.; Wang, P.; Gu, Z.; Tang, Y. Redox-responsive nanocapsules for intracellular protein delivery. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 5223–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Name | Particle Size (nm) | PDI | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empty nanohydrogel | 426 ± 12 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | −13.2 ± 1.6 |

| Ad[I/PPT-E1A]-loaded nanohydrogel | 362 ± 19 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | −12.7 ± 0.9 |

| Empty nanohydrogel | 431 ± 13 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | −13.2 ± 3.2 |

| ECHO-7-loaded nanohydrogel | 347 ± 10 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | −13.1 ± 2.9 |

| Raman Shifts (cm−1) | Assignment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurements | References | Bonds | Contributed Polymer | ||

| No. | HA-SH | Nanohydrogel | |||

| 1 | -- | 501 | 498 [76,77,78] | S-S str | disulfide cross-linked core |

| 2 | -- | 565 | 560 [76,77,78] | S-S bend | disulfide cross-linked core |

| 3 | 666 | 662 | 660 [76] | C-S str | linkage of thiol group on HA chain |

| 4 | 889 | 883 | 889 [73,74,75] | -- | HA |

| 5 | 941 | 940 | 949 [73,74,75] | -- | HA |

| 6 | 1037 | 1038 | 1047 [73,74,75] | C-Cstr C-Ostr | HA |

| 7 | 1084 | 1090 | 1091[73,74,75] | C-OHbend acetyl group | HA |

| 8 | 1120 | 1118 | 1125 [73,74,75] | C(4)-OHbend C(4)-Hbend | HA |

| 9 | 1207 | 1206 | 1205 [73,74,75] | CH2twist | HA |

| 10 | 1329 | 1316 | 1328 [73,74,75] | C-Hbend Amide III | HA |

| 11 | 1374 | 1366 | 1372 [73,74,75] | C-Hbend | HA |

| 12 | 1409 | 1405 | 1406 [73,74,75] | C-Nstr C-Hdef | HA |

| 13 | 1645 | 1644 | 1660 [73,74,75] | C=C Amide I | HA |

| 14 | 2557 | -- | 2574 [76] | -SHstr | thiol group |

| 15 | 2905 | 2905 | 2904 [73,74,75] | C-Hstr | HA |

| 16 | 2933 | 2933 | 2933 [73,74,75] | N-Hstr | HA |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, S.; Iscaro, A.; Zambito, G.; Mijiti, Y.; Minicucci, M.; Essand, M.; Lowik, C.; Muthana, M.; Censi, R.; Mezzanotte, L.; et al. Development of a New Hyaluronic Acid Based Redox-Responsive Nanohydrogel for the Encapsulation of Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Immunotherapy. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010144

Deng S, Iscaro A, Zambito G, Mijiti Y, Minicucci M, Essand M, Lowik C, Muthana M, Censi R, Mezzanotte L, et al. Development of a New Hyaluronic Acid Based Redox-Responsive Nanohydrogel for the Encapsulation of Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Immunotherapy. Nanomaterials. 2021; 11(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Siyuan, Alessandra Iscaro, Giorgia Zambito, Yimin Mijiti, Marco Minicucci, Magnus Essand, Clemens Lowik, Munitta Muthana, Roberta Censi, Laura Mezzanotte, and et al. 2021. "Development of a New Hyaluronic Acid Based Redox-Responsive Nanohydrogel for the Encapsulation of Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Immunotherapy" Nanomaterials 11, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010144