Influence of a Protective Coating on the Crystallization of an Amorphous Fe78Si13B9 Alloy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

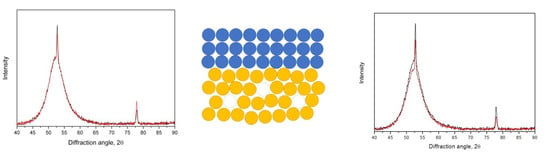

3.1. Crystallization of the as-Quenched Samples

3.2. Crystallization of the Samples with a Ta Coating

3.3. Crystallization of the Samples after Preliminary Ultrasonic Treatment

3.4. Crystallization of the Samples with Ta Coating after Ultrasonic Treatment

- −

- the fraction of the crystalline phase in the annealed samples with a protective coating is larger than that in the samples annealed without a protective coating;

- −

- the fraction of the crystalline phase increases if the samples were preliminarily subjected to ultrasonic treatment.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, Y.H.; Inoue, A.; Masumoto, T. Increase in Mechanical Strength of Al–Y–Ni Amorphous Alloys by Dispersion of Nanoscale fcc-Al Particles. Mater. Trans. JIM 1991, 32, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoue, A.; Ochiai, T.; Horio, Y.; Masumoto, T. Formation and mechanical properties of amorphous Al-Ni-Nd alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1994, A179–A180, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F.; Greer, A. Metallic glasses as structural materials. Scr. Mater. 2004, 54, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, M.M.; Thadhani, N.N. Mechanical properties of bulk metallic glasses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2010, 55, 759–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ri, M.C.; Ding, D.W.; Sun, B.A.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhu, X.S.; Wang, B.B.; Wang, T.L.; Qiu, Q.Q.; Huo, L.S.; Wang, W.H. Stress effects on magnetic property of Fe-based metallic glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 495, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Aronin, A. Nanocrystal formation in Al- and Ti-based amorphous alloys at Deformation. J. Alloys Comp. 2018, 747, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, A.; Zhukova, V.; Ipatov, M.; del Val, J.J.; Gonzalez-Legarreta, L.; Hernando, B.; Blanco, M.; Zhukov, A. Effect of nanocrystallization on giant magnetoimpedance effect of Fe-based microwires. Intermetallics 2014, 51, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, G. Anisotropies in soft magnetic nanocrystalline alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 294, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, S.; Rezaei-Shahreza, P.; Seifoddini, A.; Hakimi, M. Enhanced glass forming ability, mechanical, and magnetic properties of Fe41Co7Cr15Mo14Y2C15B6 bulk metallic glass with minor addition of Cu. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 497, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukova, V.; Ipatov, M.; CorteLeon, P.; Blanco, J.M.; Zanaeva, E.; Bazlov, A.I.; Jiang, J.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V.; Olivera, J.; Zhukov, A. Excellent magnetic properties of (Fe0.7Co0.3)83.7Si4B8P3.6Cu0.7 ribbons and microwires. Intermetallics 2020, 117, 106660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, A.; Abrosimova, G.; Aksenov, O.; Churyukanova, M.; Aronin, A. The Influence of Internal Stress on the Nanocrystal Formation of Amorphous Fe73.8Si13B9.1Cu1Nb3.1 Microwires and Ribbons. Crystals 2022, 12, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, R.; Wang, A.; Dong, Y.; He, A.; Ni, H.; Liu, C.-T. Magnetic and thermal stabilities of FeSiB eutectic amorphous alloys: Compositional effects. J. Alloys Comp. 2019, 776, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazlov, A.I.; Tabachkova, N.Y.; Zolotorevsky, V.S.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. Unusual crystallization of Al85Y8Ni5Co2 metallic glass observed in situ in TEM at different heating rates. Intermetallics 2018, 94, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Hashimoto, K. Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Materials. In Advances in Materials Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.; Hashemi, S.H.; Ashrafi, A.; Razavi, R.S.; Mirsaeed, S.M.G. Characterization and corrosion behavior of Al–Co–rare earth (Ce–La) amorphous alloy. J. Rare Earths, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, K.; Che, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, B. Preparation of Al-based amorphous coatings and their properties. J. Rare Earths 2021, 39, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Tournier, R.F. On structural rearrangements near the glass transition temperature in amorphous silica. Materials 2021, 14, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. On Structural Rearrangements during the Vitrification of Molten Copper. Materials 2022, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. Structural Changes in Metallic Glass-Forming Liquids on Cooling and Subsequent Vitrification in Relationship with Their Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronin, A.S.; Abrosimova, G.E.; Gurov, A.F.; Kir’yanov, Y.V.; Molokanov, V.V. Nanocrystallization of bulk Zr–Cu–Ti metallic glass. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2001, A304–A306, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucharat, N.; Hebert, R.; Rösner, H.; Valiev, R.; Wilde, G. Synthesis routes for controlling the microstructure in nanostructured Al88Y7Fe5 alloys. J. Alloys Comp. 2007, 434–435, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Aronin, A. On decomposition of amorphous phase in metallic glasses. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2017, 50, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, A.L.; Cheng, Y.Q.; Ma, E. Shear bands in metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2013, 74, 71–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, M.; Das, J.; Bednarcik, J.; Franz, H.; Mattern, N.; Wang, W.H.; Eckert, J. Strain distribution in Zr64.13Cu15.75Ni10.12Al10 bulk metallic glass investigated by in situ tensile tests under synchrotron radiation. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 013522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronin, A.; Abrosimova, G.; Matveev, D.; Rybchenko, O. Structure and properties of nanocrystalline alloys prepared by high pressure torsion. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2010, 25, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rösner, H.; Peterlechler, M.; Kűbel, C.; Schmidt, V.; Wilde, G. Density changes in shear bands of a metallic glass determined by correlative analytical transmission electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 2014, 142, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Feng, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. Severe deformation-induced microstructural heterogeneities in Cu64Zr36 metallic glass. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 30, 065005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Aronin, A.; Matveev, D.; Pershina, E. Nanocrystal formation, structure and magnetic properties of Fe-Si-B amorphous alloy after deformation. Mater. Lett. 2013, 97, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.H.; Pang, J.; Wang, X.; Wen, K.; Guo, L.Y.; Kim, K.B.; Wang, W.M. Anisotropic magnetization improvement in Fe78Si9B13 glass with direct current heating. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 448, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pang, J.; Guo, L.Y.; Ma, H.J.; Kim, K.B.; Wang, W.M. Thermal analysis of directional pressure annealed Fe78Si9B13 amorphous ribbons. Thermochim. Acta 2018, 661, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.E.; Aronin, A.S.; Stel’mukh, V.A. Crystallization of amorphous Fe85B15 alloy above glass transition temoerature. Fiz. Tverd. Tela 1991, 33, 3570–3577. [Google Scholar]

- Abrosimova, G.E.; Aronin, A.S.; Dobatkin, S.V.; Kaloshkin, S.D.; Matveev, D.V.; Rybchenko, O.G.; Tatiyanin, E.V.; Zverkova, I.I. The formation of nanocrystalline structure in amorphous Fe-Si-B alloy by severe plastic deformation. J. Metastable Nanocryst. Mater. 2005, 24–25, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xu, D.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Liang, T.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, S.; Yang, K.; Zeng, J.; et al. Reversible linear-compression behavior of free volume in a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 144201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Hirata, A.; Liu, P.; Song, S.X.; Tian, Y.; Han, J.H.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.W. Correlation between local structure order and spatial heterogeneity in a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 215501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, A.; Vaidya, M.; Divinski, S.V.; Wilde, G. Impact of cryogenic cycling on tracer diffusion in plastically deformed Pd40Ni40P20 bulk metallic glass. Acta Mater. 2021, 209, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudino, S.; Surreddi, K.B. Shear band morphology and fracture behavior of cold-rolled Zr52.5Ti5Cu18Ni14.5Al10 bulk metallic glass under tensile loading. J. Alloy. Comp. 2017, 708, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderov, D.V.; Churakova, A.A.; Boltynjuk, E.V.; Ubyivovk, E.V.; Astanin, V.V.; Asfandiyarov, R.N.; Valiev, R.Z.; Xioang, W.; Wang, J.T. Observation of shear bands in the Vitreloy metallic glass subjected to HPT processing. J. Alloy. Comp. 2019, 800, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Roddatis, V.; Kenesei, P.; Maaß, R. Shear-band thickness and shear-band cavities in a Zr-based metallic glass. Acta Mater. 2017, 140, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Xu, Y.; Shi, B.; Yu, C.; Hahn, H.; Gleiter, H.; Li, J. High density of shear bands and enhanced free volume induced in Zr70Cu20Ni10 metallic glass by high-energy ball milling. J. Alloy. Comp. 2013, 548, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, G.; Rösner, H. Nanocrystallization in a shear band: An in situ investigation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 251904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Matveev, D.; Pershina, E.; Aronin, A. Effect of treatment conditions on parameters of nanocrystalline structure in Al-based alloys. Mater. Lett. 2016, 183, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronin, A.; Matveev, D.; Pershina, E.; Tkatch, V.; Abrosimova, G. The effect of changes in Al-based amorphous phase structure on structure forming upon crystallization. J. Alloy. Comp. 2017, 715, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Aronin, A.S.; Kir’janov, Y.V.; Matveev, D.V.; Zver’kova, I.I.; Molokanov, V.V.; Pan, S.; Slipenyuk, A. The structure and mechanical properties of bulk Zr50Ti16.5Cu14Ni18.5 metallic glass. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 3933–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Shang, B.; He, Q.; Li, F.; Wang, T.; Wei, D.; Liang, X.; Wu, X.; et al. Fast surface dynamics enabled cold joining of metallic glasses. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, 7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.N.; Suslick, K.S. The Effects of Ultrasound on Crystals: Sonocrystallization and Sonofragmentation. Crystals 2018, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lou, Y.; Xv, S.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J. Rejuvenation of Zr-Based Bulk Metallic Glasses by Ultrasonic Vibration-Assisted Elastic Deformation. Materials 2020, 13, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Volkov, N.; Van Tuan, T.; Pershina, E.; Aronin, A. Cryogenic rejuvenation of Al-based amorphous-nanocrystalline alloys. Mater. Lett. 2019, 240, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Volkov, N.; Pershina, E.; Van Tuan, T.; Aronin, A. Amorphous structure rejuvenation under cryogenic treatment of Al-based amorphous-nanocrystalline alloys. J. Non-Crystal. Solids 2020, 528, 119751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liang, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Gong, F. Sub-second thermoplastic forming of bulk metallic glasses by ultrasonic beating. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lou, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.-C.; Liu, Z. Fast rejuvenation in bulk metallic glass induced by ultrasonic vibration precompression. Intermetallics 2020, 118, 106687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, A.K. Studies in Newtonian Flow. II. The Dependence of the Viscosity of Liquids on Free-Space. J. Appl. Phys. 1951, 22, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Tang, M.B.; Pan, M.X.; Zhao, D.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.H. Calorimetric glass transition in bulk metallic glass forming Zr-Ti-Cu-Ni-Be alloys as a free-volume-related kinetic phenomenon. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 212201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, O.; Inoue, A. Free volume kinetics during sub-Tg structural relaxation of a bulk Pd40Ni40P20 metallic glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 131906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rätzke, K.; Hüppe, P.W.; Faupel, F. Transition from single-jump type to highly cooperative diffusion during structural relaxation of a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 2347–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.H.; Turnbull, D. Molecular Transport in Liquids and Glasses. J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 31, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turnbull, D.; Cohen, M.H. Free-Volume Model of the Amorphous Phase: Glass Transition. J. Chem. Phys. 1961, 34, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y. Release of free-volume bubbles by cooperative rearrangement regions during the deposition growth of a colloidal glass. Nat. Comm. 2017, 8, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangialosia, D.; Alegríaa, A.; Colmenero, J. Effect of nanostructure on the thermal glass transition and physical aging in polymer materials. Prog. Pol. Sci. 2016, 54–55, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egami, T. Structural relaxation in amorphous alloys—Compositional short range ordering. Mater. Res. Bull. 1978, 13, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russew, K.; Sommer, F. Length and density changes of amorphous Pd40Cu30Ni10P20 alloys due to structural relaxation. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2003, 319, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egami, T. Low-Field Magnetic Properties of Amorphous Alloys. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1977, 60, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermeyer, D.; Neuhauser, H. Dilatometric measurements on metallic glass ribbons with a wide glass transition range. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1997, A226–A228, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.S.; Pritchet, W.C. Magnetic Annealing and Directional Ordering of an Amorphous Ferromagnetic Alloy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1975, 34, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, A.R.; Moulec, A.L.; Inoue, A.; Nishiyama, N.; Lupu, N.; Matsubara, E.; Botta, W.J.; Vaughan, G.; Michiel, M.D.; Kvick, Å. Excess free volume in metallic glasses measured by X-ray diffraction. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Fu, Z.D.; Zhang, G.Q.; Hao, X.P.; Jiang, Q.K.; Wang, X.D.; Cao, Q.P.; Franz, H.; Liu, Y.G.; Xie, H.S.; et al. New Class of Plastic Bulk Metallic Glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 075501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, P.; Ramamurty, U. The fracture toughness of bulk metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Huang, L.; Wang, F.; Huang, P.; Lu, T.J.; Xu, K.W. Suppression of annealing-induced embrittlement in bulk metallic glass by surface crystalline coating. Mater. Des. 2016, 109, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, F.X.; Zhang, J.W.; Yu, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J.H.; Liu, R.P.; Xu, Y.F.; Wang, W.K. Influence of pressures on the crystallization process of an amorphous Fe73.5Cu1Nb3Si13.5B9Fe alloy. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 84, 1918–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmani, H.; Grognet, S.; Teillet, S. Crystallization-nitriding process of FeSiB and FeSiBCuNb ribbons: Influence of additive (Cu,Nb) pair and nitrogen on structure, magnetic and magnetostrictive parameters. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2001, 290, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Aronin, A.; Kholstinina, N. On determining the volume fraction of the crystalline phase in amorphous-crystalline alloys. Solid State Phys. 2010, 52, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.H.; Atzmon, M. The effect of compression and tension on shear-band structure and nanocrystallization in amorphous Al90Fe5Gd5: A high-resolution transmission electron microscopy study. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 4095–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.; Rösner, H.; Peterlechler, M.; Wilde, G. Quantitative Measurement of Density in a Shear Band of Metallic Glass Monitored Along its Propagation Direction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 035501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, M.G.; Kursumovic, A. Short-range ordering during structural relaxation of the metallic glass Fe40Ni40B20. Acta Metall. 1982, 30, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronin, A.S.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. On nanovoids formation in shear bands of an amorphous Al-based alloy. Mech. Mater. 2017, 113, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.; Chirkova, V.; Pershina, E.; Volkov, N.; Sholin, I.; Aronin, A. The Effect of Free Volume on the Crystallization of Al87Ni8Gd5 Amorphous Alloy. Metals 2022, 12, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abrosimova, G.; Chirkova, V.; Matveev, D.; Pershina, E.; Volkov, N.; Aronin, A. Influence of a Protective Coating on the Crystallization of an Amorphous Fe78Si13B9 Alloy. Metals 2023, 13, 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/met13061090

Abrosimova G, Chirkova V, Matveev D, Pershina E, Volkov N, Aronin A. Influence of a Protective Coating on the Crystallization of an Amorphous Fe78Si13B9 Alloy. Metals. 2023; 13(6):1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/met13061090

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbrosimova, Galina, Valentina Chirkova, Danila Matveev, Elena Pershina, Nikita Volkov, and Alexandr Aronin. 2023. "Influence of a Protective Coating on the Crystallization of an Amorphous Fe78Si13B9 Alloy" Metals 13, no. 6: 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/met13061090