1. Introduction

The long-term effects of the space environment on the central nervous system (CNS) still remain largely unknown. Human space travelers experience a unique environment that affects homeostasis and physiological adaptation. In particular, neuro-psycho-physiological health deserves special attention to ensure successful long-term space missions. In recent years, studies have started to address neural function and behavior in space. It has been reported that cerebellar, sensorimotor, and vestibular brain areas seem to be the most affected [

1]. Microgravity reduces central venous and intracranial pressure; nonetheless, intracranial pressure is not reduced to the levels observed in the 90° degrees seated upright posture on Earth. Instead, the basal levels over 24 h in microgravity pressure in the brain are slightly higher than those on Earth, which may cause the remodeling of the eye in astronauts [

2]. Moreover, a space flight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) has been recently described [

3]. At the cellular level, it has been shown that microgravity induces apoptosis, alters the cytoskeleton, and affects the differentiation, proliferation, and metabolic status in different cells [

4]. Nonetheless, only a few aspects regarding the sensitivity of human neural stem cells (hNSCs) in microgravity have been reported. An interesting article from Silvano and collaborators [

5] showed that murine cerebellar neural stem cells (NSCs) respond to simulated microgravity by the arrest of their cell cycle in S-phase and enhanced apoptosis. They also found that these changes were transient and upon return to normal gravity (1 G) these cells recovered their stemness and a normal cell cycle.

The objective of the present study was to determine how the space environment influences human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived NSCs, their biology, and their fate choice capability toward the neuronal phenotype.

2. Methodological Approach

NSCs were derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. The original cells, known as “CS83iCTR-33nxx” (such as skin cells or lymphoblasts), were “reprogrammed” and provided to us by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center via a material transfer agreement.

NSCs were seeded onto an 8-well Petri dish from Airbus-Kiwi (Friedrichshafen, DE), flown to the International Space Station (ISS), and installed in the Space Technology and Advanced Research System Experiment Facility-1 at 37 °C. The cells remained onboard the ISS for 39.3 days and then returned to Earth.

After splashdown, transport to Long Beach airport, and delivery to UCLA, the NSCs were retrieved from the hardware, plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated flasks in our proprietary stem cell chemically defined medium (STM) [

6,

7], and allowed to recover from space flight. Subsequently, some of these NSCs were plated in neuronal specification medium (NSM).

3. Results

3.1. NSCs in Space Environment (SPC) Preserve Their “Stemness” and Proliferate

This experiment was designed to ascertain the proliferation of NSCs solely while in microgravity. In order to elucidate if NSCs in “space microgravity” proliferate, we used the Type IV automated experiment insert from Kiwi (Airbus, Friedrichshafen, DE), allowing for a fresh medium change twice during space travel. The medium within which the cells traveled was replaced with fresh medium containing bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) two days after the cargo berth to the ISS. Therefore, BrdU incorporation took place during three days. NSC cultures were then arrested with the second stem cell medium and placed at 4 °C for further examination upon return to the laboratory (

Scheme 1).

NSCs were seeded onto a mesh-cell carrier because cells adhere firmly to it and have a better resistance to vibrations and g-forces during take-off and re-entry to the atmosphere. This protocol was tested and verified during the science definition phase of the investigation following NASA’s requirements (

Figure 1A).

Upon return, the NSCs were recovered and post-fixed to perform triple immunofluorescence against two NSC markers as previously described [

6]—polysialic acid (PSA) cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), known as PSA-NCAM, and the intermediate filament protein nestin, also known as a neural stem/progenitor cell marker—as well as BrdU for the detection of new DNA as a marker for cell proliferation (

Figure 2).

3.2. Passive Experiments

In order to ascertain the health status of the NSCs, we performed experiments using 8-well Petri dishes from Kiwi (Airbus). We have called these passive experiments, because the cells remained within the same culture medium for 45 days (counting from handover to handover), having spent a total of 39.3 days in space from launch to splashdown of the dragon vehicle and the rest of the time in transit. Upon return, the cells were harvested from the hardware and seeded on poly-d-lysine. After the recovery period, the NSCs were seeded in Seahorse Bioscience XFplates (Agilent) to assess their cellular bioenergetic status. The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR, a measure of glycolysis) were both higher in the NSCs exposed to the space environment as compared to the ground control cells, indicating a higher metabolic state (

Figure 3). These measurements were performed one week after the NSCs returned to Earth. Therefore, one can infer that NSCs “remember” having been in microgravity. Alternatively, re-adaptation to 1 G may have prompted higher energetic needs.

3.3. Fate Choice

After the recovery period, the NSCs were fed with neuronal specification medium (NSM) [

6] in order to obtain neurons. Exposure to a space environment did not alter the NSCs potential to choose the neuronal fate. Interestingly, neuroblasts proliferated for more than 1 week after being in NSM before moving toward maturation. The timeline for neuronal specification is shown in

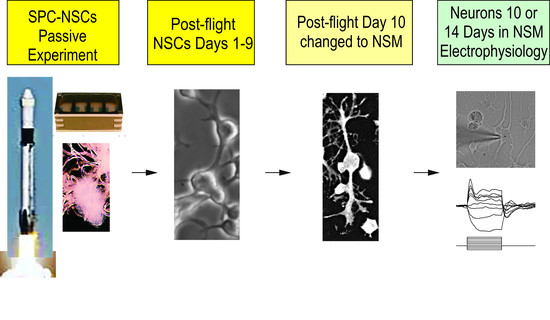

Scheme 2.

Neuronal Specification. Upon their return to Earth, the cells were allowed to recover in NSC medium and standard conditions for 9 days. NSCs were introduced to neuronal specification medium (NSM) on Day 10. After 10 or 14 days of having been in NSM, we examined the electrophysiological properties of these cells.

Electrophysiological recordings of SPC-NSC-derived neurons were obtained 10 days or 14 days after being in NSM using standard procedures, as detailed in our previous publication [

8]

Figure 4.

A total of seven plates containing SPC-NSCs were used, and 16 cells were recorded in voltage and current clamp modes using a K-gluconate-based internal solution. First, passive membrane properties were determined in the voltage clamp mode. The cell membrane capacitance was relatively small (27.3 ± 1.9 pF, mean ± SEM), while the input resistance was high (553.4 ± 84.7 MΩ). The decay time constant was very fast (0.4 ± 0.05 ms). These properties are similar to those obtained from implanted NSCs [

8]. After measuring passive membrane properties, the recording was switched to the current clamp mode. The mean resting membrane potential was relatively depolarized (−38.1 ± 1.8 mV), and upon injection of depolarizing current steps, most cells displayed a small-amplitude action potential, suggesting that these SPC-NSCs were in an immature state. In the gap free mode, we determined that spontaneous synaptic activity was not yet apparent.

4. Discussion

Here we have demonstrated that human NSCs proliferate while in space and that they remain as NSCs after 39.3 days unattended, in the same culture medium, and in space microgravity. Moreover, these cells also keep their ability to become young neurons in the appropriate conditions. Silvano’s team reported data supporting that simulated microgravity arrests cell proliferation, albeit in a transient manner, and they also found that these changes were not permanent as NSCs recovered their proliferative capacity when they were returned to normal gravity.

The apparent contradiction between Silvano’s group reporting the arrest of proliferation data and this study may reside in the fact that the cells they used were from a different species (i.e., mouse vs. human). Additionally, their cells were kept in simulated microgravity for 3 to 5 days, as opposed to our NSCs, which were exposed to SPC microgravity for 5 days at 37 °C and in BrdU for 3 days. Therefore, the reasons for the apparent contradiction may be due to the following: (1) the extent of the exposure to microgravity, which might be a determinant for the arrest of cell proliferation in Silvano’s study or (2) perhaps simulated microgravity differs from space microgravity with respect to the regulation of neural cells and their biological processes. Why a higher bioenergetic state is elicited by microgravity is not clear at the present time. The fact that we demonstrated that NSCs proliferate in space needs to be studied in more detail, as it might be that this phenomenon contributes to the visual impairment and intracranial pressure syndrome (VIIP) exhibited by astronauts in space and upon their return to Earth [

9]. Elucidating the origin of the increased energy needs by brain cells is crucial in order to design effective countermeasures for astronauts working onboard the International Space Station and for long-term space travel. Moreover, here we found that NSCs displayed an elevated energy metabolism; both oxygen consumption and glycolysis were higher than in the ground control counterparts, confirming our previous findings from work using “simulated microgravity” [

10]. We have previously reported that simulated microgravity enhances mitochondrial function in oligodendrocytes (OLs), the myelin forming cells in the CNS [

11]. Two of the main sources of energy for respiration and energy production, glucose and pyruvate, were decreased after just 3 days in microgravity, while lactate levels increased considerably indicating that OLs switched to anaerobic glycolysis in order to meet the energy demands elicited by microgravity [

11].

It is possible that NSCs in space require more energy for proliferation as well as for maintaining homeostasis in an environment where, besides microgravity, there are other factors involved, such as radiation, moving while being packed and unpacked, and variation of g-forces occurring during launching and splashdown. Nonetheless, the cells appeared to be able to recover from such a journey and display their stemness when returned to Earth. Furthermore, as mentioned above, their membrane properties were similar to the NSCs grown in normal gravity.

5. Conclusions

Neurobiology and the environment determine psychological and physiological fitness and behavior; hence, the maintenance of energy metabolism homeostasis is of paramount importance. The formulation of energy rich diets for astronauts, as well as providing an enriched environment, may contribute to reaching and maintaining the balance we all strive for—mens sana in corpore sano (a healthy mind in a healthy body).

The results presented in this communication are also promising for humankind on Earth; neurodegenerative diseases frequently result from the loss of a specific cell population, and it was demonstrated that microgravity is an excellent strategy to increase neural cell numbers without the need of performing genetic manipulations or long-term treatments with mitogens. It is believed that incorporating microgravity into projects of a translational nature will lead the scientific community one step closer toward translational research to address neurodegeneration and the recovery of CNS function.

Author Contributions

C.C. performed the electrophysiology on neuronal cultures, prepared the figure and caption and contributed to manuscript preparation; L.V. performed the energetics assays and statistics; N.C. examined NSCs time-lapse images; M.J.S. and L.A.B. provided support with time-lapse microscopy and processing of the data; F.K. contributed to the development, testing and implementation of the study. A.E.-J. designed the study, performed the work at Kennedy Space Center, recovered the cells from the space hardware upon their return to earth and performed image acquisition of live cells and thereafter performed immunocytochemistry, analysis of the data and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the editing and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

NASA Space Biology Grant: NNX15AB43G; the Cell, Circuits and Systems Analysis Core is supported by the NIH (Grant U54HD087101). Time-lapse microscopy was performed at the Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Laboratory and the Leica Microsystems Center of Excellence at the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA with funding support from NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10OD025017 and NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant CHE-0722519.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mark Mobilia and the entire Zeiss team, Amy Rowat for support with the microscope system. Amy Gresser. Elizabeth Pane, and Medaya Torres for their help with the implementation of the study. The NASA Space Biology Project team at Ames Research Center D. Tomko, K. Sato, E. Taylor, ARC Space Biology Project Manager and the support personnel at the Space Station Processing Facility at Kennedy Space Center. Special thanks to the Kiwi/Airbus and STaARS team members, Uli Kuebler and A. Espinosa de los Monteros for help with the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Van Ombergen, A.; Demertzi, A.; Tomilovskaya, E.; Jeurissen, B.; Sijbers, J.; Kozlovskaya, I.B.; Parizel, P.M.; Van de Heyning, P.H.; Sunaert, S.; Laureys, S.; et al. The effect of spaceflight and microgravity on the human brain. J. Neurol. 2017, 264 (Suppl. 1), 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lawley, J.S.; Petersen, L.G.; Howden, E.J.; Sarma, S.; Cornwell, W.K.; Zhang, R.; Whitworth, L.A.; Williams, M.A.; Levine, B.D. Effect of gravity and microgravity on intracranial pressure. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, A.G.; Mader, T.H.; Gibson, C.R.; Tarver, W. Space Flight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 992–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studer, M.; Bradacs, G.; Hilliger, A.; Hürlimann, E.; Engeli, S.; Thiel, C.S.; Zeitner, P.; Denier, B.; Binggeli, M.; Syburra, T.; et al. Parabolic maneuvers of the Swiss Air Force fighter jet F-5E as a research platform for cell culture experiments in microgravity. Acta Astronaut. 2011, 68, 1729–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvano, M.; Miele, E.; Valerio, M.C.; Casadei, L.; Begalli, F.; Campese, A.F.; Besharat, Z.M.; Alfano, V.; Abballe, L.; Catanzaro, G.; et al. Consequences of Simulated Microgravity in Neural Stem Cells: Biological Effects and Metabolic Response. J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 5, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Jeffrey, A.; Becker-Catania, S.; Zhao, P.M.; Cole, R.; de Vellis, J. Phenotype Specification and Development of Oligodendrocytes and Neurons from Rat Stem Cell Cultures Using Two Chemically Defined Media. Special Issue on Stem cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 69, 810–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Jeffrey, A.; Blanchi, B.; Biancotti, J.C.; Kumar, S.; Hirose, M.; Mandefro, B.; Talavera, D.; Benvenisty, N.; de Vellis, J. Efficient generation of viral and integration free human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived oligodendrocytes. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2016, 38, 2D.18.1–2D.18.27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidling, J.C.; Relaño-Ginés, A.; Holley, S.M.; Ochaba, J.; Moore, C.; Fury, B.; Lau, A.; Tran, A.H.; Yeung, S.; Salamati, D.; et al. Human Neural Stem Cell Transplantation Rescues Functional Deficits in R6/2 and Q140 Huntington’s Disease Mice. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.F.; Hargens, A.R. Spaceflight-Induced Intracranial Hypertension and Visual Impairment: Pathophysiology and Countermeasures. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Espinosa-Jeffrey, A.; Kumar, S.; Wanner, I.; Taniguchi, A.; Oregel, K.; Hirose, M.; Green, J.; Gau, J.; de Vellis, J. Neural Stem Cells Grow and Sustain Their Ability to Self-Renew as Well, as to Commit to a Specific Cell Lineage in Simulated Microgravity: Implication for Cell Replacement Therapies; International Astronautical Federation (IAF): Guadalajara, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Jeffrey, A.; Nguyen, K.; Kumar, S.; Toshimasa, O.; Hirose, R.; Reue, K.; Vergnes, L.; Kinchen, J.; de Vellis, J. Simulated microgravity enhances oligodendrocyte mitochondrial function and lipid metabolism. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 1434–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).