Synthesis and Characterization of Late Transition Metal Complexes of Mono-Acetate Pendant Armed Ethylene Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocycles with Promise as Oxidation Catalysts for Dye Bleaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ligand Synthesis and Metal Complexation

2.2. X-ray Crystallography

2.3. Cyclic Voltammetry

2.4. Kinetic Stability

| Ligand | Pseudo-First Order Half-Life for Decomplexation at Various Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 °C, 1 M HCl | 30 °C, 1 M HClO4 | 40 °C, 1 M HClO4 | 50 °C 5M HCl | 70 °C, 5M HCl | 90 °C, 5M HCl | References | |

L1 L1 | 9 min | 33.94 h | 16.0 h | <1 min | This work | ||

L2 L2 | 18.5 days | 6.95 days | 9.01 h | This work | |||

H2Bcyclen H2Bcyclen | <1 min | [31] | |||||

Me2Bcyclen Me2Bcyclen | 36 min | 30 h | <1 min | [57] | |||

H2Bcyclam H2Bcyclam | 11.8 min | [60] | |||||

Me2EBC Me2EBC | >6 years | 7.3 day | 79 min | [17,57] | |||

Py1Me1Bcyclam Py1Me1Bcyclam | 14.7 min | <2 min | [17] | ||||

CB-TE2A CB-TE2A | 154 h | [60] | |||||

CB-DO2A CB-DO2A | 4 h | [34,60] | |||||

H2B13N4 H2B13N4 | 4.8 h | [18] | |||||

Me2B13N4 Me2B13N4 | 7.7 day | 30.1 min | <2 min | [31] | |||

TETA TETA | 3.2 h | 4.5 min | [60] | ||||

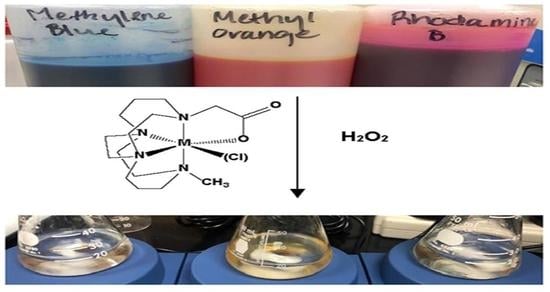

2.5. Dye Degradation Studies

3. Experimental

3.1. General Procedures

3.2. Synthesis

3.2.1. Synthesis of Ligands L1 and L2

3.2.2. Step IV. Synthesis of Metal Complexes

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Dye Bleaching Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Schäfer, F.P.; Schmidt, W.; Volze, J. Organic dye solution laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1966, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustroph, H.S.M.; Bressau, V. Current Developments in Optical Data Storage with Organic Dyes. Angew. Chem. 2006, 45, 2016–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; Chang, T.-F.M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Sone, M.; Hsu, Y.-J. Mechanistic Insights into Photodegradation of Organic Dyes Using Heterostructure Photocatalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tkaczyk, A.; Mitrowska, K.; Posyniak, A. Synthetic organic dyes as contaminants of the aquatic environment and their implications for ecosystems: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epling, G.A.; Lin, C. Photoassisted bleaching of dyes utilizing TiO2 and visible light. Chemosphere 2002, 46, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, R.; Guo, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, J. Effects of chloride ions on bleaching of azo dyes by Co2+/oxone regent: Kinetic analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 190, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, P.; Neves, C.M.B.; Simões, M.M.Q.; Neves, M.D.G.P.M.S.; Cocco, G.S. Immobilized Lignin Peroxidase-Like Metalloporphyrins as Reusable Catalysts in Oxidative Bleaching of Industrial Dyes. Molecules 2016, 21, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, M.C.; Antonin, V.S.; Souza, F.M.; Aveiro, L.R.; Pinheiro, V.S.; Gentil, T.C.; Lima, T.S.; Moura, J.P.C.; Silva, C.R.; Lucchetti, L.E.B.; et al. Decontamination of wastewater containing contaminants of emerging concern by electrooxidation and Fenton-based processes—A review on the relevance of materials and methods. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, V.M.; Evstrop’ev, S.K.; Starodubtsev, A.M. Photocatalytic degradation and sorption of methylene blue on the surface of metal oxides in aqueous solutions of the dye. Opt. Spectrosc. 2017, 123, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.S.; Wu, T.Y.; Juan, J.C.; Teh, C.Y. Recent developments of metal oxide semiconductors as photocatalysts in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for treatment of dye waste-water. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2011, 86, 1130–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, M.G.; Nakagaki, S.; Ucoski, G.M.; Wypych, F.; Machado, G.S. Comparison between catalytic activities of two zinc layered hydroxide salts in brilliant green organic dye bleaching. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 541, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamraiz, U.; Hussain, R.A.; Badshah, A.; Raza, B.; Saba, S. Functional metal sulfides and selenides for the removal of hazardous dyes from Water. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 159, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puga, A.V.; Barka, N.; Imizcoz, M. Simultaneous H2 Production and Bleaching via Solar Photoreforming of Model Dye-polluted Wastewaters on Metal/Titania. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 1513–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.G.; Zhang, G. A novel mixed-phase TiO2/kaolinite composites and their photocatalytic activity for degradation of organic contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 172, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shircliff, A.D.; Burke, B.P.; Davilla, D.J.; Burgess, G.E.; Okorocha, F.A.; Shrestha, A.; Allbritton, E.M.A.; Nguyen, P.T.; Lamar, R.L.; Jones, D.G.; et al. An ethylene cross-bridged pentaazamacrocycle and its Cu2+ complex: constrained ligand topology and excellent kinetic stability. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 7519–7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, T.J.; Alcock, N.W.; Clase, H.J.; Seib, L.L.; Busch, D.H. Synthesis, characterization, and X-ray crystal structures of cobalt(II) and cobalt(III) complexes of four topologically constrained tetraazamacrocycles. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2002, 337, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.G.; Wilson, K.R.; Cannon-Smith, D.J.; Shircliff, A.D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Prior, T.J.; Yin, G.; Hubin, T.J. Synthesis, Structural Studies, and Oxidation Catalysis of the Late First-Row-Transition-Metal Complexes of a 2-Pyridylmethyl Pendant Armed Ethylene Cross-Bridged Cyclam. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 2221–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, A.Y.; Fiamengo, A.L.; Ferdani, R.; Wadas, T.J.; Hill, D.C.; Peng, Y.; Heroux, K.J.; Golen, J.A.; Rheingold, A.L.; Anderson, C.J.; et al. Isomeric Trimethylene and Ethylene Pendant-armed Cross-bridged Tetraazamacrocycles and in Vitro/in Vivo Comparisions of their Copper(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 3078–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A.N.; Freeman, T.N.C.; Roewe, K.D.; Cockriel, D.L.; Hasley, T.R.; Maples, R.D.; Allbritton, E.M.A.; D’Huys, T.; Loy, T.v.; Burke, B.P.; et al. Acetate as a model for aspartate-based CXCR4 chemokine receptor binding of cobalt and nickel complexes of cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycles. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 2785–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, T.J.; McCormick, J.M.; Collinson, S.R.; Buchalova, M.; Perkins, C.M.; Alcock, N.W.; Kahol, P.K.; Raghunathan, A.; Busch, D.H. New Iron(II) and Manganese(II) Complexes of Two Ultra-Rigid, Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocycles for Catalysis and Biomimicry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2512–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Kwong, H.-K.; Lau, T.-C. Catalytic oxidation of water and alcohols by a robust iron(iii) complex bearing a cross-bridged cyclam ligand. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12189–12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, A.; Esposito, R.; Gatto, G.; Cucciolito, M.E.; Tuzi, A.; Macchioni, A.; Ruffo, F. Iron(III) Complexes with Cross-Bridged Cyclams: Synthesis and Use in Alcohol and Water Oxidation Catalysis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 3304–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, T.J.; McCormick, J.M.; Collinson, S.R.; Alcock, N.W.; Clase, H.J.; Busch, D.H. Synthesis and X-ray crystal structures of iron(II) and manganese(II) complexes of unsubstituted and benzyl substituted cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycles. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2003, 346, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Danby, A.M.; Kitko, D.; Carter, J.D.; Scheper, W.M.; Busch, D.H. Olefin Epoxidation by Alkyl Hydroperoxide with a Novel Cross-Bridged Cyclam Manganese Complex: Demonstration of Oxygenation by Two Distinct Reactive Intermediates. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, G.C.; Danby, A.M.; Kitko, D.; Carter, J.D.; Scheper, W.M.; Busch, D.H. Oxidative reactivity difference among the metal oxo and metal hydroxo moieties: pH dependent hydrogen abstraction by a manganese(IV) complex having two hydroxide ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16245–16253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Geiger, R.A.; Yin, G.; Busch, D.H.; Jackson, T.A. Oxo- and Hydroxomanganese(IV) Adducts: A Comparative Spectroscopic and Computational Study. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 7530–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Mei, F.; Xiong, H.; Yin, G. Lewis-Acid-Promoted Stoichiometric and Catalytic Oxidations by Manganese Complexes Having Cross-Bridged Cyclam Ligand: A Comprehensive Study. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 5418–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, D.H.; Collinson, S.R.; Hubin, T. Catalysts and methods for Catalytic Oxidation. US Patent 6,906,189, 14 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Coats, K.L.; Chen, Z.Q.; Hubin, T.J.; Yin, G.C. Influence of Calcium(II) and Chloride on the Oxidative Reactivity of a Manganese(II) Complex of a Cross-Bridged Cyclen Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 11937–11947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, S.M.; Wilson, K.R.; Jones, D.G.; Reinheimer, E.W.; Archibald, S.J.; Prior, T.J.; Ayala, M.A.; Foster, A.L.; Hubin, T.J.; Green, K.N. Increase of Direct C–C Coupling Reaction Yield by Identifying Structural and Electronic Properties of High-Spin Iron Tetra-azamacrocyclic Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 8890–8902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, D.L.; Jones, D.G.; Roewe, K.D.; Gorbet, M.J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.Q.; Prior, T.J.; Archibald, S.J.; Yin, G.C.; Hubin, T.J. Synthesis, structural studies, kinetic stability, and oxidation catalysis of the late first row transition metal complexes of 4,10-dimethyl-1,4,7,10-tetraazabicyclo [6.5.2]pentadecane. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12210–12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, D.H. The Compleat Coordination Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.J.; Wadas, T.J.; Wong, E.H.; Weisman, G.R. Cross-bridged Macrocyclic Chelators for Stable Complexation of Copper Radionuclides for PET Imaging. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 52, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boswell, C.A.; Sun, X.; Niu, W.; Weisman, G.R.; Wong, E.H.; Rheingold, A.L.; Anderson, C.J. Comparative in vivo stability of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged and conventional tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdani, R.; Stigers, D.J.; Fiamengo, A.L.; Wei, L.; Li, B.T.Y.; Golen, J.A.; Rheingold, A.L.; Wiesman, G.R.; Wong, E.H.; Anderson, C.J. Syntheis, Cu(II) complexation, 64Cu-labeling and biological evaluation of cross-bridged cyclam chelators with phosphonate pendant arms. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 1938–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heroux, K.J.; Woodin, K.S.; Tranchemontagne, D.J.; Widger, P.C.B.; Southwick, E.; Wong, E.H.; Weisman, G.R.; Tomellini, S.A.; Wadas, T.J.; Anderson, C.J.; et al. The long and short of it: The influence of N-carboxyethyl versus N-carboxymethyl pendant arms on in vitro and in vivo behavior of copper complexes of cross-bridged tetraamine macrocycles. Dalton Trans. 2007, 2159–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sprague, J.E.; Peng, Y.; Fiamengo, A.L.; Woodin, K.S.; Southwick, E.A.; Weisman, G.R.; Wong, E.H.; Golen, J.A.; Rheingold, A.L.; Anderson, C.J. Synthesis, Characterization and In Vivo Studies of Cu(II)-64-Labeled Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocycle-amide Complexes as Models of Peptide Conjugate Imaging Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 2527–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wuest, M.; Weisman, G.R.; Wong, E.H.; Reed, D.P.; Boswell, C.A.; Motekaitis, R.; Martell, A.E.; Welch, M.J.; Anderson, C.J. Radiolabeling and in vivo behavior of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged cyclam ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, B.P.; Miranda, C.S.; Lee, R.E.; Renard, I.; Nigam, S.; Clemente, G.S.; D’Huys, T.; Ruest, T.; Domarkas, J.; Thompson, J.A.; et al. Cu PET Imaging of the CXCR4 Chemokine Receptor Using a Cross-Bridged Cyclam Bis-Tetraazamacrocyclic Antagonist. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valks, G.C.; McRobbie, G.; Lewis, E.A.; Hubin, T.J.; Hunter, T.M.; Sadler, P.J.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E.; Archibald, S.J. Configurationally restricted bismacrocyclic CXCR4 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6162–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Nicholson, G.; Greenman, J.; Madden, L.; McRobbie, G.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E.; Ullom, R.; Maples, D.L.; Maples, R.D.; et al. Binding Optimization through Coordination Chemistry: CXCR4 Chemokine Receptor Antagonists from Ultrarigid Metal Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3416–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Huskens, D.; Daelemans, D.; Mewis, R.E.; Garcia, C.D.; Cain, A.N.; Carder Freeman, T.N.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E.; Schols, D.; et al. CXCR4 chemokine receptor antagonists: nickel(II) complexes of configurationally restricted macrocycles. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 11369–11377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maples, R.D.; Cain, A.N.; Burke, B.P.; Silversides, J.D.; Mewis, R.; D’huys, T.; Schols, D.; Linder, D.P.; Archibald, S.J.; Hubin, T.J. Aspartate-based CXCR4 chemokine receptor binding of cross-bridged tetraazamacrocyclic copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes. Chem. A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 12916–12930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busch, D.H.; Collinson, S.R.; Hubin, T.J.; Perkins, C.M.; Labeque, R.; Williams, B.K.; Johnston, J.P.; Kitko, D.J.; Berkett-St Laurent, J.C.T.R. Bleach Compositions. US Patent 6,218,351, 17 April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, D.H.; Collinson, S.R.; Hubin, T.J.; Perkins, C.M.; Labeque, R.; Williams, B.K.; Johnston, J.P.; Kitko, D.J.; Berkett-St Laurent, J.C.T.R.; Burns, M.E. Bleach Compositions. US Patent 6,387,862, 14 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, D.H.; Collinson, S.R.; Hubin, T.J.P.C.M.; Labeque, R.W.B.K.; Johnston, J.P.; Kitko, D.J.; Berkett-St Laurent, J.C.T.R.; Burns, M.E. Bleach Compositions. US Patent 6,605,015, 19 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, D.H.C.S.R.; Hubin, T.J.; Perkins, C.M.; Labeque, R.; Williams, B.K.; Johnston, J.P.; Kitko, D.J.; Berkett-St Laurent, J.C.T.R. Bleach Compositions. US Patent 7,125,832, 24 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shircliff, A.D.; Wilson, K.R.; Smith, D.J.; Jones, D.G.; Hubin, T.J. Synthesis and characterization of pyridine-armed reinforced macrocycles and their transition metal complexes as potential oxidation catalysts. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Shircliff, A.D.; Wilson, K.R.; Cannon-Smith, D.J.; Jones, D.G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.Q.; Yin, G.C.; Prior, T.J.; Hubin, T.J. Synthesis, structural studies, and oxidation catalysis of the manganese(II), iron(II), and copper(II) complexes of a 2-pyridylmethyl pendant armed side-bridged cyclam. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2015, 59, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, K.R.; Cannon-Smith, D.J.; Burke, B.P.; Birdson, O.C.; Archibald, S.J.; Hubin, T.J. Synthesis and structural studies of two pyridine-armed reinforced cyclen chelators and their transition metal complexes. Polyhedron 2016, 114, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perkins, C.M.K. MRI Image Enhancement Compositions Containing Tetraazabicyclohexadecane Manganese Complexes; World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- AlHaddad, N.L.; Suh, J.-M.; Cordier, M.; Lim, M.H.; Royal, G.; Platas-Iglesias, C.; Bernard, H.; Tripier, R. Copper(II) and zinc(II) complexation with N-ethylene hydroxycyclams and consequences on the macrocyclic backbone configuration. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 8640–8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.H.W.; Hill, D.C.; Reed, D.P.; Rogers, M.E.; Condon, J.S.; Fagan, M.A.; Calabrese, J.C.; Lam, K.-C.; Guzei, I.A.; Rheingold, A.L. Synthesis and Characterization of Cross-Bridged Cyclams and Pendant-Armed Derivatives and Structural Studies of Their Copper(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 10561–10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, A.W.R.; Reedijk, J.; Rijn, J.V.; Verschoor, G.C. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen—sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua [1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 7, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkaew, R.T.; Harding, P.; Chastanet, G.; Guionneau, P.; Marchivie, M.; Harding, D.J. OctaDist: A Tool for Calculating Distortion Parameters in Spin Crossover and Coordination Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, T.J.; Alcock, N.W.; Clase, H.J.; Busch, D.H. Potentiometric titrations and nickel(II) complexes of four topologically constrained tetraazamacrocycles. Supramol. Chem. 2001, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, T.J.; Alcock, N.W.; Morton, M.D.; Busch, D.H. Synthesis, structure, and stability in acid of copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes of cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycles. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2003, 348, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, T.J.; Alcock, N.W.; Clase, H.J.; Busch, D.H. Crystallographic Characterization of Stepwise Changes in Ligand Conformations as Their Internal Topology Changes and Two Novel Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocyclic Copper(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 4435–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubin, T.J.; Collinson, S.R.; Alcock, N.W.; Busch, D.H. Ultra rigid cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycles as ligands—the challenge and the solution. Chem. Commun. 1998, 16, 1675–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodin, K.S.; Heroux, K.J.; Boswell, C.A.; Wong, E.H.; Weisman, G.R.; Niu, W.J.; Tomellini, S.A.; Anderson, C.J.; Zakharov, L.N.; Rheingold, A.L. Kinetic inertness and electrochemical behavior of copper(II) tetraazamacrocyclic complexes: Possible implications for in vivo stability. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 23, 4829–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krossing, I.R. Noncoordinating Anions - Fact or Fiction? A Survey of Likely Candidates. Angew. Chem. 2004, 43, 2066–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzal-Varela, R.P.; Tripier, R.; Valencia, L.; Maneiro, M.; Canle, M.; Platas-Iglesias, C.; Esteban-Gomez, D.; Iglesias, E. On the dissociation pathways of copper complexes relevant as PET imaging agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 236, 111951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Gupta, R. Encapsulation-Led Adsorption of Neutral Dyes and Complete Photodegradation of Cationic Dyes and Antipsychotic Drugs by Lanthanide-Based Macrocycles. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 7682–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.X.; Yin, G. Decolorization of Dye Pollutions by Manganese Complexes with Rigid Cross-Bridged Cyclam Ligands and Its Mechanistic Investigations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 12243–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadas, T.J.; Weisman, G.R.; Anderson, C.J. Coordinating Radiometals of Copper, Gallium, Indium, Yttrium, and Zirconium for PET and SPECT Imaging of Disease. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2858–2902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dolomanov, O.V.B.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [CoL1Cl]PF6 |

| Bond lengths: |

| Co(1)-Cl(1) 2.2854(7) Co(1)-N(4) 1.922(2) |

| Co(1)-O(1) 1.924(2) Co(1)-N(2) 1.931(2) |

| Co(1)-N(1) 1.939(2) Co(1)-N(3) 1.997(3) |

| Bond angles: |

| O(1)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 87.89(7) N(4)-Co(1)-N(1) 86.22(10) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(1) 87.43(9) N(4)-Co(1)-N(2) 89.26(10) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(2) 90.35(10) N(4)-Co(1)-N(3) 88.52(10) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(3) 97.77(9) N(2)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 178.21(8) |

| N(1)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 91.60(7) N(2)-Co(1)-N(1) 88.64(11) |

| N(1)-Co(1)-N(3) 171.70(11) N(2)-Co(1)-N(3) 84.87(12) |

| N(4)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 92.52(7) N(3)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 95.05(8) |

| N(4)-Co(1)-O(1) 173.64(9) N(4)-Co(1)-N(1) 86.22(10) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 87.89(7) N(4)-Co(1)-N(2) 89.26(10) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(1) 87.43(9) |

| [CuL1]PF6 |

| Bond lengths: |

| Cu(1)-O(1) 1.9522(11) Cu(1)-N(1) 1.9640(12) |

| Cu(1)-N(3) 1.9876(13) Cu(1)-O(1) 1.9522(11) |

| Cu(1)-N(2) 2.1891(13) |

| Bond angles: |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(3) 100.26 (5) N(3)-Cu(1)-N(4) 88.88(5) |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(2) 119.60(5) N(1)-Cu(1)-N(3) 171.41(5) |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(1) 85.39(5) N(1)-Cu(1)-N(2) 86.20(5) |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(4) 158.06(5) N(1)-Cu(1)-N(4) 88.09(5) |

| N(3)-Cu(1)-N(2) 85.38(5) N(4)-Cu(1)-N(2) 80.73(5) |

| [CoL2Cl]PF6 |

| Bond lengths: |

| Co(1)-O(1) 1.901(3) Co(1)-N(1) 1.986(4) |

| Co(1)-N(2) 2.002(4) Co(1)-N(4) 1.961(4) |

| Co(1)-N(3) 2.035(4) Co(1)-Cl(1) 2.3014(17) |

| Bond angles: |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(2) 88.92(15) N(1)-Co(1)-N(2) 86.96(16) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(3) 90.85(15) N(1)-Co(1)-N(3) 178.04(17) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(1) 87.26(16) N(1)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 85.55(12) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(4) 177.55(18) N(4)-Co(1)-N(2) 89.00(18) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 87.36(11) N(4)-Co(1)-N(3) 87.97(18) |

| N(2)-Co(1)-N(3) 93.48(17) N(4)-Co(1)-N(1) 93.94(19) |

| N(2)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 171.78(12) N(4)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 94.87(15) |

| N(3)-Co(1)-Cl(1) 93.90(13) N(1)-Co(1)-N(2) 86.96(16) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(2) 88.92(15) |

| O(1)-Co(1)-N(3) 90.85(15) |

| [CuL2]PF6 |

| Bond lengths: |

| Cu(1)-O(1) 1.941(3) Cu(1)-N(3) 2.219(3) |

| Cu(1)-N(1) 2.028(3) Cu(1)-N(4) 2.057(3) |

| Cu(1)-N(2) 2.049(3) Cu(1)-O(1) 1.941(3) |

| Bond angles: |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(1) 170.34(13) N(1)-Cu(1)-N(3) 86.27(13 |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(2) 91.23(12) N(1)-Cu(1)-N(4) 94.46(13) |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(3) 103.38(12) N(2)-Cu(1)-N(3) 93.48(12) |

| O(1)-Cu(1)-N(4) 86.65(12) N(2)-Cu(1)-N(4) 177.48(12) |

| N(1)-Cu(1)-N(2) 87.86(13) N(4)-Cu(1)-N(3) 85.69(13) |

| Complex | M1+/2+ Ered [V] | M1+/2+ E1/2 [V] (ΔE [mV]) | M2+/3+ E1/2 [V] (ΔE [mV]) | M3+/4+ E1/2 [V] (ΔE [mV]) | M3+/4+ Eox [V] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(Me2Bcyclen)Cl2 | ----- | ----- | +0.466 (70) | +1.232 (102) | ----- | [20] |

| Mn(Me2EBC)Cl2 | ----- | ------ | +0.585 (61) | +1.343 (65) | ----- | [20] |

| Mn(L1)Cl | −0.913 | ----- | +0.463 (60) | +1.235 (116) | +1.451 | This work |

| Mn(L2)Cl | ----- | ----- | +0.371 (87) | +1.328 (88) | ----- | This work |

| Fe(Me2Bcyclen)Cl2 | ----- | ----- | +0.036 (64) | ----- | ----- | [20] |

| Fe(Me2EBC)Cl2 | ----- | ----- | +0.110 (63) | ----- | ----- | [20] |

| Fe(L1)Cl | −0.526 | ----- | +0.037 (117) | ----- | +1.182 | This work |

| Fe(L2)Cl | −0.502 | ----- | +0.047 (87) | ----- | +1.210 | This work |

| Co(Me2Bcyclen)Cl2 | −2.202 | ----- | −0.157 (288) | ----- | +0.983 | [16] |

| Co(Me2EBC)Cl2 | −2.198 | ----- | +0.173 (103) | ----- | +1.051 | [16] |

| [Co(L1)Cl+] | ----- | ----- | −0.386 (156) | ----- | ----- | This work |

| [Co(L2)Cl+] | ----- | ----- | −0.157 (130) | ----- | ----- | This work |

| Ni(Me2Bcyclen)Cl2 | −2.036 | ----- | +0.863 (68) | ----- | +1.450 | [56] |

| Ni(Me2EBC)Cl2 | −1.894 | ----- | +0.991 (154) | ----- | +1.325 | [56] |

| [Ni(L1)Cl+] | ----- | ----- | +0.895 (161) | +1.373 (194) | ----- | This work |

| [Ni(L2)Cl+] | ----- | ----- | +1.030 (182) | ----- | ----- | This work |

| [Cu(Me2Bcyclen)Cl+] | −0.651 | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | [57] |

| [Cu(Me2EBC)Cl+] | ----- | −0.544 (97) | +1.530 (irreversible) | ----- | ----- | [57] |

| [Cu(L1)+] | * Ecat = −0.303 | −0.846 (104) | ----- | ----- | ----- | This work |

| [Cu(L2)+] | ----- | −1.025 (81) | ----- | ----- | ----- | This work |

| Catalyst | Average Conversion% For MB | Average TOF for MB (h−1) | Average Conversion% For MO | Average TOF for MO (h−1) | Average Conversion% For RhB | Average TOF for RhB (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O2 only | 3 | 0.018 | 2 | 0.034 | 2 | 0.002 |

| FeCl2 only | 3 | 0.111 | 97 | 0.926 | 9 | 0.055 |

| MnCl2 only | 3 | 0.003 | 27 | 0.518 | 2 | 0.047 |

| [MnL1Cl] | 91 | 1.050 | 77 | 2.034 | 37 | 0.327 |

| [FeL1Cl] | 49 | 1.289 | 89 | 2.568 | 90 | 0.626 |

| [MnL2Cl] | 100 | 1.657 | 93 | 10.749 | 35 | 0.365 |

| [FeL2Cl] | 20 | 0.208 | 17 | 0.376 | 68 | 0.459 |

| Mn(Me2EBC)Cl2 [64] | 10 | 0.067 | 96 | 7.344 | 95 | 5.928 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoang, T.; Mondal, S.; Allen, M.B.; Garcia, L.; Krause, J.A.; Oliver, A.G.; Prior, T.J.; Hubin, T.J. Synthesis and Characterization of Late Transition Metal Complexes of Mono-Acetate Pendant Armed Ethylene Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocycles with Promise as Oxidation Catalysts for Dye Bleaching. Molecules 2023, 28, 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010232

Hoang T, Mondal S, Allen MB, Garcia L, Krause JA, Oliver AG, Prior TJ, Hubin TJ. Synthesis and Characterization of Late Transition Metal Complexes of Mono-Acetate Pendant Armed Ethylene Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocycles with Promise as Oxidation Catalysts for Dye Bleaching. Molecules. 2023; 28(1):232. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010232

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoang, Tuyet, Somrita Mondal, Michael B. Allen, Leslie Garcia, Jeanette A. Krause, Allen G. Oliver, Timothy J. Prior, and Timothy J. Hubin. 2023. "Synthesis and Characterization of Late Transition Metal Complexes of Mono-Acetate Pendant Armed Ethylene Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocycles with Promise as Oxidation Catalysts for Dye Bleaching" Molecules 28, no. 1: 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010232