Ephs and Ephrins in Adult Endothelial Biology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Ephrins and Ephs Basic Structure and Signaling

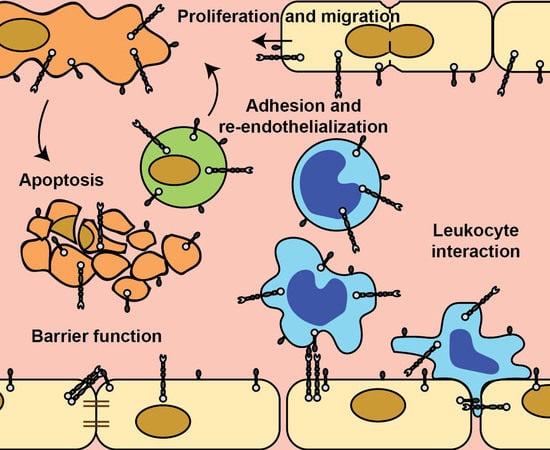

2.1. Ephrins and Ephs Basic Structure

2.2. Forward Signaling

2.3. Reverse Signaling

2.4. Alternative Signaling

3. Ephrin and Eph Expression in Endothelial Cells

3.1. Ephrins and Ephs Expressed under Homeostasis

3.2. Ephrin and Eph Regulation by Inflammation and Hemodynamic Factors

3.3. Ephrin and Eph Regulation by Other Environmental Conditions

3.4. Ephrin and Eph Regulation by MicroRNA’s

4. Ephrins and Ephs in Endothelial Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis

4.1. Ephrins and Ephs in Endothelial Cell Proliferation

4.2. Ephrins and Ephs in Endothelial Cell Apoptosis

5. Ephrins and Ephs in Endothelial Cell Adhesion, Spreading and Migration

5.1. EphrinA Family Members in Endothelial Cell Migration

5.2. EphrinB Family Members on Endothelial Cell Adhesion and Spreading

5.3. EphrinB Forward Signaling on Endothelial Migration

5.4. EphrinB Reverse Signaling on Endothelial Migration

6. Ephrins and Ephs in Endothelial Barrier Function

6.1. EphA2 Forward Signaling Induces Vascular Leakage

6.2. EphrinB/EphB Signaling in Vascular Leakage

7. Ephrins and Ephs in Leukocyte-Endothelial Cell Interactions

7.1. EphrinA/EphA-Mediated Leukocyte Adhesion and Migration

7.2. EphrinB/Eph-Mediated Leukocyte Adhesion and Migration

8. Ephrins and Ephs and Disease

8.1. Vascular Leakage and Ischemia Reperfusion Damage

8.2. Atherosclerosis

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CCL | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand |

| CXCL | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand |

| EPC | Endothelial progenitor cell |

| Eph | Erythropoietin-producing human hepatocellular receptor |

| Ephrin | Eph family receptor interacting protein |

| ERK1 | MAPK3 |

| ERK2 | MAPK1 |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| GPI | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol |

| HAEC | Human aortic endothelial cell |

| HCAEC | Human coronary artery endothelial cell |

| HDMEC | Human dermal microvascular endothelial cell |

| HLMVEC | Human lung microvascular endothelial cell |

| HUVEC | Human umbilical vein endothelial cell |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| MAPK | Mitogen activated protein kinase |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NFAT | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOS3 | Nitric oxide synthase 3 |

| PAR-1 | Protease-activated receptor 1 |

| PDZ | PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| RET | Rearranged during transfection |

| RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase |

| SAM | Sterile alpha motif |

| SH2 | Src Homology 2 |

| SFK | Src family kinase |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin receptor kinase B |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion protein 1 |

| VE-cadherin | Vascular endothelial cadherin |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR | VEGF receptor |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens 1 |

References

- Hirai, H.; Maru, Y.; Hagiwara, K.; Nishida, J.; Takaku, F. A novel putative tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the eph gene. Science 1987, 238, 1717–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kania, A.; Klein, R. Mechanisms of Ephrin-Eph Signalling in Development, Physiology and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.U.; Chen, Z.-F.; Anderson, D.J. Molecular Distinction and Angiogenic Interaction between Embryonic Arteries and Veins Revealed by ephrin-B2 and Its Receptor Eph-B4. Cell 1998, 93, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerety, S.S.; Wang, H.U.; Chen, Z.F.; Anderson, D.J. Symmetrical mutant phenotypes of the receptor EphB4 and its specific transmembrane ligand ephrin-B2 in cardiovascular development. Mol. Cell 1999, 4, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, T.K.; Lamb, T.J. Emerging Roles for Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands in Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michiels, C. Endothelial cell functions. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 196, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullander, K.; Klein, R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisabeth, E.M.; Falivelli, G.; Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling and ephrins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salvucci, O.; Tosato, G. Essential roles of EphB receptors and EphrinB ligands in endothelial cell function and angiogenesis. Adv. Cancer Res. 2012, 114, 21–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, N.J.; Henkemeyer, M. Ephrin reverse signaling in axon guidance and synaptogenesis. SEMIN Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 23, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph-Ephrin Bidirectional Signaling in Physiology and Disease. Cell 2008, 133, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Funk, S.D.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Albert, P.; Traylor, J.G., Jr.; Jin, L.; Chen, J.; Orr, A.W. EphA2 activation promotes the endothelial cell inflammatory response: A potential role in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wiedemann, E.; Jellinghaus, S.; Ende, G.; Augstein, A.; Sczech, R.; Wielockx, B.; Weinert, S.; Strasser, R.H.; Poitz, D.M. Regulation of endothelial migration and proliferation by ephrin-A1. Cell. Signal. 2017, 29, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Peng, W.; Gao, Z.; Ouyang, H.; Yan, T.; Ding, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, B.; Mao, L.; et al. Activation of EphA4 induced by EphrinA1 exacerbates disruption of the blood-brain barrier following cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via the Rho/ROCK signaling pathway. Exp. Med. 2018, 16, 2651–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohura, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Ichioka, S.; Sokabe, T.; Nakatsuka, H.; Baba, A.; Shibata, M.; Nakatsuka, T.; Harii, K.; Wada, Y.; et al. Global analysis of shear stress-responsive genes in vascular endothelial cells. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2003, 10, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fasanaro, P.; D’Alessandra, Y.; Di Stefano, V.; Melchionna, R.; Romani, S.; Pompilio, G.; Capogrossi, M.C.; Martelli, F. MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 15878–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, F.; Qiu, H.; Zhou, L.; Shen, X.; Yang, L.; Ding, K. WSS25 inhibits Dicer, downregulating microRNA-210, which targets Ephrin-A3, to suppress human microvascular endothelial cell (HMEC-1) tube formation. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X.; Bihl, J.C.; Yang, Y. NPC-EXs Alleviate Endothelial Oxidative Stress and Dysfunction through the miR-210 Downstream Nox2 and VEGFR2 Pathways. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 9397631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Devraj, K.; Moller, K.; Liebner, S.; Hecker, M.; Korff, T. EphrinB-mediated reverse signalling controls junctional integrity and pro-inflammatory differentiation of endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 112, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korff, T.; Dandekar, G.; Pfaff, D.; Fuller, T.; Goettsch, W.; Morawietz, H.; Schaffner, F.; Augustin, H.G. Endothelial ephrinB2 is controlled by microenvironmental determinants and associates context-dependently with CD31. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Gils, J.M.; Ramkhelawon, B.; Fernandes, L.; Stewart, M.C.; Guo, L.; Seibert, T.; Menezes, G.B.; Cara, D.C.; Chow, C.; Kinane, T.B.; et al. Endothelial expression of guidance cues in vessel wall homeostasis dysregulation under proatherosclerotic conditions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korff, T.; Braun, J.; Pfaff, D.; Augustin, H.G.; Hecker, M. Role of ephrinB2 expression in endothelial cells during arteriogenesis: Impact on smooth muscle cell migration and monocyte recruitment. Blood 2008, 112, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Masumura, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Shimizu, N.; Obi, S.; Ando, J. Shear stress increases expression of the arterial endothelial marker ephrinB2 in murine ES cells via the VEGF-Notch signaling pathways. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Model, L.S.; Hall, M.R.; Wong, D.J.; Muto, A.; Kondo, Y.; Ziegler, K.R.; Feigel, A.; Quint, C.; Niklason, L.; Dardik, A. Arterial shear stress reduces eph-b4 expression in adult human veins. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2014, 87, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Ando, J.; Matsumoto, K.; Matsuda, T. Arterial shear stress augments the differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells adhered to VEGF-bound surfaces. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 423, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettsch, W.; Augustin, H.G.; Morawietz, H. Down-regulation of endothelial ephrinB2 expression by laminar shear stress. Endothel. J. Endothel. Cell Res. 2004, 11, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, L.; Zhang, H.; Hachy, S.; Satohisa, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Parast, M.; Zheng, J.; Chen, D.B. Preeclampsia up-regulates angiogenesis-associated microRNA (i.e., miR-17, -20a, and -20b) that target ephrin-B2 and EPHB4 in human placenta. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E1051–E1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Good, R.J.; Hernandez-Lagunas, L.; Allawzi, A.; Maltzahn, J.K.; Vohwinkel, C.U.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Kompella, U.; Birukov, K.G.; Carpenter, T.C.; Sucharov, C.C.; et al. MicroRNA Dysregulation in Lung Injury: The Role of the miR-26a/EphA2 Axis in Regulation of Endothelial Permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Heng, X.; Yu, J.; Su, Q.; Guan, X.; You, C.; Wang, L.; Che, F. miR-137 regulates the migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by targeting ephrin-type A receptor 7. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 1475–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, M.H.; Chan, L.S.; Kwok, H.H.; Wong, R.N.; Yue, P.Y. Role of microRNA-520h in 20(R)-ginsenoside-Rg3-mediated angiosuppression. J. Ginseng Res. 2016, 40, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zamora, D.O.; Babra, B.; Pan, Y.; Planck, S.R.; Rosenbaum, J.T. Human leukocytes express ephrinB2 which activates microvascular endothelial cells. Cell. Immunol. 2006, 242, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, N.W.; Baluk, P.; Pan, L.; Kwan, M.; Holash, J.; DeChiara, T.M.; McDonald, D.M.; Yancopoulos, G.D. Ephrin-B2 selectively marks arterial vessels and neovascularization sites in the adult, with expression in both endothelial and smooth-muscle cells. Dev. Biol. 2001, 230, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shin, D.; Garcia-Cardena, G.; Hayashi, S.-I.; Gerety, S.; Asahara, T.; Stavrakis, G.; Isner, J.; Folkman, J.; Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; Anderson, D.J. Expression of ephrinB2 identifies a stable genetic difference between arterial and venous vascular smooth muscle as well as endothelial cells, and marks subsets of microvessels at sites of adult neovascularization. Dev. Biol. 2001, 230, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salvucci, O.; de la Luz Sierra, M.; Martina, J.A.; McCormick, P.J.; Tosato, G. EphB2 and EphB4 receptors forward signaling promotes SDF-1-induced endothelial cell chemotaxis and branching remodeling. Blood 2006, 108, 2914–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakamoto, A.; Sugamoto, Y.; Tokunaga, Y.; Yoshimuta, T.; Hayashi, K.; Konno, T.; Kawashiri, M.A.; Takeda, Y.; Yamagishi, M. Expression profiling of the ephrin (EFN) and Eph receptor (EPH) family of genes in atherosclerosis-related human cells. J. Int. Med. Res. 2011, 39, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Zagoura, D.; Keck, C.; Pietrowski, D. Expression of Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their ligands in human Granulosa lutein cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Off. J. Ger. Soc. Endocrinol. Ger. Diabetes Assoc. 2006, 114, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J.; Schomberg, S.; Schroeder, W.; Carpenter, T.C. Endothelial EphA receptor stimulation increases lung vascular permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008, 295, L431–L439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Dong, Y.; Fang, W.; Shang, D.; Liu, D.; Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.H. VEGF increases paracellular permeability in brain endothelial cells via upregulation of EphA2. Anat. Rec. 2014, 297, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T.C.; Schroeder, W.; Stenmark, K.R.; Schmidt, E.P. Eph-A2 Promotes Permeability and Inflammatory Responses to Bleomycin-Induced Lung Injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Hernando, C.; Suárez, Y. MicroRNAs in endothelial cell homeostasis and vascular disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2018, 25, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Z.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Q. The role of microvesicles containing microRNAs in vascular endothelial dysfunction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7933–7945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santulli, G. MicroRNAs and Endothelial (Dys) Function. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 1638–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Zonneveld, A.-J.; Rabelink, T.J. Endothelial progenitor cells: Biology and therapeutic potential in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2006, 15, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brantley-Sieders, D.M.; Caughron, J.; Hicks, D.; Pozzi, A.; Ruiz, J.C.; Chen, J. EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase regulates endothelial cell migration and vascular assembly through phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated Rac1 GTPase activation. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinle, J.J.; Meininger, C.J.; Forough, R.; Wu, G.; Wu, M.H.; Granger, H.J. Eph B4 receptor signaling mediates endothelial cell migration and proliferation via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 43830–43835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, L.C.; Wang, X.Q.; Lu, K.; Deng, X.L.; Zhang, C.W.; Luo, H.; Xu, X.D.; Chen, X.M.; Yan, L.; Wang, Y.Q.; et al. Ephrin-B2/Fc promotes proliferation and migration, and suppresses apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41348–41363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sturz, A.; Bader, B.; Thierauch, K.H.; Glienke, J. EphB4 signaling is capable of mediating ephrinB2-induced inhibition of cell migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 313, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Oike, Y.; Ito, Y.; Maekawa, H.; Miyata, K.; Shimomura, T.; Suda, T. Distinct roles of ephrin-B2 forward and EphB4 reverse signaling in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jadlowiec, C.C.; Feigel, A.; Yang, C.; Feinstein, A.J.; Kim, S.T.; Collins, M.J.; Kondo, Y.; Muto, A.; Dardik, A. Reduced adult endothelial cell EphB4 function promotes venous remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C627–C635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zuo, K.; Zhi, K.; Zhang, X.; Lu, C.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; He, B. A dysregulated microRNA-26a/EphA2 axis impairs endothelial progenitor cell function via the p38 MAPK/VEGF pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 35, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foubert, P.; Silvestre, J.S.; Souttou, B.; Barateau, V.; Martin, C.; Ebrahimian, T.G.; Lere-Dean, C.; Contreres, J.O.; Sulpice, E.; Levy, B.I.; et al. PSGL-1-mediated activation of EphB4 increases the proangiogenic potential of endothelial progenitor cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Foubert, P.; Squiban, C.; Holler, V.; Buard, V.; Dean, C.; Levy, B.I.; Benderitter, M.; Silvestre, J.S.; Tobelem, G.; Tamarat, R. Strategies to Enhance the Efficiency of Endothelial Progenitor Cell Therapy by Ephrin B2 Pretreatment and Coadministration with Smooth Muscle Progenitor Cells on Vascular Function During the Wound-Healing Process in Irradiated or Nonirradiated Condition. Cell Transplant. 2015, 24, 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Luo, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, W.; Luo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, L. NOTCH4 signaling controls EFNB2-induced endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction in preeclampsia. Reproduction 2016, 152, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Luo, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zou, L. The role of Delta-like 4 ligand/Notch-ephrin-B2 cascade in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia by regulating functions of endothelial progenitor cell. Placenta 2015, 36, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis-Nascimento, P.; Tsenkina, Y.; Liebl, D.J. EphB3 signaling induces cortical endothelial cell death and disrupts the blood-brain barrier after traumatic brain injury. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J.; Im, H.; Cao, A.; Hennigs, J.K.; Wang, L.; Sa, S.; Chen, P.-I.; Nickel, N.P.; Miyagawa, K.; Hopper, R.K.; et al. RNA Sequencing Analysis Detection of a Novel Pathway of Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huynh-Do, U.; Stein, E.; Lane, A.A.; Liu, H.; Cerretti, D.P.; Daniel, T.O. Surface densities of ephrin-B1 determine EphB1-coupled activation of cell attachment through alphavbeta3 and alpha5beta1 integrins. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2165–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, E.; Lane, A.A.; Cerretti, D.P.; Schoecklmann, H.O.; Schroff, A.D.; Van Etten, R.L.; Daniel, T.O. Eph receptors discriminate specific ligand oligomers to determine alternative signaling complexes, attachment, and assembly responses. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, T.; Korff, T.; Kilian, A.; Dandekar, G.; Augustin, H.G. Forward EphB4 signaling in endothelial cells controls cellular repulsion and segregation from ephrinB2 positive cells. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groeger, G.; Nobes, C.D. Co-operative Cdc42 and Rho signalling mediates ephrinB-triggered endothelial cell retraction. Biochem. J. 2007, 404, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huynh-Do, U.; Vindis, C.; Liu, H.; Cerretti, D.P.; McGrew, J.T.; Enriquez, M.; Chen, J.; Daniel, T.O. Ephrin-B1 transduces signals to activate integrin-mediated migration, attachment and angiogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 3073–3081. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Wang, P.; Zhu, S.; Zou, T.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Heng, B.C.; Diogenes, A.; Zhang, C. EphrinB2 Stabilizes Vascularlike Structures Generated by Endothelial Cells and Stem Cells from Apical Papilla. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, K.; Endo, A.; Ogita, H.; Kawana, A.; Yamagishi, A.; Kitabatake, A.; Matsuda, M.; Mochizuki, N. Adaptor protein Crk is required for ephrin-B1-induced membrane ruffling and focal complex assembly of human aortic endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 4231–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bruhl, T.; Urbich, C.; Aicher, D.; Acker-Palmer, A.; Zeiher, A.M.; Dimmeler, S. Homeobox A9 transcriptionally regulates the EphB4 receptor to modulate endothelial cell migration and tube formation. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walshe, J.; Richardson, N.A.; Al Abdulsalam, N.K.; Stephenson, S.A.; Harkin, D.G. A potential role for Eph receptor signalling during migration of corneal endothelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 170, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, C.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Shi, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, L.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. Bidirectional juxtacrine ephrinB2/Ephs signaling promotes angiogenesis of ECs and maintains self-renewal of MSCs. Biomaterials 2018, 172, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maekawa, H.; Oike, Y.; Kanda, S.; Ito, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Kurihara, H.; Nagai, R.; Suda, T. Ephrin-B2 induces migration of endothelial cells through the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase pathway and promotes angiogenesis in adult vasculature. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bochenek, M.L.; Dickinson, S.; Astin, J.W.; Adams, R.H.; Nobes, C.D. Ephrin-B2 regulates endothelial cell morphology and motility independently of Eph-receptor binding. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kida, Y.; Ieronimakis, N.; Schrimpf, C.; Reyes, M.; Duffield, J.S. EphrinB2 reverse signaling protects against capillary rarefaction and fibrosis after kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Jasn 2013, 24, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salvucci, O.; Maric, D.; Economopoulou, M.; Sakakibara, S.; Merlin, S.; Follenzi, A.; Tosato, G. EphrinB reverse signaling contributes to endothelial and mural cell assembly into vascular structures. Blood 2009, 114, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brantley-Sieders, D.M.; Chen, J. Eph receptor tyrosine kinases in angiogenesis: From development to disease. Angiogenesis 2004, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavard, J.; Gutkind, J.S. VEGF controls endothelial-cell permeability by promoting the beta-arrestin-dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, T.K.; Mimche, P.N.; Bray, C.; Umaru, B.; Brady, L.M.; Stone, C.; Eboumbou Moukoko, C.E.; Lane, T.E.; Ayong, L.S.; Lamb, T.J. EphA2 contributes to disruption of the blood-brain barrier in cerebral malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woodruff, T.M.; Wu, M.C.; Morgan, M.; Bain, N.T.; Jeanes, A.; Lipman, J.; Ting, M.J.; Boyd, A.W.; Taylor, S.M.; Coulthard, M.G. Epha4-Fc Treatment Reduces Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Intestinal Injury by Inhibiting Vascular Permeability. SHOCK 2016, 45, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, D.; Heroult, M.; Riedel, M.; Reiss, Y.; Kirmse, R.; Ludwig, T.; Korff, T.; Hecker, M.; Augustin, H.G. Involvement of endothelial ephrin-B2 in adhesion and transmigration of EphB-receptor-expressing monocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 3842–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tobia, C.; Chiodelli, P.; Nicoli, S.; Dell’era, P.; Buraschi, S.; Mitola, S.; Foglia, E.; van Loenen, P.B.; Alewijnse, A.E.; Presta, M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 controls venous endothelial barrier integrity in zebrafish. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, e104–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luxan, G.; Stewen, J.; Diaz, N.; Kato, K.; Maney, S.K.; Aravamudhan, A.; Berkenfeld, F.; Nagelmann, N.; Drexler, H.C.; Zeuschner, D.; et al. Endothelial EphB4 maintains vascular integrity and transport function in adult heart. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruppathi, C.; Regmi, S.C.; Wang, D.-M.; Mo, G.C.H.; Toth, P.T.; Vogel, S.M.; Stan, R.V.; Henkemeyer, M.; Minshall, R.D.; Rehman, J.; et al. EphB1 interaction with caveolin-1 in endothelial cells modulates caveolae biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeken, D.; Bruikman, C.; Cox, S.; Zhang, H.; Lalai, R.; Koudijs, A.; Zonneveld, A.; Hovingh, G.; Gils, J. EPH receptor B2 stimulates human monocyte adhesion and migration independently of its EphrinB ligands. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharfe, N.; Nikolic, M.; Cimpeon, L.; Van De Kratts, A.; Freywald, A.; Roifman, C.M. EphA and ephrin-A proteins regulate integrin-mediated T lymphocyte interactions. Mol. Immunol. 2008, 45, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharfe, N.; Freywald, A.; Toro, A.; Dadi, H.; Roifman, C. Ephrin stimulation modulates T cell chemotaxis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002, 32, 3745–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasheim, H.C.; Delabie, J.; Finne, E.F. Ephrin-A1 binding to CD4+ T lymphocytes stimulates migration and induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK2. Blood 2005, 105, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ende, G.; Poitz, D.M.; Wiedemann, E.; Augstein, A.; Friedrichs, J.; Giebe, S.; Weinert, S.; Werner, C.; Strasser, R.H.; Jellinghaus, S. TNF-alpha-mediated adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells-The role of ephrinA1. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 77, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinghaus, S.; Poitz, D.M.; Ende, G.; Augstein, A.; Weinert, S.; Stutz, B.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C.; Pasquale, E.B.; Strasser, R.H. Ephrin-A1/EphA4-mediated adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 2201–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finney, A.C.; Funk, S.D.; Green, J.; Yurdagul, A.; Rana, M.A.; Pistorius, R.; Henry, M.; Yurochko, A.D.; Pattillo, C.B.; Traylor, J.G.; et al. EphA2 Expression Regulates Inflammation and Fibroproliferative Remodeling in Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, S.D.; Finney, A.C.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Pattillo, C.B.; Orr, A.W. EphA2 stimulates VCAM-1 expression through calcium-dependent NFAT1 activity. Cell. Signal. 2018, 49, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.; Sukhatme, V.P. Receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 mediates thrombin-induced upregulation of ICAM-1 in endothelial cells in vitro. Thromb. Res. 2009, 123, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, J.; Hoffmann, S.C.; Feldner, A.; Ludwig, T.; Henning, R.; Hecker, M.; Korff, T. Endothelial cell ephrinB2-dependent activation of monocytes in arteriosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakamoto, A.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Sugamoto, Y.; Higashikata, T.; Miyamoto, S.; Kawashiri, M.A.; Yagi, K.; Konno, T.; Hayashi, K.; Fujino, N.; et al. Expression and function of ephrin-B1 and its cognate receptor EphB2 in human atherosclerosis: From an aspect of chemotaxis. Clin. Sci. 2008, 114, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kitamura, T.; Kabuyama, Y.; Kamataki, A.; Homma, M.K.; Kobayashi, H.; Aota, S.; Kikuchi, S.-i.; Homma, Y. Enhancement of lymphocyte migration and cytokine production by ephrinB1 system in rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, C189–C196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, H.; Broux, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Ghannam, S.; Jin, W.; Larochelle, C.; Prat, A.; Wu, J. EphrinB1 and EphrinB2 regulate T cell chemotaxis and migration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 91, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poitz, D.M.; Ende, G.; Stutz, B.; Augstein, A.; Friedrichs, J.; Brunssen, C.; Werner, C.; Strasser, R.H.; Jellinghaus, S. EphrinB2/EphA4-mediated activation of endothelial cells increases monocyte adhesion. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 68, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquilla, A.; Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins: Therapeutic opportunities. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015, 55, 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cercone, M.A.; Schroeder, W.; Schomberg, S.; Carpenter, T.C. EphA2 receptor mediates increased vascular permeability in lung injury due to viral infection and hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009, 297, L856–L863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.H.; Shin, M.H.; Douglas, I.S.; Chung, K.S.; Song, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, E.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; Chang, J.; et al. Erythropoietin-Producing Hepatoma Receptor Tyrosine Kinase A2 Modulation Associates with Protective Effect of Prone Position in Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghori, A.; Freimann, F.B.; Nieminen-Kelhä, M.; Kremenetskaia, I.; Gertz, K.; Endres, M.; Vajkoczy, P. EphrinB2 Activation Enhances Vascular Repair Mechanisms and Reduces Brain Swelling After Mild Cerebral Ischemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vivo, V.; Zini, I.; Cantoni, A.M.; Grandi, A.; Tognolini, M.; Castelli, R.; Ballabeni, V.; Bertoni, S.; Barocelli, E. Protection by the EPH-EPHRIN System Against Mesenteric Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. SHOCK 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.L.; Bretschger, S.; Latib, N.; Bezouevski, M.; Guo, Y.; Pleskac, N.; Liang, C.P.; Barlow, C.; Dansky, H.; Breslow, J.L.; et al. Localization of atherosclerosis susceptibility loci to chromosomes 4 and 6 using the Ldlr knockout mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7946–7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Rao, S.; Shen, G.Q.; Li, L.; Moliterno, D.J.; Newby, L.K.; Rogers, W.J.; Cannata, R.; Zirzow, E.; Elston, R.C.; et al. Premature myocardial infarction novel susceptibility locus on chromosome 1P34-36 identified by genomewide linkage analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, X. EphA2 knockdown attenuates atherosclerotic lesion development in ApoE(-/-) mice. Cardiovasc. Pathol. Off. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2014, 23, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ephrin Ligands | Endothelial Cells | (Patho)physiological Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAECs | HAECs | HUVECs | HCAECs | HDMECs | HLMVECs | ||

| EphrinA1 | High | High | High | High | High | Increased by inflammation [12], increasing cell density [13], serum depletion [13], ischemia [14]. Decreased by shear stress [15]. | |

| EphrinA2 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | |||

| EphrinA3 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | Increased by hypoxia [16]. Decreased by miR-210 [16,17,18]. | ||

| EphrinA4 | High | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | |||

| EphrinA5 | High | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | |||

| EphrinB1 | High | Undetected | Moderate | Undetected | Increased by inflammation [19]. | ||

| EphrinB2 | High | High | High | High | Increased by inflammation [19,20,21], laminar or interrupted flow [22,23,24,25]. Unchanged by laminar flow [22]. Decreased by laminar flow [21,26], miR-20b [27]. | ||

| EphrinB3 | Moderate | Undetected | Moderate/no | Undetected | |||

| Eph Receptors | Endothelial Cells | (Patho)physiological Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAECs | HAECs | HUVECs | HCAECs | HDMECs | HLMVECs | ||

| EphA1 | Undetected | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | |||

| EphA2 | High | High | High | High | High | Increased by inflammation [12,20]. Decreased by miR-26a [28]. | |

| EphA3 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | |||

| EphA4 | High | High | Moderate | High | Increased by ischemia [14]. | ||

| EphA5 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | Moderate | ||

| EphA6 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | Moderate | ||

| EphA7 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | Decreased by miR-137 [29]. | ||

| EphA8 | Moderate | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | |||

| EphA10 | Low/no | Low/no | Low/no | ||||

| EphB1 | High | High | High | Moderate | |||

| EphB2 | High | High | High | Moderate | Decreased by miR-520h [30]. | ||

| EphB3 | Undetected | Moderate | High | Moderate | |||

| EphB4 | High | High | High | High | Decreased by inflammation [23], flow [23,24], miR-20b [27], miR-520h [30]. Unchanged by flow [31]. | ||

| EphB6 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vreeken, D.; Zhang, H.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; van Gils, J.M. Ephs and Ephrins in Adult Endothelial Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165623

Vreeken D, Zhang H, van Zonneveld AJ, van Gils JM. Ephs and Ephrins in Adult Endothelial Biology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(16):5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165623

Chicago/Turabian StyleVreeken, Dianne, Huayu Zhang, Anton Jan van Zonneveld, and Janine M. van Gils. 2020. "Ephs and Ephrins in Adult Endothelial Biology" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 16: 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165623