Teaching Is a Story Whose First Page Matters—Teacher Counselling as Part of Teacher Growth

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Finding the Essentials with the Help of Autoethnography and Discourse Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phase One—Key Factors in Constructing a Story

- Drawing up plans (term plans and course plans to support teaching);

- Operational culture, theory-in-use and classroom practices;

- Cognitive control, respecting one another, goal-oriented activity;

- Strengths and resources and how to utilise them;

- Resilience and how to strengthen it.

Supervisor A:From a work counselling perspective, would it not be rather bold to ask the students which questions they would like to address today? They might find topics for discussion from the webinar they have listened to, but if they had something else on their minds, we could give room for that as well. This would be a solution-focused approach that would help us tackle matters presented by the students in a timely manner.

Supervisor B:That is a bold suggestion, but it would also involve timeliness, the zone of proximal development and always scaffolding. It would enable the development of teacherhood in one’s own zone of proximal development and, at its best, make it possible to receive collegial support from others who are probably in a similar situation or who have already processed the situation.

Supervisor B:The uppermost feeling is enthusiasm towards the new model and the lately developed awareness of the importance of timely support. The new approach is also supported by my own experiences of the solution-focused approach and of the empowering nature of positive psychology in work counselling.

Supervisor A:There is also excitement in the air, caused by the following question: How will the students, who are used to completing assignments in accordance with a certain protocol, react to supervision that is based on each student’s current questions and objectives? Will the students be able to make good use of the supervision and really highlight their current supervision needs as regards their teacherhood? Will I be able to address questions that I have probably not been able to prepare for beforehand?

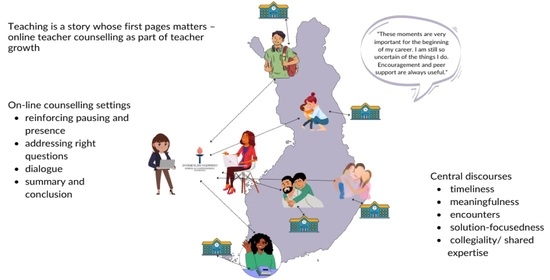

3.2. Phase Two—The Plot of the Story Is Composed by the Students

- Reinforcing pausing and presence;

- Addressing basic questions;

- Discussing the objectives;

- Summary and conclusion.

Supervisor B:I participated in the discussion a few times, but I do not think I gave any answers–we did not talk about plans at all, which is why it was easy to keep summaries and conclusions to a minimum.

Supervisor B:Old-fashioned practices and the lack of resources and materials was realism in the daily life of many students, so I instructed them to profoundly contemplate on their philosophy of education: What is possible even though you are lacking something? That started a good discussion about how easy it is to find reasons for not doing something and in a way sell one’s teacher hood. Instead, one could think about what one can do despite shortage of materials and how one could improve the resources and materials of the school step by step.

Supervisor B:The stories were touching and beautiful and conveyed the feeling that one’s work is meaningful: interaction, encounters, providing a sound basis for life, and producing shared memories were the common thread of being a teacher, and the examples of these were from daily life and meaningful encounters.

Supervisor A:Today we discussed broadly about what kind of a teacher one would like to be and what is meaningful in one’s teacherhood. Quite a many students considered that meaningful encounters are important. I noticed that it was not easy to verbalize this: How do meaningful encounters show in my daily life? Many said great things about encounters but were not able to give concrete examples. We discussed this for a long time. The students were perplexed, too, about how difficult it was to verbalize one’s actions even though that is one of the core tasks of a teacher.

Supervisor B:The assignment of the day–expressing one’s way of being a teacher in words–made everyone focus on the same issue in an atmosphere that was clearly meaningful. The students verbalized their thoughts very profoundly, and the respectful way they spoke about pupils and encounters with parents made me feel that it was a group of experts, not a group of students working on an assignment.

Supervisor A:I am happy that the students are so open when discussing “the burning issues of the day”: They are open about their uncertainties and situations that they have managed well. It is great that the students support one another and help each other to analyse their thoughts.

Supervisor B:Professional attitude and appreciation of one’s work were palpable when the students discussed current school-related questions, and we paused for a moment to consider authenticity as initiator of motivation. This had a firm basis on correspondence between the pupils of three students and the pupils’ enthusiasm about it.

Supervisor A:I sense that the students are looking forward to our meetings and are well-prepared for them. Some sit on the sofa with a cup of coffee, some have a pen and a notepad, some have a list of questions they wish to address together with their colleagues. The students have also started to talk about ‘work counselling’ instead of ‘practice supervision’.

Supervisor B:This time the discussion was lively and spontaneous, and I heard the phrase “I will use that in my class” several times. The students also openly gave one another feedback and praise when they felt good about what somebody said or felt it was thought-provoking.

3.3. Phase Three—Various Interpretations of the Story Form a Shared Experience

4. Discourses and Their Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Student feedback:I feel that during this practice period I have been safely seen off at working life. It has been really wonderful to assemble with my fellow students once more to discuss the challenges of working life. It was also comforting to notice that I am not alone with my anxiety, and that many things are actually fine. The webinars and other assignments were also good and supported my work. Thank you for seeing me off.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bullough, R.V.; Pinnegar, S. Guidelines for Quality in Autobiographical Forms of Self-Study Research. Educ. Res. 2001, 30, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kincheloe, J.L.; McLaren, P.; Steinberg, S.R. Critical pedagogy and qualitative research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Anneli, P. Asiakas Sosiaalityön Subjektina. In Asiakkuus Sosiaalityössä; Laitinen, M., Pohjola, A., Eds.; Gaudeamus Helsinki University Press: Helsinki, Finland, 2010; pp. 19–74. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, T.E.; Ellis, C.; Jones, S.H. Autoethnography. Int. Encycl. Commun. Res. Methods 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapadat, J.C. Ethics in Autoethnography and Collaborative Autoethnography. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Doing Sensory Ethnography; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.L.; Okun, M.A. Using the Caregiver System Model to Explain the Resilience-Related Benefits Older Adults Derive from Volunteering. In The Resilience Handbook: Approaches to Stress and Trauma; Kent, M., Davis, M.C., Reich, J.W., Eds.; Routledge: England, UK, 2014; pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerroos, O.; Jukka, J. Etnologinen kenttatyo ja tutkimus: Metodin monimuotoisuuden pohdintaa ja esimerkkitapauksia. Ethnos Toimite 2014, 17, 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.; Ngunjiri, F.; Hernandez, K.-A.C. Collaborative Autoethnography, 1st ed.; Routledge: England, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, A.; Austin, J. Autoethnography and Teacher Development. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. Annu. Rev. 2007, 2, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adigüzel, I.B.; Göktürk, M. Using the Solution Focused Approach in School Counselling. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 10, 3278–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.S. Examining the Effectiveness of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2007, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.; Bochner, A.P. Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity. Researcher as Subject. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Teoksessa, N., Denzin, K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 733–768. [Google Scholar]

- Vitikka, E.; Krokfors, L.; Hurmerinta, E. Finnish National Core Curriculum. In Miracle of Education; Sense: Helsinki, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tullis, J.A. Self and Others–Ethics in Autoethnographic Research. In Handbook of Autoethnography; Jones, S.H., Adams, T.E., Ellis, C., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 244–261. [Google Scholar]

- Aromaa, J.; Tiili, M.L. Empatia ja Ruumiillinen Tieto Etnografisessa Tutkimuksessa. In Kansatieteen Päivät; Ethnos ry: Helsinki, Finland, 2014; pp. 258–283. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, I. Doing autoethnography: Facing challenges, taking choices, accepting responsibilities. Qual. Inq. 2018, 24, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviniemi, K. Laadullinen Tutkimus Prosessina. In Ikkunoita Tutkimusmetodeihin 2, Näkökulmia Aloittelevalle Tutkijalle Tutkimuksen Teoreettisiin Lähtökohtiin ja Analyysimenetelmiin; Aaltola, J., Valli, R., Eds.; PS-Kustannus: Jyvaskyla, Finland, 2018; pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pietikäinen, S.; Mäntynen, A. Kurssi Kohti Diskurssia; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin, M.J.; Brown, S.L.; Dillard, A.J.; Smith, D.M. Giving to Others and the Association Between Stress and Mortality. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zautra, A.J. Resilience is Social, after all. In The resilience Handbook; Kent, M., Davis, M.C., Reich, J.W., Eds.; Approaches to Stress and Trauma; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pantic, N.; Wubbels, T.; Mainhard, T. Teacher Competence as a Basis for Teacher Education: Comparing Views of Teachers and Teacher Educators in Five Western Balkan Countries. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2011, 55, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, T.; Pietarinen, J.; Toom, A.; Pyhalto, K. Haluanko, Osaanko ja Pystynko Oppimaan Taitavasti Yhdessa Muiden Kanssa? Opettajan Ammatillisen Toimijuuden Kehittyminen. In Kansankynttila Keinulaudalla–Miten Tulevaisuudessa Opitaan ja Opetetaan? Cantell, H., Kallioniemi, A., Eds.; PS-Kustannus: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2016; pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen, H.L.T.; Aho, J. Ope ei Saa Oppia; Opettajankoulutuksen Jatkumon Kehittäminen; Jyväskylän Yliopisto, Koulutuksen Tutkimuslaitos: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, J.; McLeod, J. How effective is workplace counselling. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2001, 1, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunonen-Ilmonen, M. Työnohjaus–Toiminnan Laadunhallinnan Varmistaja; WSOY: Helsinki, Finland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ruutu, S.; Salmimies, R. Työnohjaajan Opas. Valmentava ja Ratkaisukeskeinen Ote; Talentum: Helsinki, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, Y.; Pieni, A. Tie Hyvään Elämään Traumaattisen Kokemuksen Jälkeen; Bookwell Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bannink, F.P. Solution-Focused conflict management in teams and in Organisation. InterAction 2009, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, B. Solution-Focused Therapy; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Happiness, flow, and economic equality. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 1163–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suoninen, E. Näkökulma Sosiaalisen Todellisuuden Rakentumiseen. In Diskurssianalyysi Liikkeessä; Jokinen, A., Juhila, K., Suoninen, E., Eds.; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 1999; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. Todellisuuden Sosiaalinen Rakentuminen; Tiedonsosiologinen Tutkielma; Gaudeamus: Helsinki, Finland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- de Saussure, F. Course of Generel Linguistic; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Archeology of Knowledge; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kallasvuo, A.; Koski, A.; Kyrönseppä, U.; Kärkkäinen, M. Työyhteisön Työnohjaus; Kärkkäinen, M., Ed.; Jyväskylän Ammattikorkeakoulu: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bovey, W.H.; Hede, A. Resistance to organisational change: The role of defence mechanisms. J. Manag. Psychol. 2001, 16, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. Autoethnography as Method; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C.; Adams, T.E.; Bochner, A.P. Autoethnography: An Overview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 12, 10. [Google Scholar]

| Discourse | Meanings | Examples from Researchers’ Notes | Examples from Student Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| timeliness | timely support (scaffolding) | “That would mean utilizing timeliness, zone of proximal development and always scaffolding.” | “Today I especially needed support for my well-being and coping.” |

| meaningfulness | experiences of meaningfulness | “The stories were touching and beautiful and conveyed the feeling that one’s work is meaningful.” | “These moments are very important for the beginning of my career.” |

| encounters | willingness to face others genuinely | “...the respectful way they spoke about pupils and meeting with parents made me feel that it was a group of experts, not a group of students working on an assignment.” | “I think our discussion about the disadvantages of the profession has been very honest, respectful and open during the work counselling meetings.” |

| solution-focused level | giving guidance without giving answers | “...instead, one could think about what one can do despite shortage...” | “During the practice period, reinforcement was provided for issues that were relevant to me.” |

| collegiality/shared expertise | -support expected from colleagues -sharing the daily life -sharing ideas | “... they openly talk about their uncertainties and situations that they have managed well.” | “These moments are very important for the beginning of my career. I am still so uncertain of the things I do. Encouragement and peer support are always useful.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piispanen, M.; Meriläinen, M. Teaching Is a Story Whose First Page Matters—Teacher Counselling as Part of Teacher Growth. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120862

Piispanen M, Meriläinen M. Teaching Is a Story Whose First Page Matters—Teacher Counselling as Part of Teacher Growth. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120862

Chicago/Turabian StylePiispanen, Maarika, and Merja Meriläinen. 2022. "Teaching Is a Story Whose First Page Matters—Teacher Counselling as Part of Teacher Growth" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120862