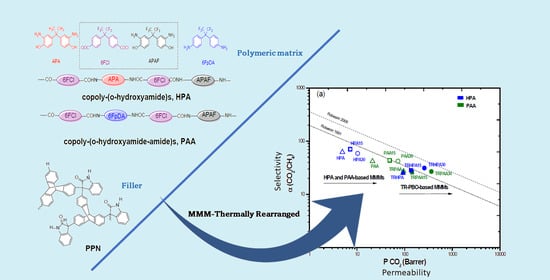

Thermally Rearranged Mixed Matrix Membranes from Copoly(o-hydroxyamide)s and Copoly(o-hydroxyamide-amide)s with a Porous Polymer Network as a Filler—A Comparison of Their Gas Separation Performances

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of 6FCl Acid Dichloride

2.3. Synthesis of Polyamides

2.4. Synthesis of the Porous Polymer Network as a Disperse Phase

2.5. Membrane Manufature

2.6. Thermal Rearrangement

2.7. Characterization of the Membranes

2.8. Gas Permeability Measurements

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Thermal Properties of the Membranes

3.2. Chemical and Physical Properties of the Membranes

3.3. Morphological Properties of the Membranes

3.4. Mechanical Properties of the Membranes

3.5. Calculation of the Fractional Free Volume of the Membranes

3.6. Gas Transport Properties of the Membranes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosal, K.; Freeman, B.D. Gas Separation Using Polymer Membranes: An Overview. Polym. Adv. Technol. 1994, 5, 673–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhnen, A.; Dietrich, D.; Millan, S.; Janiak, C. Role of Filler Porosity and Filler/Polymer Interface Volume in Metal-Organic Framework/Polymer Mixed-Matrix Membranes for Gas Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 33589–33600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robeson, L.M. Polymer Membranes for Gas Separation. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1999, 4, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Chung, T.; Lai, J. A Review of Polymeric Composite Membranes for Gas Separation and Energy Production. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 97, 101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E.; Golemme, G. Membrane Gas Separation: A Review/State of the Art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4638–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Smith, S.J.D.; Konstas, K.; Doherty, C.M.; Easton, C.D.; Park, J.; Yoon, H.; Wang, H.; Freeman, B.D.; Hill, M.R. Synergistically Improved PIM-1 Membrane Gas Separation Performance by PAF-1 Incorporation and UV Irradiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 10107–10119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Bee, S.; Bhargava, S. Membrane-Based Gas Separation: Principle, Applications and Future Potential. Chem. Eng. Dig. 2014, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Galizia, M.; Chi, W.S.; Smith, Z.P.; Merkel, T.C.; Baker, R.W.; Freeman, B.D. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Polymers and Mixed Matrix Membranes for Gas and Vapor Separation: A Review and Prospective Opportunities. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 7809–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria-Benavides, M.; David, O.; Johnson, T.; Łozińska, M.M.; Orsi, A.; Wright, P.A.; Mastel, S.; Hillenbrand, R.; Kapteijn, F.; Gascon, J. High Performance Mixed Matrix Membranes (MMMs) Composed of ZIF-94 Filler and 6FDA-DAM Polymer. J. Memb. Sci. 2018, 550, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khdhayyer, M.R.; Esposito, E.; Fuoco, A.; Monteleone, M.; Giorno, L.; Jansen, J.C.; Attfield, M.P.; Budd, P.M. Mixed Matrix Membranes Based on UiO-66 MOFs in the Polymer of Intrinsic Microporosity PIM-1. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 173, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Lugo, C.; Suárez-García, F.; Hernández, A.; Miguel, J.A.; Lozano, Á.E.; De La Campa, J.G.; Álvarez, C. New Materials for Gas Separation Applications: Mixed Matrix Membranes Made from Linear Polyimides and Porous Polymer Networks Having Lactam Groups. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 9585–9595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Martínez, S.; Álvarez, C.; Hernández, A.; Miguel, J.A.; Lozano, Á.E. Mixed Matrix Membranes Loaded with a Porous Organic Polymer Having Bipyridine Moieties. Membranes 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Iglesias, B.; Suárez-García, F.; Aguilar-Lugo, C.; González Ortega, A.; Bartolomé, C.; Martínez-Ilarduya, J.M.; De La Campa, J.G.; Lozano, Á.E.; Álvarez, C. Microporous Polymer Networks for Carbon Capture Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26195–26205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQahtani, M.S.; Mezghani, K. Thermally Rearranged Polypyrrolone Membranes for High-Pressure Natural Gas Separation Applications. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 51, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Palacio, L.; Muñoz, R.; Prádanos, P.; Hernandez, A. Recent Advances in Membrane-Based Biogas and Biohydrogen Upgrading. Processes 2022, 10, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Aguilar Lugo, C.; Rodríguez, S.; Palacio, L.; Lozano, E.; Prádanos, P.; Hernandez, A. Enhancement of CO2/CH4 Permselectivity via Thermal Rearrangement of Mixed Matrix Membranes Made from an o-Hydroxy Polyamide with an Optimal Load of a Porous Polymer Network. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 247, 116895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Lugo, C.; Lee, W.H.; Miguel, J.A.; De La Campa, J.G.; Prádanos, P.; Bae, J.Y.; Lee, Y.M.; Álvarez, C.; Lozano, Á.E. Highly Permeable Mixed Matrix Membranes of Thermally Rearranged Polymers and Porous Polymer Networks for Gas Separations. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 5224–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J.D.; Hou, R.; Lau, C.H.; Konstas, K.; Kitchin, M.; Dong, G.; Lee, J.; Lee, W.H.; Seong, J.G.; Lee, Y.M.; et al. Highly Permeable Thermally Rearranged Mixed Matrix Membranes (TR-MMM). J. Memb. Sci. 2019, 585, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.P.; Czenkusch, K.; Wi, S.; Gleason, K.L.; Hernández, G.; Doherty, C.M.; Konstas, K.; Bastow, T.J.; Álvarez, C.; Hill, A.J.; et al. Investigation of the Chemical and Morphological Structure of Thermally Rearranged Polymers. Polymer 2014, 55, 6649–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, A.E.; de Abajo, J.; de la Campa, J.G. Synthesis of Aromatic Polyisophthalamides by in Situ Silylation of Aromatic Diamines. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 2507–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.E.; De Abajo, J.; De La Campa, J.G. Quantum Semiempirical Study on the Reactivity of Silylated Diamines in the Synthesis of Aromatic Polyamides. Macromol. Theory Simul. 1998, 7, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Torres-Cuevas, E.S.; González-Ortega, A.; Palacio, L.; Lozano, Á.E.; Freeman, B.D.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A. Gas Separation by Mixed Matrix Membranes with Porous Organic Polymer Inclusions within O-Hydroxypolyamides Containing m-Terphenyl Moieties. Polymers 2021, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezakazemi, M.; Ebadi Amooghin, A.; Montazer-Rahmati, M.M.; Ismail, A.F.; Matsuura, T. State-of-the-Art Membrane Based CO2 Separation Using Mixed Matrix Membranes (MMMs): An Overview on Current Status and Future Directions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 817–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Sanip, S.M.; Ng, B.C.; Aziz, M. Recent Advances of Inorganic Fillers in Mixed Matrix Membrane for Gas Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 81, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Carmona, J.; Freeman, B.D.; Palacio, L.; González-Ortega, A.; Prádanos, P.; Lozano, Á.E.; Hernandez, A. Free Volume and Permeability of Mixed Matrix Membranes Made from a Terbutil-M-Terphenyl Polyamide and a Porous Polymer Network. Polymers 2022, 14, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Z.P.; Sanders, D.F.; Ribeiro, C.P.; Guo, R.; Freeman, B.D.; Paul, D.R.; McGrath, J.E.; Swinnea, S. Gas Sorption and Characterization of Thermally Rearranged Polyimides Based on 3,3′-Dihydroxy-4,4′-Diamino-Biphenyl (HAB) and 2,2′-Bis-(3,4-Dicarboxyphenyl) Hexafluoropropane Dianhydride (6FDA). J. Memb. Sci. 2012, 415–416, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijmans, J.G.; Baker, R.W. The Solution-Diffusion Model: A Review. J. Memb. Sci. 1995, 107, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, B.; Cuadrado, P.; Marcos-Fernández, Á.; de la Campa, J.G.; Tena, A.; Prádanos, P.; Palacio, L.; Lee, Y.M.; Alvarez, C.; Lozano, Á.E.; et al. Thermally Rearranged Polybenzoxazoles Made from Poly(Ortho-Hydroxyamide)s. Characterization and Evaluation as Gas Separation Membranes. React. Funct. Polym. 2018, 127, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, T.D.M.; Venna, S.R.; Dahe, G.; Hopkinson, D.P.; El-Kaderi, H.M.; Sekizkardes, A.K. Incorporation of Benzimidazole Linked Polymers into Matrimid to Yield Mixed Matrix Membranes with Enhanced CO2/N2 Selectivity. J. Memb. Sci. 2018, 554, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, G.J.; Shanks, R.A. The Influence of Filler Particles on the Mobility of Polymer Molecules. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A-Chem. 1982, 17, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccormick, H.W.; Brower, F.R.T.; Kik, L.E.O. The Effect of Molecular Weight Distribution on the Physical Properties of Polystyrene. Polym. Sci. 1959, 135, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.F.; Khulbe, K.C.; Matsuura, T. Gas Separation Membranes: Polymeric and Inorganic; Springer: Ottawa, ON, Canada; New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9783319010953. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu, A.; Miyazaki, T.; Ikeda, K. Interpretation of D-Spacing Determined by Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering in 6FDA-Based Polyimide by Molecular Modeling. J. Memb. Sci. 2000, 166, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.T.; Koros, W.J. Non-Ideal Effects in Organic-Inorganic Materials for Gas Separation Membranes. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 739, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroon, M.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Matsuura, T.; Montazer-Rahmati, M.M. Performance Studies of Mixed Matrix Membranes for Gas Separation: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 75, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Paul, D.R.; Freeman, B.D. Gas Permeation and Mechanical Properties of Thermally Rearranged (TR) Copolyimides. Polymer 2016, 82, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, N.; Robertson, G.P.; Song, J.; Pinnau, I.; Guiver, M.D. High-Performance Carboxylated Polymers of Intrinsic Microporosity (PIMs) with Tunable Gas Transport Properties. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 6038–6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venna, S.R.; Lartey, M.; Li, T.; Spore, A.; Kumar, S.; Nulwala, H.B.; Luebke, D.R.; Rosi, N.L.; Albenze, E. Fabrication of MMMs with Improved Gas Separation Properties Using Externally-Functionalized MOF Particles. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 5014–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jo, H.J.; Han, S.H.; Park, C.H.; Kim, S.; Budd, P.M.; Lee, Y.M. Mechanically Robust Thermally Rearranged (TR) Polymer Membranes with Spirobisindane for Gas Separation. J. Memb. Sci. 2013, 434, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breck, D.W. Zeolite Molecular Sieves: Structure, Chemistry and Use. Anal. Chim. Acta 1975, 75, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Torres-Cuevas, E.S.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Freeman, B.D.; Lozano, Á.E.; Hernández, A.; Comesaña-Gándara, B. Gas Permeability, Fractional Free Volume and Molecular Kinetic Diameters: The Effect of Thermal Rearrangement on Ortho-Hydroxy Polyamide Membranes Loaded with a Porous Polymer Network. Membranes 2022, 12, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, R.; Koros, W.J. Factors Controlling Successful Formation of Mixed-Matrix Gas Separation Materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2000, 39, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, C.M.; Singh, A.; Koros, W.J. Tailoring Mixed Matrix Composite Membranes for Gas Separations. J. Memb. Sci. 1997, 137, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. The Upper Bound Revisited. J. Memb. Sci. 2008, 320, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. Correlation of Separation Factor versus Permeability for Polymeric Membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 1991, 62, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Continuous Phase | Neat Membranes | TR-PBO Membranes |

|---|---|---|

| Copoly-o-hydroxyamide-amide (APAF-6FpDA-6FCl) | PAA | TR-PAA |

| PAA15 | TR-PAA15 | |

| PAA30 | TR-PAA30 | |

| Copoly-o-hydroxyamide (APAF-APA-6FCl) | HPA | TR-HPA |

| HPA15 | TR-HPA15 | |

| HPA30 | TR-HPA30 |

| Tg (°C) | Tg (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PAA | 283 | TRPAA | 304 |

| PAA15 | 287 | TRPAA15 | 306 |

| PAA30 | 292 | TRPAA30 | 304 |

| HPA | 279 | TRHPA | 296 |

| HPA15 | 290 | TRHPA15 | 298 |

| HPA30 | 288 | TRHPA30 | 293 |

| Polymer | Density (g/cm3) | dspacing (nm) | Polymer | Density (g/cm3) | dspacing (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAA | 1.49 | 0.53 | HPA | 1.42 | 0.58 |

| PAA15 | 1.41 | 0.53 | HPA15 | 1.39 | 0.57 |

| PAA30 | 1.35 | 0.52 | HPA30 | 1.36 | 0.57 |

| TR-PAA | 1.44 | 0.55 | TR-HPA | 1.42 | 0.59 |

| TR-PAA15 | 1.44 | 0.54 | TR-HPA15 | 1.33 | 0.59 |

| TR-PAA30 | 1.35 | 0.55 | TR-HPA30 | 1.32 | 0.60 |

| (APAF-APA-6FCl) + PPN | Maximum Stress (MPa) | Strain (%) | Young Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPA | 84 ± 7 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| HPA15 | 51 ± 15 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| HPA30 | 55 ± 15 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| TRHPA | 68 ± 12 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| TRHPA15 | 52 ± 17 | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| TRHPA30 | 22 ± 18 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| (APAF-6FpDA-6FCl) + PPN | Maximum Stress (MPa) | Strain (%) | Young Modulus (GPa) |

| PAA | 71.4 ± 3.6 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| PAA15 | 60.6 ± 9.9 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| PAA30 | 37.6 ± 7.7 | 3.2 ±0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| TRPAA | 88.6 ± 7.9 | 10.1 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| TRPAA15 | 62.5 ± 12 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| TRPAA30 | 49.3 ± 5.6 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| lnA + a FFV | b FFV | c FFV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before TR | PAA | −11.65 ± 1.5 | 10.1 ± 1.5 | −1.9 ± 0.3 |

| PAA15 | −12.95 ± 2.9 | 11.0 ± 1.7 | −2.0 ± 0.3 | |

| PAA30 | −12.74 ± 2.8 | 11.0 ± 2.8 | −2.0 ± 0.4 | |

| After TR | TRPAA | −12.39 ± 4.1 | 10.5 ± 4.1 | −1.9 ± 0.4 |

| TRPAA15 | −13.37 ± 4.8 | 11.1 ± 1.8 | −2.0 ± 0.5 | |

| TRPAA30 | −13.82 ± 5.0 | 11.6 ± 1.8 | −2.0 ± 0.5 | |

| Before TR | HPA | −11.61 ± 2.7 | 10.1 ± 1.8 | −1.9 ± 0.5 |

| HPA15 | −14.01 ± 3.4 | 11.7 ± 2.0 | −2.1 ± 0.4 | |

| HPA30 | −13.40 ± 2.9 | 11.2 ± 1.7 | −2.1 ± 0.4 | |

| After TR | TRHPA | −12.28 ± 3.5 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | −1.8 ± 0.4 |

| TRHPA15 | −13.39 ± 4.0 | 11.1 ± 1.7 | −2.0 ± 0.5 | |

| TRHPA30 | −13.82 ± 4.1 | 11.6 ± 1.8 | −2.0 ± 0.3 |

| f (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Before TR | PAA | 9.44 |

| PAA15 | 17.44 | |

| PAA30 | 17.44 | |

| After TR | TR-PAA | 18.46 |

| TR-PAA15 | 23.96 | |

| TR-PAA30 | 27.46 | |

| Before TR | HPA | 10.50 |

| HPA15 | 25.00 | |

| HPA30 | 20.00 | |

| After TR | TR-HPA | 13.71 |

| TR-HPA15 | 21.21 | |

| TR-HPA30 | 24.71 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soto, C.; Comesaña-Gandara, B.; Marcos, Á.; Cuadrado, P.; Palacio, L.; Lozano, Á.E.; Álvarez, C.; Prádanos, P.; Hernandez, A. Thermally Rearranged Mixed Matrix Membranes from Copoly(o-hydroxyamide)s and Copoly(o-hydroxyamide-amide)s with a Porous Polymer Network as a Filler—A Comparison of Their Gas Separation Performances. Membranes 2022, 12, 998. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12100998

Soto C, Comesaña-Gandara B, Marcos Á, Cuadrado P, Palacio L, Lozano ÁE, Álvarez C, Prádanos P, Hernandez A. Thermally Rearranged Mixed Matrix Membranes from Copoly(o-hydroxyamide)s and Copoly(o-hydroxyamide-amide)s with a Porous Polymer Network as a Filler—A Comparison of Their Gas Separation Performances. Membranes. 2022; 12(10):998. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12100998

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoto, Cenit, Bibiana Comesaña-Gandara, Ángel Marcos, Purificación Cuadrado, Laura Palacio, Ángel E. Lozano, Cristina Álvarez, Pedro Prádanos, and Antonio Hernandez. 2022. "Thermally Rearranged Mixed Matrix Membranes from Copoly(o-hydroxyamide)s and Copoly(o-hydroxyamide-amide)s with a Porous Polymer Network as a Filler—A Comparison of Their Gas Separation Performances" Membranes 12, no. 10: 998. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12100998