Cooperative Learning of Seiryu-Tai Hayashi Learners for the Hida Furukawa Festival in Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background Information

1.2. Research Motivation

1.3. Research Purpose

1.4. Literature Review

1.4.1. Cooperative Learning

- Positive interdependence: To achieve personal goals, group members should accomplish shared goals together. This pushes group members to cooperate to achieve shared goals, and members need to depend on each other, encourage, share, and assist others in learning. Conversely, as the group achieves goals in a manner opposed to personal goals, passive dependence occurs, which is also called competition.

- Individual accountability: Cooperative learning emphasizes group performance and individual accountability. The personal accountability of learners decides whether a group’s shared goal is achieved; therefore, personal learning and general performance are features of cooperative learning.

- Promotive interaction: Group members learn with each other, sharing, encouraging, or even assisting with members’ learning. This helps enhance member accountability through interacting to increase the ability to achieve shared goals.

- Social skills: To accomplish shared goals, members must have skills such as communication, respect, and trust-building. They have to identify, trust, support, and communicate with each other to solve shared problems.

- Group processing: Group members discuss how well they are achieving their goals and adjust group members’ performance to maintain effective working relationships to accomplish shared goals.

1.4.2. Social Support

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Materials

2.2.1. Observation

2.2.2. Interviewing

2.2.3. Grounded Theory

2.3. Field of Research

3. Results

3.1. Seiryu-Tai Hayashi Group in the Furukawa Festival

3.1.1. Hayashi Instructors

3.1.2. Hayashi Learners

3.2. Training Etiquette and Skills Practice: Following Norms of Hayashi Learning, Then Cultivating Skills

3.2.1. Taking Norms as Hayashi Cooperative Learning Premise

- Safety request: Wear reflective strap on the way to training and back.

- Punctuality request: Be on time. There are seldom latecomers.

- Politeness request: Greet elders or companions. Say “thank you” to instructors after learning, and instructors will say “well done” to learners. Before going home, learners line up for snacks, and then stand in front of the door to bow toward the interior and say “thank you, I have to go home first” before leaving the practice room.

- Order request: Bicycles need to be parked in an orderly manner in front of the stall warehouse. Take off shoes when entering front door of hall and put shoes into the shoe cabinet with shoe toes facing interior or put on the ground with shoe toes facing the entrance. Help to arrange disordered shoes actively and put folded coats neatly on the floor.

- Request for senior schoolmates: Third-grade secondary school students are responsible for mustering everyone.

- Quiet request: Be quiet when learning, and do not speak loudly during breaktime. Do not run in the hall (Figure 8).

3.2.2. Norms of Shoes Arrangement in Learning Space

3.2.3. Arranging Instruments Spontaneously That Are Not Included in Hayashi Norms

3.2.4. Learners Who Follow Life Norms Accurately

3.2.5. Results Summary

- Positive interdependence: Learners apply norms of common maintenance in learning, and Hayashi performance in the Furukawa Festival is the shared goal to positively learn the arts of Hayashi with each other.

- Individual accountability: Following the norms of Hayashi learning is the primary issue, followed by improving in the arts of Hayashi.

- Promotive interaction: Following the norms of Hayashi learning together promotes interaction between learners. If someone breaks the rules, the person will lose the ability to learn and to have interactions with companions. Learners increase interaction with elders during the learning process.

- Social skills: Following Hayashi learning norms increases social communication abilities with elders and companions. Spending time with learning companions promotes social skills and interpersonal communication.

- Group processing: Experiencing following the learning norms of Hayashi and the process of Hayashi learning with learning companions.

3.3. Demonstration and Imitation: Learning Process without Hayashi

3.3.1. Hayashi Learning of Tacit Knowledge without Notation

Tacit Knowledge Passes Down Hayashi

Learning in Groups by Instrument

Hayashi Is a Cooperative Performance Showing Internal Tacit Agreement

3.3.2. Identifying Learners behind on the Learning Schedule

3.3.3. Results Summary

- Positive interdependence: Instructors demonstrated playing cymbals, taiko drums, and flutes, and then learners imitated rhythm and melodies using only their hearing and vision. Instructors went on an inspection tour and corrected learners immediately if they observed mistakes so as to ensure the performance would be harmonious.

- Individual accountability: To be harmonious, participants learned the ensemble skills in separate same-instrument groups. Both instructors and third-grade secondary school students demonstrated, and learners improved personal skills by imitation and while playing in the instrumental ensemble.

- Promotive interaction: Instructors and third-grade secondary school students demonstrated how to play, and learners observed. Instructors went on an inspection tour to examine everyone playing and to provide instruction.

- Social skills: Every learner learned their personal instrument as well as social skills during cooperative performance. Learners learned social skills through the instruction from instructors and senior learners.

- Group processing: Learners learned Hayashi skills without written notation through instructor and senior learner demonstration.

3.4. Instruction and Accompanyment: Elders Communicated Norms, Skills Demonstration, Comfort, and Rewards

3.4.1. Elders Supporting Hayashi Learning in Action

3.4.2. Elders Practice Etiquette Themselves and Pay Attention to Hayashi Learning

Instructors Set Practice Norms Examples

The Stall Chief Who Took a Formal Sitting Posture Toward Learners

3.4.3. Interaction and Feedback with Thanks

3.4.4. Results Summary

- Positive interdependence: The learner and the instructor have a dependency relationship between learning and responsibility. Organize peer learning for other elders, verbal encouragement and snack rewards to form emotional dependence with learners.

- Individual accountability: Performing as part of the Furukawa Festival was a shared goal to practice ensemble coordination and improved Hayashi skill so that elders would not be disappointed.

- Promotive interaction: Elders in the organization provided supportive relationships by helping learners who were struggling go learn. The chief of the hall assumed a formal sitting posture to enhance learners’ accountability, and instructors supervised the habits of Hayashi learning and skills. They felt grateful for each other.

- Social skills: Social skills improved interactions with elders and group members through instruction and support, and they provided feedback regarding social skills with gratefulness.

- Group processing: Learning companions were accountable for the communal learning of their organization, accompanied by the elders in the organization.

3.5. Experience and Feeling: Children Experience the Atmosphere of Hayashi Learning

3.5.1. Playing with Instruments before Practice to Feel the Hayashi Atmosphere

3.5.2. Too Young but Wants to Participate in Hayashi Learning

3.5.3. Results Summary

- Positive interdependence: Children were brought to watch Hayashi learning by elders, and they experienced the Hayashi atmosphere. Child J joined the cymbals group despite being too young, but instructors comforted him and expressed their wish for him to join Hayashi learning the following year.

- Individual accountability: Children experienced the atmosphere of Hayashi learning. Intruding children like Child J were accepted but Hayashi learning practice continued.

- Promotive interaction: Children and infants were especially quiet when hearing the Hayashi performance. Child J, who was a third-grade elementary school student, was influenced by his father’s participation and wanted to join Hayashi practice. Instructors gave him a snack to comfort and encourage Child J to join next year.

- Social skills: Making babies and children feel interest in Hayashi and being friendly and tolerant of Child J.

- Group processing: Being watched by babies brought by their families to the practice room and Child J who intruded repeatedly into cymbals practice.

3.6. Others and Interaction: Experience of Different Cultures

3.6.1. English Narration Brought Deeper Understanding of Different Cultures

3.6.2. Influence, Encouragement, and Participation Positively Affecting Interaction with Different Cultures

3.6.3. Hayashi Learning Promoted the Interaction of Different Cultures

3.6.4. Results Summary

- Positive interdependence: The senior learners of the junior high school were not influenced by the foreign visitors; the experienced helped the junior learners from elementary school to manage their reactions. Learners were able to adapt in advance to the tourists who would be present during Hayashi performance. Instructors did not reprimand the distracted learners but comforted them with words.

- Individual accountability was not influenced by foreign visitors and participation. The visitors were given the opportunity to experience Hayashi with hearing and sight, allowing people of different cultures to learn about Japanese festival culture.

- Promotive interaction: Different cultures interact at festivals due to the foreign visitors. Instructors comforted distracted learners with words, tourists warmly appreciated and applauded the learners, and then learners responded with shy smiles.

- Social skills: Experiencing different cultures through interaction with foreign visitors and adapting to the environment and etiquette with tourists.

- Group processing: Being visited by foreign visitors, the junior learners were distracted and then comforted, and Hayashi learning was explained in English by hotel staff.

4. Discussion

4.1. People, Events, Time, Place, and Objects in Hayashi Cooperative Learning

4.2. Relationship between Hayashi Cooperative Learning and Roles

4.3. The Cultural Function of a Festival

- To pass on traditions: The repeated organization of annual festivals is how the cultural context of a traditional culture and an aesthetic form are transmitted to future generations.

- To improve teamwork: Festival participants identify with each other, creating a spirit of community teamwork.

- To shape local characteristics: The Okoshi Daiko performance of half-naked men is the only unique characteristic of the Furukawa festival, but this uniqueness is integral to the self-identity of this location.

- To strengthen art preference: The Yatai Parade is also called a moving museum. The Yatai is a small wooden structure; the marionettes and children’s kabuki performance on the Yatai floats have the aesthetics of a drama performance. Hayashi performers provide musical performance and the variety of costumes worn by participants at the festival, and the Furukawa festival, are a manifestation of the beauty of art.

5. Conclusions

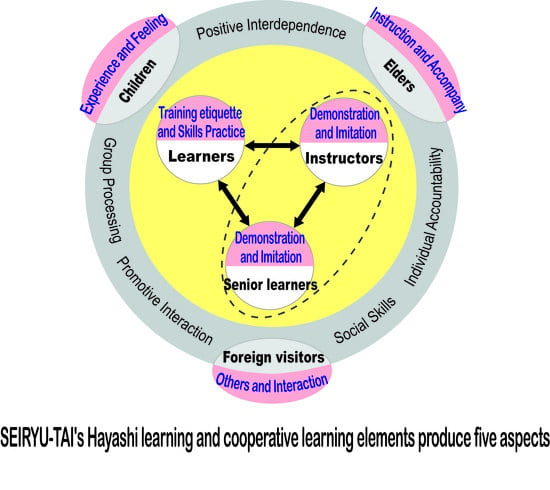

5.1. Five Aspects of Seiryu-Tai’s Cooperative Hayashi Learning

5.2. Positive Interdependence Influence on Hayashi Learning Process: Deep Interdependence in the Core of the Learning Circle, Followed by Guarding and Immersion

5.3. Individual Accountability Influence on Hayashi Learning Process: Achievement of Following Norms, Enhancing Skills, and Tacit Agreement within the Instrumental Ensemble

5.4. Promotive Interaction Influences the Hayashi Learning Process: Five Interactive Influence Types

5.5. Influence of Social Skills on Hayashi Learning Process: Playing, Performing, Senior, and Foreign

5.6. Group Processing Influence on the Hayashi Learning Process: Joint Forming of Hayashi Learning Circle by Learners, Instructors, Senior Learners, Elders, Youths, and Foreign Visitors

5.7. Several Festival Organization Learning Circles Form the Basic Social Support of the Furukawa Festival

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, C.W. Rediscovery of Soul and Beauty: Japanese Festival, 1st ed.; Hiking culture: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami, M. Hoko Event and Local Residents of Kyoto Gion Festival: Their Organization and Spirit. Inf. Mag. CEL 2012, 100, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.H. A Circulatory System of Intangible Culture Heritage in Community Empowerment and Cultural and Creative Industry—The Comparison of Folk Festivals between Taiwan and Japan (II); NSC Project Reports: Taipei, Taiwan, 2013; (NSC 102-2410-H-224-024), Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sannino, A.; Engeström, Y.; Lemos, M. Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 25, 599–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.T.; Johnson, D.W. Cooperation and the use of technology. Handb. Res. Educ. Commun. Technol. 1996, 30, 785–811. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/243671476 (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Britton, J. Perspectives on small group learning: Theory and practice. In Research currents: Second thoughts on Learning; Brubacher, M., Payne, R., Richett, K., Eds.; Rubicon: Oakville, ON, USA, 1990; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.T.; Johnson, D.W. Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning, 3rd ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Theoretical approaches to cooperative learning. In Collaborative Learning: Developments in Research and Practice; Nova: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. The use of cooperative procedures in teacher education and professional development. J. Educ. Teach. 2017, 43, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Lin, P.H. Cooperative Learning, 1st ed.; Wu-Nan Book Inc.: Taipei City, Taiwan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.T.; Johnson, D.W. Action research: Co-operative learning in the science classroom. Sci. Child. 1986, 24, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Reber, A.S. The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers; Harper & Row: Chicago, IL, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, W.B. The Coping Effect of Social Support: A Critical Review. J. Soc. Sci. Philos. 2001, 11, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, G.; Killilea, M. Support System and Mental Help: Multidisciplinary Explorations, 1st ed.; Grune and Stratton: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keting, Z. Ethnography and Observation Research Act; Angrosino, M., Ed.; Weber Culture: Taipei City, Taiwan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, R.G. (Ed.) Field Research: A Sourcebook and Field Manual; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; Volume 4, Available online: https://www.routledge.com/ (accessed on 29 September 2019). (First Published in 1982. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an inform company.).

- Moriuchi, E.; Basil, M. The Sustainability of Ohanami Cherry Blossom Festivals as a Cultural Icon. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, W. Ethnography; Fetterman, D.M., Ed.; Yangzhi Culture: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. 2011. Available online: https://scholar.google.com.tw/scholar?cluster=4884479584332384561&hl=zh-TW&as_sdt=0,5&as_vis=1 (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Cole, M. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| Time and Event | Text Notes Taken Onsite | Open Coding |

|---|---|---|

| 18:45 Shoes neatly arranged in the genkan (entryway) A01 | The shoe cupboards in the entryway of the Seiryu assembly hall were filled with shoes all aligned with the toes pointing inward (A01-1). In total, 85% of the shoes were children’s shoes. The shoe cupboards were full. Some of the shoes were placed in the entryway in rows with the toes pointing out toward the door (A01-2). Children on the second floor of the assembly hall were making a ruckus, and a few children entered the hall, saying the greeting “kon’nichiwa”, (A01-3) and quickly ran up to the second floor. Some children remained in the entryway to tidy up the shoes that had not been organized properly (A01-4). | A01-1. Learners remove their shoes and place them in the shoe cupboard with toes pointing inward. A01-2. Learners remove their shoes and place them on the floor with toes pointing out toward the door. A01-3. Learners greet anyone that walks pass them. A01-4. A few learners help to neatly arrange disorganized shoes. |

| 18:50 Support of the Seiryu-tai members A02 | The adults began arriving. All of them were members of the Seiryu-tai group (A02-1) and included a Hayashi instructor, staff members of the Seiryu-tai group for this year’s Furukawa festival, older adults, a grandmother carrying her two-year old grandson to observe the practice, and a young father holding his baby (A02-2) (A02-3). They were all in the tatami training room on the second floor to watch the practice. | A02-1. Numerous older adults went to the training room out of concern for the Hayashi learners. A02-2. An infant was brought along with a family member to experience the training atmosphere. A02-3. A baby was brought along by his father to listen to the training. |

| Excerpt No. | Transcript | Open Coding |

|---|---|---|

| ina-1 | We hand out snacks to children at the end of every day as a reward for their hard work. The snacks are paid for by the organization, but sometimes they are provided by other members (ina-1-1). | Seniors provide tangible rewards (ina-1-1) |

| ina-2 | Almost all children within the organization attend. We also notified them in writing of the time and venue (ina-2-1), even though they know they are supposed to come. We have a few new learners this year who are fourth-year elementary school students. They come to class themselves, although it is their first time. Everyone knows these things (ina-2-2). | Official notice (ina-2-1) Learners are well informed (ina-2-2) |

| ina-3 | No, we have not used musical scores for a long time (ina-3-1). This was how I learned 60 years ago. I did not learn music or theory. Learn for long enough and [you] master it [a skill] (ina-3-2). [I] was interested so [I] started teaching. It has been 50 years. I have been finding ways to teach. I use my instinct. Listen long enough, and [you] know the beats and rhythms. This is experience (ina-3-3). It has nothing to do with my job. | Learning without scores and passing on this approach to future generations (ina-3-1) Intuitive learning (ina-3-2) Experience is knowledge (ina-3-3) |

| Date | Date Numbering | Paragraph Numbering | Coding Numbering | Subcategory | Main Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 1 | A | A01, 02, ⋯ | A01-1, A01-2, ⋯ | AVC-01, AVC-02, ⋯ | VC-01, VC-02⋯ |

| April 8 | H | H01, 02, ⋯ | H01-1, H01-2, ⋯ | HVC-01, HVC-02, ⋯ | |

| April 15 | O | O01, 02, ⋯ | O01-1, O01-2, ⋯ | OVC-01, OVC-02, ⋯ |

| Numbering | Status | Sequence of Same Status | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEA | SEI RIYUU TAI | Seiryu-tai | Main stall chief |

| INA | Instructor | Instructor A | Main instructor |

| INB | Instructor | Instructor B | Secondary instructor |

| INC | Instructor | Instructor C | Younger instructor |

| LEA | Learner | Learner A | A girl in sixth grade of elementary school |

| LEB | Learner | Learner B | A boy in fourth grade of elementary school |

| LEC | Learner | Learner C | A boy in fourth grade of elementary school |

| ELA | Elder | Elder A | A woman about 60 years old who brought snacks for learners |

| ELB | Elder | Elder B | A woman about 90 years old |

| ELC | Elder | Elder C | A man about 70 years old |

| ELD | Elder | Elder D | A man about 65 years old who lives with a 3-year-old grandson |

| ELJ | Elder | Elder J | A man about 35 years old and whose first letter of family name is J, child J’s father |

| TOA | Tourist | Tourist A | From Australia, having a trip with family |

| Status Numbering | Coding Numbering | Note |

|---|---|---|

| SEA | SEA-1-1 | First coding in the first paragraph of interview with Seiryu-tai’s main chief |

| INB | INB -1-1 | The first coding in the first paragraph of interview with instructor B |

| LEA | LEA -1-1 | The first coding in the first paragraph of interview with learner A |

| ELC | ELC -1-1 | The first coding in the first paragraph of interview with elder C |

| TOA | TOA -1-1 | The first coding in the first paragraph of interview with tourist A |

| Training Etiquette and Skills Practice | |

|---|---|

| Description of Specific Behaviors | Several specific behavioral requirements must be fulfilled when children are learning to play a musical instrument: (1) Safety: Learners must wear a reflective belt when coming to practice. (2) Punctuality: Learners must be punctual. Tardiness is almost nonexistent. (3) Manners: Learners greet elders and their peers and say “thank you” to their instructor, who replies, “thank you for your hard work.” At the end of practice, students line up to collect snacks. Before leaving the practice room, they stand by the door, facing the room and say, “thank you; I am leaving first.” (4) Order: Bicycles must be parked properly in front of the Yatai warehouse. Shoes must be removed before entering the assembly hall and stored in the shoe cupboard with toes pointing inward or placed flat on the floor with toes pointing out toward the door. Learners must voluntarily help to rearrange disorganized shoes and neatly fold and store their jackets. (5) Requirements for senior learners: Third-year junior high school students are in charge of assembling everyone. (6) Instrument care: Before practice commences, third-year junior high school students help bring out the musical instrument boxes and lay them out in an orderly fashion; at the end of practice, fourth-year elementary school students put the cymbals back in a wooden box. Flute learners, including sixth-year elementary and first- to third-year junior high school students, must first wipe down and clean the flute they used and then return it to their flute bag. Flutes for use by all must be neatly placed in the wooden flute box. (7) General rules: Learners must be quiet during practice, keep their voice down during breaks, and not run around the hall during breaks. |

| Training Etiquette and Skills Practice | |

|---|---|

| Positive Interdependence | (1) Follow the rules and work together to keep the group in order: Follow the rules and behave like everyone else in an environment in which everyone follows the rules of everyday life; for example, arrive on time, remove shoes before entering the hall and place them neatly in the entryway, and greet adults when you see them. (2) Commit to learning with the goal of performing with teammates: Keep up to speed in learning Hayashi skills to ensure a successful performance during the festival. |

| Individual Accountability | Skill improvement and compliance (1) Be accountable for gradual self-improvement in Hayashi skills. (2) Be accountable by complying fully with the Hayashi learning rules. |

| Promotive Interaction | (1) Enforcing the rules of everyday life facilitates positive interactions: Manner, order, assistance by senior learners, and instrument care, among other matters, help improve interactions. (2) Violators cannot stay in the circle of interaction: Those who break the rules are banned from practice. (3) Learning behavior optimizes interaction with older adults: Hayashi learners are valued by senior members of the organization. |

| Social Skills | Greeting skills, social skills to play with others, and skills to comply with the social rules (1) Manner can positively affect social interaction. (2) Chat or play with other learners during breaks. (3) Queue up to collect snacks from the instructor at the end of practice and say thank you. |

| Group Processing | The process of learning and obeying rules together (1) Acquire Hayashi skills together. (2) Obey the Hayashi learning rules together. (3) Comply with the Hayashi learning rules in order to acquire Hayashi skills. (4) All learners should be seated seiza-style at 19:00 sharp and say to the instructor “please teach me” before they begin learning. At 20:00, learners should sit seiza-style and say to the instructor “thank you for teaching me” before the session is concluded. |

| Region of Seiryu-tai | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Katahara-cho, Furukawa-cho | 100 | 112 | 212 |

| Higashimachi, Furukawa-cho | 76 | 68 | 144 |

| 1-Chome, Wakamiya, Furukawa-cho | 125 | 136 | 261 |

| Kanamoricho, Furukawa-cho | 176 | 179 | 355 |

| Tonomachi, Furukawa-cho | 219 | 236 | 455 |

| Total | 696 | 731 | 1427 |

| Seiryu-Tai | Boys | Girls | Member Statistics | Learning Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Third grade of secondary school | 6 | 3 | 9 | Flute |

| Second grade of secondary school | 5 | 1 | 6 | Flute |

| First grade of secondary school | 5 | 1 | 6 | Flute |

| Sixth grade of elementary school | 7 | 3 | 10 | Flute |

| Fifth grade of elementary school | 6 | 1 | 7 | Taiko dram and cymbals |

| Fourth grade of elementary school | 6 | 3 | 9 | Cymbals |

| Total | 35 | 12 | 47 |

| Element of Cooperative Learning | Cultivation and Skill Practice |

|---|---|

| Positive interdependence | Keep following norms and performing together is a shared goal to learning skills. |

| Individual accountability | Follow norms and improve art skill. |

| Promotive interaction | Life rules promote interaction. Cannot remain in the circle if breaking the rules. Learning behavior optimizes interaction with elders. |

| Social skills | Follow social etiquette, improve communication social skills, and ability to play together. |

| Group processing | Experience following learning norms and learning together. |

| Five Elements of Cooperative Learning | Demonstration and Imitation |

|---|---|

| Positive interdependency | Learning dependency includes: demonstration, imitation, correction, and cooperative learning. |

| Individual accountability | Senior learners have to demonstrate not only their skills but also cooperative learning of the instrumental ensemble. |

| Promotive interaction | Interaction of demonstration and imitation, and interaction with instructors who corrected skills. |

| Social skills | Learning social skills in demonstration and cooperative learning. |

| Group processing | Playing without notation. |

| Five Elements of Cooperative Learning | Instruction and Accompanying |

|---|---|

| Positive interdependence | Dependencies of learning, accountability, and emotion. |

| Individual accountability | Improving skill and coordinated play with help from elders. |

| Promotive interaction | Interaction with elders’ support, teaching, instructional supervision on norms and skill, and being grateful for each other. |

| Social skills | Social skills from interacting with elders, society, and being thankful. |

| Group processing | Learning accountability from elders and being supported. |

| Five Elements of Cooperative Learning | Experience and Feel |

|---|---|

| Positive interdependence | Interdependence of experience and feeling. |

| Individual accountability | Letting babies feel the Hayashi atmosphere and forgiving Child J for intruding into Hayashi practice. |

| Promotive interaction | Interaction between babies and Hayashi, and with people intruding. |

| Social skills | Social skills of babies experiencing in Hayashi atmosphere and a child intruding. |

| Group processing | Jointly addressing the intrusion of unqualified learners. |

| Five Elements of Cooperative Learning | Others and Interaction |

|---|---|

| Positive interdependence | Mutual dependence. |

| Individual accountability | Senior learners were not influenced by external factors, tourists felt the charm of Hayashi, and the interaction of different cultures at the festival. |

| Promotive interaction | Interaction with different cultures, applause, and smiles. |

| Social skills | Social skills of locals and non-Japanese visitors. |

| Group processing | Group processing of being with non-Japanese visitors. |

| Related Parties | Five Aspects of Seiryu-Tai’s Hayashi Cooperative Learning | Five Elements of Cooperative Learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Interdependence | Individual Accountability | Promotive Interaction | Social Skills | Group Processing | ||

| Instructors Learners | Training etiquette and skills practice: 1. Taking norms as Hayashi cooperative learning premise 2. Norms of shoes arrangement in learning space 3. Arranging instruments spontaneously that are not included in Hayashi norms 4. Learners who follow life habits accurately | Keep following norms in order and take performing together as a shared goal for learning skills | Follow norms and improve skill and ability | Life rules promote interaction Cannot stay in the circle if breaking rules Learning behavior optimizes interaction with elders | Follow social etiquette Improve communication social skills Ability to play together | Experience of following learning norms and learning together |

| Instructors Senior learners Learners | Demonstration and imitation: 1. Hayashi learning of tacit knowledge without notation 2. Reprimanding learners for being behind the learning schedule 3. Ignoring reprimanding temporarily | Demonstration dependency Imitation dependency Correction dependency Cooperative learning dependency | Senior learners have to demonstrate their skills as well as cooperative learning for the instrumental ensemble | Interaction of demonstration and Imitation Interaction with instructors who corrected skills | Learning social skills in demonstration Cooperative learning | Learning process without music score |

| Instructors Senior learners Learners Elders | Instruction and accompaniment: 1. Elders who support Hayashi learning in action 2. Elders practice etiquette themselves and pay attention to Hayashi learning 3. Interaction and feedback with thanks | Dependency of learning Accountability dependency Accompanying dependency | Improving skill Coordinated play of instruments to elders | Interaction of elders’ support and accountability for learning Instructional supervision of norms and skill Being grateful for each other | Social skill of interacting with elders Social skills with the community Social skill of being thankful | Learning process entrusted to elders in terms of learning responsibilities and companionship |

| Instructors Senior learners Learners Elders Child | Experience and feeling: 1. Playing with instruments before practice to feel Hayashi atmosphere 2. Too young but desire to participate in Hayashi learning | Interdependence of experience and feeling | Letting babies and children experience Hayashi atmosphere Forgiving Child J for intruding into Hayashi learning | Interaction between children/babies and Hayashi, and with people intruding | Immersing children in the environment of Hayashi Learning Social skills to tolerate trespassers | Jointly addressing unqualified learners intruding in practice |

| Instructors Senior learners Learners Elders Child Foreign visitors | Others and interaction: 1. English narration brought deeper understanding of different cultures 2. Influence, encouragement, and participation positively affect interaction with different cultures 3. Hayashi learning promotes interaction with different cultures | Interaction with different cultures | Senior learners were not influenced by external factors Tourists experience the charm of Hayashi and interaction Different cultures attend the festival | Interaction with different cultures, applause and smiles | Social skills of locals and foreign visitors | Group processing of being with foreign visitors |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, S.-H.; Chan, H.-Y. Cooperative Learning of Seiryu-Tai Hayashi Learners for the Hida Furukawa Festival in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104292

Hwang S-H, Chan H-Y. Cooperative Learning of Seiryu-Tai Hayashi Learners for the Hida Furukawa Festival in Japan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104292

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Shyh-Huei, and Hsu-Ying Chan. 2020. "Cooperative Learning of Seiryu-Tai Hayashi Learners for the Hida Furukawa Festival in Japan" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104292