Investigation of Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer and Structural Dynamics in Bis-Benzimidazole Derivative (BBM)

Abstract

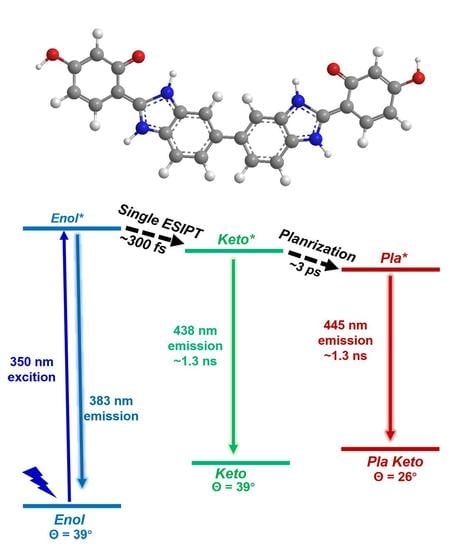

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Steady-State Absorption and Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.2. Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

2.3. Femtosecond Fluorescence Upconversion Spectroscopy

2.4. Femtosecond Raman Stimulated Spectroscopy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of BBM

3.2. Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

3.3. Time-Resolved Upconversion Fluorescence Spectroscopy

3.4. Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy (FSRS)

3.5. Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henary, M.M.; Wu, Y.; Fahrni, C.J. Zinc(II)-selective ratiometric fluorescent sensors based on inhibition of excited-state intramolecular proton transfer. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Dou, B.; Wright, B.; Wang, J.; Pang, Y. Zn2+ binding-enabled excited state intramolecular proton transfer: A step toward new near-infrared fluorescent probes for imaging applications. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2012, 1, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.E.; Lee, S.; You, Y.; Baek, K.H.; Ohkubo, K.; Cho, J.; Fukuzumi, S.; Shin, I.; Park, S.Y.; Nam, W. Fluorescent zinc sensor with minimized proton-induced interferences: Photophysical mechanism for fluorescence turn-on response and detection of endogenous free zinc ions. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 8760–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akutsu, K.; Mori, S.; Shinmei, K.; Iwase, H.; Nakano, Y.; Fujii, Y. Investigation of substitution effect on fluorescence properties of Zn2+ elective ratiometric fluorescent compounds: 2-(2’-Hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole derivatives. Talanta 2016, 146, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, R.; Sikdar, Y.; Sahu, S.; Das Mukhopadhyay, C.; Drew, M.G.B.; Goswami, S. Benzimidazole based ESIPT active chemosensors enable nano–molar detection of Cu2+ in 90% aqueous solution, MCF–7 cells, and plants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2022, 431, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbatti, M.; Aquino, A.J.; Lischka, H.; Schriever, C.; Lochbrunner, S.; Riedle, E. Ultrafast internal conversion pathway and mechanism in 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole: A case study for excited-state intramolecular proton transfer systems. PCCP 2009, 11, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vivie-Riedle, R.; De Waele, V.; Kurtz, L.; Riedle, E. Ultrafast excited-state proton transfer of 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole: Theoretical analysis of the skeletal deformations and the active vibrational modes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 10591–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbrunner, S.; Wurzer, A.J.; Riedle, E. Ultrafast excited-state proton transfer and subsequent coherent skeletal motion of 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 10699–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, S.M.; Usman, A.; AlZayer, M.; Hamdi, G.A.; Alarousu, E.; Mohammed, O.F. Solvent-dependent excited-state hydrogen transfer and intersystem crossing in 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)-benzothiazole. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 2596–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Abou-Zied, O.K.; Yu, C.; Romesberg, F.E.; Glasbeek, M. Femtosecond fluorescence upconversion studies of excited-state proton-transfer dynamics in 2-(2‘-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole (HBO) in liquid solution and DNA. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 367, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Park, J.; Seo, J.; Park, S.Y.; Joo, T. Excited State Intramolecular Proton Transfer and Charge Transfer Dynamics of a 2-(2‘-Hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole Derivative in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5618–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, S.R.; Rodriguez, M.C.R.; Mosquera, M.; Rodriguez-Prieto, F. Excited-state intramolecular proton transfer in 2-(3’-hydroxy-2’-pyridyl)benzoxazole. Evidence of coupled proton and charge transfer in the excited state of some o-hydroxyarylbenzazoles. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 1814–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, S.R.; Rodriguez, M.C.R.; Mosquera, M.; Rodriguez-Prieto, F. Rotamerism, tautomerism, and excited-state intramolecular proton transfer in 2-(4’-N,N-diethylamino-2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazoles: Novel benzimidazoles undergoing excited-state intramolecular coupled proton and charge transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W.; Laermer, F.; Elsaesser, T. Femtosecond Studies of Excited-State Proton and Deuterium Transfer in Benzothiazole Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 10391–10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, M.; Omidyan, R. Photochromism of 2-(2-Hydroxyphenyl) Benzothiazole (HBT) and Its Derivatives: A Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 3182–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijeau, S.; Foster, D.; Hohenstein, E.G. Excited-State Dynamics of 2-(2’-Hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole: Ultrafast Proton Transfer and Internal Conversion. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 4595–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, O.F.; Luber, S.; Batista, V.S.; Nibbering, E.T. Ultrafast branching of reaction pathways in 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole in polar acetonitrile solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 7550–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcos, N.; Gutierrez, M.; Liras, M.; Sanchez, F.; Douhal, A. An abnormally slow proton transfer reaction in a simple HBO derivative due to ultrafast intramolecular-charge transfer events. PCCP 2015, 17, 16257–16269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayal, S.; Roy, K.; Lakshmanna, Y.A.; Umapathy, S. Probing the effect of solvation on photoexcited 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole via ultrafast Raman loss spectroscopic studies. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 044310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wu, Y.; Pu, R.; Shi, L.; Jiang, J.; Du, J.; Guo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W. Tracking Ultrafast Structural Dynamics in a Dual-Emission Anti-Kasha-Active Fluorophore Using Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 4466–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wei, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, J.; Liu, H.; Du, J.; Weng, T.-C.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Huang, Y.; et al. Tracking Ultrafast Fluorescence Switch-On and Color-Tuned Dynamics in Acceptor–Donor–Acceptor Chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 10796–10804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, G.; Kong, J.; Niu, X.; Chan, J.M.W.; Liu, W.; Xia, A. Direct Tracking Excited-State Intramolecular Charge Redistribution of Acceptor-Donor-Acceptor Molecule by Means of Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 4456–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Han, F.; Smith, C.; Fang, C. Ultrafast conformational dynamics of pyranine during excited state proton transfer in aqueous solution revealed by femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 10535–10550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Tang, L.; Oscar, B.G.; Chen, C. Capturing Structural Snapshots during Photochemical Reactions with Ultrafast Raman Spectroscopy: From Materials Transformation to Biosensor Responses. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 3253–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Tang, L.; Oscar, B.G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Fang, C. Tracking Ultrafast Vibrational Cooling during Excited-State Proton Transfer Reaction with Anti-Stokes and Stokes Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Han, S.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Y.; Chang, L.Y.; Pao, C.W.; Chen, J.L.; Chen, J.M.; Haw, S.C. A bis-benzimidazole PMO ratiometric fluorescence sensor exhibiting AIEE and ESIPT for sensitive detection of Cu2+. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13567–13575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfe, G.J.; Melzig, M.; Schneider, S.; Dörr, F. The role of tautomeric and rotameric species in the photophysics of 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole. Chem. Phys. 1983, 77, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Zied, O.K.; Jimenez, R.; Thompson, E.H.Z.; Millar, D.P.; Romesberg, F.E. Solvent-Dependent Photoinduced Tautomerization of 2-(2’-Hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 3665–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.T.; Studer, S.L.; Martinez, M.L. Studies of the Triplet-State of 2-(2’-Hydroxyphenyl)Benzothiazole. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1991, 178, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, A.; Momotake, A.; Nagahata, R.; Arai, T. Enhancement of the large Stokes-shifted fluorescence emission from the 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole core in a dendrimer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 9731–9736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, M.L.; Gardecki, J.A.; Maroncelli, M. Rotational dynamics of coumarin 153: Time-dependent friction, dielectric friction, and other nonhydrodynamic effects. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 1030–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, M.L.; Gardecki, J.A.; Papazyan, A.; Maroncelli, M. Subpicosecond Measurements of Polar Solvation Dynamics—Coumarin-153 Revisited. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 17311–17337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, M.; Rettig, W.; Bonafoux, D.; Lapouyade, R. Photoinduced intramolecular charge transfer in a series of differently twisted donor—Acceptor biphenyls as revealed by fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 3388–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, C.L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.A.; Chao, W.C.; Su, J.; Tian, H.; Chou, P.T. Snapshotting the Excited-State Planarization of Chemically Locked N,N’-Disubstituted Dihydrodibenzo[a,c]phenazines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.G.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.H.; Chen, Y.A.; Chen, M.C.; Lin, J.A.; Huang, C.Y.; Su, J.; Tian, H.; Chou, P.T. Phenothiazine Scope: Steric Strain Induced Planarization and Excimer Formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13297–13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Abeywickrama, C.S.; Huo, D.; Kong, J.; Tao, M.; Xia, A.; Pang, Y.; Wan, Y. Solvation Controlled Excited-State Planarization in a Push–Pull Pyrene Dye. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 8550–8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Frontiera, R.R.; Tran, R.; Mathies, R.A. Mapping GFP structure evolution during proton transfer with femtosecond Raman spectroscopy. Nature 2009, 462, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.M.; Wang, Y.L.; Tang, L.T.; Oscar, B.G.; Zhu, L.D.; Fang, C. Panoramic portrait of primary molecular events preceding excited state proton transfer in water. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 5484–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miertuš, S.; Scrocco, E.; Tomasi, C.J. Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilizaion of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem. Phys. 1981, 55, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miertuš, S.; Tomasi, J. Approximate evaluations of the electrostatic free energy and internal energy changes in solution processes. Chem. Phys. 1982, 65, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becke, A.D. Perspective on “Density functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange”. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-ahuir, J.L.; Silla, E.; Tuñon, I. GEPOL: An improved description of molecular surfaces. III. A new algorithm for the computation of a solvent-excluding surface. J. Comput. Chem. 1994, 15, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. Gaussian 09, Revision d. 01; Gaussian. Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, J.; Weng, T.-C.; Ren, Y.; Han, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W. Investigation of Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer and Structural Dynamics in Bis-Benzimidazole Derivative (BBM). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119438

Xie J, Wang Z, Zhu R, Jiang J, Weng T-C, Ren Y, Han S, Huang Y, Liu W. Investigation of Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer and Structural Dynamics in Bis-Benzimidazole Derivative (BBM). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(11):9438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119438

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Junhan, Ziyu Wang, Ruixue Zhu, Jiaming Jiang, Tsu-Chien Weng, Yi Ren, Shuhua Han, Yifan Huang, and Weimin Liu. 2023. "Investigation of Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer and Structural Dynamics in Bis-Benzimidazole Derivative (BBM)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 11: 9438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119438