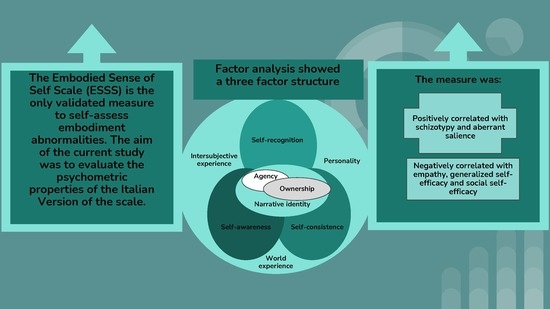

Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Embodied Sense-of-Self Scale

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Sense of ownership: the pre-reflective experience or sense that I am the subject of the movement (e.g., the kinaesthetic experience of movement).

- Sense of agency: the pre-reflective experience or sense that I am the author of the action (e.g., the experience that I am in control of my action) [8]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.1.1. Italian Adaptation of the Scale

2.1.2. Sample Size

2.1.3. Participants

2.2. Current Study

2.2.1. Summary of Hypotheses

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Embodied Sense-of-Self Scale (ESSS)

2.3.2. The Perceptual Aberration Scale (PAS)

2.3.3. The Aberrant Salience Inventory (ASI)

2.3.4. The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)

2.3.5. The Italian Short Empathy Quotient Scale (EQ-Short)

2.3.6. The Perceived Empathic Self-Efficacy (PESE)/Perceived Social Self-Efficacy Scale (PSSE)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Factor Structure

3.3. Reliability and Validity

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peer, M.; Lyon, R.; Arzy, S. Orientation and disorientation: Lessons from patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014, 41, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallup, G.G.; Anderson, J.R. The “olfactory mirror” and other recent attempts to demonstrate self- recognition in non-primate species. Behav. Process. 2018, 148, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botvinick, M.; Cohen, J. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 1998, 391, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limanowski, J. Precision control for a flexible body representation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 134, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 1355–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapur, S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: A framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asai, T.; Kanayama, N.; Imaizumi, S.; Koyama, S.; Kaganoi, S. Development of Embodied Sense of Self Scale (ESSS): Exploring Everyday Experiences Induced by Anomalous Self-Representation. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallagher, S. Philosophical conceptions of the self: Implications for cognitive science. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanghellini, G. Embodiment and schizophrenia. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asai, T.; Mao, Z.; Sugimori, E.; Tanno, Y. Rubber hand illusion, empathy, and schizotypal experiences in terms of self-other representations. Conscious. Cogn. 2011, 20, 1744–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, L.; Bonoldi, I.; Rocchetti, M.; Samson, C.; Azis, M.; Queen, B.; Bossong, M.; Perez, J.; Stone, J.; Allen, P.; et al. An initial investigation of abnormal bodily phenomena in subjects at ultra high risk for psychosis: Their prevalence and clinical implications. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 66, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kállai, J.; Hegedüs, G.; Feldmann, A.; Rózsa, S.; Darnai, G.; Herold, R.; Dorn, K.; Kincses, P.; Csathó, A.; Szolcsányi, T. Temperament and psychopathological syndromes specific susceptibility for rubber hand illusion. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, D.M.; Przybeck, T.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, R. A caveat on using single-item versus multiple-item scales. J. Manag. Psychol. 2002, 17, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnas, J.; Møller, P.; Kircher, T.; Thalbitzer, J.; Jansson, L.; Handest, P.; Zahavi, D. EASE: Examination of Anomalous Self-Experience. Psychopathology 2005, 38, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanghellini, G.; Ballerini, M.; Cutting, J. Abnormal bodily phenomena questionnaire. J. Psychopathol. 2014, 20, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, D.; Stanghellini, G.; Mucci, A.; Ballerini, M.; Giordano, G.M.; Lysaker, P.H.; Galderisi, S. Autism Rating Scale: A New Tool for Characterizing the Schizophrenia Phenotype. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 622359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.J.; Chapman, J.P.; Raulin, M.L. Body-image aberration in schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1978, 87, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, L.; Ratcliffe, M. Atmosphere: On the Phenomenology of “Atmospheric” Alterations in Schizophrenia—Overall Sense of Reality, Familiarity, Vitality, Meaning, or Relevance (Ancillary Article to EAWE Domain 5). Psychopathology 2017, 50, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, D.C.; Kerns, J.G.; McCarthy, D.M. The Aberrant Salience Inventory: A new measure of psychosis proneness. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallese, V. Bodily selves in relation: Embodied simulation as second-person perspective on intersubjectivity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. General Self-Efficacy Scale [Data Set]; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senese, V.P.; De Nicola, A.; Passaro, A.; Ruggiero, G. The factorial structure of a 15-item version of the Italian Empathy Quotient Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 34, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanghellini, G.; Ballerini, M. Dis-sociality: The phenomenological approach to social dysfunction in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giunta, L.; Eisenberg, N.; Kupfer, A.; Steca, P.; Tramontano, C.; Caprara, G.V. Assessing Perceived Empathic and Social Self-Efficacy Across Countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taasoobshirazi, G.; Wang, S. The performance of the SRMR, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI: An examination of sample size, path size, and degrees of freedom. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2016, 11, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos (Version 24.0) [Computer Program]; IBM SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Child, D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sandsten, K.E.; Nordgaard, J.; Kjaer, T.W.; Gallese, V.; Ardizzi, M.; Ferroni, F.; Petersen, J.; Parnas, J. Altered self-recognition in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 218, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallé, L.; Dondé, C.; Gawęda, Ł.; Brunelin, J.; Mondino, M. Impaired self-recognition in individuals with no full-blown psychotic symptoms represented across the continuum of psychosis: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 2864–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allé, M.C.; d’Argembeau, A.; Schneider, P.; Potheegadoo, J.; Coutelle, R.; Danion, J.-M.; Berna, F. Self-continuity across time in schizophrenia: An exploration of phenomenological and narrative continuity in the past and future. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 69, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, T.; Thomsen, D.K.; Bliksted, V. Life story chapters and narrative self-continuity in patients with schizophrenia. Conscious. Cogn. 2016, 45, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sokol, Y.; Serper, M.R. Temporal Self, Psychopathology, and Adaptive Functioning Deficits: An Examination of Acute Psychiatric Patients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, T.; Koch, S.C. Embodied affectivity: On moving and being moved. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, C.G.; Walker, J.B.; Martin, E.A.; Healey, K.M.; Moberg, P.J. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Schizophr. Bull. 2010, 36, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stanghellini, G.; Ricca, V. Alexithymia and schizophrenias. Psychopathology 1995, 28, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Score |

|---|---|

| ESSS | 59.42 ± 15.30 |

| PAS | 5.22 ± 4.79 |

| ASI | 12.49 ± 6.64 |

| GSES | 29.27 ± 4.47 |

| EQ-short | 45.26 ± 5.25 |

| PESE | 23.61 ± 3.03 |

| PSSE | 15.47 ± 2.69 |

| Item | Communality |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.293 |

| 2 | 0.328 |

| 3 | 0.316 |

| 4 | 0.362 |

| 5 | 0.001 |

| 6 | 0.356 |

| 7 | 0.419 |

| 8 | 0.228 |

| 9 | 0.346 |

| 10 | 0.552 |

| 11 | 0.313 |

| 12 | 0.449 |

| 13 | 0.338 |

| 14 | 0.239 |

| 15 | 0.444 |

| 16 | 0.363 |

| 17 | 0.119 |

| 18 | 0.245 |

| 19 | 0.281 |

| 20 | 0.221 |

| 21 | 0.088 |

| 22 | 0.299 |

| 23 | 0.022 |

| 24 | 0.193 |

| 25 | 0.138 |

| Item | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0.646 | 0.190 | 0.034 |

| 2 | 0.755 | 0.072 | 0.121 |

| 3 | 0.642 | 0.302 | −0.041 |

| 4 | 0.579 | 0.318 | 0.079 |

| 6 | 0.669 | 0.120 | 0.235 |

| 7 | 0.506 | 0.473 | 0.094 |

| 8 | 0.570 | 0.051 | 0.195 |

| 9 | 0.627 | 0.194 | 0.175 |

| 10 | 0.355 | 0.645 | 0.260 |

| 11 | 0.046 | 0.728 | 0.155 |

| 12 | 0.278 | 0.639 | 0.209 |

| 13 | 0.205 | 0.456 | 0.353 |

| 14 | 0.045 | 0.720 | 0.012 |

| 15 | 0.342 | 0.603 | 0.153 |

| 16 | 0.240 | 0.619 | 0.162 |

| 18 | 0.095 | 0.215 | 0.685 |

| 19 | 0.194 | 0.046 | 0.838 |

| 20 | 0.037 | 0.146 | 0.822 |

| 22 | 0.224 | 0.255 | 0.532 |

| Item | Mean | SD | Item-Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.68 | 1.114 | 0.470 |

| 2 | 1.44 | 0.936 | 0.503 |

| 3 | 1.53 | 1.004 | 0.505 |

| 4 | 1.54 | 1.018 | 0.532 |

| 6 | 1.52 | 1.045 | 0.534 |

| 7 | 1.93 | 1.285 | 0.590 |

| 8 | 1.91 | 1.206 | 0.413 |

| 9 | 1.89 | 1.237 | 0.530 |

| 10 | 2.15 | 1.278 | 0.693 |

| 11 | 3.00 | 1.358 | 0.497 |

| 12 | 2.36 | 1.375 | 0.611 |

| 13 | 3.39 | 1.269 | 0.518 |

| 14 | 3.02 | 1.324 | 0.427 |

| 15 | 2.85 | 1.255 | 0.605 |

| 16 | 2.45 | 1.459 | 0.548 |

| 18 | 2.34 | 1.350 | 0.447 |

| 19 | 2.03 | 1.244 | 0.470 |

| 20 | 2.17 | 1.339 | 0.425 |

| 22 | 1.70 | 1.043 | 0.483 |

| ESSS-R | ESSS-C | ESSS-A | ESSS total | PAS | GSES | EQ-Short | ASI | PESE | PSSE | |

| ESSS-R | 1 | 0.610 *** | 0.376 *** | 0.848 *** | 0.666 *** | −0.060 | −0.170 ** | 0.551 *** | 0.175 ** | −0.119 |

| ESSS-C | 0.610 *** | 1 | 0.475 *** | 0.889 *** | 0.476 *** | −0.206 ** | −0.143 * | 0.469 *** | 0.008 | −0.153 * |

| ESSS-A | 0.376 *** | 0.475 *** | 1 | 0.686 *** | 0.294 *** | −0.141 * | −0.060 | 0.328 *** | 0.006 | −0.028 |

| ESSS total | 0.848 *** | 0.889 *** | 0.686 *** | 1 | 0.609 ** | −0.165 ** | −0.160 ** | 0.561 *** | 0.093 | −0.133 * |

| PAS | 0.666 *** | 0.476 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.609 ** | 1 | −0.041 | −0.196 ** | 0.562 *** | 0.153 * | −0.107 |

| GSES | −0.060 | −0.206 ** | −0.141 * | −0.165 *** | −0.041 | 1 | 0.128 * | 0.022 | 0.138 * | 0.201 ** |

| EQ-short | −0.170 ** | −0.143 * | −0.060 | −0.160** | −0.196 ** | 0.128 * | 1 | −0.055 | 0.499 *** | 0.484 *** |

| ASI | 0.551 *** | 0.469 *** | 0.328 *** | 0.561 *** | 0.562 *** | 0.022 | −0.055 | 1 | 0.130 * | −0.022 |

| PESE | 0.175 ** | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.093 | 0.153 * | 0.138 * | 0.499 *** | 0.130 * | 1 | 0.300 *** |

| PSSE | −0.119 | −0.153 * | −0.028 | −0.133 * | −0.107 | 0.201 ** | 0.484 *** | −0.022 ** | 0.300 *** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patti, A.; Santarelli, G.; Baccaredda Boy, O.; Fascina, I.; Altomare, A.I.; Ballerini, A.; Ricca, V. Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Embodied Sense-of-Self Scale. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13010034

Patti A, Santarelli G, Baccaredda Boy O, Fascina I, Altomare AI, Ballerini A, Ricca V. Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Embodied Sense-of-Self Scale. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13010034

Chicago/Turabian StylePatti, Andrea, Gabriele Santarelli, Ottone Baccaredda Boy, Isotta Fascina, Arianna Ida Altomare, Andrea Ballerini, and Valdo Ricca. 2023. "Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Embodied Sense-of-Self Scale" Brain Sciences 13, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13010034