Aelurostrongylus abstrusus Infections in Domestic Cats (Felis silvestris catus) from Antioquia, Colombia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

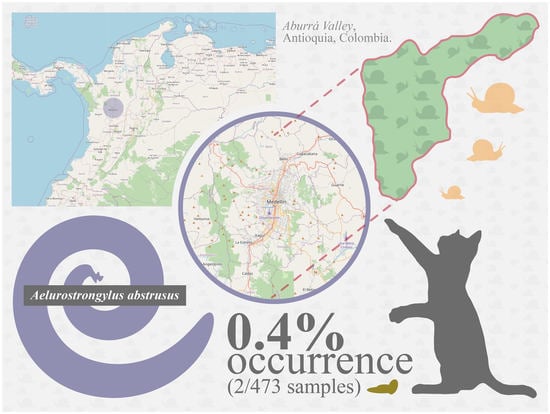

Occurrence of Patent A. abstrusus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conboy, G. Helminth Parasites of the Canine and Feline Respiratory Tract. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pr. 2009, 39, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos-Tabares, F.; Lange, M.K.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C. Angiostrongylus vasorum and Aelurostrongylus abstrusus: Neglected and underestimated parasites in South America. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Penagos-Tabares, F.; Lange, M.K.; Vélez, J.; Hirzmann, J.; Gutiérrez-Arboleda, J.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C.; Gutiérrez, J.J.C. The invasive giant African snail Lissachatina fulica as natural intermediate host of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, Angiostrongylus vasorum, Troglostrongylus brevior, and Crenosoma vulpis in Colombia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerichter, C.B. Studies on the nematodes parasitic in the lungs of Felidae in Palestine. Parasitology 1949, 39, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C. The superfamily Metastrongyloidea. In Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. Their Development and Transmission; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, M.K.; Penagos-Tabares, F.; Muñoz-Caro, T.; Gärtner, U.; Mejer, H.; Schaper, R.; Hermosilla, C.; Taubert, A. Gastropod-derived haemocyte extracellular traps entrap metastrongyloid larval stages of Angiostrongylus vasorum, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus brevior. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giannelli, A.; Ramos, R.A.N.; Annoscia, G.; Di Cesare, A.; Colella, V.; Brianti, E.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Mutafchiev, Y.; Otranto, D. Development of the feline lungworms Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus brevior in Helix aspersa snails. Parasitology 2013, 141, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimzas, D.; Morelli, S.; Traversa, D.; Di Cesare, A.; Van Bourgonie, Y.R.; Breugelmans, K.; Backeljau, T.; Di Regalbono, A.F.; Diakou, A. Intermediate gastropod hosts of major feline cardiopulmonary nematodes in an area of wildcat and domestic cat sympatry in Greece. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuehrer, H.-P.; Morelli, S.; Bleicher, J.; Brauchart, T.; Edler, M.; Eisschiel, N.; Hering, T.; Lercher, S.; Mohab, K.; Reinelt, S.; et al. Detection of Crenosoma spp., Angiostrongylus vasorum and Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in Gastropods in Eastern Austria. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzosi, T.; Perrucci, S.; Parisi, F.; Morelli, S.; Maestrini, M.; Mennuni, G.; Traversa, D.; Poli, A. Fatal Pulmonary Hypertension and Right-Sided Congestive Heart Failure in a Kitten Infected with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. Animals 2020, 10, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traversa, D.; Lia, R.P.; Iorio, R.; Boari, A.; Paradies, P.; Capelli, G.; Avolio, S.; Otranto, D. Diagnosis and risk factors of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (Nematoda, Strongylida) infection in cats from Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2008, 153, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, S.; Diakou, A.; Di Cesare, A.; Schnyder, M.; Colombo, M.; Strube, C.; Dimzas, D.; Latino, R.; Traversa, D. Feline lungworms in Greece: Copromicroscopic, molecular and serological study. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 2877–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traversa, D.; Morelli, S.; Cassini, R.; Crisi, P.E.; Russi, I.; Grillotti, E.; Manzocchi, S.; Simonato, G.; Beraldo, P.; Viglietti, A.; et al. Occurrence of canine and feline extra-intestinal nematodes in key endemic regions of Italy. Acta Trop. 2019, 193, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, A.; Capelli, G.; Joachim, A.; Hinney, B.; Losson, B.; Kirkova, Z.; René-Martellet, M.; Papadopoulos, E.; Farkas, R.; Napoli, E.; et al. Lungworms and gastrointestinal parasites of domestic cats: A European perspective. Int. J. Parasitol. 2017, 47, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagamori, Y.; Payton, M.E.; Looper, E.; Apple, H.; Johnson, E.M. Retrospective survey of parasitism identified in feces of client-owned cats in North America from 2007 through 2018. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 277, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruth, A.J.; Buch, J.S.; Braff, J.C.; Chandrashekar, R.; Bowman, D.D. Distribution of the feline lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in the USA based on fecal testing. J. Feline Med. Surg. Open Rep. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulcan, J.M.; Timmins, A.; Dennis, M.M.; Thrall, M.A.; Lejeune, M.; Abdu, A.; Ketzis, J.K. First report of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in St. Kitts. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2020, 19, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, D.; Vicente, J.J.; Pinto, R.M. A survey of new host records for nematodes from mammals deposited in the Hel-minthological Collection of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (CHIOC). Rev. Bras. Zool. 2002, 19, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusma, S.C.; Wrublewski, D.M.; Teixeira, V.N.; Holdefer, D.R. Parasitos intestinais de Leopardus wiedii e Leopardus tigrinus (Felidae) da Floresta Nacional De Três Barras, SC. Luminária 2015, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Traversa, D.; Morelli, S.; Di Cesare, A.; Diakou, A. Felid Cardiopulmonary Nematodes: Dilemmas Solved and New Questions Posed. Pathogens 2021, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, I.; Cabrera, E.; Cuellar, J.; Murcia, C.; Sánchez, L.; Sánchez, E. Postmortem diagnosis of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (Railliet, 1898) in a mongrel feline: First report in the municipality of Florencia, Department of the Caquetá, Colombia. REDVET Rev. Electrón. Vet. 2017, 18, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca, J.A.; Gil, B.; Cortés, J.A. Parasitosis pulmonar por Aelurostrongylus abstrusus en un felino. Rev. Med. Vet. Zoot. 2003, 50, 30–34, eISSN 2357-3813; ISSN 0120-2952. [Google Scholar]

- Taubert, A.; Pantchev, N.; Vrhovec, M.G.; Bauer, C.; Hermosilla, C. Lungworm infections (Angiostrongylus vasorum, Crenosoma vulpis, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus) in dogs and cats in Germany and Denmark in 2003–2007. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 159, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traversa, D.; Di Cesare, A. Diagnosis and management of lungworm infections in cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Traversa, D.; Guglielmini, C. Feline aelurostrongylosis and canine angiostrongylosis: A challenging diagnosis for two emerging verminous pneumonia infections. Vet. Parasitol. 2008, 157, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.M.; Lima, W.S. Larval production of cats infected and re-infected with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (Nematoda: Protostrongylidae). Rev. Med. Vet. 2001, 152, 815–829. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.W. Current knowledge of Aelurostrongylosis in the cat. Literature review and case reports. Cornell Vet. 1973, 63, 483–500. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheikha, H.M.; Schnyder, M.; Traversa, D.; Di Cesare, A.; Wright, I.; Lacher, D.W. Updates on feline Aelurostrongylosis and research priorities for the next decade. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trein, E.J. Lesões Produzidas por Aelurostrongylus Abstrusus (Railliet, 1898) no Pulmão do Gato Doméstico; Oficinas gráficas da livraria Selbach, Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Fenerich, F.L.; Santos, S.; Ribeiro, L.O. Incidência de Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (Railliet, 1898) (Nematoda: Protostron-gylidae) em gatos de rua da cidade de São Paulo, Brasil. Biológico 1975, 41, 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mundim, T.; Oliveira Júnior, S.; Rodrigues, D.; Cury, M. Frequency of helminthes parasites in cats of Uberlândia, Minas Gerais. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zoo. 2004, 56, 562–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Headley, S.A. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus induced pneumonia in cats: Pathological and epidemiological findings of 38 cases (1987–1996). Semin. Cienc. Agrar. 2005, 26, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramos, D.G.D.S.; Scheremeta, R.G.A.D.C.; De Oliveira, A.C.S.; Sinkoc, A.L.; Pacheco, R.D.C. Survey of helminth parasites of cats from the metropolitan area of Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2013, 22, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehlers, A.; De Mattos, M.J.T.; Marques, S.M.T. Prevalência de Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (Nematoda, Strongylida) em gatos de Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul. Rev. FZVA 2013, 19, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Idiart, J.; Martín, A.; Venturini, L.; Ruager, J. Neumonía por Aelurostrongylus abstrusus en gatos. Primeros hallazgos en el gran Buenos Aires y La Plata. Vet. Argent. 1986, 23, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, A.; Santa Cruz, A.; Lombardero, O. Histopathological lesions in feline aelurostrongylosis. Rev. Med. Vet. 1990, 71, 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerfelt, I.; Cardillo, N.; López, C.; Ribicich, M.; Gallo, C.; Franco, A. Prevalence of Toxocara cati and other parasites in cats’ faeces collected from the open spaces of public institutions: Buenos Aires, Argentina. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 140, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, L.; Levratto, R.; Sobrero, T. Estudio estadístico de la incidencia parasitaria en animales domésticos. An. Fac. Vet. Urug. 1961, 10, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, O.; Valledor, S.; Crampet, A.; Casás, G. Aporte al conocimiento de los metazoos parásitos del gato doméstico en el Departamento de Montevideo, Uruguay. Veterinaria 2013, 49, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzún-Cadagán, J.A. Pesquisa de Nematodos Pulmonares en Perros y Gatos de las Ciudades de Río Bueno y La Unión, Provincia del Ranco, Chile; Universidad Austral De Chile Valdivia: Valdivia, Chile, 2013; Available online: http://cybertesis.uach.cl/tesis/uach/2013/fvo.98p/doc/fvo.98p.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Echeverry, D.M.; Giraldo, M.I.; Castaño, J.C. Prevalence of intestinal helminths in cats in Quindío, Colombia. Biomédica 2012, 32, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grandi, G.; Calvi, L.; Venco, L.; Paratici, C.; Genchi, C.; Memmi, D.; Kramer, L. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (cat lungworm) infection in five cats from Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 134, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traversa, D.; Milillo, P.; Di Cesare, A.; Lohr, B.; Iorio, R.; Pampurini, F.; Schaper, R.; Bartolini, R.; Heine, J. Efficacy and Safety of Emodepside 2.1 %/Praziquantel 8.6% Spot-on Formulation in the Treatment of Feline Aelurostrongylosis. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisi, P.E.; Di Cesare, A.; Traversa, D.; Vignoli, M.; Morelli, S.; Di Tommaso, M.; De Santis, F.; Pampurini, F.; Schaper, R.; Boari, A. Controlled field study evaluating the clinical efficacy of a topical formulation containing emodepside and praziquantel in the treatment of natural cat Aelurostrongylosis. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knaus, M.; Chester, S.T.; Rosentel, J.; Kühnert, A.; Rehbein, S. Efficacy of a novel topical combination of fipronil, (S)-methoprene, eprinomectin and praziquantel against larval and adult stages of the cat lungworm, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 202, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dirven, M.; Szatmári, V.; Ingh, T.V.D.; Nijsse, R. Reversible pulmonary hypertension associated with lungworm infection in a young cat. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2012, 14, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannino, F.; Iannetti, L.; Paganico, D.; Vulpiani, M.P. Evaluation of the efficacy of selamectin spot-on in cats infested with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (Strongylida, Filariodidae) in a Central Italy cat shelter. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 197, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brianti, E.; Giannetto, S.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Otranto, D. Lungworms of the genus Troglostrongylus (Strongylida: Crenosomatidae): Neglected parasites for domestic cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 202, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brianti, E.; Gaglio, G.; Giannetto, S.; Annoscia, G.; Latrofa, M.S.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Traversa, D.; Otranto, D. Troglostrongylus brevior and Troglostrongylus subcrenatus (Strongylida: Crenosomatidae) as agents of broncho-pulmonary infestation in domestic cats. Parasites Vectors 2012, 5, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LaCorcia, L.; Gasser, R.B.; Anderson, G.A.; Beveridge, I. Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid examination and other diagnostic techniques with the Baermann technique for detection of naturally occurring Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infection in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2009, 235, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare, A.; Gueldner, E.K.; Traversa, D.; Veronesi, F.; Morelli, S.; Crisi, P.E.; Pampurini, F.; Strube, C.; Schnyder, M. Seroprevalence of antibodies against the cat lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in cats from endemic areas of Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 272, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zottler, E.-M.; Strube, C.; Schnyder, M. Detection of specific antibodies in cats infected with the lung nematode Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 235, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gueldner, E.K.; Gilli, U.; Strube, C.; Schnyder, M. Seroprevalence, biogeographic distribution and risk factors for Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infections in Swiss cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 266, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalera, M.A.; Schnyder, M.; Gueldner, E.K.; Furlanello, T.; Iatta, R.; Brianti, E.; Strube, C.; Colella, V.; Otranto, D. Serological survey and risk factors of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infection among owned cats in Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 2377–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloss, M.W.; Kemp, R.L.; Zajac, A.M. Fecal examination: Dogs and cats. In Veterinary Clinical Parasitology, 6th ed.; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez-Osorio, S.; Navarro-Ruiz, J.L.; Rave, A.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C.; Chaparro-Gutierrez, J.J. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus Infections in Domestic Cats (Felis silvestris catus) from Antioquia, Colombia. Pathogens 2021, 10, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10030337

Lopez-Osorio S, Navarro-Ruiz JL, Rave A, Taubert A, Hermosilla C, Chaparro-Gutierrez JJ. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus Infections in Domestic Cats (Felis silvestris catus) from Antioquia, Colombia. Pathogens. 2021; 10(3):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10030337

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez-Osorio, Sara, Jeffer Leonardo Navarro-Ruiz, Astrid Rave, Anja Taubert, Carlos Hermosilla, and Jenny J. Chaparro-Gutierrez. 2021. "Aelurostrongylus abstrusus Infections in Domestic Cats (Felis silvestris catus) from Antioquia, Colombia" Pathogens 10, no. 3: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10030337