The Confusion Assessment Method Could Be More Accurate than the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale for Diagnosing Delirium in Older Cancer Patients: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellelli, G.; Brathwaite, J.S.; Mazzola, P. Delirium: A Marker of Vulnerability in Older People. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 626127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.S.; Fong, T.G.; Hshieh, T.T.; Inouye, S.K. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, S.H.; Lawlor, P.G.; Ryan, K.; Centeno, C.; Lucchesi, M.; Kanji, S.; Siddiqi, N.; Morandi, A.; Davis, D.H.J.; Laurent, M.; et al. Delirium in Adult Cancer Patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, iv143–iv165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.C.; Tseng, P.T.; Tu, Y.K.; Hsu, C.Y.; Liang, C.S.; Yeh, T.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Chu, C.S.; Matsuoka, Y.J.; Stubbs, B.; et al. Association of Delirium Response and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for the Management and Prevention of Delirium: A Network Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, M.B.; Wee, I.; Agar, M.; Vardy, J.L. The Detection of Delirium in Admitted Oncology Patients: A Scoping Review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Velthuijsen, E.L.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Mulder, W.J.; Verhey, F.R.J.; Kempen, G.I.J.M. Detection and Management of Hyperactive and Hypoactive Delirium in Older Patients during Hospitalization: A Retrospective Cohort Study Evaluating Daily Practice. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hussein, M.; Hirst, S.; Salyers, V. Factors That Contribute to Underrecognition of Delirium by Registered Nurses in Acute Care Settings: A Scoping Review of the Literature to Explain This Phenomenon. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Delirium Association and American Delirium Society. The DSM-5 Criteria, Level of Arousal and Delirium Diagnosis: Inclusiveness Is Safer. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ros, P.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M. Delirium Assessment in Older People in Emergency Departments. A Literature Review. Diseases 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.K.; van Dyck, C.H.; Alessi, C.A.; Balkin, S.; Siegal, A.P.; Horwitz, R.I. Clarifying Confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A New Method for Detection of Delirium. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 113, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart, W.; Rosenfeld, B.; Roth, A.; Smith, M.J.; Cohen, K.; Passik, S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1997, 13, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neefjes, E.C.W.; Van Der Vorst, M.J.D.L.; Boddaert, M.S.A.; Verdegaal, B.A.T.T.; Beeker, A.; Teunissen, S.C.C.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Zuurmond, W.W.A.; Berkhof, J.; Verheul, H.M.W. Accuracy of the Delirium Observational Screening Scale (DOS) as a Screening Tool for Delirium in Patients with Advanced Cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Puchades-García, A.; Pérez-Ros, P. Accuracy of Delirium Screening Tools in Older People with Cancer—A Systematic Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, A.; Sattar, S.; Nightingale, G.; Saracino, R.; Skonecki, E.; Trevino, K.M. A Practical Guide to Geriatric Syndromes in Older Adults With Cancer: A Focus on Falls, Cognition, Polypharmacy, and Depression. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, e96–e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karuturi, M.; Wong, M.L.; Hsu, T.; Kimmick, G.G.; Lichtman, S.M.; Holmes, H.M.; Inouye, S.K.; Dale, W.; Loh, K.P.; Whitehead, M.I.; et al. Understanding Cognition in Older Patients with Cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extermann, M. Older Patients, Cognitive Impairment, and Cancer: An Increasingly Frequent Triad. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Network JNCCN 2005, 3, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaedal, J. Does My Older Cancer Patient Have Cognitive Impairment? J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2018, 9, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelstein, A.; Pergolizzi, D.; Alici, Y. Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 11, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelstein, A.; Alici, Y. Diagnosing and Managing Delirium in Cancer Patients. Oncology 2017, 31, 686–693. [Google Scholar]

- Cascella, M.; Di Napoli, R.; Carbone, D.; Cuomo, G.F.; Bimonte, S.; Muzio, M.R. Chemotherapy-Related Cognitive Impairment: Mechanisms, Clinical Features and Research Perspectives. Recenti. Prog. Med. 2018, 109, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.; Joly, F.; Vardy, J.; Ahles, T.; Dubois, M.; Tron, L.; Winocur, G.; De Ruiter, M.B.; Castel, H. Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment: An Update on State of the Art, Detection, and Management Strategies in Cancer Survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Battisti, N.M.L.; Padgett, L.; Sleight, A.G.; Abdallah, M.; Newman, R.; Van Dyk, K.; Covington, K.R.; Williams, G.R.; van den Bos, F.; et al. Embracing the Complexity: Older Adults with Cancer-Related Cognitive Decline-A Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology Position Paper. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2020, 11, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Mu, Y.; Wu, T.; Xu, Q.; Lin, X. Risk Factors for Delirium in Advanced Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 62, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, A.; Allore, H.; Cohen, H.J.; Mohile, S.G.; Williams, G.R.; Chapman, A.; Extermann, M.; Olin, R.L.; Targia, V.; Mackenzie, A.; et al. Geriatric Assessment with Management in Cancer Care: Current Evidence and Potential Mechanisms for Future Research. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Williams, M.; Mogan, C.; Harrison Dening, K. Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults with Cancer. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat. Care 2021, 15, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.J.; Hahm, B.-J.; Shim, E.-J. Screening and Assessment Tools for Measuring Delirium in Patients with Cancer in Hospice and Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2021, 24, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahona, E.; Pinhao, R.; Galindo, V.; Noguera, A. The Diagnostic Sensitivity of the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale—Spanish Version. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz García, V.; López Pérez, M.; Zuriarrain Reyna, Y. Prevalencia de delirium mediante la escala Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) en pacientes oncológicos avanzados ingresados en una Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos. Factores de riesgo, reversibilidad y tratamiento recibido. Med. Paliativa 2018, 25, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, J.-D.; Gagnon, P.; Harel, F.; Tremblay, A.; Roy, M.-A. Fast, Systematic, and Continuous Delirium Assessment in Hospitalized Patients: The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2005, 29, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, P.G.; Nekolaichuk, C.; Gagnon, B.; Mancini, I.L.; Pereira, J.L.; Bruera, E.D. Clinical Utility, Factor Analysis, and Further Validation of the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale in Patients with Advanced Cancer: Assessing Delirium in Advanced Cancer. Cancer 2000, 88, 2859–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klankluang, W.; Pukrittayakamee, P.; Atsariyasing, W.; Siriussawakul, A.; Chanthong, P.; Tongsai, S.; Tayjasanant, S. Validity and Reliability of the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale-Thai Version (MDAS-T) for Assessment of Delirium in Palliative Care Patients. Oncologist 2020, 25, e335–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Kim, Y.J.; Suh, S.W.; Son, K.-L.; Ahn, G.S.; Park, H.Y. Delirium and Its Consequences in the Specialized Palliative Care Unit: Validation of the Korean Version of Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Fick, D.M. Recognition of Delirium Superimposed on Dementia: Is There an Ideal Tool? Geriatrics 2023, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T.G.; Hshieh, T.T.; Tabloski, P.A.; Metzger, E.D.; Arias, F.; Heintz, H.L.; Patrick, R.E.; Lapid, M.I.; Schmitt, E.M.; Harper, D.G.; et al. Identifying Delirium in Persons With Moderate or Severe Dementia: Review of Challenges and an Illustrative Approach. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 30, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Salas, B.; Trujillo-Martín, M.M.; Martínez del Castillo, L.P.; García-García, J.; Pérez-Ros, P.; Rivas-Ruiz, F.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Multicomponent Interventions for the Prevention of Delirium in Hospitalized Older People: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2947–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Salas, B.; Trujillo-Martín, M.M.; Del Castillo, L.P.M.; García, J.G.; Pérez-Ros, P.; Ruiz, F.R.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Pharmacologic Interventions for Prevention of Delirium in Hospitalized Older People: A Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 90, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Delirium (n = 47) n (%) * | No Delirium (n = 28) n (%) * | Total (n = 75) n (%) * | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 71.2 (4.2) | 72.2 (3.9) | 71.6 (4.1) | 0.022 § |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 26 (55.3) | 13 (46.4) | 39 (52.0) | 0.46 ‡ |

| Female | 21 (44.8) | 15 (53.6) | 36 (48.0) | |

| Tumor site | ||||

| Breast | 4 (8.5) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (6.7) | 0.75 ‡ |

| Skin | 5 (10.6) | 4 (14.3) | 9 (12.0) | |

| Digestive cancer | 14 (29.8) | 6 (21.4) | 20 (26.7) | |

| Hematological cancer | 11 (23.4) | 8 (28.6) | 19 (25.3) | |

| Lung | 11 (23.4) | 6 (21.4) | 17 (22.7) | |

| Gynecological cancer | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Prostate | 2 (4.3) | 2 (7.1) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Dementia | 45 (95.7) | 23 (82.1) | 68 (90.7) | 0.68 ‡ |

| Incontinence | 43 (91.5) | 22 (78.6) | 65 (86.7) | 0.11 ‡ |

| Urinary | 18 (38.3) | 6 (21.4) | 24 (32.0) | 0.15 ‡ |

| Mixed | 25 (53.2) | 16 (57.1) | 41 (54.7) | |

| Use of bladder catheter | 17 (36.2) | 6 (21.4) | 23 (30.7) | 0.18 ‡ |

| Urinary infection in previous 6 months | 7 (14.9) | 7 (25.0) | 14 (18.7) | 0.28 ‡ |

| Kidney failure | 4 (8.5) | 4 (14.3) | 8 (10.7) | 0.43 ‡ |

| Falls in previous month | 3 (6.4) | 7 (25.0) | 10 (13.3) | 0.022 ‡ |

| Dysphagia | 24 (51.1) | 5 (17.9) | 29 (38.7) | 0.040 ‡ |

| Hospitalization in previous 6 months | 43 (91.5) | 24 (85.7) | 67 (89.3) | 0.58 ‡ |

| ED visit in previous 6 months | 43 (91.5) | 25 (89.3) | 68 (90.7) | 0.75 ‡ |

| Drug treatments | ||||

| Number of daily drugs, mean (SD) | 11.8 (2.3) | 10.9 (3.0) | 11.5 (2.6) | 0.14 § |

| Anticholinergics | 45 (95.7) | 24 (85.7) | 69 (92.0) | 0.12 ‡ |

| Anxiolytics | 14 (29.8) | 10 (35.7) | 24 (32.0) | 0.56 ‡ |

| Antidepressants | 6 (12.8) | 1 (3.6) | 7 (9.3) | 0.19 ‡ |

| Neuroleptics | 18 (38.3) | 12 (42.9) | 30 (40.0) | 0.70 ‡ |

| Variables | Delirium (n = 47) | No Delirium (n = 28) | Total (n = 75) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE, points, mean (SD) | 7.6 (2.4) | 8.4 (2.2) | 7.9 (2.3) | 0.23 * |

| CAM positive, n (%) | 47 (100) | 4 (14.3) | 51 (68.0) | <0.001 † |

| MDAS, points, mean (SD) | 16.63 (3.71) | 14.8 (4.5) | 15.9 (4.1) | 0.22 * |

| MDAS ≥ 13 points, n (%) | 40 (85.1) | 21 (75.0) | 61 (81.3) | 0.19 † |

| Severity of Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDAS Items | None = 0 | Mild = 1 | Moderate = 2 | Severe = 3 | Mean (SD) |

| Awareness | 10 (13.5) | 7 (9.2) | 43 (58.1) | 14 (18.9) | 1.82 (0.89) |

| Disorientation | 3 (4.1) | 19 (25.7) | 41 (55.4) | 11 (14.9) | 1.84 (0.73) |

| Memory | 19 (25.7) | 8 (10.8) | 33 (44.6) | 14 (18.9) | 1.57 (1.07) |

| Digit span | 33 (44.6) | 9 (12.2) | 21 (28.9) | 11 (14.9) | 1.14 (1.15) |

| Attention | 5 (8.1) | 14 (18.9) | 38 (51.4) | 16 (21.6) | 1.86 (0.85) |

| Disorganized thinking | 7 (9.5) | 13 (17.6) | 39 (52.7) | 15 (20.3) | 1.84 (0.86) |

| Perception | 24 (32.4) | 7 (9.5) | 32 (43.2) | 11 (14.9) | 1.41 (1.09) |

| Delusions | 31 (41.9) | 6 (8.1) | 27 (36.5) | 10 (13.5) | 1.22 (1.14) |

| Psychomotor activity | 26 (35.1) | 8 (10.8) | 28 (37.8) | 12 (16.2) | 1.35 (1.13) |

| Sleep–wake cycle | 8 (10.8) | 1 (1.4) | 54 (73) | 11 (14.9) | 1.92 (0.77) |

| Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

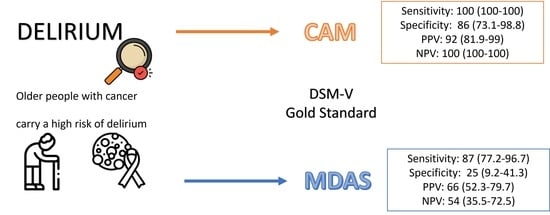

| MDAS ≥ 13 (gold DSM) | 87 (77.2–96.7) | 25 (9.2–41.3) | 66 (52.3–79.7) | 54 (35.5–72.5) |

| CAM (gold DSM) | 100 (100–100) | 86 (73.1–98.8) | 92 (81.9–99) | 100 (100–100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llisterri-Sánchez, P.; Benlloch, M.; Pérez-Ros, P. The Confusion Assessment Method Could Be More Accurate than the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale for Diagnosing Delirium in Older Cancer Patients: An Exploratory Study. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8245-8254. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090598

Llisterri-Sánchez P, Benlloch M, Pérez-Ros P. The Confusion Assessment Method Could Be More Accurate than the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale for Diagnosing Delirium in Older Cancer Patients: An Exploratory Study. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(9):8245-8254. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090598

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlisterri-Sánchez, Paula, María Benlloch, and Pilar Pérez-Ros. 2023. "The Confusion Assessment Method Could Be More Accurate than the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale for Diagnosing Delirium in Older Cancer Patients: An Exploratory Study" Current Oncology 30, no. 9: 8245-8254. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090598